By Jeremy Caniglia

jeremycaniglia.com

Mimesis — the copying of a masterwork — has been a key part of painters’ training since classical antiquity. As musicians must learn basic instrumental techniques before developing their own styles, so artists can learn a great deal from perfecting a past master’s technical elements. Painters such as Leonardo, Michelangelo, Velázquez, Rubens, and Rembrandt all created master copies throughout their lives.

In 2018, I embarked on a four-year journey to paint a copy of “David with the Head of Goliath,” which was created by Michelangelo Merisi da Caravaggio (1571–1610) and is today always on view at Rome’s Galleria Borghese. I was determined to make my copy as close as possible to the original, from technique to scale to materials. My effort to get into the master’s head has given me insight into my own decisions and thought process and has opened my eyes to some of what Caravaggio might have contemplated.

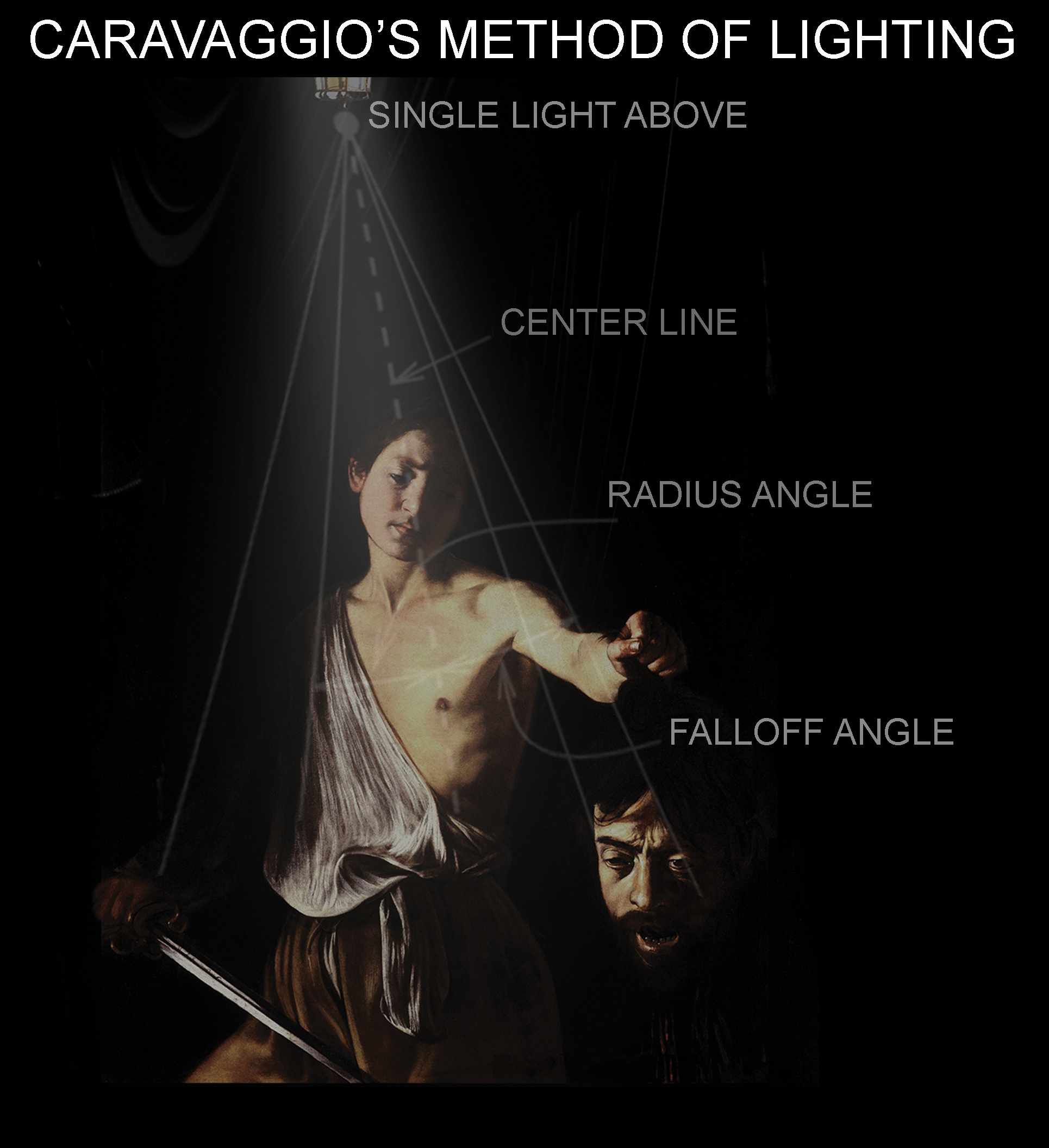

Caravaggio produced an extraordinary number of great works during his all-too-brief career. His method was meticulous, but also concise and utilitarian, allowing him to paint compositions as large as 13 by 10 feet in just a few months. I began by making two visits to Italy to study Caravaggio’s greatest works in Rome, Naples, and Sicily — to view them from all sides and to fully appreciate their brushwork, grounds, colors, and pentimenti, as well as how he made use of light. Before traveling, I read every possible book and academic article, which helped me gain appreciation for his mental state during his first stay in Naples (1606–07) when a growing body of evidence suggests he painted “David.”

Technical Research

During my studies, I consulted close-up photos provided by the Galleria Borghese. Technical analyses of Caravaggio’s paintings have been undertaken for decades, but particularly valuable to me was scholar Marco Cardinali’s research, including surface and cross-sectional X-ray radiography, X-ray fluorescence, and infrared reflectography. He has established the type of wooden stretchers Caravaggio used, size and weave of his canvases, earthen pigments available wherever he was living, and mediums.

My first step was to choose a wooden support accurate to Caravaggio’s time, and ultimately I opted for a kiln-dried, knot-free pine. The master painted on plain-weave canvas with a low thread count, and the closest match I could find was a Claessens unprimed Belgian woven linen canvas, which I stretched and secured on the back of the strainer with staples. (Caravaggio used tack nails.) Taking my lead from Cardinali’s research, I applied a thin ground layer of gesso (Italian for gypsum) — a dry mix of calcite and rabbit skin glue with warm water that is combined to form a gel. Once that chalky layer dried, I added a thin layer of Rublev Lead Oil Ground, which took a week to dry.

For the first ground layer, I mixed various powders, pigments, and walnut oil to create a thick, pliable plaster, akin to buttery taffy. It took two weeks to dry, and it was probably during that first week — as this earthen background layer stiffened — that Caravaggio began incising it with a form of chalk calcite or vine charcoal, mapping his figure positions while consulting his life models. Caravaggio was a superb draftsman and learned compositional drawing from his master Simone Peterzano, himself a student of Titian.

These etched lines were his starting guide and could be changed easily. The incised lines on the original at the Borghese are rather short and can be found on the profile of David’s neck and along the foreshortened left arm that holds Goliath’s head. Caravaggio then covered his lines with broad black brushstrokes — a fast way to build up the under-drawing in just a few sessions. This means his original drawing was covered up, so we generally rely on his unfinished paintings to better understand how those lines looked.

Continue reading in Fine Art Connoisseur magazine, September/October 2023…

Browse more articles on figurative art and artists here at RealismToday.com.