The Dutch artist Annemarie Busschers (b. 1970) is a master at painting portraits and depicting ordinary people by capturing their marks of life — by recording their layers of skin, as she describes her method. Trained in realism at the Minerva Academy, in the northeastern city of Groningen, she inherited the centuries-old tradition of Dutch and Flemish portraiture. This was not an easy path to pursue as so many famous artists had preceded her, from Van Eyck to Rembrandt, Hals, and Gerard ter Borch.

Seventeenth-century Dutch portraits reflect the Calvinist mindset, often characterized by sitters posed undemonstratively in dark clothing against an evenly lit and colored background. These pictures differ from their European counterparts, which often present sitters in a more colorful — a more Baroque — way, preferring a full-length pose with props or glimpses of countryside beyond as signs of wealth.

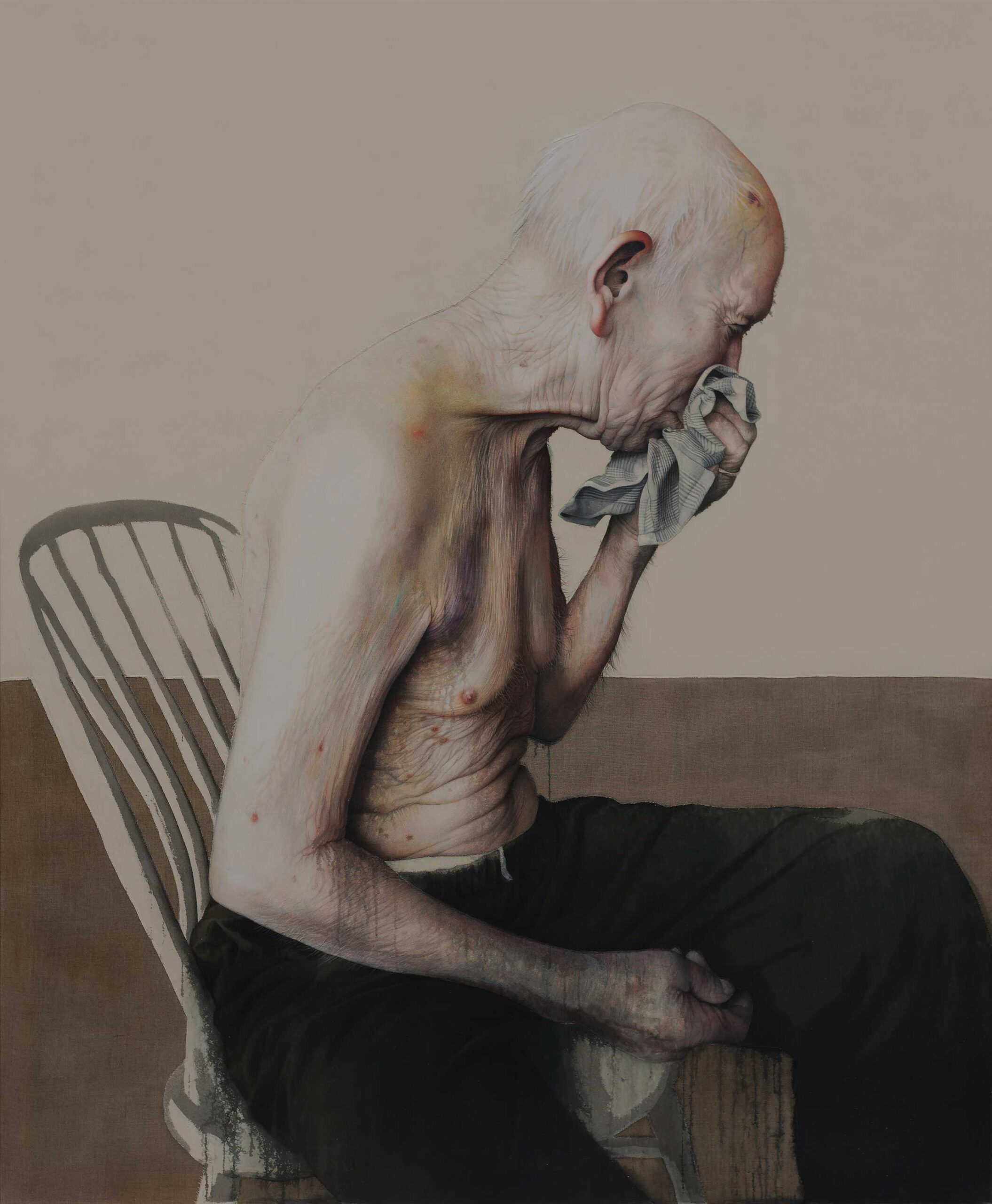

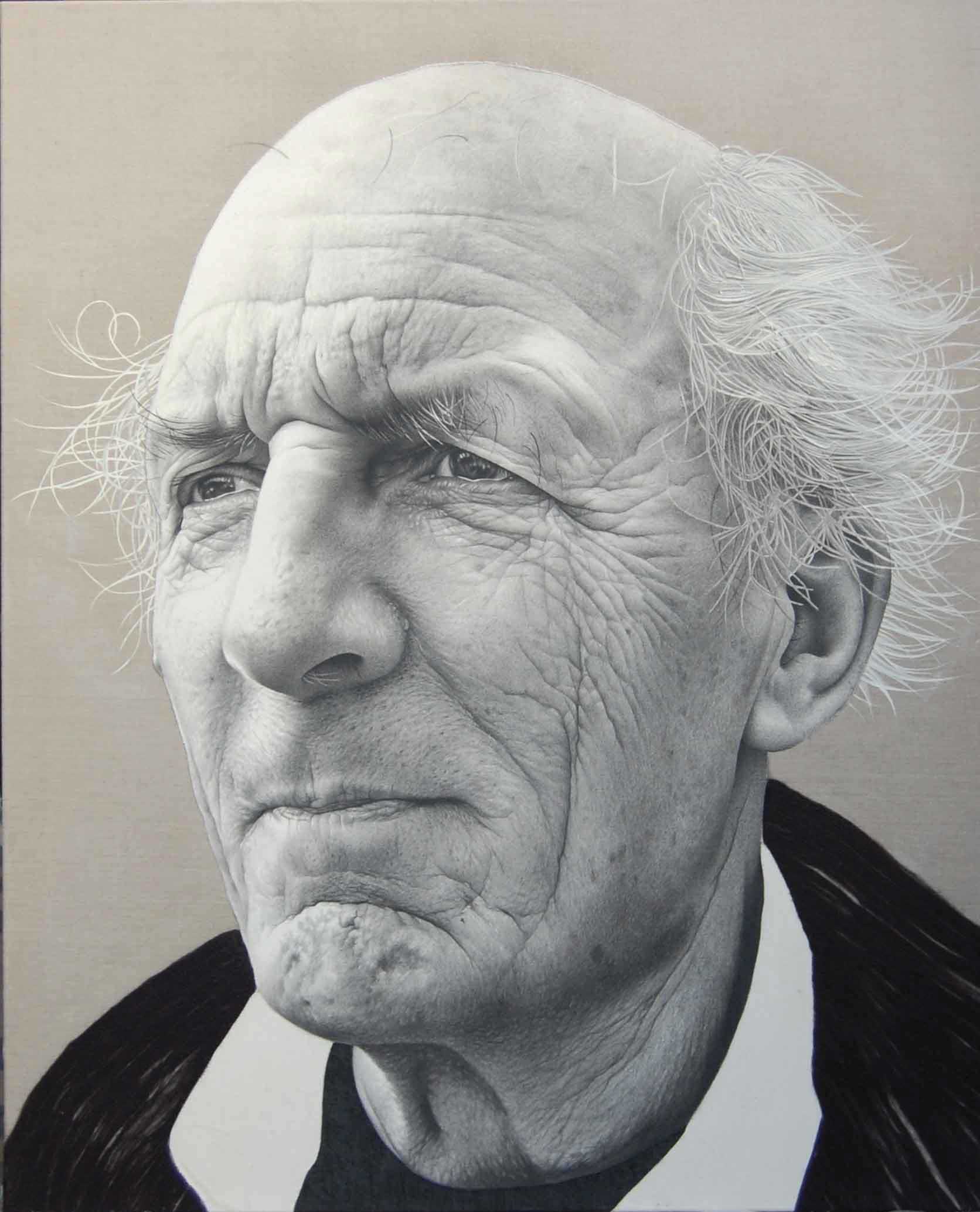

Like her 17th-century Dutch forerunners or, going further back, the sculptors of classical busts, Busschers depicts sitters either from the waist up or from the shoulders up. They are often set against a plain or evenly colored background that draws all attention to the person, preventing us from getting distracted by elements that would lessen the portrait’s impact. This is about as far as the comparison with her Old Master predecessors should go. Busschers strives to capture purity and, at the same time, a reality attained through looking intensely, without judgment, enlarging and enhancing the details she sees.

