Too many artists are caught in drawing from life as a one-way street towards surface description. Here’s a look at the complexity of life drawing.

BY EMIL ROBINSON

(Originally published in Artists on Art magazine, Summer 2014)

I consider life drawing to be a vital part of my artistic practice. I have been drawing and painting from the model weekly since 2007. In that time I have seen many different “methods” and I think that there is a wrong turn that many realist artists have taken today in their teaching and practice of life drawing.

First, there is no substitute for the copying of master drawings to learn how to draw the figure. Drawing is a language separate from but connected to nature. Too many artists are caught in drawing from life as a one-way street towards surface description. It is just as important to look at and copy wonderful art of the past to unlock the language of drawing.

This language is much more complex and powerful than accurate and specific rendering. Many atelier style schools of learning that espouse old master skill building have sprung up around the world. Although these programs have a noble sense of history and the power of tradition, they do a poor job creating meaningful figurative artists.

The great masters of the past did not work hours and hours on each drawing focused on the perfect rendering of surface. Anatomy and sculpture drawing were practiced exhaustively, but drawing was seen as a rapid and powerful tool of formal and emotional communication. Rendering was a way of unifying and celebrating the power of a drawing’s design, and its place within a composition. Many great works were beautifully polished, but they breathe with a life force born of a more vital set of goals.

The great master drawings convince me because of the beauty of their wholeness, not because of the clarity and correctness of their separate anatomical parts. In this article I have tried to write down a set of priorities that I see in the work of the great draftsmen.

