Making an Impression with Commissioned Portraits

By Brian Neher

www.BrianNeher.com

When it comes to painting commissioned portraits, an artist’s ability to capture the personality and character of his sitter could mean the difference between a good portrait and a great portrait. Great painters of the past such as John Singer Sargent, Anders Zorn, and Cecilia Beaux were able to tap into the viewer’s emotions, allowing them to feel as if they, too, had some connection to the person in the painting.

It’s this initial impression that I’m after when meeting someone for the first time. My goal is to try to capture that same spirit on canvas in a way that pleases the client, satisfies me as an artist, and that produces a painting that anyone would enjoy looking at.

Portraiture is not about merely recording facts in order to get a likeness but, more importantly, it’s about translating, editing, and interpreting those facts in order to bring out a sitter’s unique personality. This process often takes place by emphasizing or downplaying certain areas of a painting in order to help draw the viewer’s attention to a point of interest and help bring expression and life to a portrait. Harold Speed spoke of this subject in his book, The Practice and Science of Drawing, as he explained the differences between mechanical accuracy and artistic accuracy.

The study of human behavior and body language also plays an important role when trying to determine what pose would work best for a client. Even the most subtle gesture can speak volumes about someone’s attitude and character. How a person stands, sits, places their hands, or tilts their head all give outward clues about their inward personality. These mannerisms will also factor into whether the painting will be perceived by the viewer as either formal or informal.

In order to successfully capture someone’s character on canvas you must first be able to recognize it for yourself through the use of both observation and intuition. To achieve this, I prefer to spend some time with a client beforehand to talk about what they had in mind for the portrait in terms of size, location, and pose. These meetings have proven to be very helpful to me over the years, especially when the subject is a child. As I’m getting to know someone’s personality during the course of this meeting, I’m also beginning the mental process of filtering through all of the facts that are in front of me and boiling them down into a few key visual gestures that I think would most effectively convey that same personality to others. These mental images will later work their way onto canvas back in the studio when finalizing the details of the composition.

John Singer Sargent was a master at this editing process and could sum up his sitter’s character, emotions, and sense of accomplishment in a single image, creating a lasting impression in the viewer’s mind—much like the impression you have when meeting someone for the first time.

With this vital information, I’m better equipped when taking photos during the sitting, and I know what to look for in order to accurately portray the sitter’s character in the final portrait.

Painting Commissioned Portraits

Once I’ve captured the information that I need on camera, it’s then time to begin translating and interpreting those facts back in the studio. After deciding which photos to use, I’ll have them printed in black and white, usually 8 x 10-inch enlargements. I prefer to work from black and white photos because I find it easier to see and judge the correct value relationships (how one value compares to another when registered on a value scale from black to white). By using black and white photos I am also not relying on the color of a photo. Instead, black and white photos force me to incorporate my own color scheme—based on the knowledge of a simple color wheel and the use of complementary colors—in order to create warm and cool temperature changes.