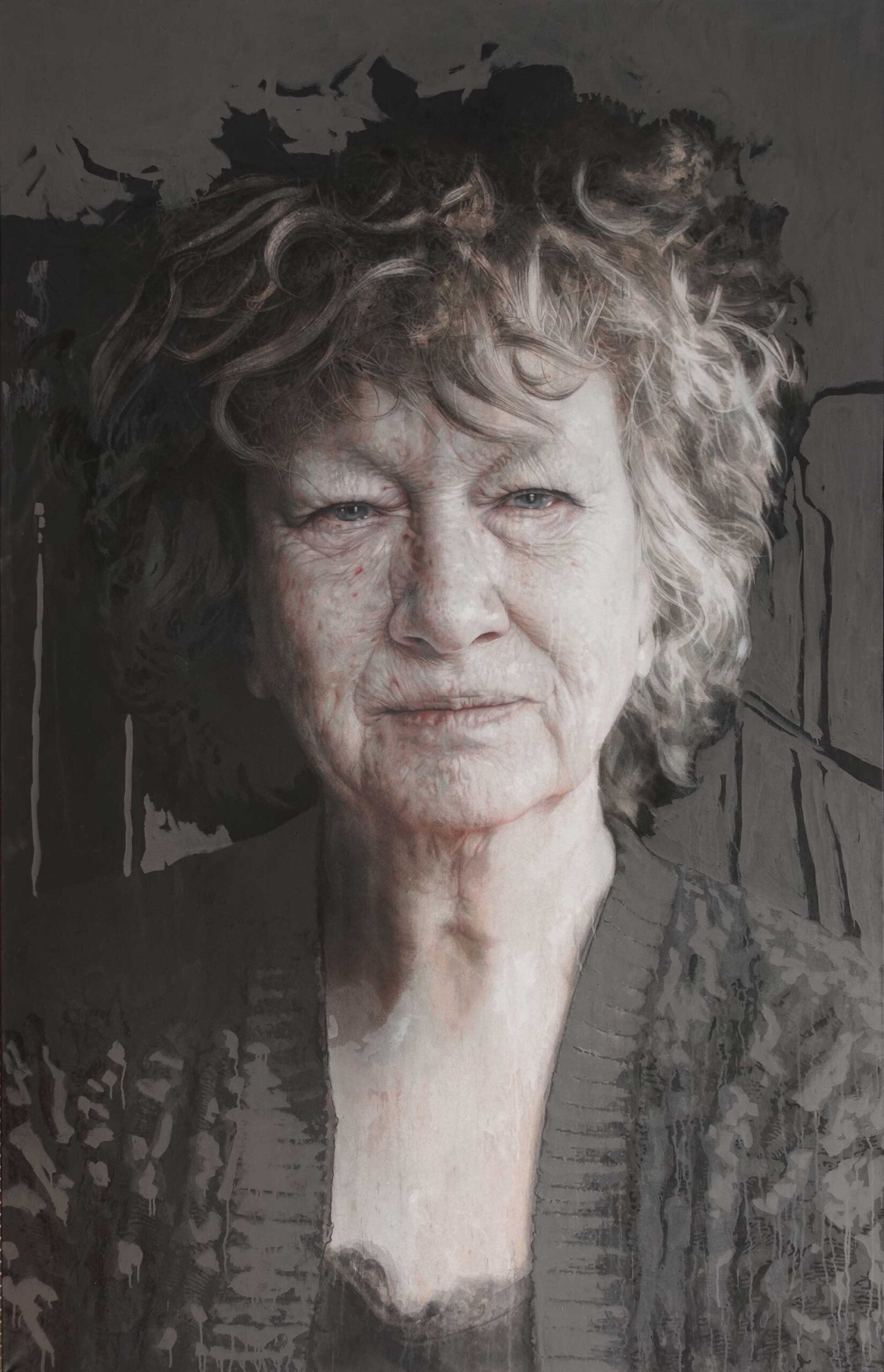

Her portrait of Jacoba Wijk, for example, deploys sober monochrome colors that give the image a quiet radiance. The sitter’s gaze is aimed directly at us, yet somehow turned inward. Wijk is left with her own contemplations. Contrasting powerfully with the dark clothing, the light on the right side of her face brings out the whiteness of her skin; it is almost a strange contradiction, then, that most of the picture’s coloring can be found there as well as in the hair. It is her face, wrinkles, and eyes that give this woman a kind of majesty. Her sober attire and hair disappearing into the background do not distract the viewer, whose attention returns to the face time and again, to these piercing eyes that seem to observe us while holding us back as well.

Portraits of Life

Busschers deserves her place among our era’s most important portraitists. As is often noted, she does not seek to create beautiful or graceful images. Indeed, she admits, “I do not paint to caress egos,” a rejection of the fact that portrait commissions have usually been (and remain) about the ego, or about the purity of a specific age, which is why many parents like having their children captured forever at a moment when life has not yet written anything on their faces.

Her Process for Painting Portraits

Busschers’s painstaking attention to details does not necessarily mean she is a realist: in fact, she enlarges the details that ultimately construct the entire image. Her priority lies in the simultaneously graphic, complex, clear treatment of the subject, a feature that makes her art immediately recognizable and contemporary.

Before starting work, Busschers takes photographs of the sitter in order to create a certain distance from him or her. By looking through the camera lens, she sees details that would normally be hidden by light or a conventional perspective.

These photographic studies often lead to an image unlike the way sitters see themselves — like looking through a mirror that brings out features we wouldn’t see right away. Consider how you see yourself in a looking glass: it always differs from how other people see you, and, after all, the mirror’s image is reversed to begin with. In this sense, our mind plays tricks on us, constructing our self-image by blocking out certain actual aspects.

Busschers’s works are literally built up in layers, with materials that might include graphite, oil pastel, chalk, acrylic, epoxy, wax, rubber, linen, cotton, felt, paper, cardboard, and even wood. By combining drawing, painting, and sculptural materials, she produces a complex work far more powerful and textured than one made only of (for example) graphite on paper.

