How a still life commission led to a gratifying collaboration between artist and collector

Still Life Art: Northwest Meets Southwest

BY ERIC WERT

I used to be hesitant to take on private commissions. As a realist still life painter, each painting takes a lot of time, and it is important that each fits within my overall body of work. The prospect of making a commission piece that may be too much of a departure from current concerns in the studio felt risky.

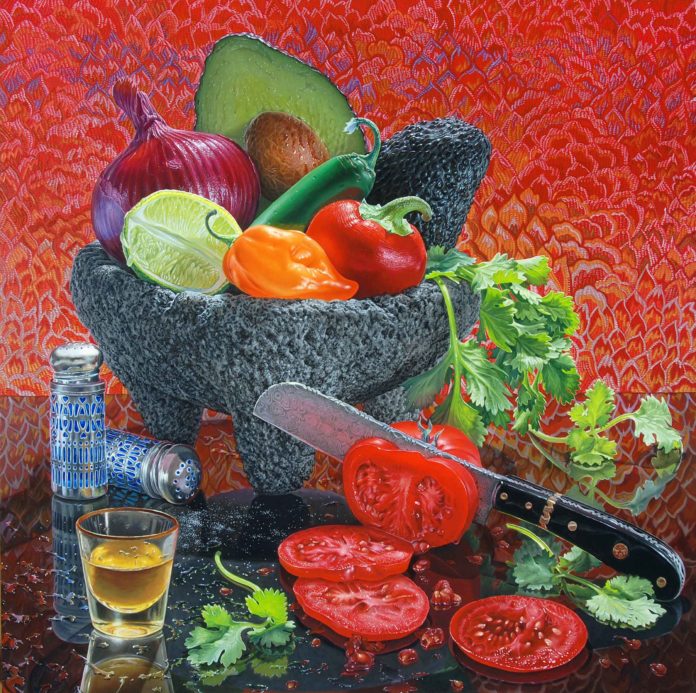

I no longer feel this way, after having had a rewarding and enjoyable collaboration with a collector to paint “Mola Salsa” in 2013. The collaboration allowed me to explore subject matter and ideas that I would not have on my own, and it provided the collector with a more personally relevant painting.

The collector, who is from the Southwest, suggested a still life that included the elements for making traditional guacamole. Initially, I was wary of this idea – I am from the Pacific Northwest and have little connection with such Southwestern subject matter. Subjects of my paintings are usually chosen for their formal qualities, rather than to illustrate a narrative or recipe.

Much of my recent work, however, has been focused around intense color and swirling, all-over compositions. As a lover of spicy food, I thought about the fieriness of Southwestern cuisine, and how that might be conveyed visually. To find some common ground in the creative process, I asked the collector if he had ever eaten anything so spicy that he became delirious; perhaps that was what the painting could be about. He responded enthusiastically, and I knew we were on the same page for the project.

Most of our collaboration was online, which at the time was a new and interesting process for me. We live several thousand miles apart, but used eBay to look together for interesting props. He suggested objects based on their relationship to the narrative of the piece. For example, I’m fixated on shiny metal and glass; it would never have occurred to me to include the lava bowl used for grinding the guacamole. After several false starts, I started to understand how the subjects could mirror or contrast each other in interesting ways—the swirling design in the Damascus knife, played against the juicy pulp of the tomato, or the pebbled dark skin of the avocado reflected by the rough lava bowl.

As we began to agree on props, I would set up arrangements, take photographs and get his opinions on compositions. We had a back-and-forth discussion about the elements that would be included. He suggested that a lace doily be made part of the still life. I felt that the doily might not fit the tone that I imagined, but his suggestion made me think of including cilantro leaves, which are airy, and filigree added a delicate element that integrated well into the overall theme. The collector also suggested including a shot of tequila in the foreground. I would not have included that on my own, but it made sense as an entryway into the scene- like Alice’s drink in Alice in Wonderland – drink the tequila and you see the rest of the painting swirl around you. These elements were brought into the painting collaboratively, and added more variety to the picture than would have occurred to me independently.

I work from three different sources in varying proportions: photographs, life, and imagination. Each of these takes different precedents at various stages. The ultimate goal is to make the best painting, without obligation to a photograph or to reality. An example of this is the background fabric in the piece. In reality, the fabric has an intense flame pattern but its original color scheme was very different, and too subdued. I wanted to incorporate the design but needed a more fiery color palette, so i used red, and then incorporated the accent colors from within the subjects of the painting. Even though my paintings appear realistic, I find I use imagination and invention as much as observational or technical skills.

