The American artist Michael Shane Neal uses two palettes for his portrait painting sessions. One of them, smeared with varying hues, he holds aloft in his left hand while working on a canvas, his live subject often posed in a chair nearby. The other palette rests on the fireplace mantle of his 10th-floor studio in New York City’s National Arts Club.

When Neal picks it up, he claims to feel a certain energy emanating from the wood, for it belonged to John Singer Sargent. “I keep his palette in a Plexiglas case,” says Neal, “but I take it out often and hold it, knowing not only that it was Sargent’s but also that it was given to me by Everett Kinstler.”

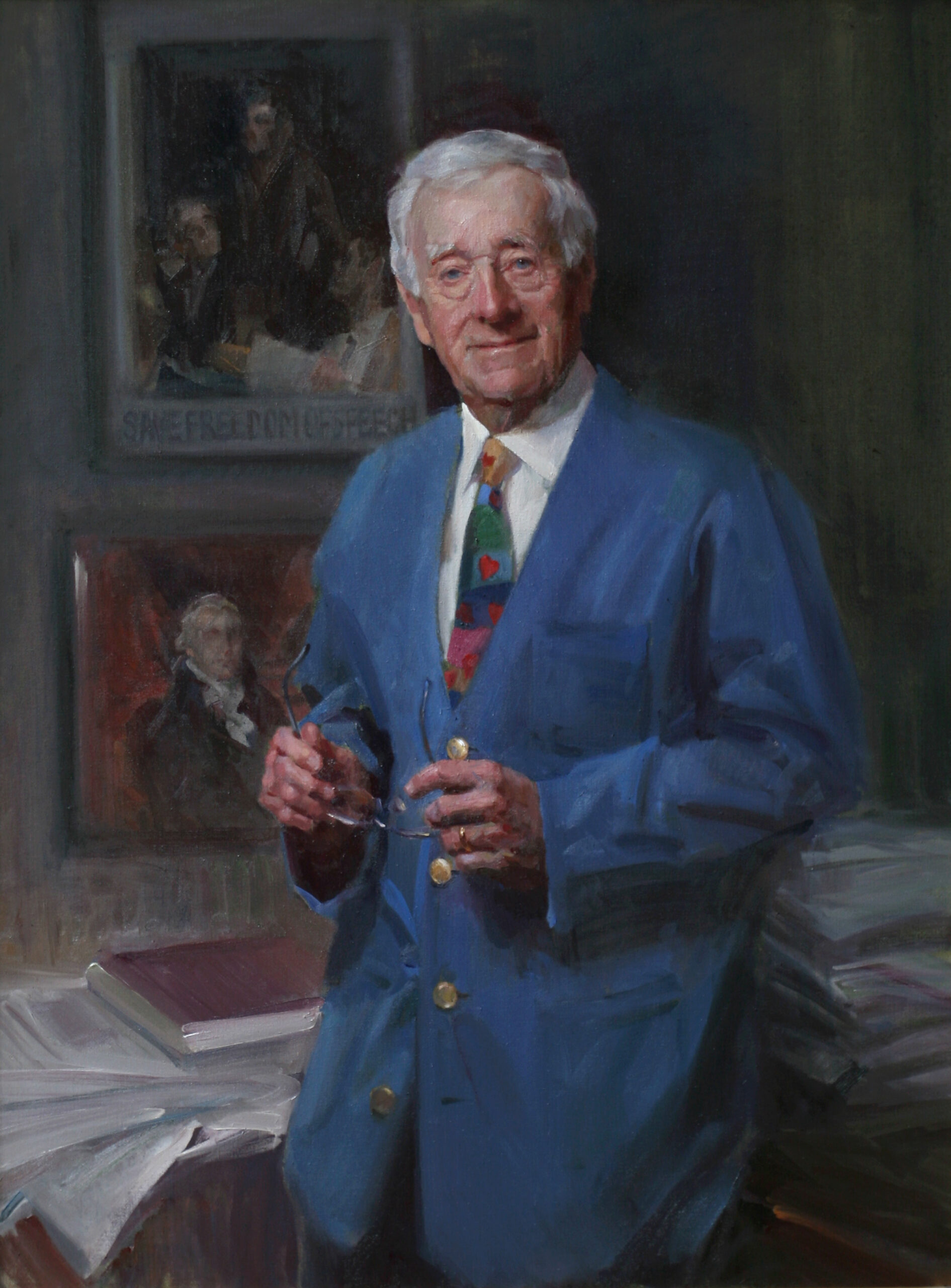

Neal refers often to the great American portraitist Everett Raymond Kintsler (1926–2019), who was his longtime mentor. “It was Everett who instilled in me a love of Sargent. He opened so many doors for me.” Alongside Sargent’s palette, Neal keeps a first edition of Kinstler’s iconic 1987 book, Painting Portraits, which he admits to having read “at least 20 times.” He says, “I first came across it during college, and the moment I finished reading it, I said to myself, ‘That’s what I want do, to be an artist who paints portraits.’”