1. Empathy is imperative: Michelangelo, “Study for Lamentation” (1530)

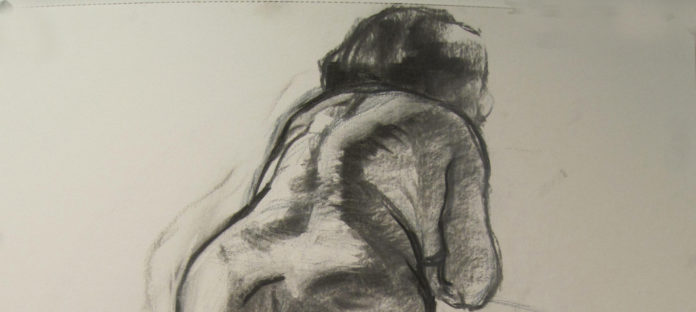

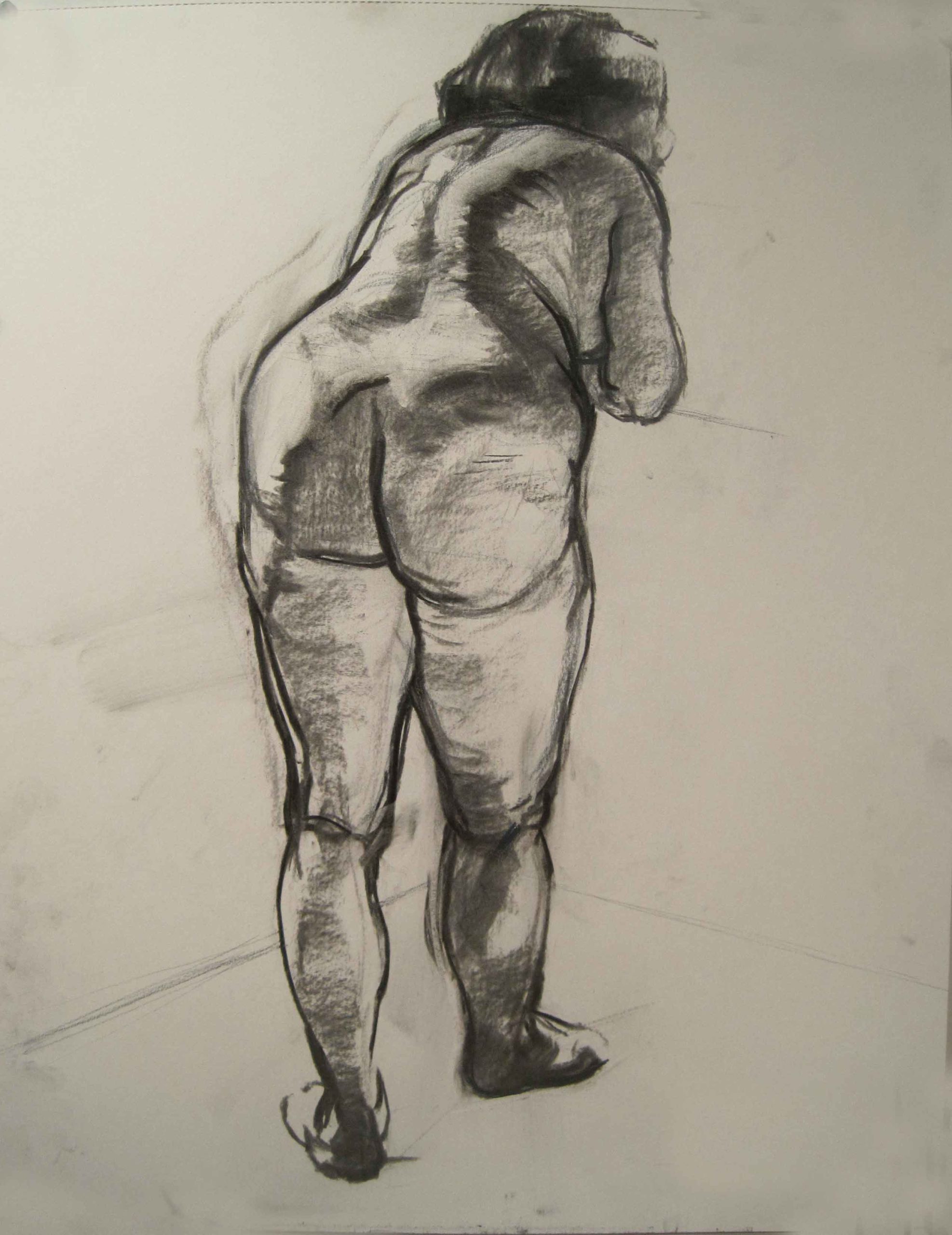

The drawing starts with the artist’s ability to empathize with the figure they are drawing. The artist approaches life drawing feeling connected to, if not the same as, the figures being depicted. A premium is placed on physical empathy: the weight, posture and forces in the body. This empathy creates a space of intimacy between the artist and model and artist and drawing. The drawing is a celebration of this intimacy. Eros is palpable in a drawing done in this spirit.

2. The focus is on the drawing’s needs, not the needs of correct anatomy or illusion: Käthe Kollwitz, “Mother and Dead Child” (1903)

The physical marks that make the drawing are concerned with finding an inventive drawing solution to the pictorial and psychological concerns of the artist. These concerns always run counter to the desire to render each moment of the body with bland, even attention. Invention and personality are what separate purely skillful studies from inspired works of art. In the Kollwitz drawing nothing important to her vision has been left out, and there is a sense of organic flux to the level of finish.

Light and dark red chalk, Staatliche Graphische Sammlung Münich

3. Gesture as philosophy, not separate exercise: Jacopo Pontormo, “Two Standing Women”

Concentration and trust need to advance in tandem for an artist to draw with authority. Gesture drawing is taught today as a quick exercise to loosen the artist up for more serious drawing. I believe gesture drawing, or drawing with energy and purpose through the whole form, to discover its rhythms, mass, and posture, is the way an artist should approach the whole drawing experience, whether it is a one-minute drawing or a drawing over the span of weeks.

In a longer drawing the artist tries to reconcile greater subtlety and detail with the power of the overall design and unity of form found in the gestural spirit. Drawing a difficult spatial or anatomical moment is much more manageable when the artist is moving freely and approaches the trouble spot with the confidence and goal of moving through the whole body organically.

A hand is not the hand in an anatomy book; it is a particular shape and character appropriate for its voice within the design of the drawing in response to the pose and needs of the picture.

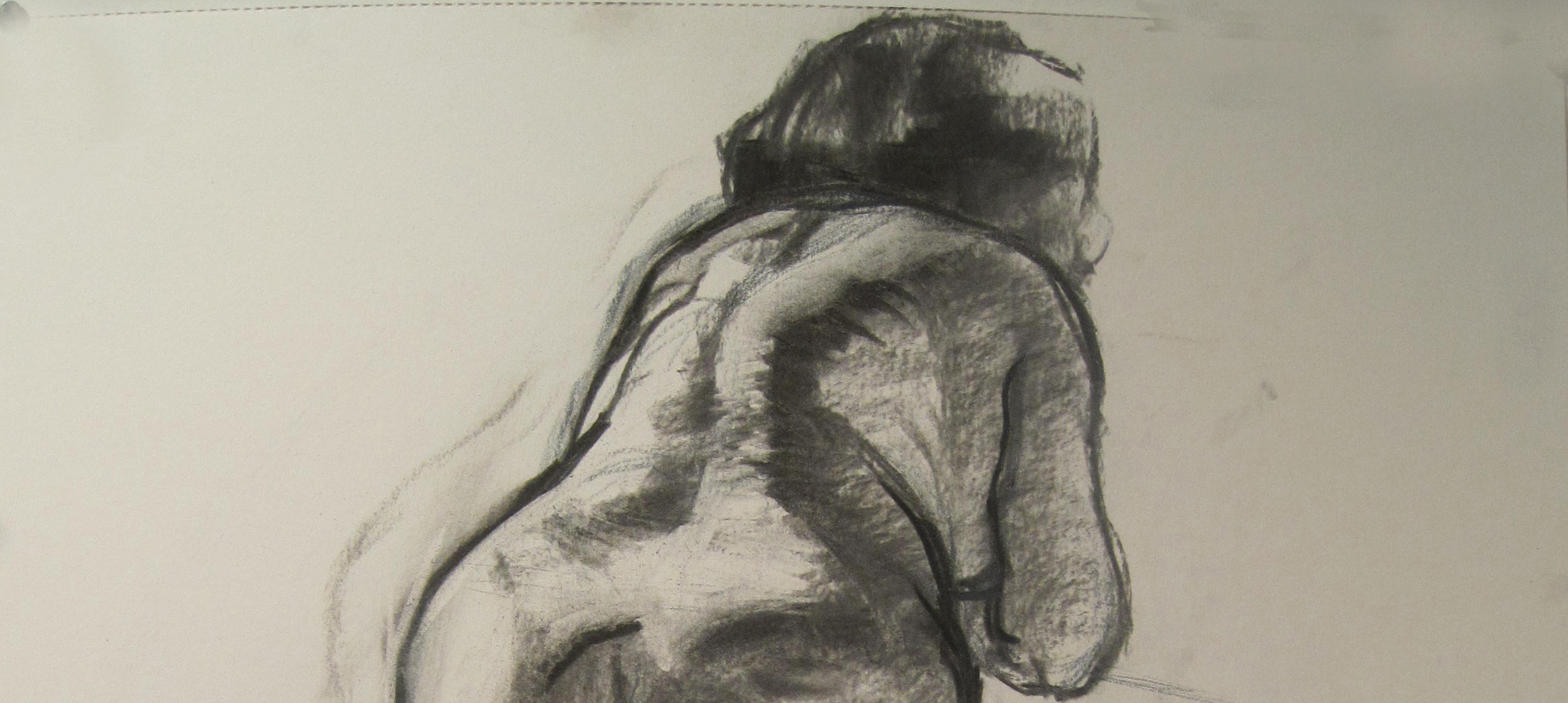

4. Line and shading as one generative system: Tintoretto, “Studies for St. Sebastian”

The artists of the past drew with line in such a way that those lines moved through the body, sparking a form that appears knit together. This means that each anatomical mass of the body is built through multiple lines that create the most graceful and taut connection to the rest of the model’s body.

The lines construct and build the form instead of just tracing the exterior envelope of contour space. Every form has its own logic and gesture that contributes to the logic and gesture of the whole. The line easily transitions into shading because of the intelligence of the line’s journey. The lines in the Tintoretto drawing always are at the service of form, weight and anatomy.

There are no useless lines or lines that do not contribute to the power of the figure. These lines double as shading because they build structural integrity and also promote the flow of energy through the drawing. Lines that keep these priorities in a figure drawing will inevitably lead to sophisticated masses of light and shadow.

Learn more about Emil at: www.emilrobinson.com

> Visit EricRhoads.com (Publisher of Realism Today) to learn about opportunities for artists and art collectors, including:

- Art retreats

- International art trips

- Art conventions

- Art workshops (in person and online)

- And more!