On classical painting > Discover what the classical tradition means to master artist Daniel Graves, including the question he continually asks himself while painting.

By Peter Trippi

Editor-in-Chief, Fine Art Connoisseur

Some artists can be admired and understood almost entirely through their work, with scant reference to their training or worldview. This fact does not diminish their achievements, but it has not generally applied to Daniel Graves (b. 1949). Although he makes superb art and conducts a solo career, Graves cannot be considered apart from his life’s work — founding and directing the Florence Academy of Art (FAA).

Situated in one of the world’s most cultured cities, the FAA was founded by Graves in 1991 to train artists coming from around the globe in the time-tested materials and techniques of figurative realism. He also wanted them to absorb the academic priorities of beauty, storytelling, and craftsmanship — taught in ateliers and academies throughout the West until the mid-20th century, and passed on to Graves (against all odds) by his own instructors.

A LONG AND WINDING ROAD

Graves graduated with honors in 1972 from Baltimore’s Maryland Institute College of Art, where he studied anatomy and painting with Joseph Sheppard and Frank Russell. Although laissez-faire modernist art education was in full cry in the late ’60s and early ’70s, Baltimoreans have always made room for more traditional practice, and so Graves left the city well equipped to pursue history painting and etching with Richard Serrin at Florence’s Villa Schifanoia Graduate School of Fine Art in 1972–73. Through Serrin’s passion for Rembrandt, the young man learned to “read” a painting for both its technical characteristics and for what it reveals of its maker.

Graves moved on to Minneapolis, where a year in the atelier of Richard Lack (1975–76) connected him to the small and still-thriving circle of classical realists who trace their lineage — through Lack and his teacher Ives Gammell — back to Jean-Léon Gérôme and Paris’s Ecole des Beaux-Arts.

The lure of Florence remained, however, so Graves returned there for good in 1978. He began working under Nerina Simi, whose own father had studied with Gérôme, and he soon became friendly with Pietro Annigoni, who had, among other accomplishments, astonished the world in 1954 and 1969 with the relative conservatism of his classically painted portraits of Queen Elizabeth II. By 33 Graves felt he knew enough to open, with his compatriot Charles H. Cecil (b. 1945), a Florentine teaching atelier, which they operated together until 1990.

In 1991, Graves created the Florence Academy of Art, the official name of which contains the phrase “for the Training of the Professional Realist Painter and Sculptor.” Today the Academy thrives in a large former factory it has refurbished for its own use, and also operates branches in Jersey City (near New York City) and Mölndal, Sweden.

As a young man, Graves could see that the academic priorities of beauty, the human body, storytelling, and craftsmanship — once taught in ateliers and academies across the West — were passé. Thus he and his friends, as he puts it, “looked for the frayed threads of the realist tradition, desperately wanting to feel connected to it. Because I picked up pieces of the tradition from many different people, what we teach now is a blend of what I received myself. I have necessarily interpreted their teachings in my own way, fitting the pieces together as seemed most right.”

Graves believes that humanity and beauty have always been expressed through the very craft of painting, through the selection of specific materials that allow the artist to attain truly expressive qualities. For this reason, he uses traditional techniques such as grinding his own paints, cleaning his own linseed oils, making his own varnish, and stretching and preparing his own canvases.

The Academy’s painting curriculum, with its intensive observation of nature and the Old Masters, reflects Graves’s own artistic practice. Ideally, a talented matriculant will spend three or four years with Graves and his fellow teachers. (Thinking not only of art but also of culture, he notes that one must “give Europe some time to sink in.”) Graves has broken “the vastly complex task of learning to draw, paint, and sculpt from life into gradual steps”: students first draw from classical casts (three dozen of which were obtained from the Venetian studio of the 19th-century Spanish master Mariano Fortuny), and also from the live model. In Florence, where Renaissance humanists’ prioritization of the body re-energized Western culture in the 15th century, to draw from the live model is a particularly thrilling act.

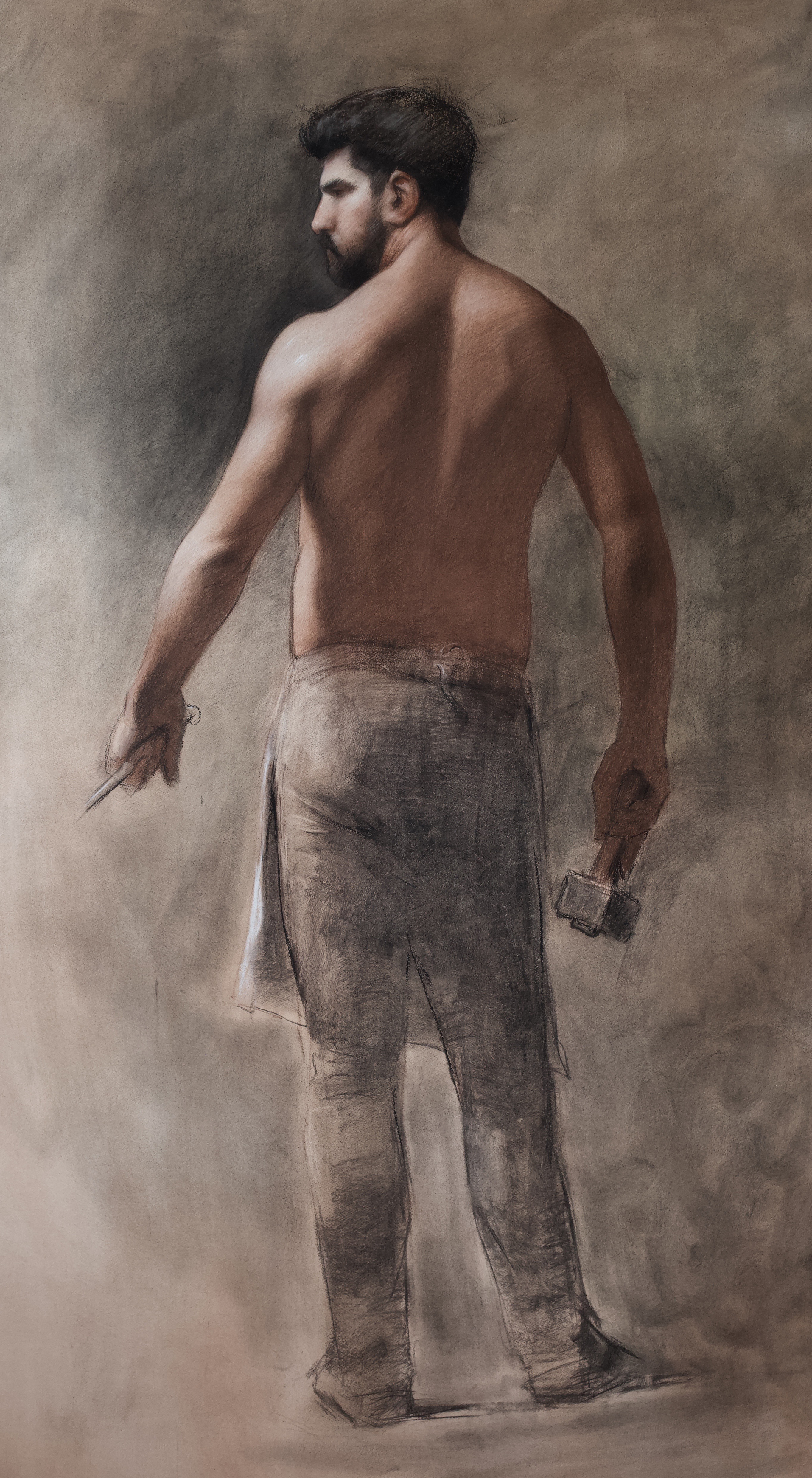

Painting students next learn to use precise values in charcoal, graphite, and chalk, then in oils (first in grisaille and then colors); their sculptor counterparts focus on creating correct structures in clay. In contrast to much art education today, where students may drift without meaningful guidance, Academy pupils are critiqued regularly to ensure they are on course, and to give them personalized suggestions on how to improve.

THE BIGGER PICTURE

“The values of beauty and meaning are slipping away,” Graves warns. “We need to be reminded that these things are still important. In the classical tradition, the Intellect, a sense of Justice, and the Heart develop within people as they mature. It is through these values that the artist strives to contribute his or her vision of the world in a way that elevates society. Being a part of the classical tradition is a calling to do something good for others.”

Graves continues, “John Ruskin once said, ‘All great art is in praise of something we love.’ This is one of the most important concepts for an artist to contemplate. It calls us to consider, wisely, the significance of why we are doing what we are doing — our intent. It is through our humanistic connection between the subject matter and what we paint that this intent is made visible. The painting then becomes an open dialogue between artist and viewer. When you connect with this tradition, your voice becomes part of the ongoing dialogue, which is the Continuum. Learning the classical techniques opens the door to express, through our chosen medium, what matters most to us. We reflect upon questions like, ‘What is it to be human? What are our values? What makes us aspire to be a better person?’”