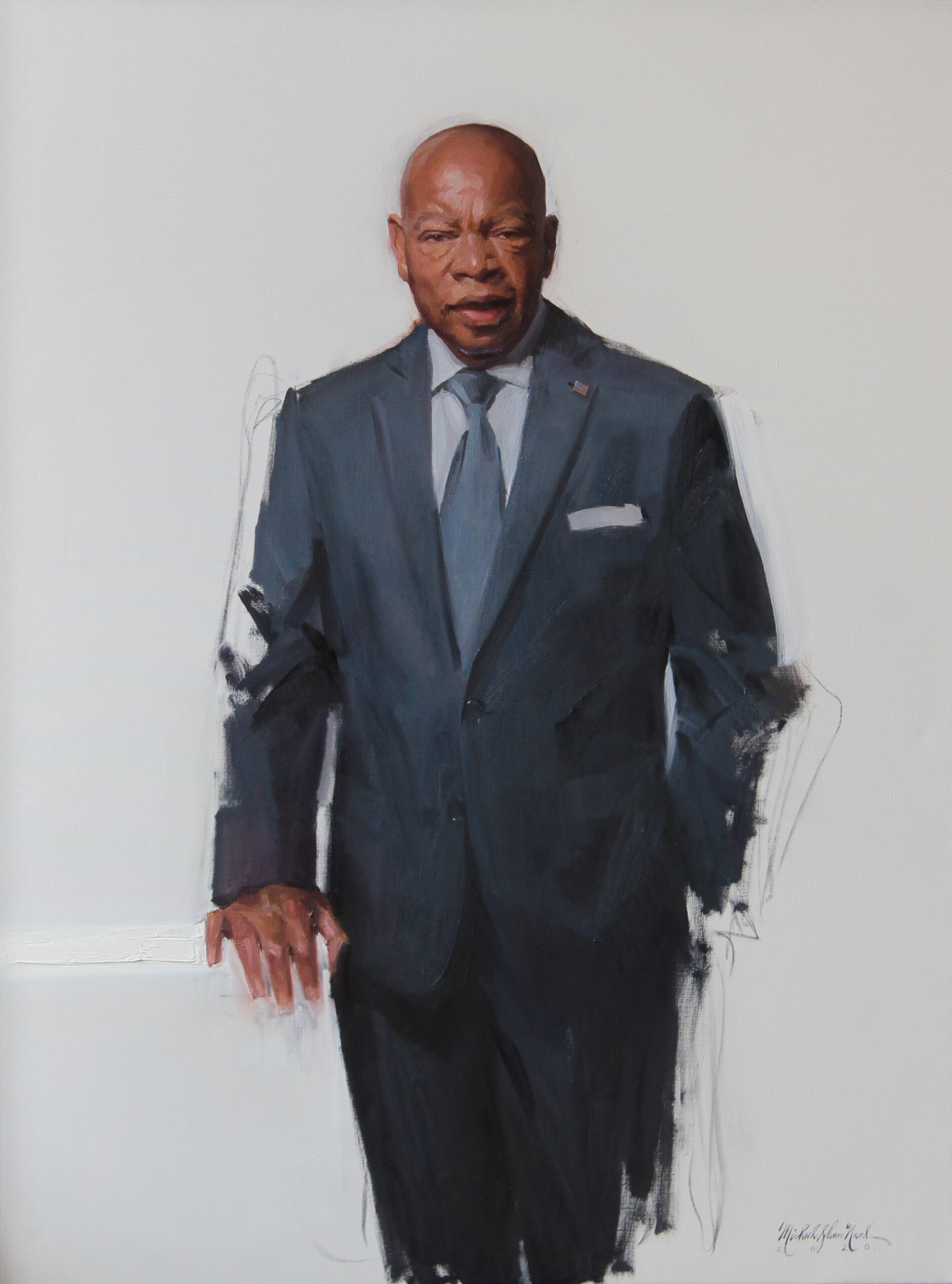

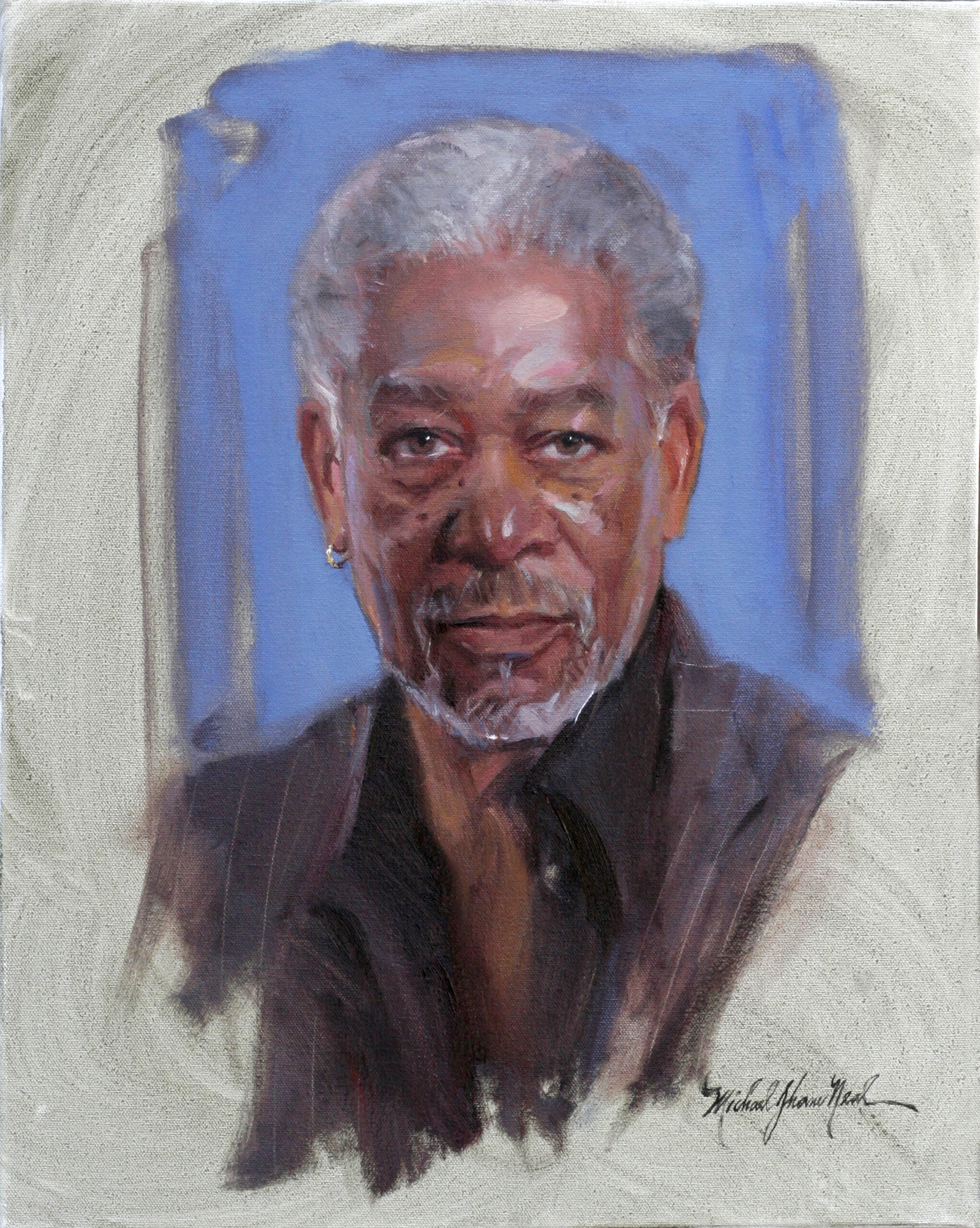

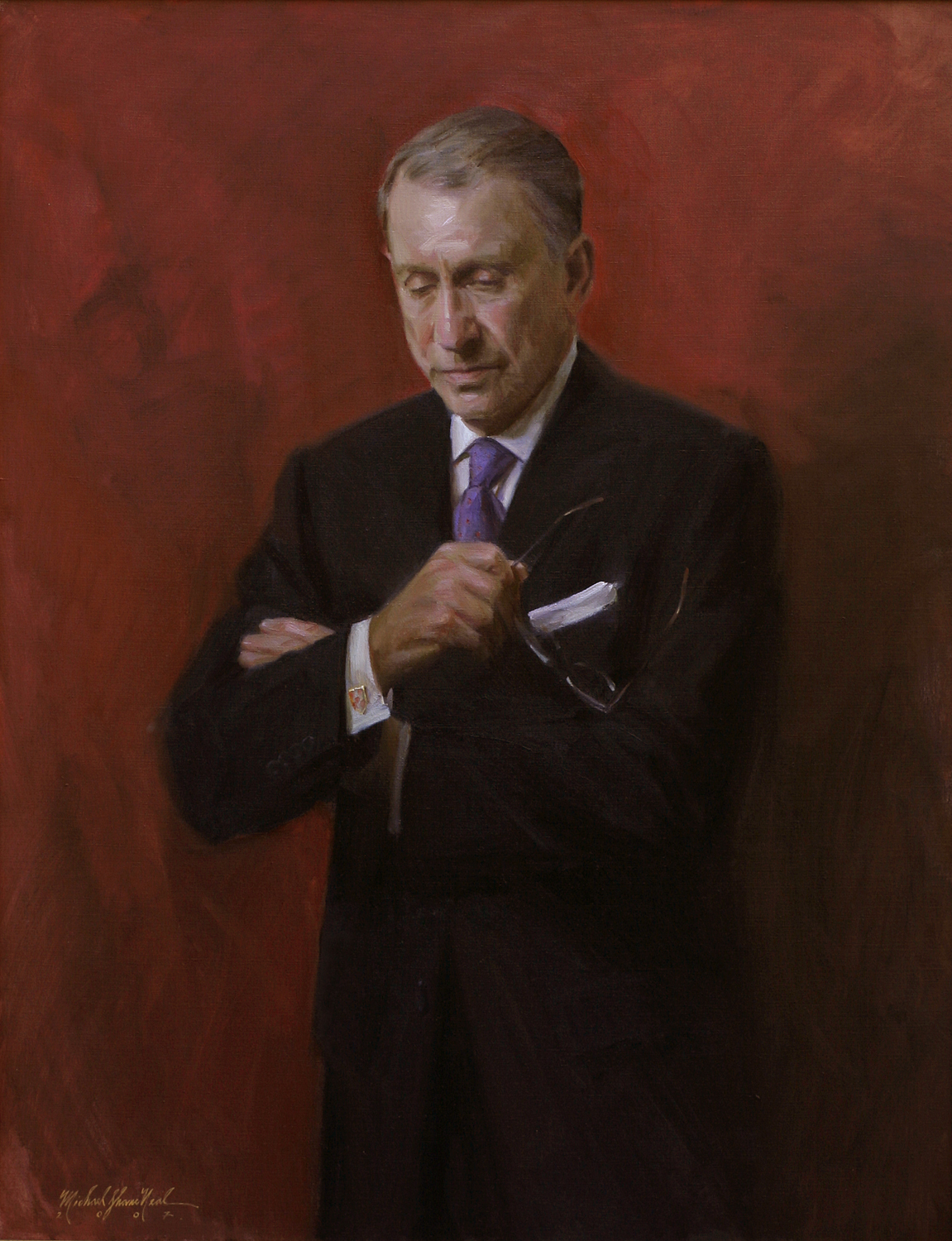

Neal, who has completed some 500 commissioned portraits of figures as illustrious as Supreme Court Justice Sandra Day O’Connor, Congressman John Lewis, and Senator Bill Frist, along with ambassadors, Hollywood stars, and corporate leaders, cites Sargent’s 1892 portrait of Lady Agnew of Lochnaw as a work that “represents Sargent at the height of his powers with the brush.” Acquired in 1925 by the National Galleries of Scotland, it depicts the regal society woman lounging in a Louis XVI–style chair, an extravagant lavender sash wrapped about her waist.

“Every time I see this painting, either in a book or in person, I learn something new,” Neal notes. “If you look at the sash and flowing gown, you can detect ridges of paint where Sargent made changes, and also evidence of ghost images where he shifted such elements as the pendant around her neck, and a cutting away of her jaw and neckline. A common misconception about Sargent is that he put it all down at once on a canvas, but this reveals that he struggled with his paintings.”

