How an oil painter’s love of the Rocky Mountain West finds its way onto canvas. Bonus: Includes a step-by-step oil painting demonstration. The following is part of a series that features the best artists who are teaching others how to paint through online workshops at PaintTube.tv. Learn how to paint wildlife such as birds and waterfowl with Dustin Van Wechel’s new art workshop, available here.

Contemporary Oil Painting > An Artist’s Romance with the Wilds of North America

BY DUSTIN VAN WECHEL

I’m going to be honest: I think for most of us wildlife artists — and we can include you plein air painters out there, too — creating wildlife art is really just an excuse to spend as much time outdoors neglecting our adult responsibilities as we can justify (at least it is for me to some extent).

The irony is that the more success one has as a wildlife artist, the less time one has to spend outdoors looking for critters and absorbing the sights, sounds, and smells of nature. There are just too many deadlines that keep us working in the studio.

In some cases, being “outdoors” to gather reference is a fairly loose term. I can’t tell you how many countless hours I’ve spent in a car — from dawn to dusk, for weeks on end, in various national parks — looking for animals. Those kinds of trips are exhausting. I certainly prefer the kinds of reference gathering trips where I can just hike out on a quiet trail through the mountains and stumble across something exciting. Those are the moments we wildlife artists live for. But when you need to cover a lot of ground, whether it’s trying to get to a specific location, or just trolling through a national park, you have to live from your car. It’s not particularly glamorous.

Memory is an interesting thing. When I think about it, those moments where I have been lucky enough to have had an extraordinary wildlife encounter — whether via the car or out hiking — are actually quite few. In the nearly 20 years I’ve been working as a full-time artist, I can think of only a handful of those times. And yet, my memory of them is so strong, and the excitement of the encounter so vivid, that it feels as though it’s happened much more often.

It’s these kinds of experiences that keep the passion I have for wildlife and nature so strong, and they have provided me a wealth of ideas from which to create paintings.

Which leads me to something I’ve occasionally been asked: From where do I find ideas for my paintings? There actually is no simple answer. As a generalization, yes, most of my concepts are inspired by my experiences in the field. They are often the end result of combining field studies, photographic reference, and sketches to create romanticized versions of the experiences I’ve had while out exploring the vast wilds of North America.

And while my process has evolved over the years, one constant remains; I’m always looking to communicate my obsession with the creatures and landscape of the Rocky Mountain West through my work.

Oil Painting: The Big Ideas Can Be Hard To Come By

Unfortunately, the ideas sometimes don’t come as easily as that explanation might lead one to believe. I often find when I’m conceptualizing a new oil painting, I struggle with not only telling a story that feels fresh and unique, but also wanting to be sure I’m creating a painting that will engage the viewer. For me, successful art should reach beyond its subject matter.

It should not only communicate the artist’s conceptual intentions, but must also give the viewer a glimpse into the artist’s personality. The subtleties of brushwork, color usage, design, etc., are all important attributes of an oil painting that help to visually define the artist and communicate what the artist is passionate about. The “Big Idea” in creating a new wildlife work should include these elements. They are all collectively part of the narrative of the painting.

It would certainly be easier to find ideas if I just relied on my photos. But, as a painter, I’m not interested in just reproducing photos I’ve taken. For this reason, I generally do not endeavor to create hyper-photorealistic work. Although photorealism demonstrates a great aptitude for draftsmanship, I feel it also often renders us out of our own work — reducing the uniqueness of our paintings to literal (and frequently generic) representations of the artist’s photographic reference.

With that being said, I do strive for authenticity in my paintings. I want the viewer to connect with the work, and I find when painting wildlife, creating a sense of realism is an important part of bridging that connection. Once the oil painting has the viewer’s attention, the viewer is then free to make discoveries within the painting of a more subtle nature.

My oil painting process begins with an idea or experience from the field I’m excited to paint — even if that idea is still a bit vague. It’s from here that I begin with a series of rough sketches (thumbnail drawings) that flesh out the idea. I often complete several thumbnails, especially when my intention is to create a complex composition, and I then look to my reference to help me bring the concept to life.

Even though it is often an experience that inspires a painting, there is much more work to be done to create a painting that might be considered art — and more importantly, art that is uniquely my own.

Oil Painting Demo: The Construction Of “Focused”

At this point in my career, the “Big Ideas” are of a deadline-oriented necessity. Shows often require the artist to have at least one major work in his or her grouping, and that is certainly the case with the Autry Museum of the American West’s “Masters of the American West” exhibition.

This is my sixth year participating in Masters and each year the show requires a signature painting to be included in the catalog. This painting is generally the artist’s largest and most complex piece. In considering what it is I’d like to paint for the show, I often look back to what I’ve done in previous years. It’s important to me to not repeat myself and so I’m looking for a concept that will feel fresh from my previous work. When painting wildlife, many of the narratives may be the same, but I believe those stories can be told in countless ways.

For this year’s Masters show I chose a mountain lion as my subject (I’ve included a step-by-step painting demonstration of it below). I knew the story I wanted to tell with this painting — on the surface the painting is about a cougar locating his prey, but there is also an underlying bit of symbolism in the painting that I’ll leave to the viewer to discover.

