Contemporary Realism Artist Joel Babb > “Imagine da Vinci and Seurat meet in a field in France. Do they actually see the same things?”

Joel Babb: Town & Country

By Thomas Connors

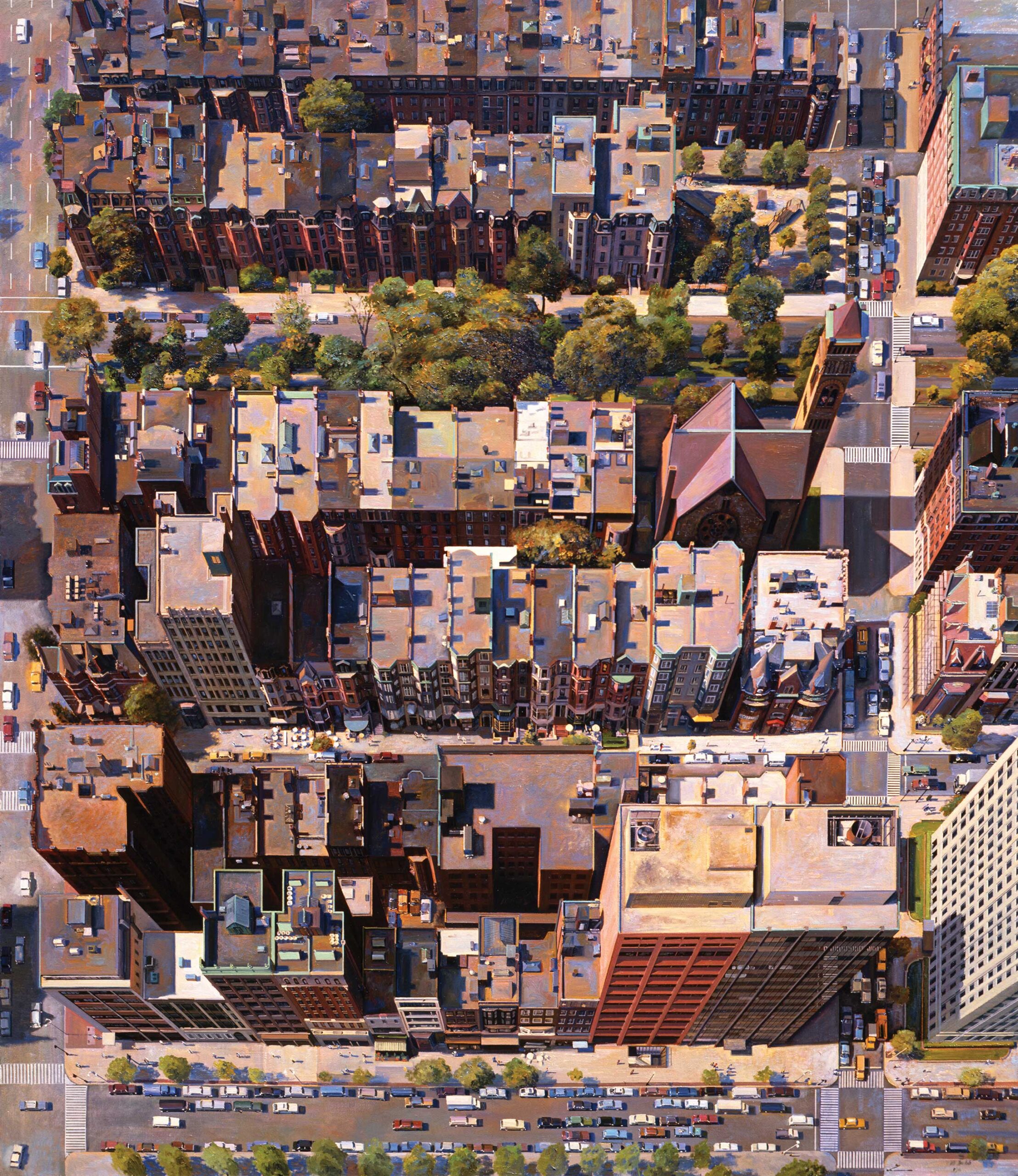

For all its red-brick charm, the city of Boston has not been represented on canvas nearly as much as have its leading citizens — think of Copley’s portrait of a pensive Paul Revere, or Sargent’s vision of the scandalously clad collector Isabella Stewart Gardner. With the exception of Childe Hassam, even members of the Boston School, who included Edmund C. Tarbell, Frank Benson, and William Paxton, rarely went out onto the street to paint. Yet the contemporary realism artist Joel Babb (b. 1947), whose work now springs from the backwoods of Maine, once made Boston both his home and his subject. The geometry of its built environment, particularly the 19th-century grid of the Back Bay neighborhood, proved endlessly appealing to the artist, for whom perspective has remained almost an idée fixe.

Babb was born in Georgia, raised in the Midwest, and is a New Englander by acclimatization, with an aesthetic sense formed by his sojourns abroad. It was in Italy, amid Old Masters and marble monuments, that he found his focus. His consciousness of art, though, began as a youth in Nebraska. “My uncle was an artist, and my mother idolized him and his works, and I did, too,” says Babb, whose own artworks are today in the collections of the Museum of Fine Arts, Boston, the Portland Museum of Art, and Maine’s Farnsworth Art Museum.

The notion of becoming an artist took hold, but Babb’s route to the studio was irregular. At Princeton University, he studied English and German and toyed with the idea of becoming an architect before settling on art history. He became fascinated with Chinese landscape painting thanks to courses taught by the noted scholar Wen Fong, who went on to chair the Metropolitan Museum of Art’s department of Asian art. The university’s studio art program was limited then, but Babb did take classes with George Ortman, the Californian perhaps best known for constructions and collages, and with the sculptor George Segal.

After graduation, Babb headed for Munich, where Princeton’s German department had secured him a temporary position in a bank. While there, he visited the city’s superb museums, taking in the masterworks of Rubens, Rembrandt, Titian, and Caspar David Friedrich. From Germany, Babb traveled to Florence and then Rome, where he marveled at the “incredible concentration of architecture, painting, and sculpture, all fused in the matrix of the Catholic Church.” He obtained reading privileges at the Bibliotheca Hertziana — the German institute for art history in Rome — where he discovered the landscape drawings of Claude Lorrain that would become his touchstones. “Lorrain’s drawings,” Babb declares, “are the best articulation of the basic structure of landscape, of how the sense of recession in the landscape occurs.”

Babb’s time abroad convinced him that he wanted to be an artist. “I had the ambition,” he claims, “but no real ability.” With a letter of recommendation from Segal, he applied to several graduate programs, finally choosing the School of the Museum of Fine Arts, Boston. To support himself, he took a job as a night watchman at the museum, carrying a sketchbook as he made his rounds of its empty galleries. While he loved being able to study great works so closely, Babb’s learning curve wasn’t easy. “There I was, a Princeton art historian, and I still didn’t know anything,” he recalls. “There was a whole language I had to get up to speed on.” While dismayed to realize that the Museum School pursued a fairly avant-garde ethos, Babb did respond to the “Color and Light” course taught by the photographer-turned-painter T. Lux Feininger.

Soon after receiving his master’s degree in 1972, Babb became the teacher himself through a job in the museum’s education department. “For me, the mysteries of perception are at the root of what I enjoy about painting, so I explained the course this way,” says Babb. “Imagine Leonardo da Vinci and Georges Seurat meet in a field in France. Do they actually see the same things? Do they actually see the same way? The biological perceptual system — is it identical? If it is, then why did they paint so differently? I think it’s fascinating to think about.”

In his own art, Babb was diving deeper and deeper into an exploitation of perspective. “I had drawn Roman church facades and had become familiar with the vedutisti of Venice. I had studied the great Renaissance architect Leon Battista Aberti. There was a fabulous exhibition of Canaletto at the Met in New York that got me enthused about doing view paintings. Would I be able to make a Boston street scene with the same qualities? That was the challenge.”

Are you a contemporary realism artist?

Become a Realism Today Ambassador for the chance to see your work featured in our newsletter, on our social media, and on this contemporary realism site.