On AI Art generators > Contemporary artist Anthony Waichulis addresses the nature of art and the potential impact of AI technology.

AI Art Generators and the Art Experience

by Anthony Waichulis

anthonywaichulis.com

In 1883, a magazine called The Chautauqua posed the question, “If a tree were to fall on an island where there were no human beings, would there be any sound?” Thoughtfully, the publishers included an answer. It read, “No. Sound is the sensation excited in the ear when the air or other medium is set in motion.” A year later, Scientific American would address a slightly tweaked version of the question, which read, “If a tree were to fall on an uninhabited island, would there be any sound?” They, too, put forward an answer that corroborated the good folks at The Chautauqua. It read, “Sound is vibration, transmitted to our senses through the mechanism of the ear, and recognized as sound only at our nerve centers. The falling of the tree or any other disturbance will produce vibration of the air. If there be no ears to hear, there will be no sound.”

Yet today, many intuitively answer “yes” to this question. One reason for this is that many define “sound” as simply the vibration itself—a simplification that is likely reinforced by an affinity for utility in our day-to-day lives. Unfortunately, while simplifications like this can be advantageous in many contexts, they can become quite problematic in others. In this article, I am going to explain a bit about the nature of art and the potential impact that technology like AI Art Generators might have on it. But to navigate the issues properly, we must distinguish between the sound and the vibrations. We will need to acknowledge that, like sound—color, images, and even art are NOT properties of the environment. They are experiences found within us.

In our day-to-day lives, it seems perfectly reasonable to identify a drawing or painting on the wall as “a piece of art.” And in at least one sense, the statement is technically correct in that such an object contributes to the art experience in the same way that the vibration from the falling tree contributes to the experience of sound. In no uncertain terms, what we understand as art is no more a property of an object than “red” is of a Liberty apple. This is not to say that our regular assignments of great value to art objects are absurd. It is quite the opposite, as these objects facilitate or elicit a valued art experience. In other words, they are part of a highly valued “pleasure technology.”

Examining the nature of art through this lens, we can temporarily view art objects as metaphorical pieces of software that initiate potent “neural programs.” The perceived intrinsic properties (physical features) of the art object (software) combine with extrinsic properties (beliefs, biases, etc.) from an observer (hardware) to produce an experience that we describe as art. The potential combinations of these vital components are incredibly vast, with interactions occurring in many complex and fascinating ways. For example, we can encounter an art object that we may feel is lacking in certain typically attractive features, yet our beliefs about provenance, originality, or the artist’s virtuosity might significantly elevate the experience to something we might describe as incredibly beautiful.

So where does actual technology fit into this, and how might it impact our art experience? Well, one of the most significant extrinsic factors comes from our beliefs about the artist’s performance (e.g., how the object was created and the difficulty involved.) The greater the perceived difficulty, the more likely we are to assign high value to the endeavor.

Think about the last time you saw a drawing or painting that you initially felt was mediocre, only to learn that the artists overcame some significant difficulty to create it. Often, the information immediately alters your experience of the object. This is one of the reasons that you might see an artist stressing that they only work from life, use only hard-to-come-by or limited materials, avoid advantageous tools, etc., as such information impacts a viewer’s beliefs about performance. Unfortunately, our assumptions about difficulty can often be ill-informed, which can lead to some problematic biases, especially where the use of certain technologies is concerned.

One such technology of late is a family of computer programs called AI Art generators. Generally speaking, these generators are impressive computer programs that analyze massive amounts of data in specific ways to produce a range of “original” products that are similar in many ways to the source data. The most popular generators at present involve a text-to-image model. A text-to-image model is a machine learning model which takes as input a natural language description and produces an image that matches that description. (Unfortunately, much colloquial language is used in mainstream writings about these programs, which often anthropomorphizes and misrepresents the actual processes involved.)

So can the output of these programs truly be considered art objects? Absolutely. The intrinsic properties of the output can easily be seen as beautiful, eliciting a positive aesthetic response from an observer. However, AI products will always lose ground in the extrinsic properties category. You see, the one piece of art experience criteria that AI will never achieve is the extrinsic property of human virtuosity (i.e., demonstrable skill in contending with appreciated difficulty.). That’s right. No matter how beautiful the intrinsic output of an AI “image” is experienced to be or how well it can mimic the human creative process, it will never tick the extrinsic human performance box because it can never BE human.

But what about using AI art generators as a component or tool in our existing creative processes? (Perhaps as reference material for a drawing or painting?) Does that impact the art experience my work may elicit? Yes! Any perception of mechanical or technical advantage in one’s process will impact the assumptions about the difficulty and, thus, impact the perceived performance value. Some artists that I know are currently using generators to explore new ideas and options in the realm of design, pictorial composition, lighting scenarios, and color schemes. And even though their general process remains unchanged, awareness that AI output is involved in ANY way impacts perception and reception.

In addition, I have found that some of my peers object to the use of AI technology as they feel it may hamper the potential creativity of the artist. That argument, though, is highly problematic in the same way that claims of education killing creativity are nonsensical. Using AI generators to explore and grow ideas can, in one sense, be genuinely analogous to walking through a museum or even browsing images online to garner inspiration and discover new ideas (and many would likely not label such activities as responsible for killing creativity).

So should you use AI tools in your own creative process? In truth, there is no simple answer, as the landscape of artist goals and personal fulfillment is as diverse as it is vast. I would argue that if any tool can bring you closer to manifesting, in a fulfilling way, the type of art objects that you hope to create, and the experiences that you hope to elicit, then it is, at the very least, worth looking into. However, each creative needs to carefully consider the costs that any new tool will carry for the end user’s art experience.

In any case, I hope that some of the concepts presented here will help you make more informed, deliberate decisions for how your continued creative journey unfolds.

What are your thoughts on the use of AI for art? Share them with us in the comments below.

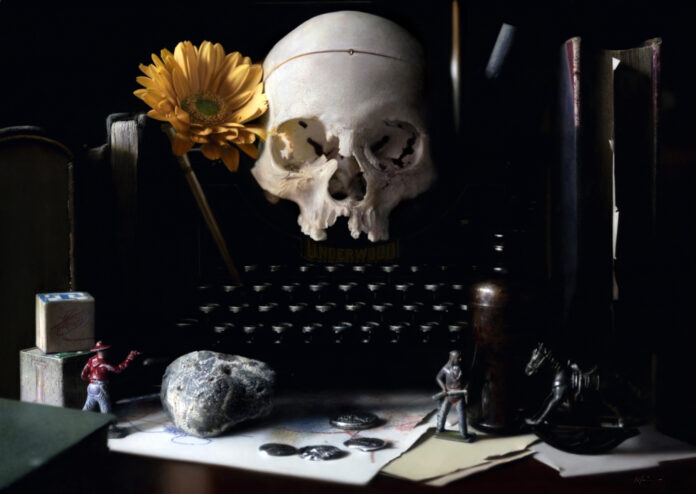

About the Author: Anthony Waichulis (b. 1972) is a contemporary Trompe L’Oeil painter from Northeast Pennsylvania. Often celebrated by critics and collectors alike, Waichulis’ efforts have captured top honors in both domestic and international competitions and have been published in most major art publications.

Take your realism art to the next level when you attend Realism Live ~ a multi-day virtual art conference led by 20+ world class artists. (No tech skills? No problem! If you can click a link, you can join our event!) Learn more at RealismLive.com!

Edited and prepared for the web by Cherie Dawn Haas, Editor of Realism Today

I think this is an excellent presentation concerning the pros and cons of an artist using AI image generators in his or her own work. I’ve been using DALL-E 2 as a learning tool in my effort to move from realistic oil painting to a much more Impressionistic style. I really didn’t know where to begin. So with prompts, I generated several images in the style I was interested in and then painted those images, the way I would have done had I used a photograph or setup for my painting’s source/reference.

After doing about 10 of these paintings, I felt that I had learned enough to begin painting from my own references (photos and shadow box set ups) to render them as Impressionist-style paintings.

Thus, in my case at least, using AI-generated images turned out to be a valuable learning tool.

Thank you, Martin! I am very glad to know that this new technology is useful for you in both your learning and creative process. I’ll be looking forward to seeing what comes off of your easel! <3

Mr. Waichulis, Thank you for giving me back some hope on the Fine Arts side. However, as a commercial artist for over 30 years, I don’t have a rosy outlook for the future of commercial artists. I’ve been around the block a few times, I’ve never worked at a company where an artist had the final say on any piece of art. There is always someone higher up the corporate food chain that has the final say, most of the time they are not artists nor do they have an art background. Artists and art departments already operate pretty much like all the AI image generators, we get a prompt/brief/request, generate some art for the boss to choose from, revise to their taste and so on. Once the bean counters see a bottom line savings by replacing artists with AI, it will happen. The value of commercial art is completely detached from how easy or difficult it was to create, only in how much revenue it can generate.

Greetings Jose! Thank you—you make great points, for sure. I’ve received a good bit of email about the impact of AI tools on the commercial end (and many are not rosy at this time, as you point out.) My writings and lectures on this subject have focused strictly on our assignments and experiences of art. In my experience, introducing impacts on job markets or corporate behaviors to that focus almost always leads to a good deal of conflation and confusion. I think it would be a good idea to author an insightful piece from a commercial artist’s point of view. I, for one, would be very interested to read it!!!

The truth is, though, this isn’t strictly about art. AI models are here to stay, and they will, inevitably, destabilize most industries to a shocking extent. This is till early days, but models like ChatGPT have already displayed such an unprecedented level of competence and capability that one can only imagine what the next 5-10 years will bring to the table in this realm.

In the first place, automation was always the fear of the common worker. And automation is still an ever present concern, but when you couple machine automation with a pseudo-AI running most of the processes, you have very few positions left to fill with a human, outside of contingency positions, oversight, maintenance, etc.

I do believe that unemployment will globally skyrocket within the next 10-20 years. And at some point in time, most people will be born with little to no professional prospects, because, you wouldn’t hire humans if you could already run 99% of the operation with machines and algorithms that don’t require payments, breaks, rights, etc etc.

Is it a dystopian future? Maybe. Maybe not. Time will tell, but I am confident that this is an inevitability that we’re heading towards with every technological advancement.

Today artists’ careers are in potential peril. But tomorrow, it’s literally everyone’s career.

Yes, new technologies can have a massive impact on society—and the topics you introduce are definitely worthy of discussion. However, we can often find more productive discourse if we limit our focus to avoid conflations that can make the issue at hand far more difficult to navigate. My focus here was simply to open up some of our colloquial concepts so as to potentially better understand and appreciate the role of AI imagery in the human art experience.

Comments are closed.