Consider these equations as a starting point to help answer what you want and need to understand as an artist.

Analyzing Creative Responses

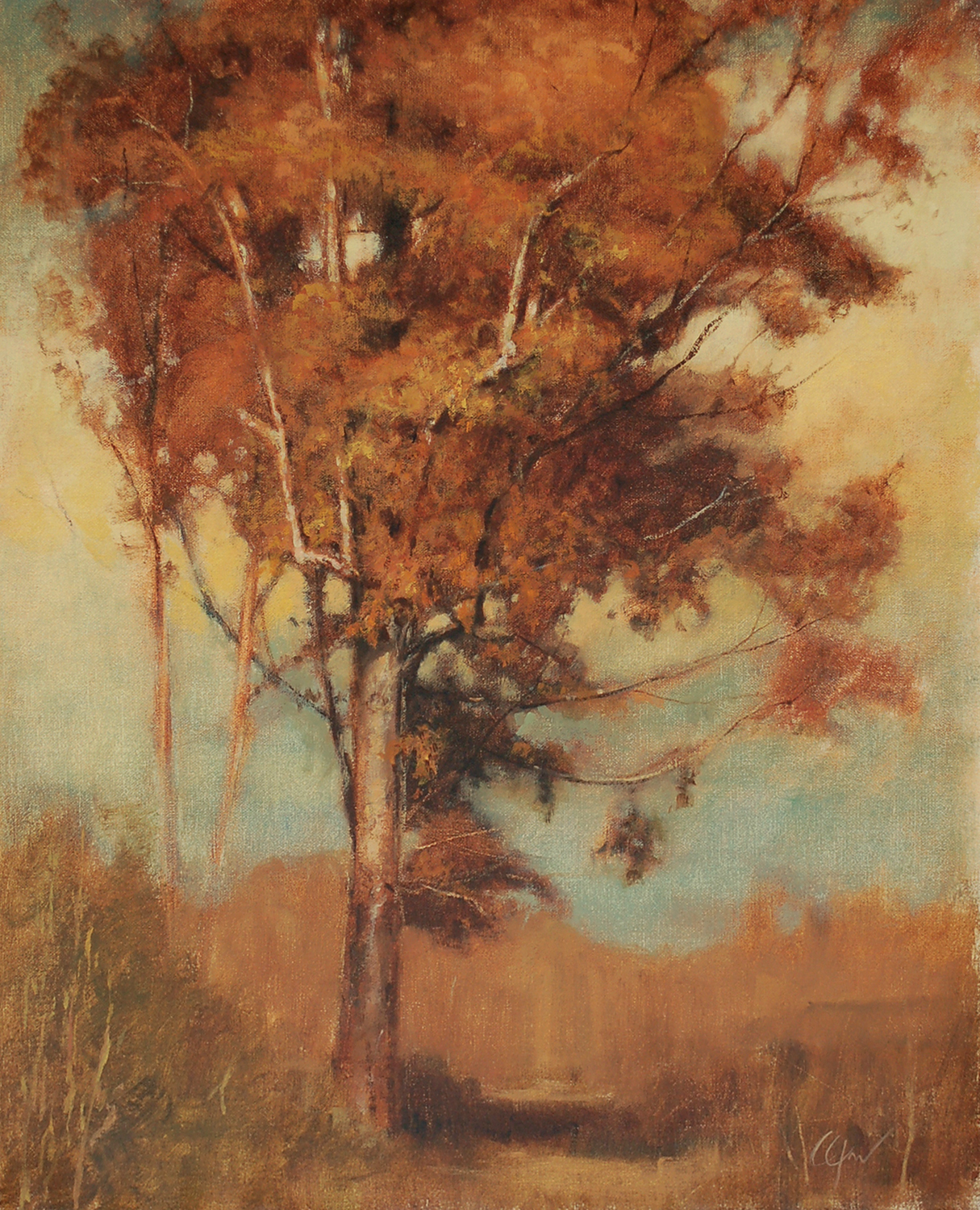

by Chris Groves

chrisgrovesstudio.com

I am here; not necessarily to solve a problem, but to create a piece of art that is a direct response to a set of intricacies; based on my current proficiency and understanding of materials, in addition to the comprehension of that which has been created before me.

Question: Can I come up with a logical (left brain) equation that would define a creative (right brain) response?

With painting, I like to think in terms of opposites. Warm to cool, big to small, lost to found, the list is endless. So in looking at “creativity,” I want to try to use an opposing language to help define such a limitless subject. Specifically, I’m trying to answer some important questions: Can I narrow down key elements artists must possess in order to create on a high level? What is necessary in order to create an “original” piece of art? How does one continually improve or grow?

To develop an equation for the creative process, we must first determine what our answer will be. Our answer is the finished painting, but what does that piece represent or communicate? Does it communicate a solution to a problem? We must remember that art is not an end-all solution, but merely one artist’s own “response” to something. That response is not necessarily correct or incorrect but is instead merely a personal view or appraisal of something. So we must not say we are trying to solve a problem, but only that we are “responding” to something.

I can start to develop the equation as:

x + y + z + . . . = A creative response to a problem

What are the basic elements that go into making art? Physically, we have the raw materials, the tools of the trade, charcoal, canvas, oil, brushes, etc. Yet, without the understanding and the skills to apply, the materials are useless.

Ingredient one – Skill (competence and experience) with materials and all things associated with their use, giving us:

x + y + Skill = A creative response to a problem

Skills are obtained through many avenues: self-teaching, art institutions, ateliers, instructors, etc. But it is the constant, repetitive, and long-term dedication of the artist that is required for these skills to be truly obtained.

A word on motivation: People are always striving to be in balance, to have things in a position of understanding and comfort (both shoes tied, clothes cleaned, emails returned). It is human nature. When things are out of balance, we work hard to get them back into equilibrium, or into a place that makes us feel complete.

This effort to get things back on track is what I see as “motivation.” Hard work being fueled by motivation is a primary element to becoming a successful artist. When I analyze the variable of “skill,” without motivation, one can only go so far. By making ourselves learn a new skill or a new technique, we are thrown “out-of-balance,” and we will feel balanced once again only when we have a good grasp of that particular technique or skill. The more we challenge ourselves to new ways of “doing,” the more we learn, the more we improve, and the more we lean on “motivation” to get us through to the next level.

We have skills and some materials, now what? We need to tell our brain how to combine these materials in a way that will create something that we don’t already have. A mark on a canvas, a color mixed, a form, a shape, something “new.” Again, these are all useless unless we have an idea or thought behind this collaboration of materials. Most importantly, that thought or idea must be something new, something that has not been done before, or it will not be considered creating—it will merely be a copy, an imitation, or a reproduction of an original thought.

How can an idea that is “new” come into being? An artist’s skill must become automatic and second nature in order for him to infuse his own imagination, and only then will he be able to achieve his own voice. But ideas don’t just hit you on the head, and it’s useless to wait around for “inspiration” to come to you. For me, everything comes out of constant work. Every time I paint for a show, and even after I have already planned out every piece that will go into that show, I come up with other ideas of pieces I could have painted. The thoughts and ideas that come out during “focused” work are tenfold those that came before. Ideas create ideas, but you have to put yourself in that position for that to happen, through the process of constant, focused work.

Ingredient Two – A Concept.

“Concept” is defined as a “thought” that seems complete, individual (original), recent, or somewhat intricate, giving us:

x + Idea (concept) + Skill = A creative response to a problem

I now have an original idea, and skills with materials. What else? Can I just go ahead and respond to a problem with what I have? How do I know it’s original? How have others responded to a problem similar to the one I am dealing with? Do I have to reinvent the wheel? Can I use what others know, and expand on that knowledge to get to my own response? Do I agree in part or in whole, with the response of others? Can I formulate my own response in support or opposition to what others have done?

Ingredient Three – Creative responses, ideas, and skills presented to us by those that came before.

Now the equation reads: What has come before + Idea (concept) + Skill = Creative response

Or, to put it more personally: What I know of “All that has come before me” + “my” current skill set + “my” idea = “my” creative response to a problem

I can now look at this equation and see what an artist can do to continually improve or grow. By developing the first two variables (understanding what has come before and my skill set), the final response should improve. When your abilities exceed your knowledge, you stop progressing. There is really no reason for you to stop learning about any aspect of art, because of the endless information that exists of past (and present) artists.

When I began to paint, my instructor asked me to pick one living and one deceased artist I liked, and about whom I wanted to learn more. I bought a book about each artist. Not only did this start my collection of books, but it also began my art research. I found that one artist leads to the next, whether it was that artist’s friend, his instructor, his student, or someone who used a similar palette.

My research revealed an incredible, endless linear connection. This, of course, led me to not only see their art in books, but to see it in person at museums, galleries, and exhibitions all over the world. This endless consumption of knowledge is bigger than all of us. I think that the visual connection at museums is one of the strongest reasons for the improvement in my painting. The past holds the key to what we do in the future.

This equation is a starting point to help answer only a tiny segment of what I want and need to understand as an artist. I am constantly asking myself questions, and I rarely have immediate answers, but the questions always send me down a road that ends in a deeper understanding of what I am doing with this profession.

Artists should always ask themselves, “What is the purpose of creating art? What is the purpose of this particular piece of art I am trying to create?” Too many artists get into the routine of creating for the purpose of selling and painting to the market. They paint what they think will sell, with no real purpose behind their efforts. As someone has said, “Don’t paint to sell, sell to paint.”

I think one of the reasons for creating art is to satisfy our need to communicate. The other reason is to evoke an emotion, or spark a response, as well as give the viewer an experience. I can’t predict what that response will be from any particular viewer, and chances are it will be different for everyone. Just as long as there is some kind of response, the communication will have begun.

Visit EricRhoads.com (Publisher of Realism Today) to learn about opportunities for artists and art collectors, including Art Retreats – International Art Trips – Art Conventions – Art Workshops (in person and online, including Realism Live) – And More!