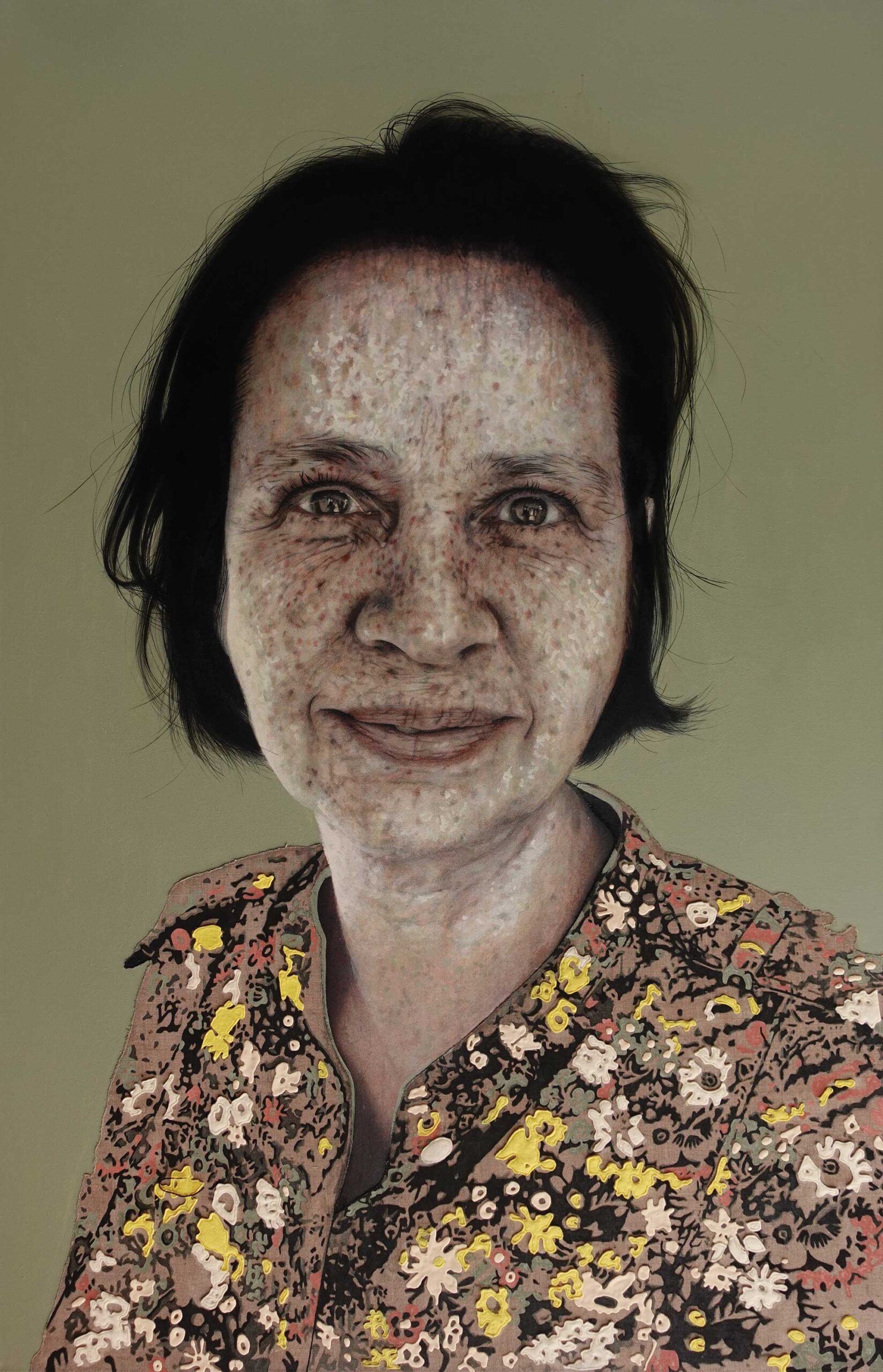

This approach helps make Busschers’s work almost scientific. In “Annabelle Birnie,” for example, the face teems with tiny details and freckles, and the eyes sparkle with life. The energy radiating from it is underscored by the blouse’s adornment with many colorful flowers. Here the blackest black is created not with paint or pencil, but with felt, its surface as irregular as skin, like the clothes we wear, like life’s traces.

Such details force us to apprehend Busschers’s art with all of our senses. In fact, viewers regularly try to touch her works, as if they can’t believe what they are seeing. Her diverse textures entice them to do so, reminding them they have been raised to look but not touch. Busschers subverts that norm, playing with the fact that what you see from a distance is not what you get up close.

To enhance her scientific effect, Busschers bypasses the normal scale of bust portraiture that fits nicely above the sofa. Instead, her monumental formats overwhelm the viewer: there is no escape, and we must allow ourselves to be absorbed by it, or perhaps to step back to experience the full image. This scale makes Busschers’s sitters larger than life, creating a distance between them and the viewer, even between them and the artist. Busschers also realizes that, through most of art history, large has meant important. By blowing up her imagery of people who are often unknown, she instantly makes them significant.

