Hyperrealism Art > “The single moment captured in one second in the photography is being transferred for months to the canvas to make this moment eternal,” says Jan Mikulka. “The obsession in those moments…excites me even more when I am making the painting.”

To Make a Single Moment Eternal

BY JAN MIKULKA

Contact: [email protected]

On first sight my paintings might look like photographs, but I am always trying, like many painters of hyperrealism, to embrace the depth in my works of art. The technique of old masters, which I am using in my paintings, enables me to create this depth, even though a photograph is usually the model for a certain picture. I am always trying to go beyond the flatness of the photograph by emphasizing a psychological dimension of the picture. I don’t want to capture just the shallow appearance of my model, even though some viewers are satisfied just with this representation of the figure or the thing.

In my work I am going further by revealing the identity and personality of every single model. I am going far beyond the photography, which is usually my model, and emphasizing the psychological moment of the image, which differentiates me from photo-realist artists, with whom I have often been compared. I am definitely not trying to make some cool formalization of what I see; I rather reveal the physical individuality of a particular person in every detail of his or her individual form. This searching for human uniqueness has been brought up in my works to the level of painful naturalism.

Larger Than Life

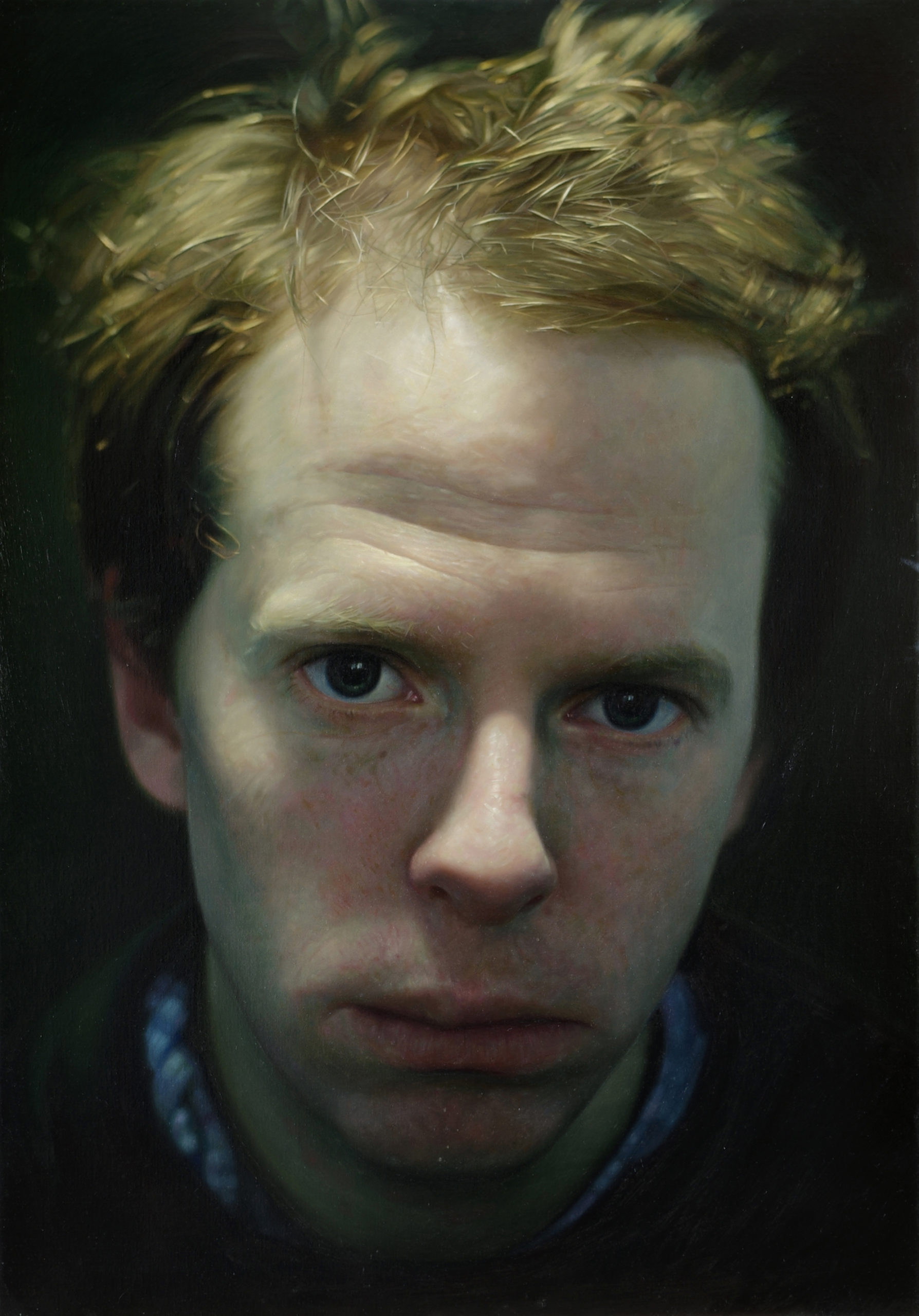

The larger-than-life portraits are the ideal form to examine this approach. In this context I would like to mention the portrait of my friend Jakub—my friend from childhood. Because I have known him for so long and I have done several large-scale portraits of him, it was a while before I could focus more on the psychology of his image.