Graves is happy to cite a successful example of this approach: “When we look into the eyes of a Rembrandt self-portrait, how much closer can we get to knowing the soul of another human being? Rembrandt’s hands mixed the paint we see, but what is actually before us is a blend of his image with ours and that of every human. There is no substitute for this experience.”

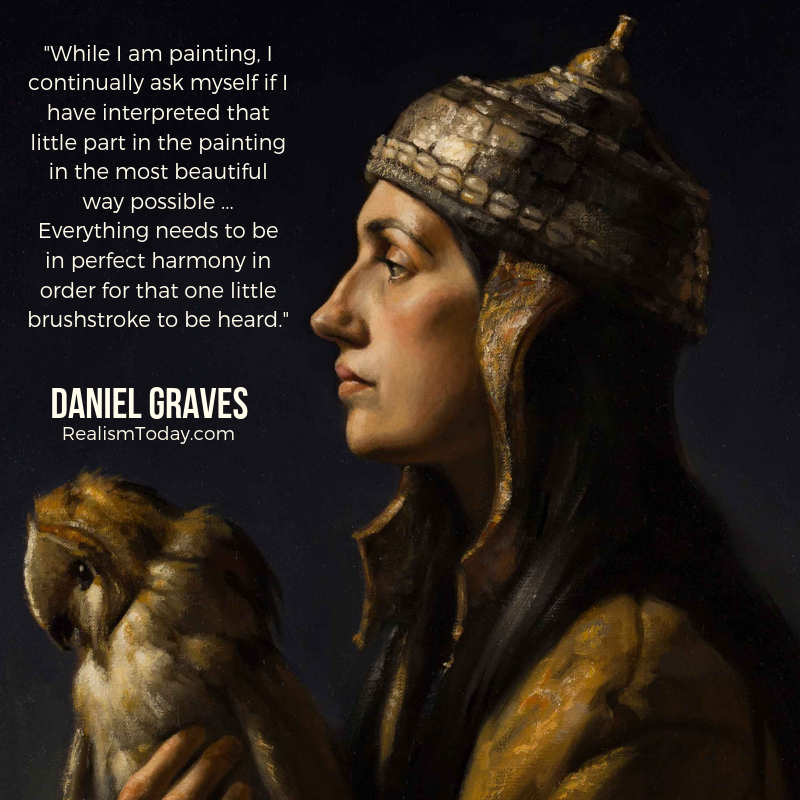

Graves explains, “While I am painting, I continually ask myself if I have interpreted that little part in the painting in the most beautiful way possible. Does that gesture say what I want it to say? Does the composition create the sensation I want to share? Everything needs to be in perfect harmony in order for that one little brushstroke to be heard. This is very similar to listening to classical music — all parts of the orchestra must be in perfect harmony with each other, almost fall away from the forefront, in order for that apex moment to be heard. This is the language of painting, the sharing of my view of the world with others.”

Article reprinted with permission from Fine Art Connoisseur magazine

***

DISCOVER THE SECRETS OF OLD WORLD PORTRAITURE

For decades Daniel Graves has been teaching the ancient techniques of the Old Masters at the school he founded in Florence. The Florence Academy is among the top schools in the world for representational art, following the traditional atelier system of study created generations ago by the world’s leading artists.

With “Portraiture with Daniel Graves,” a cinematic art video workshop, you’ll learn:

• How to grind your own paint and create painting medium

• How to draw from a live model

• How to complete an underpainting

• Techniques for creating skin tones from a three-color palette, and more.

Click here to learn more about “Portraiture with Daniel Graves.”

I had the pleasure of meeting Daniel while living in Minneapolis. At that time I had been working with Richard Serrin,as a model for a series of paintings he was doing for the United Lutheran Churches.

To this day I still believe that Daniel was one of the finest men I have ever had the blessing of knowing.

At that time Daniel had given me some of his etchings,so that I might sell them for him. Much to my dismay my car was broken into and every piece of art I carried wasn’t stolen as a normal thief might have done,but rather everything that even resembled art was literally destroyed,torn to shreds. In my shame that I was somehow the reason for this senseless destruction I lost contact with Daniel. To this day I regret not going to him to explain what had happened,and to this day I carry a guilt for not doing that.

Not only one of the finest artists I have ever met, but more notably one of the finest,most pure individuals I know that I will ever meet.

Comments are closed.