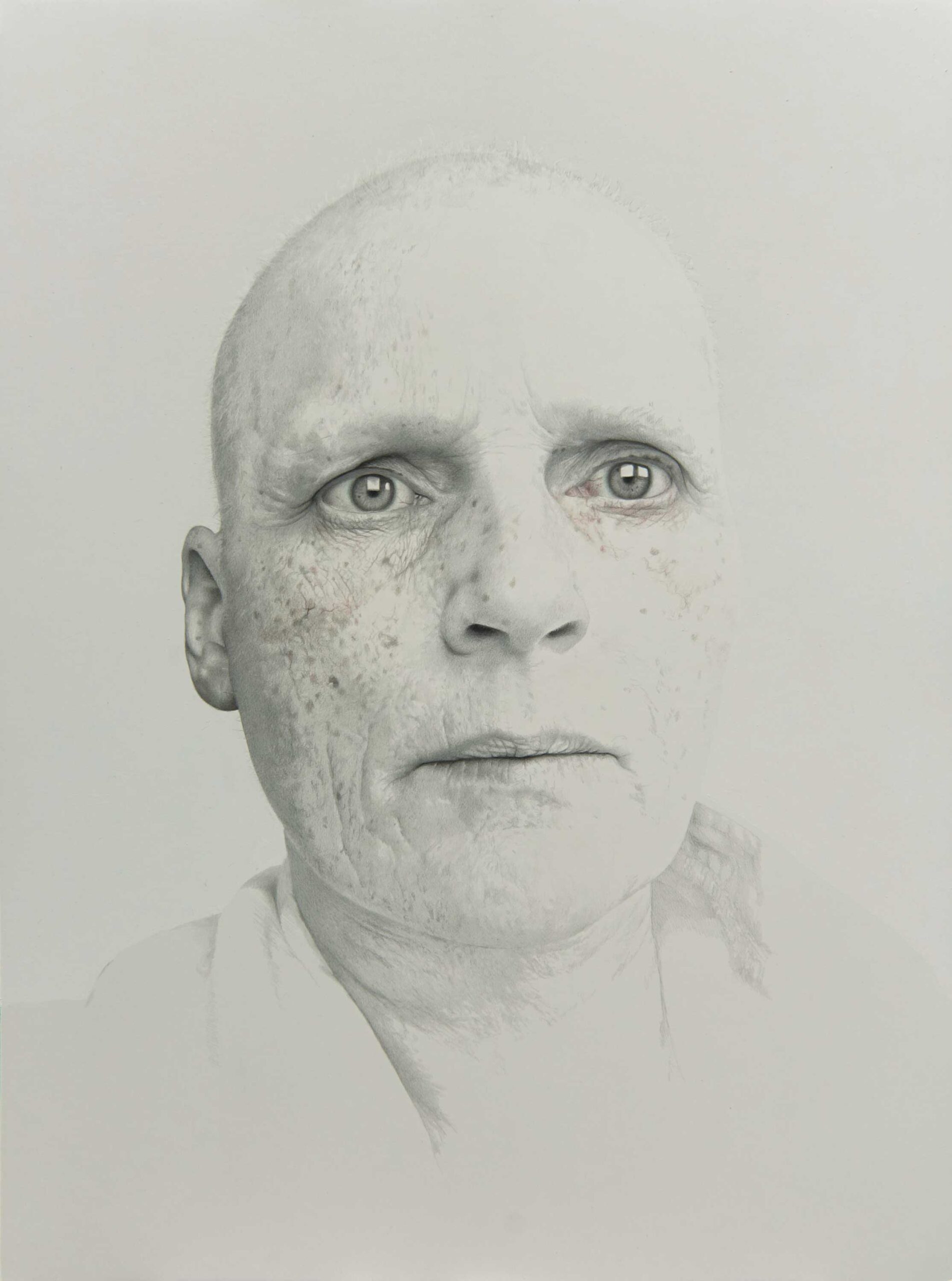

Although Busschers has won applause for her unrelenting directness, what really makes her portraits so powerful is the authenticity of her interest in, passion for, and involvement with each sitter. A telling example is the multi-layered portrait of her father, Bram Busschers. First we are drawn to his eyes, which convey both introspection and wisdom. It is his mouth, however, that suggests one can never say everything one wants to. The plain background and sober clothing convey modesty and dignity, but the quietude and calm that often accompany age are what seem more striking here. Through her layers of interpretation and a variety of tangible, physical skins, Busschers renders the circle of life complete.

About the Author: Patty Wageman is an art historian and writes about art regularly. She has developed many internationally acclaimed exhibitions for museums in the Netherlands.

Read the full article in Fine Art Connoisseur (March/April 2023). Subscribe here.

Browse more articles on painting portraits, figurative art, and artists here at RealismToday.com.

Thank you for writing about AnneMarie Busschers. I had never seen her work. It is interesting. I like it very much. I wish I could see it in person, touch it – gently. She would, almost have to make her portraits large to include so much detail and such a variety of materials. A lot of glue, I assume? nv

Comments are closed.