I knew from the outset that I wanted the painting to be relatively simple compositionally — i.e., not a lot of animals to organize or environmental elements to consider. Doing this would not only help reinforce the title, “Focused,” but would also create a sense of intimacy — the viewer might better connect with my subject if the painting was kept less busy.

Once I had a thumbnail sketch that seemed promising, I looked to my extensive reference library to help me build the painting. My reference library has been gathered over the course of nearly 20 years of being out and about in nature. It includes not only tens of thousands of images I’ve taken but also field sketches and plein air studies — all of which inform my studio work.

In the case of the oil painting “Focused,” I only required photo reference, so I began the process of sifting through images and locating environmental elements like rocks, trees, grasses, and skies as well as looking for a cougar that would work in developing the concept.

Representational artists today are fortunate to have such an extraordinary tool to use in creating works of art: The photograph. But for every benefit photography provides, it also yields great drawbacks. These include simple problems like inaccurate color representation, poor reproduction of values (especially in bright light), and photographic distortion — all of which are easily handled by the well-trained artist. But there are other issues with using photographic reference that go much deeper than simply having to adjust a color here or a value there.

Photo reference can make you lazy. Really lazy. This is especially prevalent in the wildlife art genre where we too often rely solely on the presumed appeal of our subject, distracting them from the considerations of what makes for a great painting.

For example, they too often slavishly reproduce a photo they have taken because the subject looks cute. This is not how I approach a work. The photo is strictly for reference — a tool to be used in building a greater idea. Ideas that arise from our experiences and passion for our work have significantly more impact on the viewer than a photo reproduced in paint. And while it can be more difficult for us wildlife artists who may not have built up a well of reference over decades to construct complex paintings, we should always resist the temptation to simply reproduce a photo.

Once I collected all of the photo reference required to create the painting, I moved on to producing a more finished sketch. This sketch allowed me to set all of the elements and provided a strong compositional guide I then used throughout the painting process.

Related Article > On Painting Horses

Step 1

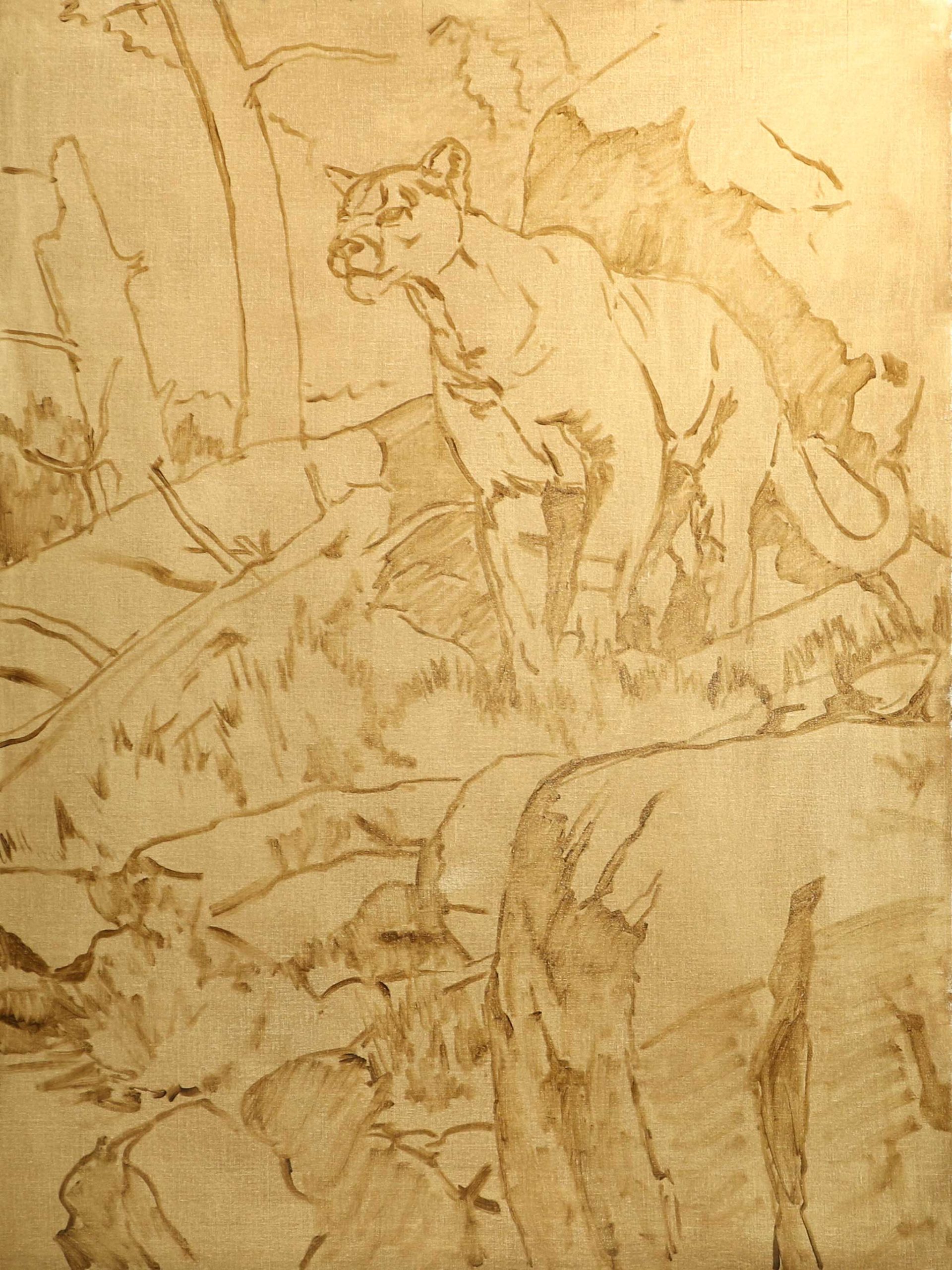

I began the painting process by toning the canvas (linen mounted to Gatorboard) with a mixture of burnt sienna and ultramarine to create a sepia tone.

I then thinned it with Liquin and wiped it onto the canvas with a paper towel. I made sure to wipe off any excess. I let this dry overnight.

Step 2

Once the toned canvas was dry to the touch, using a small bristle brush, I very roughly drew (using the same mixture of burnt sienna and ultramarine) the concept for the painting. When the drawing was laid in, I then began blocking in all of the most basic colors and values.

The paint was thin (thinned using Liquin at this stage). I scrubbed in my darkest values first, working back to my lightest values from there. At this stage, nothing was quite as dark, or as light, as it would be in the finished painting.

For this part of the process, I typically use only one or two different-size brushes, and I always use a brush that is just large enough to make me ever-so-slightly uncomfortable.

Step 3

I let the block-in dry to the touch (usually dries overnight), and I then began the process of dialing in the rest of the painting. I generally worked top to bottom, back to front. I also coated the canvas in a very thin wash of linseed oil before I began.

This process of “oiling in” allowed me to work in a similar way one might work wet-into-wet but without the worry of pulling color from underneath and muddying the fresh strokes.

Step 4

I continued working my way down the canvas over the course of about two weeks. The paint was getting thicker, the values more subtle, the edges were being established, and the color and color temperatures were all being carefully considered throughout this part of the process.

A note about the brushwork: As I work, as many artists do, I follow the forms in my painting with my brushstrokes. But there is also something else I’m considering in my brushwork: How does it play with the light? When I create a painting, I enjoy creating an impasto in areas that are lighter and then thinning the paint as it moves into shadow, but the brushwork and knife-work I use to create this impasto must also work with the light striking the painting.

I find I can create interesting effects with the brushwork that increase the painting’s richness and can be discovered when the painting is properly lighted (like in a gallery or museum). All of these effects of the light can add dimension to the work, color clarity and other subtleties that enhance the viewer’s experience with the painting. Changing the angle of the brushstrokes and knife strokes, as they relate to the angle of the light striking the painting, can have enormous impact on the visual aesthetic of the work.

Step 5

Once the painting looked nearly complete, I let it dry to the touch. This final stage in the painting process was where I added the thickest layer of paint, the darkest darks and the lightest lights.

I also made any final, minor adjustments in color and value where necessary. I also “oiled in” to areas that had dried flat or dull. Doing this returned those areas back to their original richness and allowed me to make adjustments to those areas.

My Painting Materials

My oil painting palette is fairly simple. It consists of Titanium White, Yellow Ochre, Cad. Yellow, Cad. Red, Alizarin Crimson, Burnt Sienna, Ultramarine Blue and Viridian. I also keep a few supplemental colors for use when necessary. They are Cobalt Blue, Prussian Blue, Phalo Green and Sap Green.

I use bristle flats and bristle-blend flats of various sizes, and I generally paint on #66 Claessens Linen mounted to ½ in. Gatorboard for anything over 12 x 16 in. For anything under that size I use the same linen mounted to birchwood panels.

ABOUT THE ARTIST

In February of 2002, Dustin Van Wechel left a successful 8-year career in the advertising industry to pursue his life-long passion, fine art, full-time. Since then, Dustin has earned numerous distinctions including the 2018 People’s Choice Award and the 2015 Premier Platinum Award at the Buffalo Bill Show, the 2015 Bob Kuhn Award for Wildlife at the Masters of the American West Show, the Wildlife Award and Teton Lodge Company Award at the 2006 Arts for the Parks competition. He’s also been featured in several leading art publications such as Art of the West, Western Art Collector Magazine, Southwest Art, The Artist’s Magazine, The Pastel Journal, and Drawing Magazine.

His work has been exhibited all throughout the U.S., in one-man shows, major art exhibitions and museums including the Autry National Center, the National Museum of Wildlife Art, the Buffalo Bill Historical Center, the Booth Museum, and the National Cowboy and Western Heritage Museum.

Dustin’s work is represented by Trailside Galleries in Jackson, Wyoming. He and his wife, Yvonne, currently reside in Colorado Springs, CO.

Connect with Dustin Van Wechel:

Website | Instagram | Art Workshop on how to paint wildlife

Related Article by Dustin Van Wechel: