Contemporary Realism > I find that the more I’m burdened with the technical aspects of painting, the less I see. So before I lay my first brushstroke, I have to clear my mind so I can paint from the heart.

Contemporary Realism Art: The Emotional Painter in Me

by Ron Hicks

One of the only ways I have found to get to that emotional painter inside is to strive to have a solid understanding of all visual elements and approaches, to the point where this understanding is second nature. When I don’t have to think, then and only then am I able to paint intuitively, thus giving a pathway for the inner man to speak.

Thinking back to one of my first live painting classes fresh out of high school, I recall listening intently to my painting instructor speaking about what was set before me. His words were inspiring and at the same time very foreign to me.

Sitting before me in a rickety old chair, wearing a red and black kimono, was a model with what I can now describe as a pensive look about her. There was something great there, but I just didn’t know it! In my mind, I can still hear the instructor walking behind me urging the class to “paint what you see and feel.” At the time, I had not a clue what he was talking about. With my limited understanding, I could not connect the physical act of painting with a feeling or an emotion.

During that same period, I had an airbrush painting class. Like many students, I was consumed with the highly polished, almost photo-realistic finish you could achieve with an airbrush. I remember thinking, “If you could paint something exactly as it appears, transferring what you see visually to a two-dimensional surface, then you are a great artist.” So, proudly, I brought one of my finished airbrush pieces to my painting instructor. I’ll never forget—it was a painting of Tinker Bell spreading magic dust! He looked at it stoically and said, “This is irrelevant, you’re a painter.”

I was puzzled by his response, mainly because I naively thought it was the world’s greatest piece of art! I said to myself (rebelliously), “What does he know?” But I didn’t stop thinking about his comment, and later that year I began to truly understand what he was talking about. I started to look at my painting not only as a way to transfer information but also as a way to express an idea or make a statement.

A musician starts by learning scales and theory, but the connection to “music” is not always clear at first. Eventually, however, that music student graduates to playing proficiently and may move to composing and playing intuitively, expressing his interpretation of a particular piece.

Having the same dialog as an artist also requires a thorough, intimate understanding of your craft. I spent years doing countless paintings and studies of value, some of which will never see the light of day. These were all done in an effort to better understand value. It’s not enough to just transfer information. I believe you have to say something “about” or “with” the information you transfer through your art. Perhaps this will be easier to understand if I share some of the thoughts I have as I’m painting.

The old adage, expressed in different ways, is still true: “If you try to say something about everything, you will say nothing.” I keep this thought close to heart as I start a painting. Instead of jumping in and making ill-advised decisions, I first ask myself, “What is this painting about? How will I approach it visually?” Is it about light and shadow like Rembrandt’s “Agatha Bas” (1641)? In this piece, Rembrandt paints the light and its movement on the figure using seven or eight points of light and shadow. Or is my piece going to be more tonal like Degas’ “Racehorses at Longchamp” (1873-75)? Here the painting seems to be more about the relationship of shapes and their tones—value plus hue. The list could go on and on but ultimately I need to be clear in my mind about these factors before moving forward with a painting.

