An article by William Schneider on painting, why it’s important for an artist to be a perpetual student, and eleven ways to do so.

BY WILLIAM SCHNEIDER

Why do some artists get to a certain level and then stagnate, while others keep improving their entire lives? I paint at the Palette and Chisel in Chicago; some of the members seem to make the same mistakes month after month . . . clearly “practice does not make perfect.” In fact, coaches have now amended that saying to “perfect practice makes perfect.”

On the other hand, some artists keep steadily climbing the ladder.

One of my workshop students was eager, but not very accomplished. When she took another workshop from me the following year, her skill level had jumped a hundred percent! She continued to study and learn and is now winning national competitions and launching a professional career. (By the way, she is not a young prodigy; she started on this path when her kids were out of school.) This topic is of particular interest to me because I went back to art school when I was in my 40s and had to pursue it on a part-time basis until only 10 years ago.

Here are a few actions that I have found helpful:

1. Set goals for yourself. I found that if I write down a few specific objectives (including a due date), I am much more likely to achieve them. I tape these to my bathroom mirror, where I see them morning and night. An example might be: “Design a large (40 x 60) multi-figure painting by April 1.”

2. Research (and analyze). I look at art books and go to museums frequently to try to figure out why some pieces work better than others; I think of “reverse engineering” them. My wife and I took a trip to Montréal (in February . . . brrrr) to see an exhibition of J. W. Waterhouse. I would walk three blocks from our hotel to the Musée des Beaux-Arts and study the masterworks. I’d return to the hotel, eat lunch with my wife, and then both of us would return to the museum for more study and analysis. Then we’d leave to eat supper and she would go to the spa or watch TV while I went back to the museum. I filled my sketchbook with drawings and notes. Where did Waterhouse place his key figures? What was the pattern of lights and darks? What was the overall color harmony? Was there an explicit narrative? I tried to imagine what he painted first, what was second, and so on. After three days of this, the light bulbs began to come on and I started to understand the logic to his compositions.

3. Copy masterworks. A century ago, when students completed their basic studies, they were sent off to copy masterworks at the Louvre or the Prado. I find that if I just study a masterpiece I can quickly forget the lessons learned. But if I copy the painting, the information seems to travel up my brush, through my arm, and into my brain, where it has a better chance of sticking! The goal is not to create a forgery but rather to understand how the artist solved the problems. With our modern technology we don’t have to travel to Paris or Madrid and apply for permission to copy the works; we can get an image off the internet, or even scan a photo in an art book to get surprisingly clear images to work from.

4. “Attack your weakness.” My friend Dan Gerhartz once said that to me; I don’t know if he even realized how profound a statement it is. A few years ago I was having trouble painting hands, so rather than seeking out poses where the hands were hidden I made a concentrated effort to improve. I got the George Bridgeman book, “A Hundred Hands,” and copied every illustration. It took me six months, but problem solved!

5. Take a class. With the expanding number of schools and ateliers it’s easy to sign up for an evening or weekend class. Again, thanks to our new technology we can take online classes with instructors who are half a continent away. Most of today’s representational masters also teach workshops.

In my case I learned much of my pastel technique by taking workshops year after year from the great Harley Brown. Even though I now teach workshops myself, I still try to study with an artist I like at least once a year. You can also get instructional DVDs.

(Hint: treat art workshop DVDs like a class. Stop the video after each section and practice the techniques shown at your own easel).

6. Paint from life. This probably should have been number one. The camera lies to us! There are four key elements to a representational painting: shape (drawing), value, color temperature, and edge. In a photo, three of the four are ALWAYS wrong! Values are the worst offender. The two or three darkest values turn into black, and the lightest areas get “blown out” to pure white. In a photo all edges are equally sharp . . . but that’s not the way we see. (The center of our field of vision is sharp, but the periphery is in soft focus. As we glance around a scene we can see each edge sharply — sequentially, but not simultaneously).

Color temperature is also distorted. We are limited by the phosphors in our computer screens, or — worse yet — the dyes in our printer’s inks. The fourth element, shape, may or may not be distorted, depending on how close we were to the subject when we took the photo. If we work exclusively from photos we become really good . . . at painting inaccuracies! There are a couple of other benefits to working from life. It imposes a time limit that forces us to be selective. It also forces us to “Be Here, Now”; in other words, “mindful” in the Zen sense.

7. Set aside regular times to practice. I’m also a musician, and I learned that the time to practice your arpeggios is not when you’re on stage! Even before I was a full-time artist I would make sure that before I went to bed I drew at least a head in my sketchbook. It’s better to draw or paint for 15 minutes per day, five or six days per week, than to paint for five hours one day a week. Behavioral scientists say it takes 21 days to establish a habit.

8. Get feedback. It helps to have a fresh set of eyes look at our paintings. We pour our heart and soul into our work, and it can hurt when someone points out the flaws, but as Nietzsche said, “ That which does not kill us, makes us stronger!” I regularly paint with Dan Gerhartz, who is one of today’s living masters. I always bring some of my work for critique. But I also ask my other less-accomplished artist friends, “What do you see?”

My non-painting wife has a great eye; I ask for her feedback on every piece I do. Here’s a hint: Thank the person for their critique (don’t argue with them or try to explain). “Take what you need and leave the rest.” Entering competitions is a great way to get feedback, but you have to infer it. If you don’t get accepted, look at the finalists. What do they have that your piece was lacking?

9. Find a mentor. Someone who you respect and who is willing to give you honest guidance. I have been fortunate to find several great mentors who have been crucial to my development. I was in the Saturday program at the American Academy of Art in Chicago. In the morning I took life drawing with the legendary Bill Parks. He was my first mentor. He was a great teacher (as evidenced by the impressive list of professional artists who were his students), but he was also a great human being! One day a camera crew and newsman from one of the Chicago TV stations came to our class to interview him. I remember that at one point the interviewer asked, “Where are your works?” Mr. Parks gestured toward the rows of students at their drawing benches and said, “These are my works.”

Where can you find someone to be your mentor? The easiest way is to take a class or workshop and then ask for permission to send images to them for critique. Most artists are willing to share what they know. If the chemistry is right, the relationship will naturally grow. Don’t be afraid to ask the important questions; for example, “What do you think I should be working on now?”

10. Fix an old painting. This is kind of a quirky way to improve, but every once in a while I will “fix” an old piece that hasn’t sold. Time and my own improvement (that’s encouraging) make it abundantly clear what is wrong with the painting. The remediation itself can be a great learning experience.

For some reason I seem to get a number of physicians as workshop students. One of them told me that in the medical field they say, “Take one and teach one.” Meaning learn new material by taking a course, but cement it by teaching someone else. I have found that every time I teach a workshop I paint better when I come back to my studio. Teaching forces one to clarify and simplify.

There are probably a number of ideas that I have left off the list. I’d love to hear of them if anyone wants to give me feedback. I guess the key is to view oneself as a perpetual student. I want to be like the famous artist in his 80s, who said on his deathbed, “So soon? I was just starting to understand.”