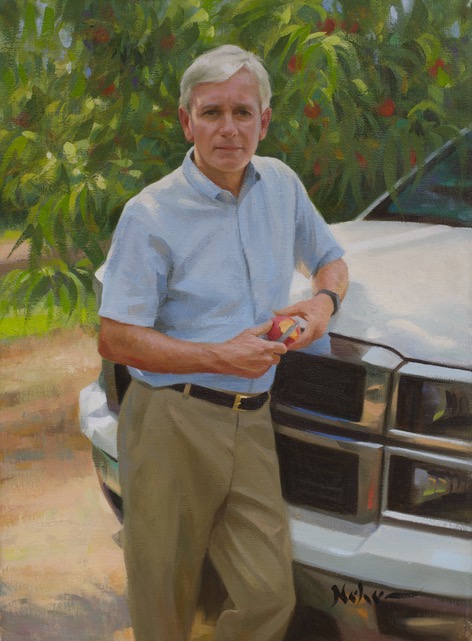

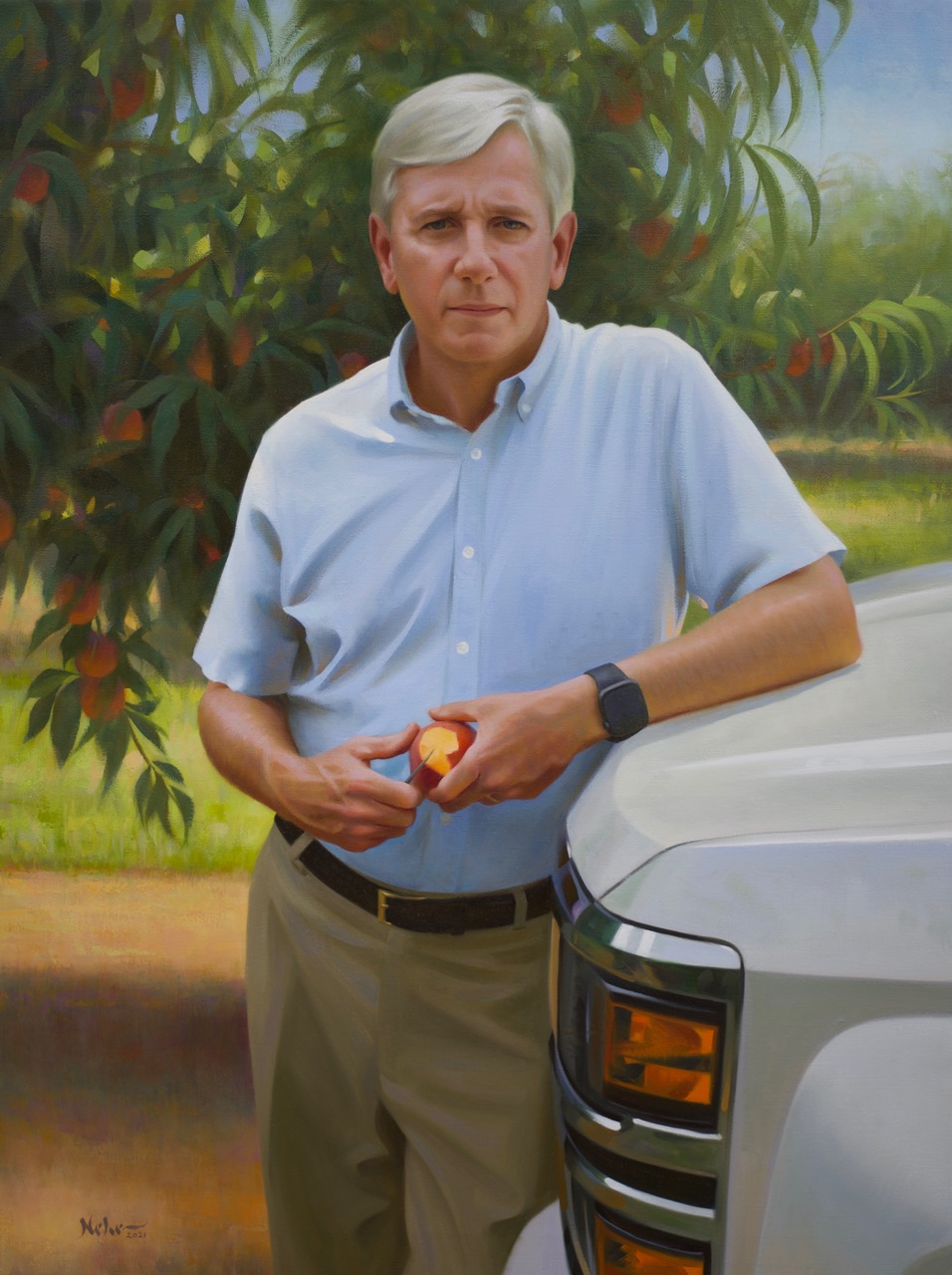

Before beginning any work on a final portrait, I like to begin by painting two small preliminary studies in oil (8 x 10 inches). These studies are presented to the client in order to give them a choice of preferred pose. These paintings also allow me to work out any problems in composition, value, and color beforehand and also provide me with a guide that I can use when painting the final portrait. This also gives the client a better idea of what I had in mind and allows them to see what the subject will look like in paint.

These studies have been a tremendous help to both me and my clients over the years and I’ve learned a great deal about painting as a result of doing them. If I run into a problem on the small study, chances are I’m going to run into the same problem—only on a larger scale—when painting the final portrait. It’s better to work out as many problems as possible at this stage. The studies also allow for the inclusion into the final portrait of any changes or suggestions that the client may have. Making these changes part of the painting process eliminates the need to go back and repaint certain areas of the final portrait in order to meet client expectations.

I was first introduced to the idea of painting preliminary studies by Joe Bowler, one of the great master portrait painters of our time. I highly recommend their use to other artists as well. Joe also got me started on painting portraits in outdoor settings and recommended I study the work of some great painters like Joaquin Sorolla and Frank Benson as examples.

These artists understood the importance of correct value relationships, in conjunction with warm and cool temperature changes within those values, in order to help create the illusion of outdoor light.

When starting a portrait, I like to mark off where the top and sides of the head will be, as well as the bottom of the chin. By doing so, I can then use this measurement as a reference point to determine how many heads high or wide the figure will be. From there, I’ll indicate the head with a simple but accurate drawing before blocking in a value for the background behind the head.

It’s important to determine what my darkest value will be and where it will occur in my painting so that I can place it on my canvas at the beginning stages. I then use this dark value as a reference point when judging other values. In order to accurately judge value relationships you must first establish a fixed reference point from which to judge all other values. For this painting demonstration, I’ve determined that the darkest values will be in the child’s eyes. Because of this, I now know that every other value in the painting will register higher on the value scale in order to preserve the correct value relationships.