At the same time Jakub has a very specific look—pale skin with freckles. It was a kind of painterly challenge to paint him from a short distance, and it gave me opportunity to experiment with a range of light effects in Jakub’s hair and skin tones. To paint someone I have known for so long might seem easier than to paint someone you have never seen before, but that’s definitely not true.

During the work on Jakub’s portrait it often seemed to me like a re-examination of our whole relationship. This is obvious given time I spent with Jakub doing the portrait (more exactly with the photograph of Jakub)—several hours every day for three months.

If working on Jakub’s portrait was a re-examination of our relationship, working on “Self Portrait” was like a struggle with myself: spending hours, weeks and months working on my self portrait I asked myself so many existential questions—the types of questions we are usually trying to forget about and avoid in our everyday lives. I was very glad afterwards, that the jury of the prestigious Portrait Awards of the British Portrait Gallery awarded my self portrait a first prize in the competition of 1,000 portraits from of all around the world.

What made my portrait different from the others? Well-known American painter Phil Hale, currently living in London, was one of the jury members, and he recently described the sense of humanity, which he found in my self portrait, this psychological depth I mentioned earlier.

Winning first prize at this competition was a really great satisfaction for me and also a proof of a meaningfulness of my work. Even though hyperrealism and photorealism are quite familiar to the art world today, returning back to the old master technique sometimes seem like a reactionary act for someone, but for me it’s just a way that suits me the best to express what I want to picture.

When I am working on a large-scale portrait I usually use this procedure: I draw the outline of the face on the canvas, then make an acrylic underpainting and define the basic shadows. Afterwards I continue with oil paints, creating the classic oil painting. For large-scale paintings it takes me an average of a week to make an acrylic base paint and three months to do the oil painting.

Except the portraits and self portraits I am also working on figurative paintings. In the picture “Vana – Bathtub,” I had been researching the contact of the human body and the water. The reflection of the surface of the water can add (as a mirroring effect) a new dimension to the picture.

In this particular picture I focused on atmosphere—the subtle color composition of turquoise, purple and white, emphasizing the model’s pale skin. The lighting of the scene was developed from the side of the viewer and it fades towards the center of the image.

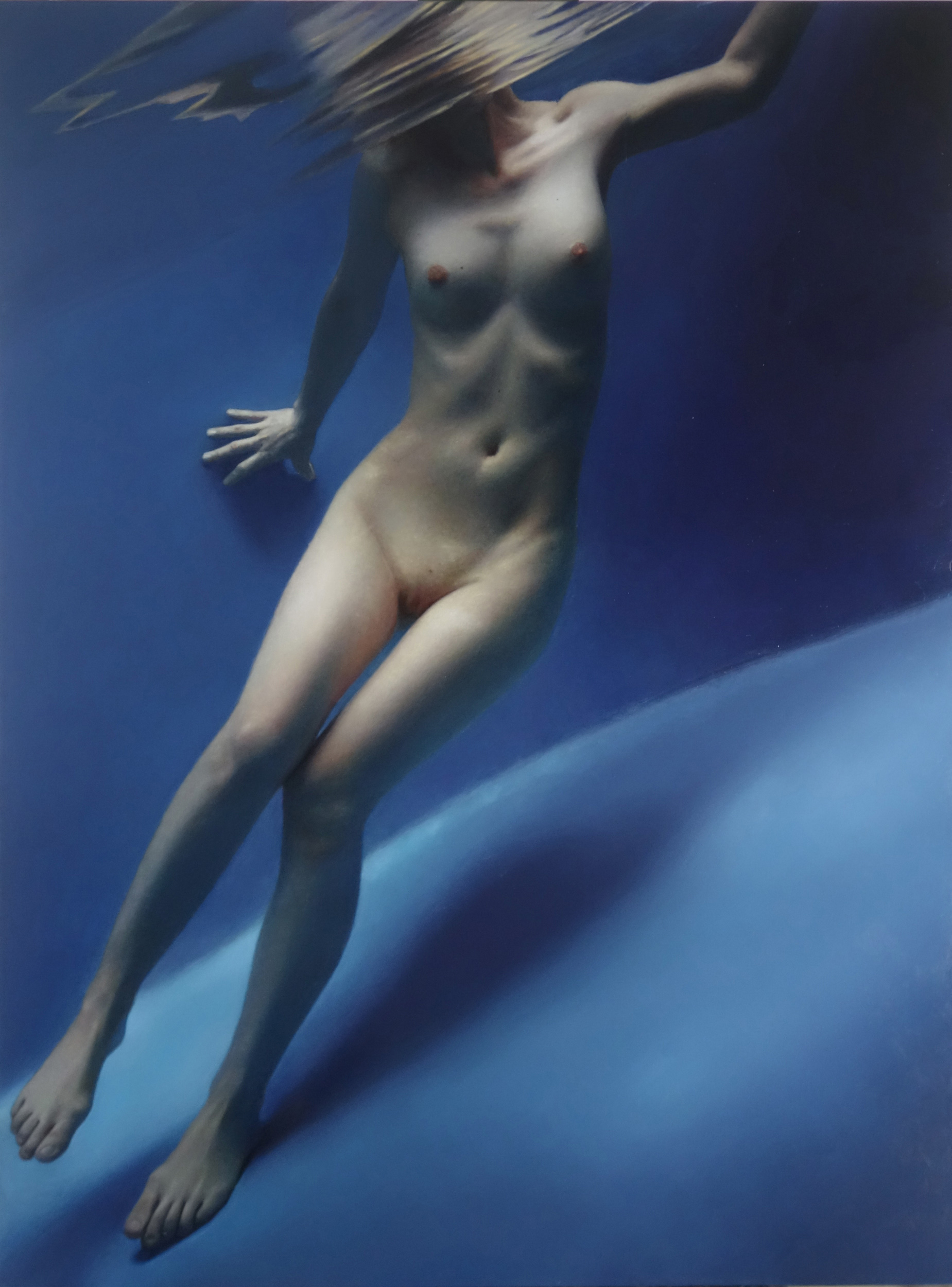

Water and the female figure were essentials also for the picture “Akt v modré (Act in Blue)”. The light dispersed in the water, the unique formation of molecules, which will never happen again in the same form. Not just in this painting, where I emphasized the atmospheric effects of water reflections, but in all my works I am—thanks to the photography—capturing the unique moments of our lives—this very now, which will never be repeated in the same way.

The obsession in those moments, when I am capturing the photograph, excites me even more when I am making the painting. The single moment captured in one second in the photography is being transferred for months to the canvas to make this moment eternal.

This can be seen, for example, in the painting “Šipka,” where we see a girl jumping into a lake.

The motif comes from random summer photos I took using my phone. I liked the scene so much I had to turn it into the painting, even though it wasn’t a good quality photograph and I had to make up some details of the picture.

This work also prefigured my newest series of paintings of the figure in nature.

Additional Hyperrealism Paintings by Jan Mikulka

In Pursuit of the Real:

Painting and Percept in the Works of Jan Mikulka

(an excerpt from the 2019 exhibition catalogue for the Cermak Eisenkraft gallery)

BY MARK GISBOURNE

As a painter of realism, Mikulka addresses the distinction between the “real” and reality of things in the world. The psychical state of presence is always real since we are alive. It follows that our inner state consciousness and presence to ourselves is always available and that the primordial real or inner self have no absence. The argument loosely follows the Lacanian model.

In order to communicate and convey meaning we have necessarily to use spoken or visual forms of representation. In a painting practice that uses realism the representational absence is realized through the imaginary real and the connotative symbolic unconscious stemming from immediate figurative depictions of the reality of things in the world.

In the case of Mikulka this argument is foregrounded against ideas that suggest he simply copies the contents photographs, and that his paintings are a form of imitative photorealism. Milkulka’s use of realism for the purposes of representation it is therefore aimed at the subtle aspects that lie hidden in mimesis, not so much copying what is seen but as trying too embody or using Heideggarian term of aletheia “un-conceal” the absent presence and sense of the real.

His use of portraiture reveals the founding aspect of subjective personal identity formed is that of a portrait or visual identity of the other that is usually our mother. Hence the question of self and other is substantiated and when cast in the context and established gaze of an artist-portrait painter, the question of engaged self-fashioning between the viewer and the viewed is discussed; first is relation to self-portraiture, and thereafter in relation to the sitter as the subject self and the object-sitter. It is verified that unlike other genre the viewed object will always necessarily have existed in the world, since portraiture is always implicated in issues of identity and recognition.

In still life it is argued that Mikulka’s perception and use of composition and projected space differs from that of a photograph. The subtle sense of spatial composition and control is perceived as commensurate more with the eye and the sensory stimulus of visual experience rather than as the mechanical registration of the camera. A visual analysis of the space followed to this effect. Still life is placed in context of origin and subsequent mastery as an established autonomous genre in the seventeenth century, and the perception of spatial composition is compared and contrasted.

In the nude paintings Mikulka addresses another historical and classical genre established primarily in the modern age by the Renaissance. The “nude’ is contrasted with the concept of the “body’ that has replaced it as a subject in more recent times. The body emphasizes interiority and materiality, and the ideal nude emphasizes exteriority and the linearity of the confined body as subject. Further vindications are provided by art historical references to the traditional genre of painting the nude.

Browse more articles on hyperrealism and photorealism in art at RealismToday.com.

> Visit EricRhoads.com (Publisher of Realism Today) to learn about opportunities for artists and art collectors, including:

- Art retreats

- International art trips

- Art conventions on contemporary realism, including hyperrealism art

- Art workshops (in person and online)

- And more!