Communities run on volunteers: We walk dogs at animal shelters, we take meals to those who are unable to cook for themselves, we gently rock newborn babies. Sounds lovely, yes? Treacy Ziegler is an artist who found her calling to volunteer at another end of the spectrum: She spends her time at a maximum-security prison, teaching still life drawing to prisoners.

In the following guest blog post, Treacy tells us what it’s like to bring her still life setup elements and her experience to the prison, and the one thing she admitted (and the prisoners agreed) was a “stupid thing to say.”

Yours in art,

Cherie

P.S.

Have you ever volunteered your artistic talents? Tell us about it in the comments of this blog post!

Still Life with Prison Bars

By Treacy Ziegler

In prison, time can be ignored. The prisoner Joe says he no longer looks at a clock. “I don’t think about time. What difference can it make to me when I’m serving life without parole? Every day, every minute is the same.” His statement is without anger or regret. But in reflecting the uselessness of measuring temporal change in prison, I wonder if Joe’s statement suggests that the prisoners in my art class have an affinity for the genre of still life.

As arranged objects, some still lifes present as visual pleasure while others have symbolic meaning. Think of the religious still life with the skull and fly, or a Dutch still life of opulent middle class pleasure. But in art school I learned that beneath these arrangements, a still life screams of a problem more basic than symbolic meaning or aesthetic pleasure.

While nothing is profound in realizing that life is constant change, it wasn’t until art school, when asked to draw from life, that I was confronted with relentless change on all levels. Despite Joe’s assessment of sameness, nothing stays the same. Landscape painting is complicated by our moving relationship to the sun, changing light and shadow patterns that, in turn, alter the shape of things upon that landscape. A stationary nude is never stationary. Skin and muscle are constantly challenged by gravity, not only shifting the pose but also making the person look different. Drawing from life makes explicit the world’s ontological restlessness, compounded by the difficulty in reconciling that movement onto the nonmoving paper or canvas.

Art school, sensitive to this restlessness, dedicated an entire room, known as the still life room. This room provides an antithesis — albeit abstract and incomplete — to this metaphysical squirming. In the still life room, movement is slowed for beginning students; artificial light provides constant light and shadow masses; plastic flowers interrupt the cycle of living and dying.

But even within the stasis of the still life room, movement is not stopped. A fellow art student, Leslie, painted so fast and with acrylics so thick that at the end of each class, her paintings, pulled by gravity, incessantly slipped off the canvas into a pile of sludge upon the floor, arranging into a newly formed still life.

The still life room had several different stations of arranged objects, but none were arranged with the concern for symbolic meaning. Content and meaning were abandoned for learning composition, replacing meaning with form; diagonals against verticals against horizontals with tonal or color variations.

Can I ask the prisoners to draw without content and meaning? Will they be pulled into a world of abstract form without reference to objects with meaning? Most people cannot. Insisting that meaning is the door to any experience, many museum visitors demand, “What does the painting mean?” I compromise and bring objects for the prisoners to draw. By doing so, I can’t help but also bring the inevitable meaning that surrounds those objects like an opaque dirt cloud.

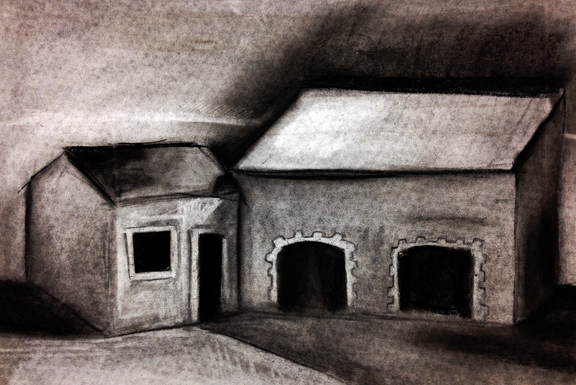

I bring a small toy farm, a provincial farm from France; a strange farm to bring into prison. It does support that form is more important than content in learning to draw. The farm is simply a white structure providing surfaces for reflecting light and extending space in several directions. I borrowed this farm from my friend’s young kids 18 years ago when I wanted to simulate an abstract space in my studio to draw — like the still life room.