Knowing relative value relationships is one thing, but sticking to it is a different story altogether. I can remember working on many paintings as an art student, only to change my darkest value halfway through. I then had to go back and make the painstaking corrections that were needed in order to get the correct value relationships. If you’ve ever found yourself in the same boat, you can reverse this course by constantly measuring all of your values next to this established dark value in order to keep the relationships correct. This is extremely important to know because value not only provides the means for creating the illusion of form but also sets the stage on which color performs. By maintaining the correct value relationships, you can then have the freedom to employ warm and cool temperature changes within those values in order to create the illusion of lifelike flesh tones.

Once I know where the head will be placed and I have some key values set down to use as guides, I then begin putting down large shapes of color that can later be fused together by using a combination of both a brush and my fingers. It’s also important to note that during this process of blending and softening edges, I am also drawing at the same time by adjusting those shapes as I go along. Once I am confident that I have enough information down and am off to a good start, I’ll then put the painting aside for a couple of days to allow the paint to dry. The paint during this first session provides me with a good surface on which to work and will also show through in certain areas of the painting at later stages, providing some nice temperature changes within the skin tones.

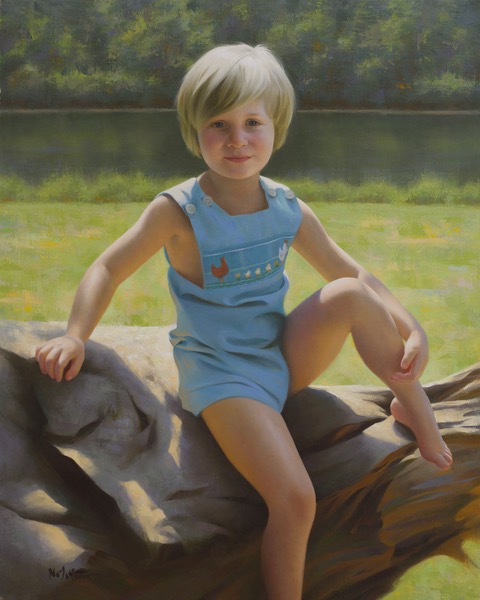

Painting Children’s Portraits: A Demo

When painting children, especially a baby as young as the one in the demonstration below, subtle shifts in color, value, and edges become extremely important in order to maintain the soft look and age of a child. These subtleties also begin to add up throughout the painting process, helping to reveal the child’s unique qualities and character. Finding a good balance in these areas takes time but is well worth the effort.

Speaking of balance, you’ll notice toward the end of the demonstration that I made quite a few changes to the background and clothing of the child. This is an example of trial and error in an effort to find the correct balance of values and color in the background that would help complement the child’s flesh tones. The purpose in reworking the clothing was to eliminate any unnecessary detail and to incorporate more lost edges in order to keep the focus on the child’s head.

The act of painting is not a perfect execution of one’s abilities, and changes like this are often necessary in order to achieve the end result. No matter how many mistakes you make when painting, what ultimately matters is that you determine to press on until you get the end result that you’re looking for. Thomas Eakins summed this up by nicely saying, “Painting is a series of mistakes and corrections.”

Once all of the adjustments have been made and I feel as though I’ve captured the child’s likeness and character, it then becomes a matter of knowing when to stop. This brings us to the age-old question: “When is a painting finished?” The answer is when there is nothing more that needs to be said. This sounds simple but often takes many years of painting in order to fully grasp and incorporate into your own practice. Believe me—I’ve ruined many paintings by not stopping when I should have, only to regret it later on.

Once the painting is complete, it is then delivered to the client for approval. Some clients prefer to have the original painting sent to them for approval while others may want me to email them a digital photo before shipping the original. In a situation like that, it’s important to have good, clear photos of your work that are ready to show to the client. This is their first impression of the painting, so be sure that it’s your very best. This photo can also be used to add to your portfolio as well.

One of the requirements of being a commissioned portrait painter is being willing to make changes if necessary. I’ve been fortunate over the years to have wonderful clients who have rarely asked for changes, and when they did it involved only minor adjustments. These changes may simply be to add more color in the eyes or a slight upturn in the corner of the mouth in order to help create a more pleasing smile.

Your willingness to make minor changes like this could lead to a repeat client, or even having them recommend you to all of their friends. Remember: you’re not only painting a product to sell but you are also building relationships. The experience that a client has when working with you is just as important as the portrait you paint for them. Each time they pause to look at their painting they will be reminded not only of their loved one but also of the experience that they had with you, the artist.

Making a good impression, both on and off canvas, will help to shape and fashion this first experience with a client into a work of art that they will remember for years to come.

Visit EricRhoads.com (Publisher of Realism Today) to learn about opportunities for artists and art collectors, including Art Retreats – International Art Trips – Art Conventions – Art Workshops (in person and online, including Realism Live) – And More!

Brian, thank you so much for writing this piece for us. Your information was enlightening, and a great resource for those of us that are studying portraiture.

Your work is wonderful, and truly shows the beauty, and wonder of the people that you are painting, what an honor to be able to record this for your fellow human beings.

Judith R.Legg

Comments are closed.