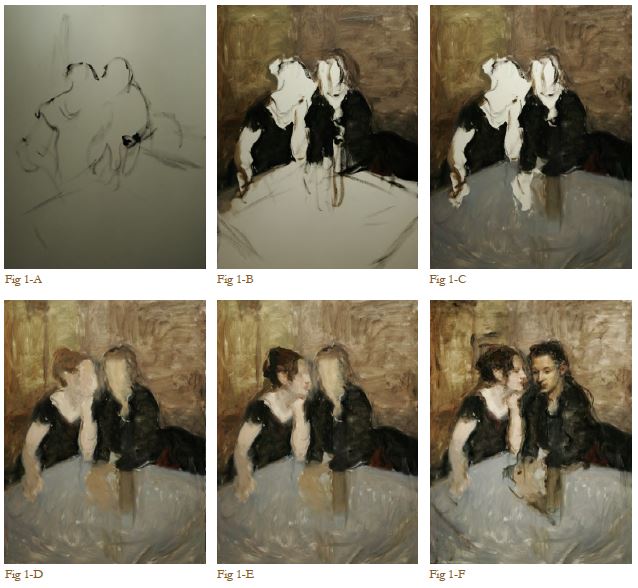

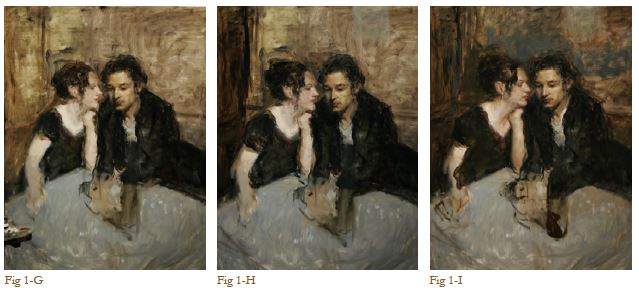

As a side thought I must add that beneath most good paintings there is a strong sense of shape and value. If you consider all of the visual elements (the ways to approach your painting visually)—shape, value, color, edges, texture, and line—I personally believe shape and value are most important. Regardless of what direction my paintings take, relative shape and value remain consistent (Fig 1-D).

Once I’ve gathered my thoughts on the visual approach I turn my attention to answering the question, “What do I want to say about the visual approach?” Keep in mind you could paint the same subject matter a hundred times and come up with something different to say each time. So I ask myself, “Is what I have before me primarily about the mood, or the light, or an emotion . . . or something else?”

Once I’ve addressed these questions, I tend to start my paintings abstractly—blocking or massing in the large masses directly to canvas (Fig 1-B), with not much in the way of a preliminary drawing. I prefer a mixture of Van Dyke brown and black or muted tones similar to the color and value I see in the composition.

As a young artist, my tendency was to get a likeness and accuracy of shape, living for the moment in the area I was working. I didn’t pay attention to how that area related to the rest of the painting. What I ended up with was what I like to call a spot painting—a lot of areas that were painted well but that did not contribute to the composition as a cohesive whole. With a few years of discovery under my belt I became more interested in the movement as a whole. I started to see more clearly the delicate balance and relationship of value, shape, edges, and color, especially as it related to the direction I was headed. This helped me to stay loose (in my painting and in my approach) and only commit when I was absolutely sure I wanted to.

I have a simpler approach to composition. For me, it’s easier to see a composition in its bigness as the sum of larger movements. Rather than seeing what is set before me as objects, I see them more as shapes in relation to one another, containing value, shape, etc. I can then see patterns of masses of light, medium and dark shapes. Using some basic design principles, I try to achieve maximum variety in the relationships of these masses. For example, I may see dominance in the medium masses, sub-dominance in the darks, and light masses that are more of an accent. This could make for an interesting composition, again, as long as there is variety. I try to make sure all of the shapes are not too similar in size, value, shape, color, and edges.

It’s my belief that if the composition works well in the large and simple masses it should stay the same no matter how you break it down, as long as you keep the relationships of the masses consistent. In other words, it is my contention that the basic structure of a painting is the same. Whether the painting consists of a few large abstract shapes, or if those large abstract shapes are broken down into thousands of brushstrokes, they are still relative. The only thing that will change is how one receives or perceives the information you’ve set before them. If the breakdown of your painting is more representational, it may be perceived differently than a non-objective painting.