ABOUT THE AUTHOR

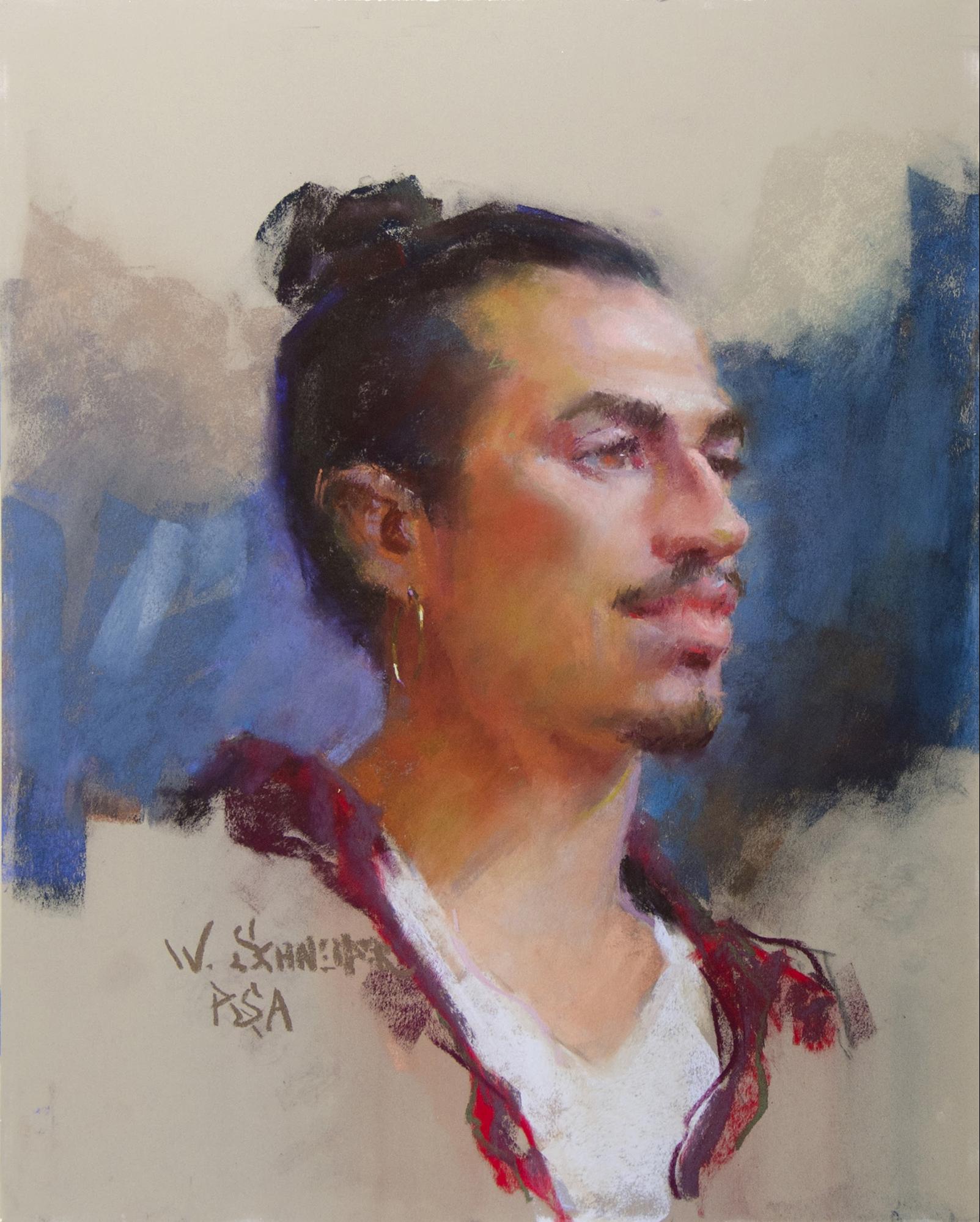

William A. Schneider’s work has evolved since he finished his studies at the American Academy of Art. He credits the many hours he spent studying and copying masterworks by Nicolai Fechin with loosening up his brushwork and approach to edges.

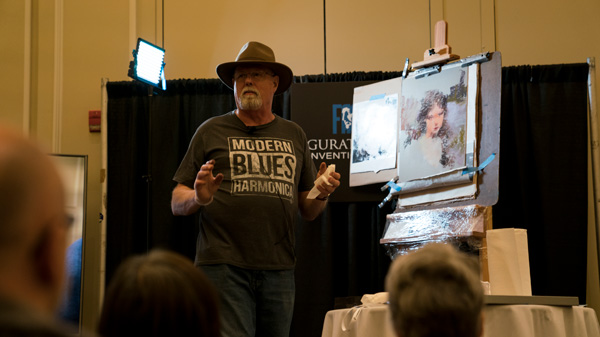

Schneider has won awards up to and including “Best of Show” in most of the national juried representational exhibitions. His work has also been featured in publications including Art of the West, Fine Art Connoisseur, Southwest Art, International Artist, The Artist’s Magazine, and Pastel Journal. His instructional DVDs are distributed by Liliedahl Video Productions and he has demonstrated his painting techniques at the Figurative Art Convention & Expo.

He was awarded signature status in Oil Painters of America (OPA). In addition, the Pastel Society of America has recognized him as a “Master Pastelist,” IAPS (the International Association of Pastel Societies) has named him to the Masters’ Circle and AIS made him a Master Signature Member (AISM). Visit his website at SchneiderArt.com.