The following essay on color theory is an excerpt from Todd Casey’s popular book, The Art of Still Life: A Contemporary Guide to Classical Techniques, Composition, and Painting in Oil.

Color “Rules” That Aren’t True

BY TODD CASEY

There are a number of “rules” about how color should be used that aren’t true—or aren’t always true. For instance, you might have heard that if you have warm light you should have cool shadow and vice versa. Yes, this is a common formula, but you shouldn’t just follow formulas. Instead, you should observe what’s in front of you. If an object is in warm light and does have a cool shadow, paint it that way, but if it doesn’t, don’t. Of course, you may make a stylistic choice to follow the so-called rule, but then you have to admit that you’re taking the liberty not to paint what you see.

Another untrue “rule” is that you should never use black out of a tube—that you should mix your blacks yourself. The principle of mixing your own blacks originated with Impressionism. It relates more to painting out in nature, where there is a lot of color in shadows because of ambient light.

But there is nothing wrong with using black straight out of the tube. Artists like John Singer Sargent, James McNeill Whistler, and Winslow Homer used black quite often in their paintings. The most important thing about black is its value. It is all but impossible to mix a color with the same dark value as black. If you think of black as just its value, you’ll use it in the correct places, like crevice shadows.

What is Local Color?

When painting, it is important that you try to match colors to what you see and not to what you think you know. The term local color refers to the color that you actually perceive an object to be. If you were to paint a sphere cobalt blue, that would be the local color of the object. Local color can be seen most easily on matte surfaces as there is less glare from the light source affecting your perception.

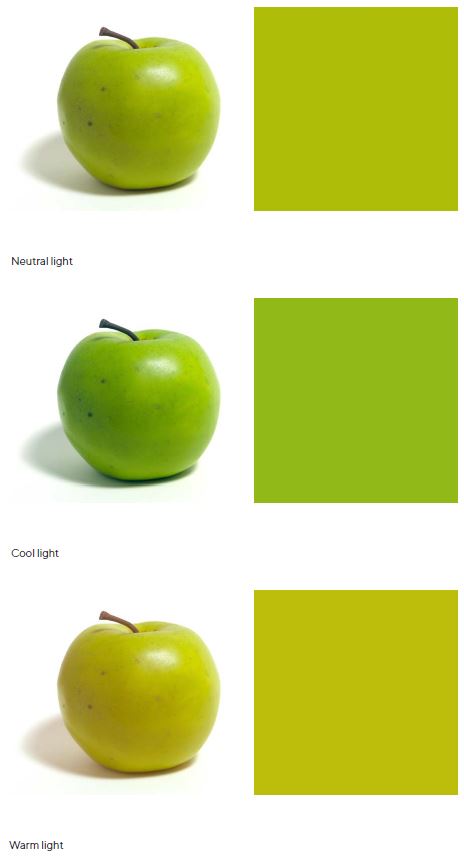

Light temperature partly determines how you perceive an object’s hue. The same green apple will not appear to have the same hue under a 3000 Kelvin light as under a 5500 Kelvin light. Here are photos of the same apple in three different lighting scenarios: neutral light, cool light, and warm light. Each looks to have a slightly different hue. Swatches of local color show the subtle shifts in hue.

To determine whether a color you’ve mixed matches the local color you perceive, load some of the color onto a palette knife and hold it up to the object. Hold it as close as you can to the setup to ensure the hue isn’t affected by light falloff, which may make your color matching inaccurate:

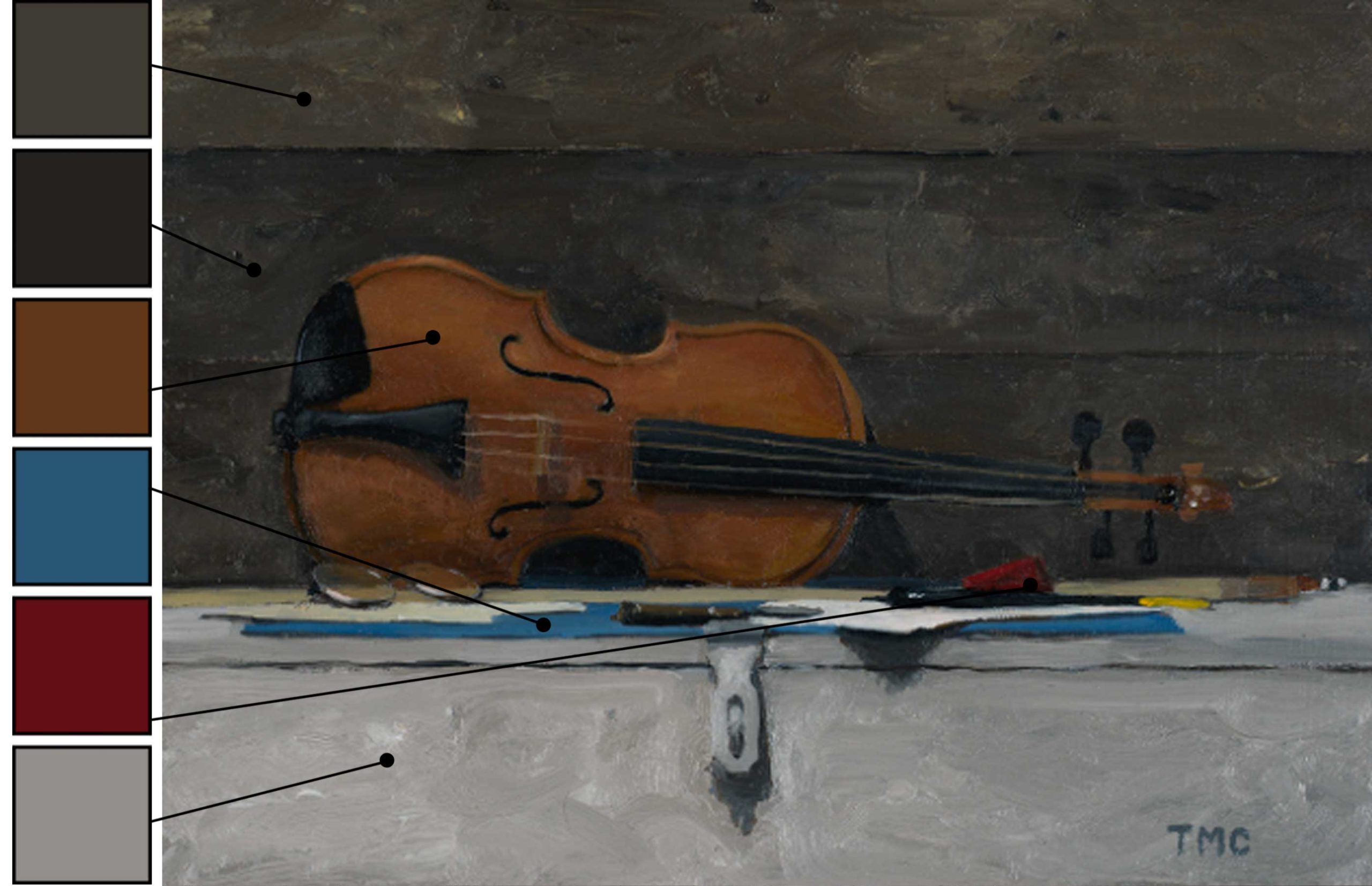

Different kinds of light shift the color and change the mood of a setup. At center is a poster study for my painting “Another Story,” (below) done in cool light. The final painting, bottom, was done in a warmer light. The swatches show the subtle shifts of color in relation to the light.

Bonus Tip for Color Mixing: It’s preferable to mix your colors on your palette, not on your painting surface. One of the best ways to do this is to mix with a palette knife on a glass palette. Placing a neutral gray paper beneath the palette, as shown below, can help you see the hues clearly. (You might also place a value scale beneath the glass to help you gauge the values of the colors you’re mixing.) Glass palettes have the additional advantage of being very easy to clean.

Watch Eric Rhoads interview Todd Casey during a recent Facebook Live event:

Related Article > Art Studio Lighting Basics by Todd Casey

- Visit PaintTube.tv to learn how to paint portraits and figures in the style of contemporary realism, and much more.

- Join us for the next annual Realism Live virtual art conference and study with the world’s best realism artists.

- Become a Realism Today Ambassador for the chance to see your work featured in our newsletter, on our social media, and on this site.