I never gave the farm back to the young kids and now they are too old, no longer wanting to explore this simulated space. The prisoner Nathan is interested in such space and built a tenement construction. I initially thought Nathan’s building would be excellent for the class to draw. I liked the building’s dichotomy between exterior and interior compartments, its undisclosed meaning of space with the arbitrariness of boundaries. When I told Nathan how much I liked the construction, he worked harder on it. Unfortunately, in doing so, he made it less abstract by adding details. Overly defined, the building became flat. We went back to drawing the provincial farm; no people, no animals, no details, but haunted by living and therefore, straddling between meaning and no meaning.

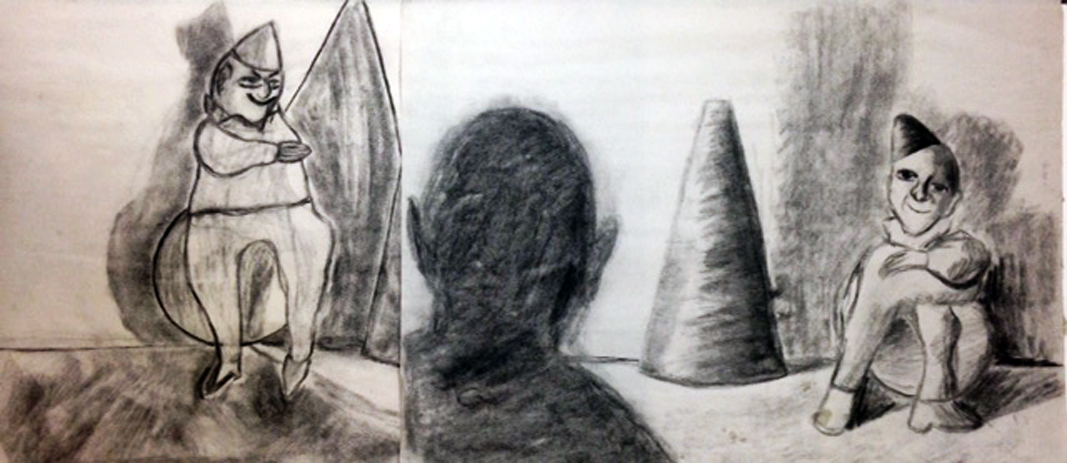

Another object I bring into class is a vintage puppet from the 1940s. It is a clown. Something about this clown makes me think of The Twilight Zone or Chucky from the horror movie. Another prisoner, also named Joe, suggests the puppet is Pennywise from Stephen King’s novel. I don’t tell students this strange puppet is the only thing my mother gave me. Not true, an exaggeration. I remember it as the only thing my mother ever gave me and, therefore, it becomes the only thing. But all of this is very illegal to tell the prisoners. Illegal not because it’s false, but because it is personal, personal regret putting a hole in my armor. This personal breach, the prison administration tells me, will lead me into bringing knives and cell phones for the prisoners to escape.

But I like the clown with its 1940s casting of a plastic head that appears different than today’s plastic, and a floppy body. The floppy body is dressed in a one-piece white flight suit with red polka dots. He wears large white shoes made of the same plastic as his head. I assume it is a male clown. The floppy body moves according to strings attached to a wooden bar. It is a marionette; it is Chucky the killer-clown-marionette that I bring into a maximum-security prison for the prisoners to draw.

I bring in a plastic dragon, knowing prisoners like drawing dragons. In my class, the third Joe draws them constantly (so many Joes in prison, it could be a fortuneteller’s warning to parents: Name your child Joe, and he will live in prison). I tell number 3 Joe, “If you want to draw dragons, then draw this one; not one from your imagination. Any dragon drawn from your imagination will be limited because you haven’t looked at the dragon’s forms defined by light and shadow and extended through space.” Of course, this is a stupid thing to say; all dragons are imaginary. And the students eagerly agree, “Yes, a stupid thing to say.”

If dragons are imaginary, what difference is there between drawing this plastic dragon and drawing one from imagination? When the prisoners don’t know the answer, I suggest it’s the limitation of the imagination bringing everything imagined under the single filter of the self: The imagination needs the outside world to expand its dimensions. If the class were to build a sculptural dragon (even from imagination) and then draw it, the imagination’s limitation diminishes because of the phenomenal experience of the dragon — defined not by thought but through vision — light and shadow and so forth. We don’t have materials for building dragons, and the class draws the plastic one I bring to class.

Expanding the prisoners’ knowledge of art history, I bring examples of Giorgio Morandi’s still life paintings. Despite Morandi’s reputation as the primary 20th century still life painter, the prisoners are unimpressed, and Douglas states, “I wouldn’t give you five cents for that painting.” (Douglas also said that about Rembrandt.) While I love Morandi’s paintings, I understand Douglas’s dislike. Painting after painting, Morandi presents groupings of bottles. Many of the bottles stand shoulder to shoulder, extending across the canvas. Many of the paintings break compositional art school rules; tangents are everywhere. But the prisoners are bored, and breaking their boredom, I mimic Morandi’s mother with whom he lived, imagining her asking, “But, George, why so many bottles? Why can’t you draw a nice girl for once?” Douglas agrees. All the prisoners bring their drawings of smiling, big-bosomed women to class.

But why the bottles? Certainly, there is no symbolic meaning in bottles for Morandi. In fact, it is reported that Morandi removed labels of the bottles to bleach any signification, painting the bottles a flat color to minimize reflection. Like the still life room, he created arrangements that reach beyond conceptual meaning, reaching even beyond elements of form to basic ontological parameters — here, there, absence, presence. The appearance of stillness in Morandi’s paintings, like the still life room, underscores its unattainability outside an ideal. There is tension between the bottles — invisible vibration of atoms, or the moment before an arrow is released, making restricted movement more powerful than action.

With this thought, I inevitably think of prisoners and their unique experience living in ultimate restriction. What would Morandi draw if he were a prisoner? Would he experience it not as a sentence but as an opportunity to penetrate beneath the stillness? Would Morandi experience his stripped identity as restriction or freedom? After all, what is the price of meaning?

In some ways, meaning is similar to the still life room; both are responses to constant change. The still life room slows movement, and meaning stabilizes life for understanding. And yet the still life room is different than meaning: The still life room controls movement in order to see differently; meaning controls in order to see sameness, such as enabling the chair to be always understood as a chair. While meaning helps in daily life, it can also enforce stagnation — like understanding a silly clown as forever associated with a painful relationship. Meaning and memory are potential traps of control.

But Morandi strips the bottles of meaning, breaking them from the past, and by doing so, allows the bottles to be unique. In creating this state of non-meaning, Morandi creates freedom — the bottles will not be conquered into meaning.

What would Morandi draw in prison? He would probably draw big-bosomed women and celebrities. Prison seeks absolute control through meaning: an inmate can only be an inmate. Because of this, still life rooms are dangerous in prison. It is a room — perhaps a shrine — reminding that life is forever changing, and absolute meaning is meaningless.

***

Treacy Ziegler has been making art for the past 25 years. In addition to teaching in prison, she volunteers as the program director for the Prisoner Express, a through-the-mail distance learning program for prisoners. In this volunteer capacity, she develops art curricula for 4,000 prisoners across the United States, representing every state and around 700 prisons. Please visit her website at treacyzieglerfineart.com.

This blog post is sponsored by the PleinAir Salon. You could win $15,000 if your painting is chosen as the Best Painting of the Year!

$27,000 in total prizes! The current competition is now open and accepting entries.

Thank for this post.

I accepted Eric Rhoads invitation to be on the faculty of Plein Air Santa Fe Convention and Expo. as one of the presenters on Eric’s early morning Marketing Boot Camp. I did this voluntarily, without any monetary compensation, because I believe its part of my mission to help educate artists, particularly women artists, by giving them professional marketing tips.

It was an honor and a pleasure to be included along with Buddy Odom. I also respect Eric Rhoads for all he is doing to promote Representation Painting as well as Nature’s beauty. Certainly our world needs the beauty of Fine Art more than ever,…

Best wishes,

Kristen Thies–Representing the art of Richard Schmid, Nancy Guzik, Kathy Anderson, Daniel J. Keys and others.Curating Fine Art Collections with Integrity Since 1998.

Hello, dear Kristen! Thank you for your work at PACE, and for sharing your knowledge with other artists. I agree that the world needs more art, always. <3

I taught drawing in a maximum security jail in Hudson WI for a year. One of my students got in trouble for drawing on his cell walls with water soluble markers. The guard told him to clean it off with his toothbrush. He refused. The guard then threatened to take art class away. He cleaned his cell walls with his toothbrush and never missed a session. I still have his drawing of the radio the jail guards gave me to take into the edu room in case “something” happened. The guards were not happy that I put it on the table in front of me and then went on to have the class of serious offenders draw it in pencil. It was a very interesting time.

It sounds very interesting – thank you for sharing this with us, and for teaching art to the inmates. I believe that if more people found a means of creative self-expression, there might be a lesser need for jails, among other institutions and elements of our culture. Best wishes~

Comments are closed.