Contemporary Realism Still Life > Scott Fraser address the challenges of being a realist painter trying to create something new and relevant in the 21st century.

The Still Life: On Lemons and Art History

BY SCOTT FRASER

I am a painter who lives and works in Longmont CO, where the sun shines 300 days a year. I have a short commute down the hall to my north-lit studio where I paint my still life set-ups directly from life. Here, the large windows let in that big blue Colorado sky, which contributes luminosity to my work. I enjoy visits from my wife and kids, or my dog Petunia, who likes to lie on the nearby heating vent.

Although I have worked in a variety of mediums and genres over the years, for a long time now my focus has been on still life, because it has contained my interest and has such a breadth of scope for subject matter. Much of the still life work I do has a connection to art history. A number of my pieces address the challenges of being a realist painter trying to create something new and relevant in the 21st century. Sometimes I do this humorously, and sometimes seriously. Anything is fair game.

One of my favorite paintings is Quince, Cabbage, Melon and Cucumber (1602) by Juan Sánchez Cotán, a 17th century Spanish artist I greatly admire, who has influenced me along with countless other artists. Because of its compositional and elusive mystery this painting is considered by many to be one of the greatest still lifes ever created. I have seen the work in person several times, most recently in its permanent home at the San Diego Museum of Art.

I love the effect of the square within a square, which frames the curve made by carefully placed fruit and vegetables hung from strings. For all its impact, it is a very minimal work.

You can see how I borrowed from this composition in my painting “Catenary Curve.”

Described as “the curve that a hanging chain or cable assumes under its own weight when supported only at its ends,” the catenary is explored at length in the work of Jasper Johns, another artist whom I admire greatly. He thought the curve was so intriguing that he created a series of over 70 paintings, drawings, and prints that dealt with this compositional device to which he felt the human eye was subliminally drawn. One of our country’s most iconic monuments, the Gateway Arch in St Louis, is an inverted catenary. Another stunning catenary landmark is the Golden Gate Bridge.

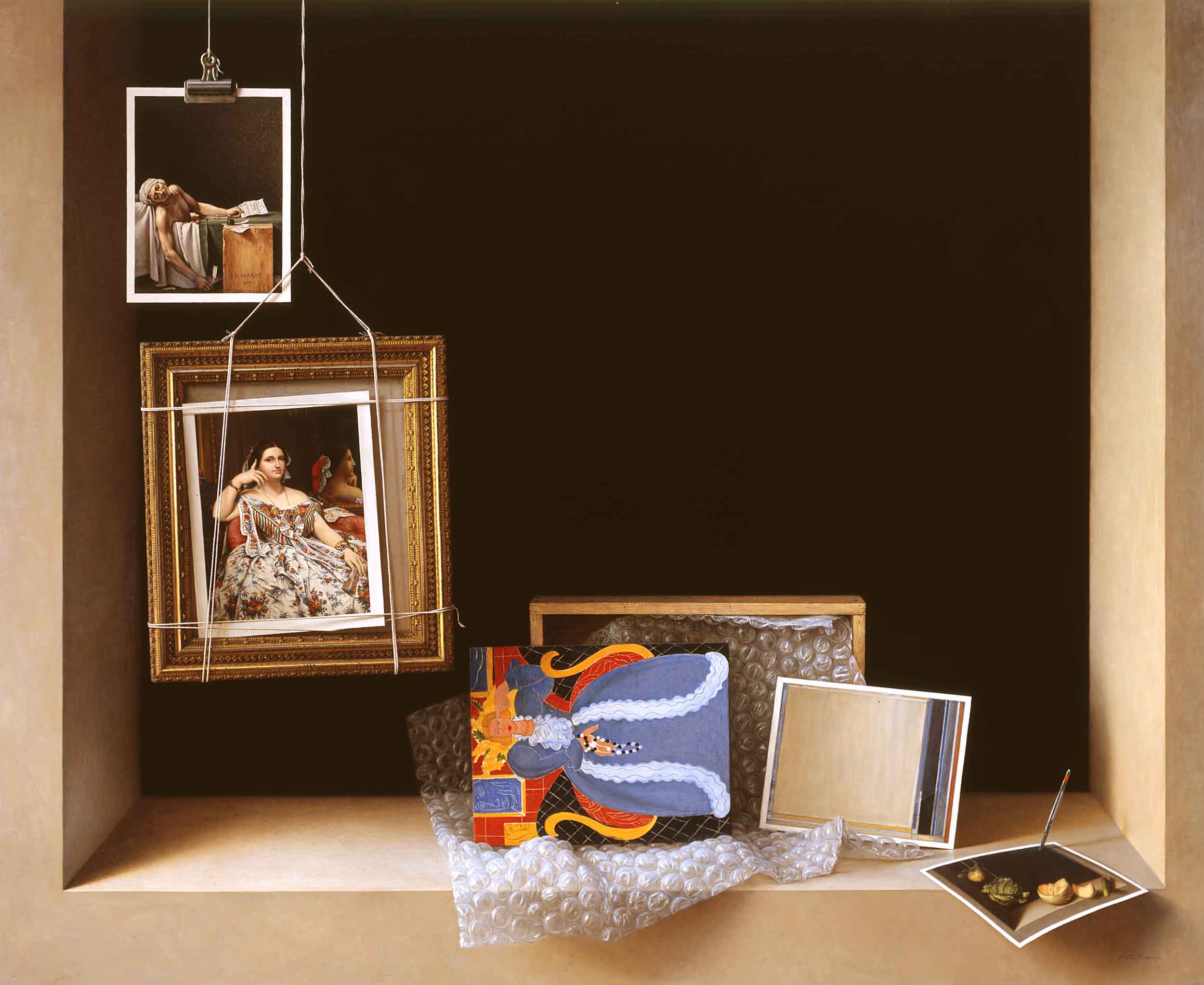

In “Catenary Curve” I applied the structure of “Quince, Cabbage, Melon and Cucumber” to an art historical time line, using Jacques Louis David’s Death of Marat as the starting point. Each painting in the work relates back to the David, as you can read in this linked description of my painting. “Catenary Curve” is a large painting, now in a private collection, and the pre-study painting is in the collection of the San Diego Museum of Art, where it resides with the original Cotán, which is a great honor.

This all sounds kind of heavy and we artists can get so caught up in the underpinnings of concept, we forget that there should be some delight attached to the work. This is where my peel series comes in. A few years ago I had a little fun referencing Dutch painters of the 17th century, such as Willem Kalf and Pieter Claesz, who used a partially peeled lemon as a motif in their still lifes.

Contemporary painters still use this luscious visual conceit. I decided to exaggerate the effect by extending the lemon peel to extreme lengths, keeping the eye moving and creating a kind of surreal tension.

Taking things a step further, I envisioned a large painting that would include numerous peeled lemons of different lengths composed to incorporate an organic catenary curve, residing in a mysterious dark niche à la Cotán. Instead of fruit hanging from a string, this fruit was itself the string. I did a number of pre-studies leading up to the large painting, including a small color study in oil and two large drawings that worked out the mechanics of the top and bottom sections. While in the pre-study stage, a viewer commented that the piece brought to mind falling water, hence the title “Lemon Fall.”

Often I revisit an idea over a series of works, as demonstrated in my sequence of lemon peel paintings and my succession of images that include the dark niche setting as influenced by Cotán, and my series of Catenaries. “Lemon Fall” is a culmination of all three. It was the cornerstone of my 2015 solo show at Quidley & Company in Nantucket.

Another of my major paintings with art historical references is “Reign.” This is a humorous take on how I perceive my work in the present-day art world. When I was composing “Reign,” I had been reflecting a lot on the fact that the Armory show was celebrating its 100th anniversary, and so much of the work being done today is an awful lot like what was going on back in 1913. I was feeling as if the art world had been caught in a loop, but this time with a lot of money thrown in.

Don’t get me wrong—I am not criticizing modernism. I was immersed in it in art school and I embraced its many “isms” and offshoots. You only have to look at my work to see where my sensibilities lie. What I don’t care for is its one-sided dominance and the system that props it up for an elite few.

“Reign” addresses this “art about art” topic. The painting contains two still lifes—one under the table and one on top. Some of my more iconic objects are sheltered underneath with a more classical arrangement being rearranged, so to speak, by modernism’s critical reign above. I have highlighted it here because it was a challenging piece to work on. I learned a great deal, both in technique and substance on the eight-month journey towards its completion.

I have been lucky enough to make a living doing what I love since 1980, and I find it invaluable looking at and trying to understand both contemporary artists and artists of the past. There is always something out there to inspire, and by borrowing and synthesizing, I can create something new using my own voice that can carry forward into the future.

Learn more about Scott Fraser at: www.sfraser.com

Related Article by Scott Fraser > 20 Earthly Delights – Contemporary Realism Still Lifes

Learn how to paint still life, including how to find the right color palette, the step-by-step process of creating a composition, and much more with the art video workshop “Daniela Astone: Creating an Elegant Still Life.”

Though Daniela Astone started her art education on a typical track, her passion eventually landed her acceptance into the Florence Academy. She went through the entire program, but, unlike those who graduated and moved on, she wanted to carry that program on to future generations. So she was trained personally by the instructors at the school, including Daniel Graves.

Preview her contemporary realism art video workshop, “Creating an Elegant Still Life,” below: