Contemporary Sculpture > Olivia Kim explains how she cross-links various art practices with anatomy, biomechanics, biokinetics, neuromuscular science, optics and physical training.

BY OLIVIA KIM

Regardless of age, culture or sex, we exist in organic bodies that constantly move. There is a notable perception gap in the arts since still poses that aesthetically suggest motion are commonly used as a replacement for actual body movement. Many years of figurative art studies taught me that there is a common observable phenomenon—it is unnatural for the human body to pose motionless for extended periods of time. Models suffer from fatigue due to the overuse of certain muscles to maintain a pose. This realization confounded me. I wanted to create work that reflected a total balance and respect for the model’s body and my own artistic expression. Consequently, I decided to capture body movement.

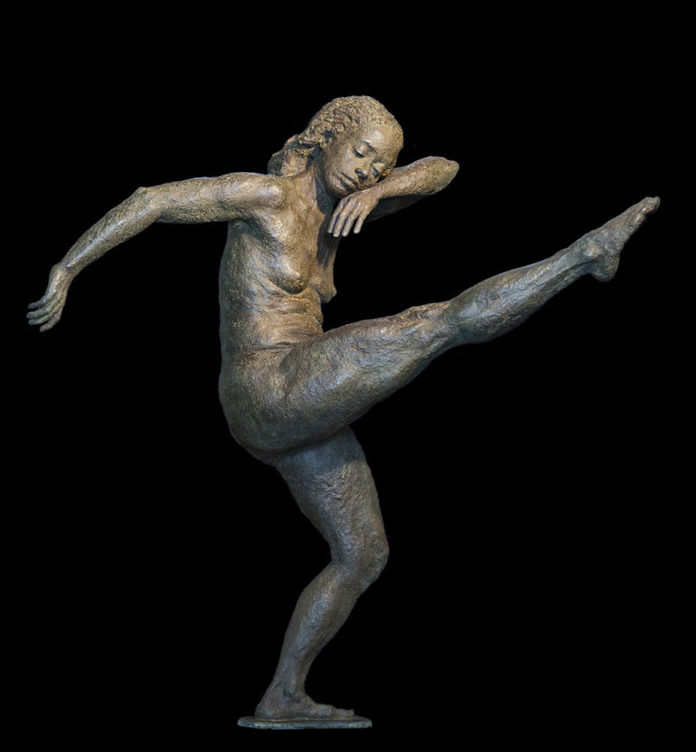

I have dedicated the past ten years to the study, experience and creation of sculptures of the body in motion. Understanding how to do this has been challenging and personally rewarding. I developed my own methods to perceive, analyze and coherently convey what happens as fast as a fraction of a second. I cross-link various art practices with anatomy, biomechanics, biokinetics, neuromuscular science, optics and physical training.

The models for my sculptures represent a range of body types and movement abilities. I have worked with older seasoned dancers from the Bessie and Tony Award-winning Garth Fagan Dance Company, dancers of Futurpointe Dance, as well as untrained everyday people.

Artmaking is only the tip of an iceberg. Expanding the range and depth of my perception has been the key to making interesting work in the art studio. I started by accessing my earliest nonverbal explorations of the world: touching, tasting, seeing and smelling. As a baby, sitting on a gritty cement porch, I felt how slippery onions were if the skins were loose. I recall the branches of lychee trees and the fragrant taste of the fruit the neighboring children collected.

A later memory was of the strange, absolute dark of my aunt’s house—my eyes were painfully blasted by the light outside, and then dizzied by the extreme blackness of her home. All I could see were the ghostly curtains, which were the only indications of light that I used to orient my body in space. Every experience was a new and unlabeled territory, unmediated by the confusing abstraction processes of complex verbal language.

These memories made me realize that an important key to understanding motion is paying attention to what my nonverbal senses were communicating all the time. For years, I was having a hard time making sense of movement, because our muscular and endocrine systems operate at a faster rate than cognitive thinking. I needed to feel changing nuances that would normally be ignored and left to subconscious processing. Combining the study of anatomy with intuitive feeling, I became aware of the spatial form of my bones and where muscles were placed over joints. As I moved around during the day, I paid attention to how it felt when muscles contracted or relaxed.

For the first years, my studies progressed slower than I preferred. At a certain point I learned this is due to our movement structure. We are bipeds, moving inefficiently the majority of the time, compared to four-legged animals. Just look at how a powerful gorilla moves with four limbs as opposed to their shakier movements on two legs. They are literally wobbling!

Our bodies suffer much physical stress because our limbs are constantly struggling to move in space without the grounding effect of being on all fours. The structural inefficiency of supporting our bodies on two legs is the cause of much confusion in the communication between the conscious mind and rest of the body. Because our movements are typically uncoordinated, my conscious mind had a hard time remembering the changing position of a moving person.

Each person deals with the problem of mechanical inefficiency in different ways. The common practice is to squeeze or hold our bodies rigidly in fixed points to control our movements. Sometimes it is necessary and helpful to do so, but not in excess. The problem with too much holding is that it can become a pattern that overworks limited areas of the body, which contributes to deterioration. Repetitive holding encourages the growth of muscle memories. A strong muscle memory pattern will get triggered repeatedly if you unconsciously move in a habitual way.

I make it a practice to categorize my observations as precisely as possible. I methodically isolate various factors associated with motion. Muscle tone, bone alignment, hydration, nutrition, emotional and mental states are some examples. Later on, I make comparisons when I encounter a similar gesture. This method has helped to grow an expanding lexicon of movement vocabulary.

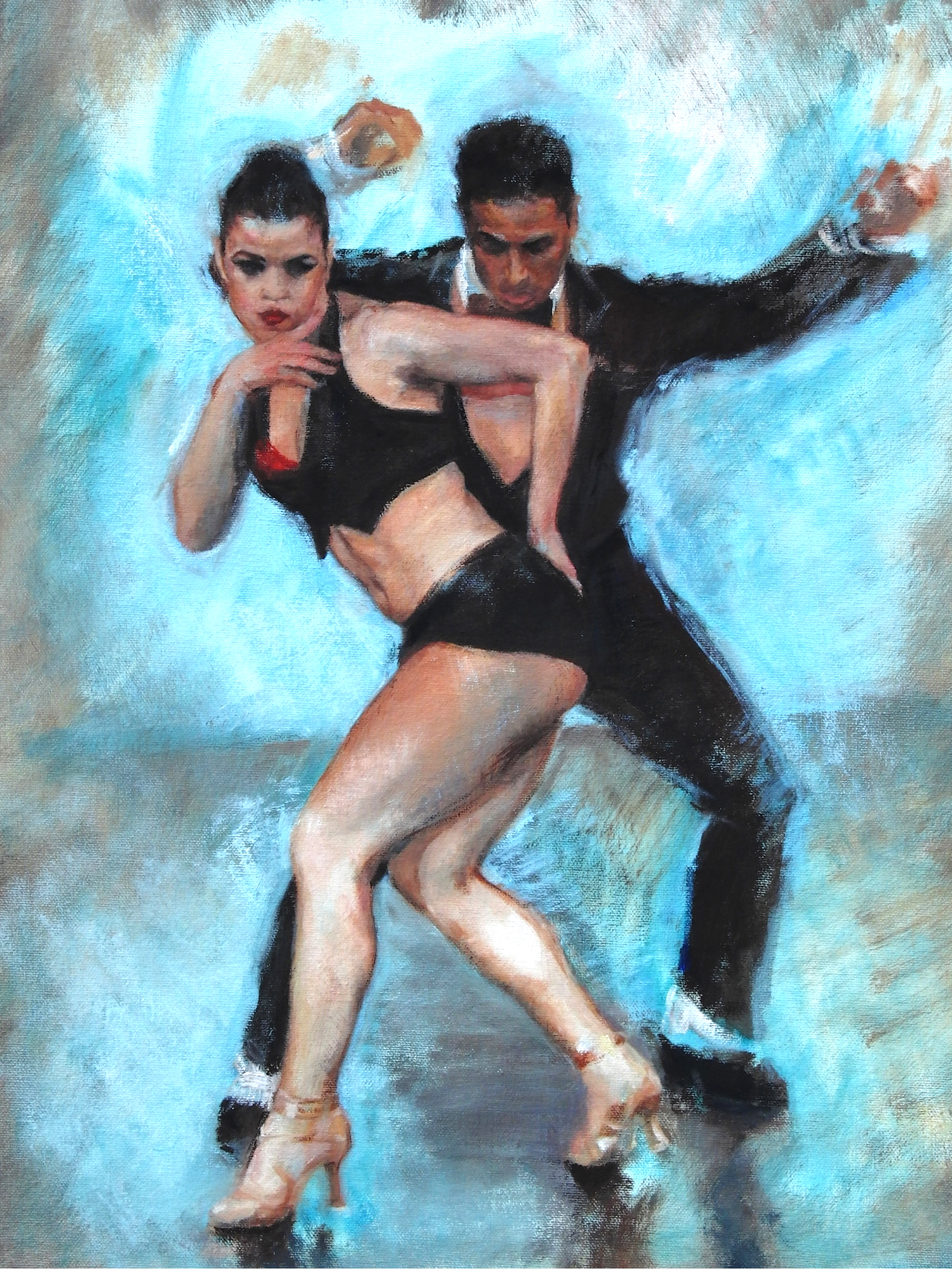

I spend a good amount of time doing various types of physical training along with creating in the studio. Typical gym machine workouts, yoga, Chi-Lel Qigong™ and world dances are a few examples. The past two years I have learned and/or practice seven different types of social and contemporary dance: Cuban salsa, samba, bachata, merengue, kizomba, Argentine tango and Garth Fagan Dance technique. The reason for such a range of movement styles has been to compare biomechanical (structural) and biokinetic (motion) dynamics.

In order to truly explore the possibilities of movement, I had to disrupt my habitual muscle memories by introducing new dynamics to my body. This is where social dances come into play. Since the dance occurs via the interaction of two people I found that structurally, it was one way to connect back to the ground. If you look at two salsa dancers, what do you see? Two people are making a body bridge—two pairs of feet on the floor, with the bridge meeting up through their hands and arms.

Related Article > How Drawing Influences My Sculptures

I use the body bridge structure to send pressure from my feet through my limbs to the next person. However that person responds is up to them. When they return the pressure back to me, I can move or manipulate the force according to my creative and mechanical needs. Having clear parameters for movement has been instrumental in coherently isolating specific joints in space.

Specific body movements are linked to psychological and emotional makeup. By manipulating the movements of a dance partner through my direction of pressure, I can affect their psychological/emotional state. The force and direction of my movement can make a partner feel stable and connected, or shaky and insecure to the point of anger.

At a certain point, as the range of my experiences grew, I finally noticed the ability to see and coherently understand split-second movement. I noted holding and release patterns and a plethora of other habits that I now equate to a person’s personality. People with rigid mindsets are more rigid in their movements. Highly adaptable people are quicker to adapt to changes. Some people listen more with their bodies by paying attention to the quality of pressure I deliver, and then respond directly to that. Others are more involved in maintaining their own movement patterns, and if I do not accommodate immediately, I can sense hesitation or even aggression as that person pushes harder to make me follow their movements.

Learning how to listen to my body has transformed my studio practice. While lifting heavy bags of raw materials for sculpture, I have a heightened ability to sense weight shift and prevent injuries. What used to be grueling repetitive motion is fun, because I can creatively explore how to obtain better mechanical advantage. My body is allowed to use different muscle groups simply by changing rhythm and positioning. I pay attention to feelings of fatigue, so I don’t cause damage to my internal organs through overworking. I observe how my conscious thoughts clearly cause changes in my body and vice versa. This helps me to focus on present-moment living and the creation of new work.

My response to pain has changed. I’m not as afraid to feel it. This has allowed me to find its cause in order to bring balance back to something that is not “feeling right.” Now when I feel pain, I recognize it as one of many types of nonverbal messages that my body is communicating to my conscious mind.

Working with diverse art mediums requires different sets of sense perceptions, motor skills, body mechanics and tools. Comparing the results of working with various materials produces a growing nexus of information that feeds my overall perception of the body. For example, painting in ink has helped me to develop photographic memory recall. Its fluid application requires less physical effort than pressing a drawing instrument onto paper to produce an image. Since it is a faster way to record visual memories, I get a better idea of how much information I remember.

Since sculpture can exist outdoors, and varying light sources affect our photoreceptors of the eye differently, it is necessary to study both gray scale and color perception. I use charcoal drawing to create gestural outlines and nuances of value changes to describe form. Since gray scale drawing calls upon the use of rod photoreceptors in the eye (the most abundant type of photoreceptor), it is easier to observe multitudes of gray values. Discerning among grays is a helpful crossover to analyzing shadows that are created by sculptural forms in monochrome clay.

Oil painting allows me to explore the phenomena of light falling on the body, and how atmosphere affects color qualities during movement. Since cone photoreceptors in the eye are less abundant, and function at higher amounts of light than rods, color study is only applicable for certain situations. The human eye will switch from seeing color to perceiving in gray scale at reduced light conditions.

Sculpture is a literal medium, in that it interacts directly with its surroundings. The illusion of atmosphere in painting cannot be duplicated the same way in sculpture. Unlike painting, sculpture involves the correlation of many viewpoints. Modeling clay requires a totally different body dynamic.

I have to move around the work to see how body parts fit together to create a unified gesture. I have to connect my own internal sense of body movement (proprioception) to what is happening in the sculpture. I feel which angles and velocities of movement create tension or relaxation in relation to the rest of the body. I use tactile, spatial and visual skills to produce outlines, internal structure and surface textures that convey a visual and spatial sense of time and speed.

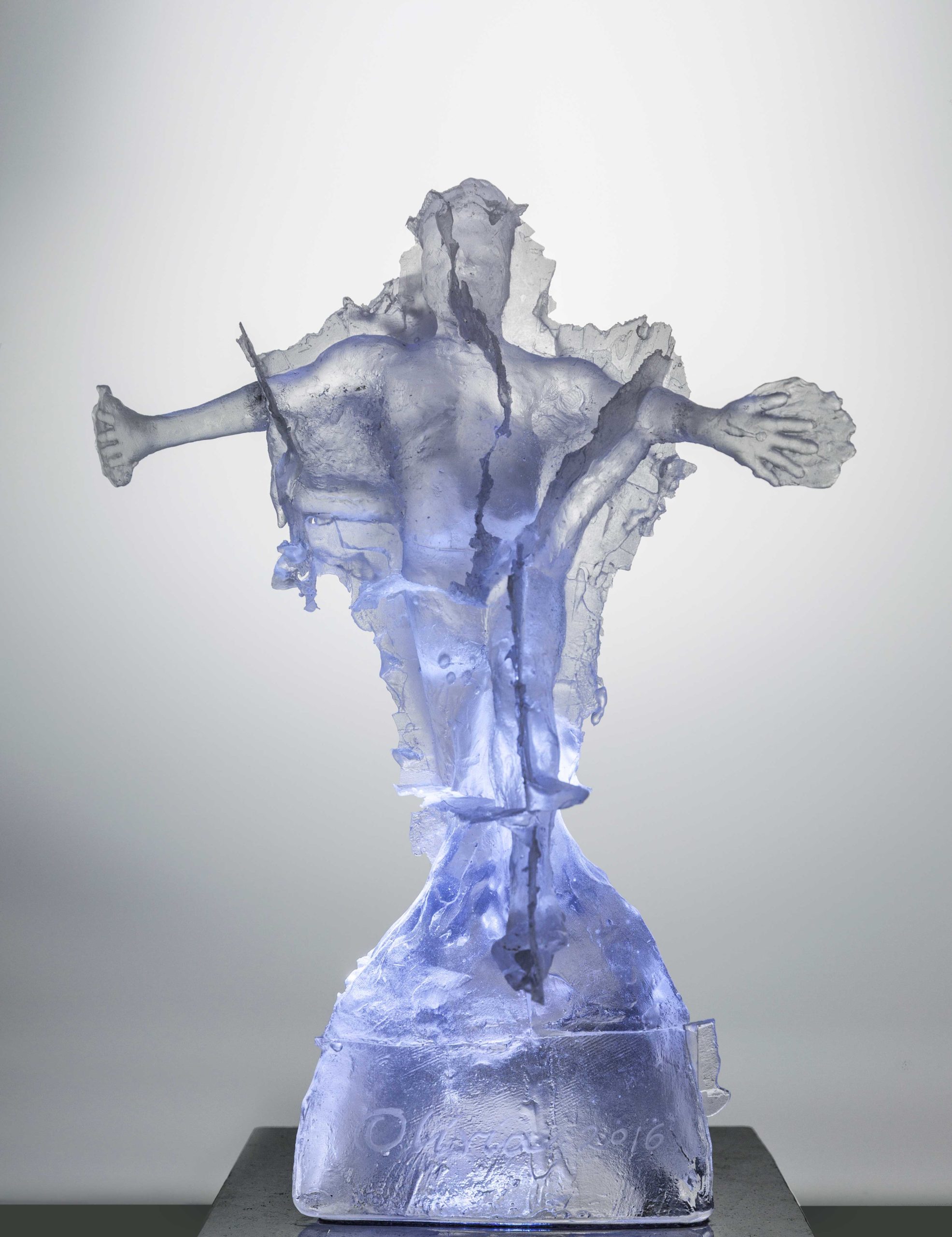

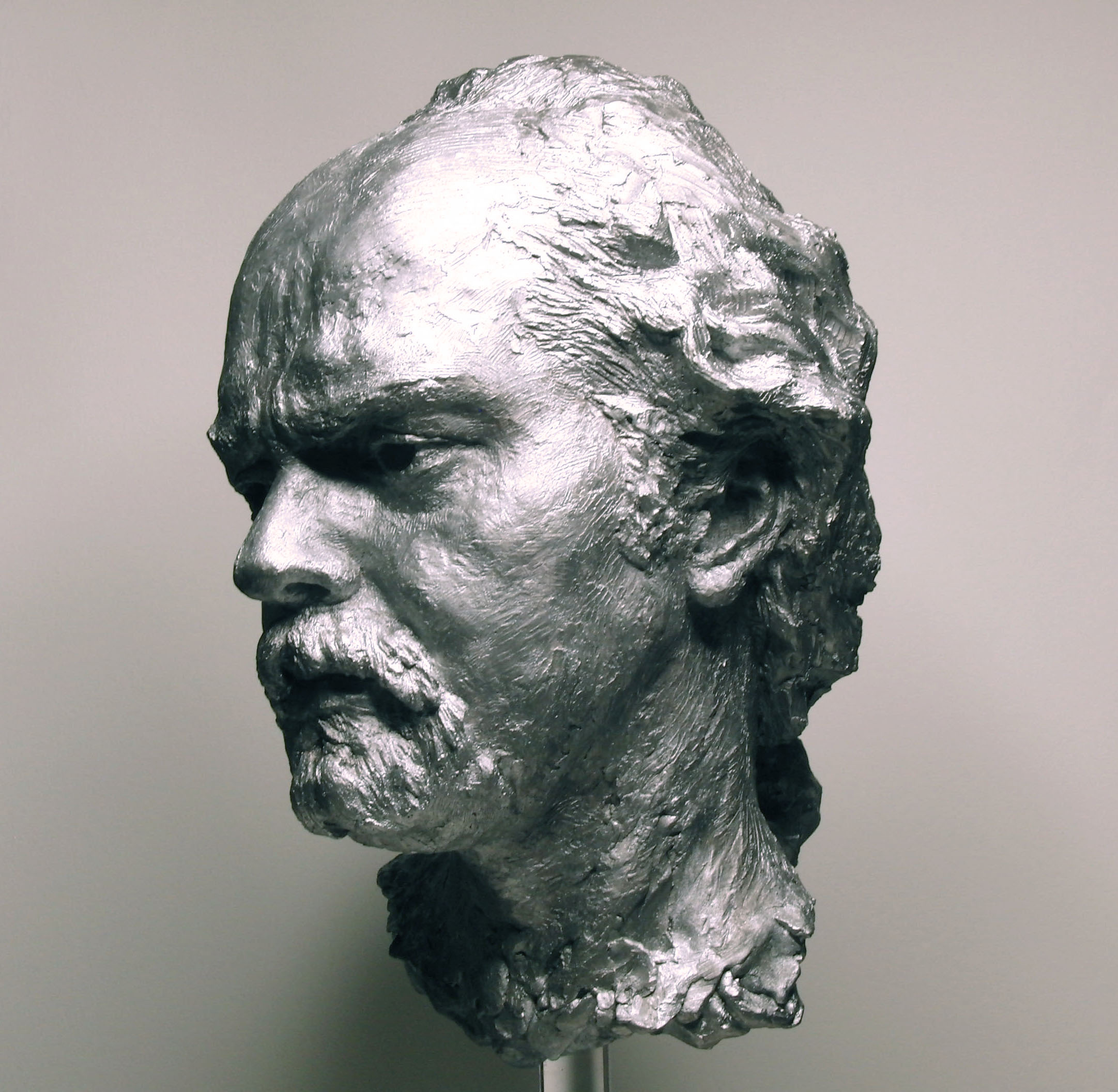

I work with various sculptural mediums because they express different aspects of human existence. Cast bronze is dense and heavy, yet conveys lightness depending on the refraction of light on the forms. Glass has the capacity to express emotional or more ephemeral observations of human existence due to its possibilities of transparency and sensitivity to light. When clay is damp, its makeup is akin to the water in our bodies, and the modeling of clay can be as mutable as water. Once it is in the ceramic state, clay becomes an earthier solidity, with only traces of its former fluidity. It feels more like our bones.

As I observe more links between emotional, mental and motion dynamics, the range and expression of my artwork grows. I believe capturing actual physical dynamics in art adds a wholesome element to images of the body. It reminds us to cooperate with our bodies, because our existence is not a mere image. We are an organic actuality that is constantly shifting to rediscover balance from moment to moment.

ABOUT OLIVIA KIM

Olivia is a figure sculptor based in Rochester, New York. She graduated cum laude with Divisional Honors in Ceramic Sculpture from the School of Art and Design, NYSCC at Alfred University of Alfred, New York in 2001. In 2004 she completed four years of graduate studies in Realist Drawing and Sculpture of the Human Figure at the Florence Academy of Art in Florence, Italy. There she received Prize for Best Sculpture. Olivia’s artwork is displayed publicly and privately in Europe, Australia and America.

Website: www.oliviakimstudio.com

Visit EricRhoads.com (Publisher of Realism Today) to learn about opportunities for artists and art collectors, including: Art Retreats – International Art Trips – Art Conventions – Art Workshops (in person and online) – And More!