As a prolific working artist, Neal is especially cognizant of the time it takes to complete a portrait. From his research, he relates that Sargent worked exclusively from life, with a subject needing to sit some 15 or 20 times for three-hour visits. “Today I’m lucky if I can get a subject for two or three sittings,” Neal confides. So he often works from photographs. “Some people ask if photography killed portrait painting,” he continues. “I say that photography saved the genre.”

Lady Agnew is reported to have sat just six times as she was recovering from a lingering case of influenza. “Some have claimed that she’s reclining because she was not strong, but I’m not sure I buy that explanation,” says Neal. “It’s more likely that Sargent posed her that way because he was embracing some modernism. She was a cutting-edge lady of her day and she struck a less formal pose, perhaps even a slightly seductive one. When women of that time saw the finished work, they likely said to themselves, ‘I want to be that woman.’”

By sheer coincidence, Neal now occupies the very studio in the National Arts Club where Kinstler lived and painted from 1953 till his death in 2019. (Neal has another studio/residence in Nashville.) As he works in his expansive, north-facing perch, he claims that “Everett’s voice is still clear in my mind, and I can feel him here, as I sometimes do Sargent. I work in a space that’s inspiring. I think of Sargent and of the Lady Agnew portrait as benchmarks, signposts for what to do and where to go.”

***

Published six times per year, Fine Art Connoisseur is now a widely consulted platform for the world’s most knowledgeable experts, who write articles that inform readers and give them the tools necessary to make better purchasing decisions. Fine Art Connoisseur‘s jargon-free text and large color illustrations are attracting an ever-growing readership passionate about high-quality artworks and the fascinating stories around them. The above article originally appeared in Fine Art Connoisseur. Subscribe here.