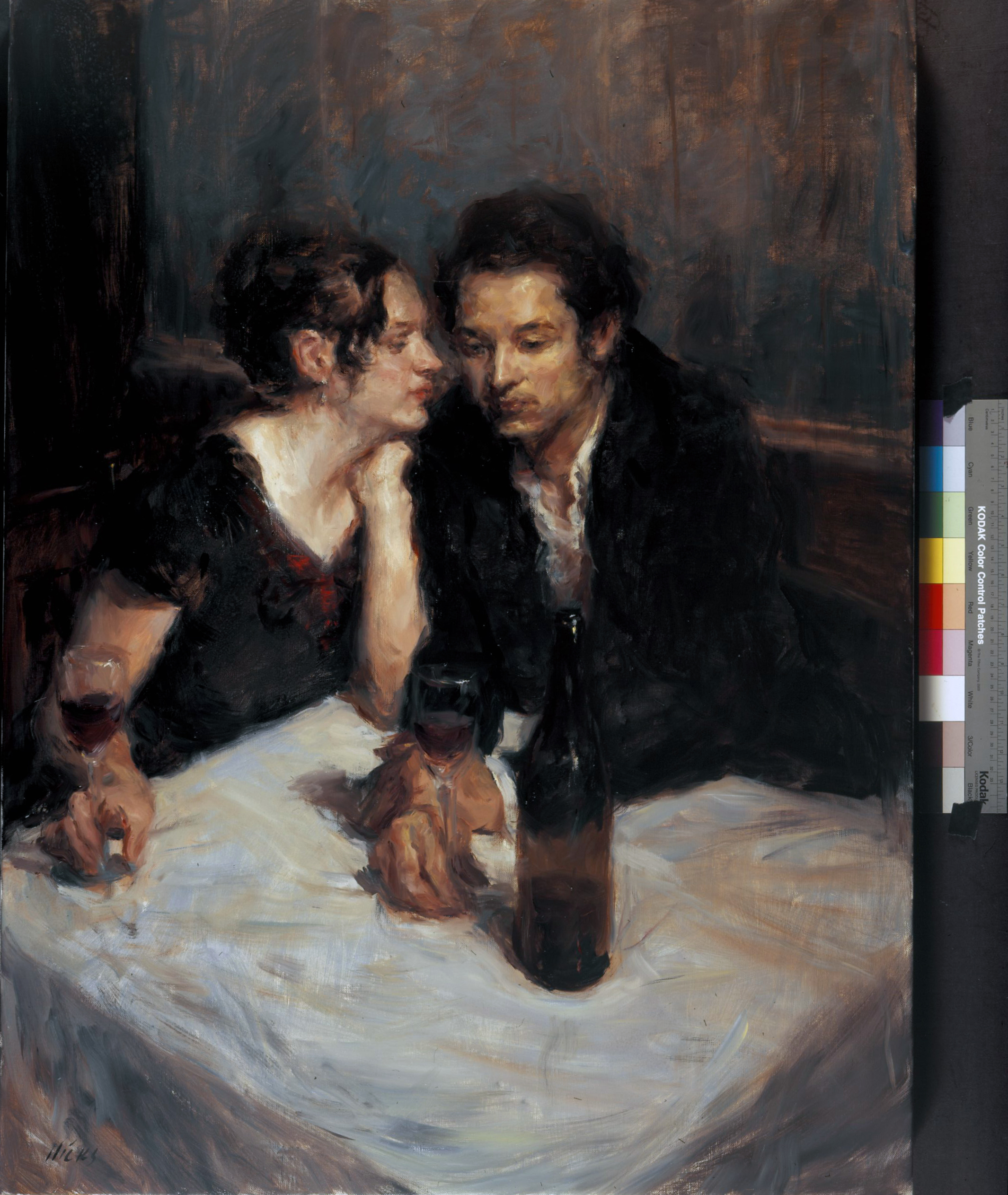

Generally, the rest of my time with the painting is spent getting lost in it (Figs 1-E to 1-J), playing with the large relationships or movements, and paying close attention to what my primary vision for the piece is. This is not to say that once I have an idea it is etched in stone and doesn’t change. If I am moved in a certain direction, I go in that direction. Because I have somewhat freed myself from technical considerations, I am able to follow my heart and rely more on my intuition while painting.

The French novelist Andre Gide said: “Art is a collaboration between God and the artist, and the less the artist does the better.” I use all of the visual elements at hand to achieve balance and harmony in a piece, trying to create one corporate movement that speaks emotively to the viewer, rather than highlighting how technically proficient the work is.

My goal is to share my vision. My hope is that whoever views my work will have their own intimate encounter with it. I consider myself simply the vehicle used to deliver the work to them.

- Visit PaintTube.tv to learn how to paint portraits and figures in the style of contemporary realism, and much more.

- Join us for the next annual Realism Live virtual art conference and study with the world’s best contemporary realism artists.