My paintings take a long time. I work with perishable objects, so I need to take hundreds of reference photographs of each subject when composing a painting. Each element is photographed individually and from many points of view so that I have a thorough understanding of the object and its three-dimensional form. With this approach I am not limited to a single photograph of the item if something needs to be turned, changed or added, and I can manipulate the elements to create the optimal composition. In a way the finished painting becomes almost a collage of sources, rather than a record of a scene that really existed.

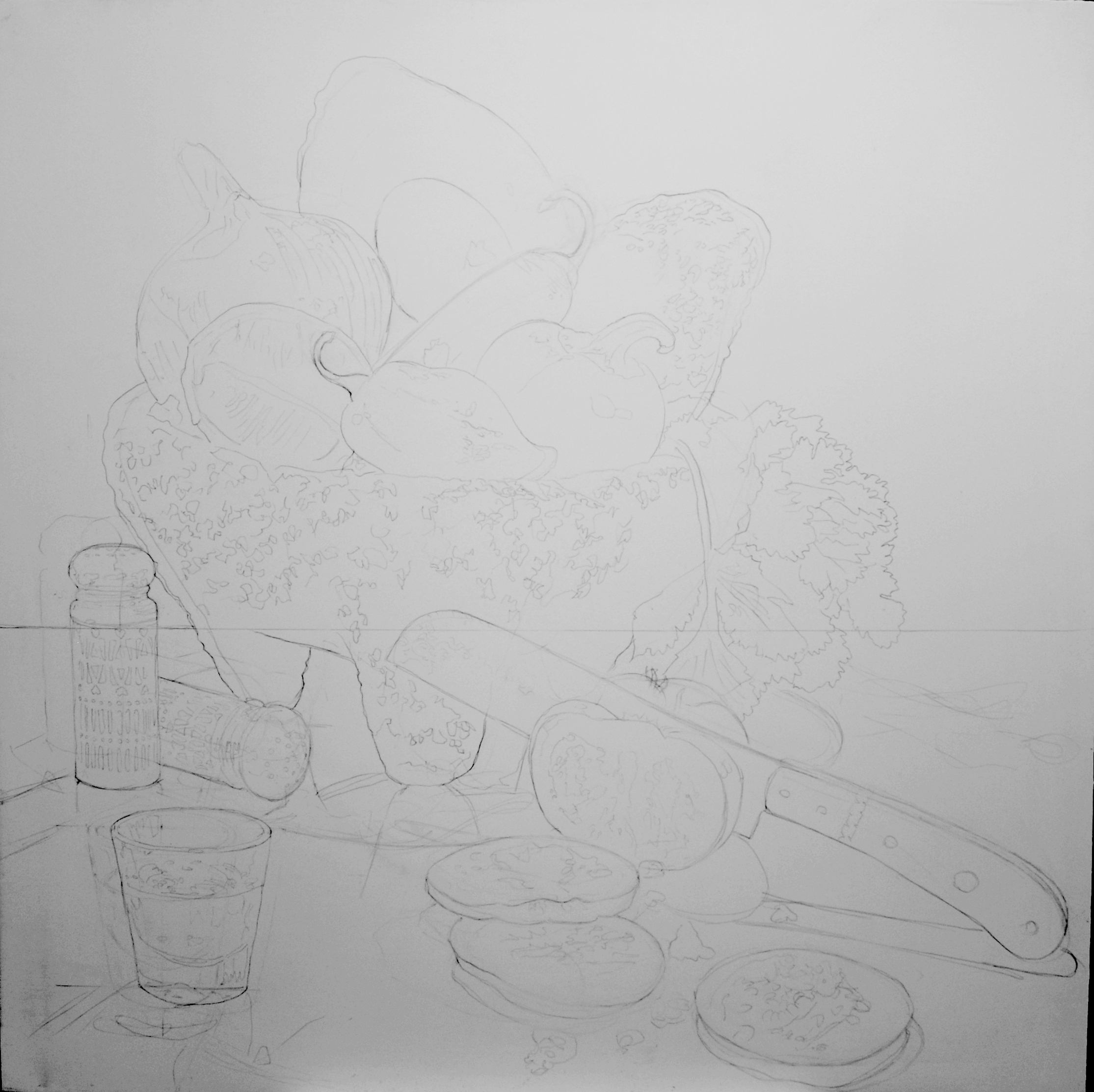

My first step is a very light line drawing. At this stage, I can focus on composition, the right balance of forms, proportions, and movement, and it is easy to make lots of changes. The photograph below may not clearly show it, but every element has been erased and redrawn a couple times to find a good view of each object and a fluid interaction between elements. The line drawing stage ensures that all the elements are portrayed accurately, and interactions between objects that may be confusing or that flatten the space can be avoided.

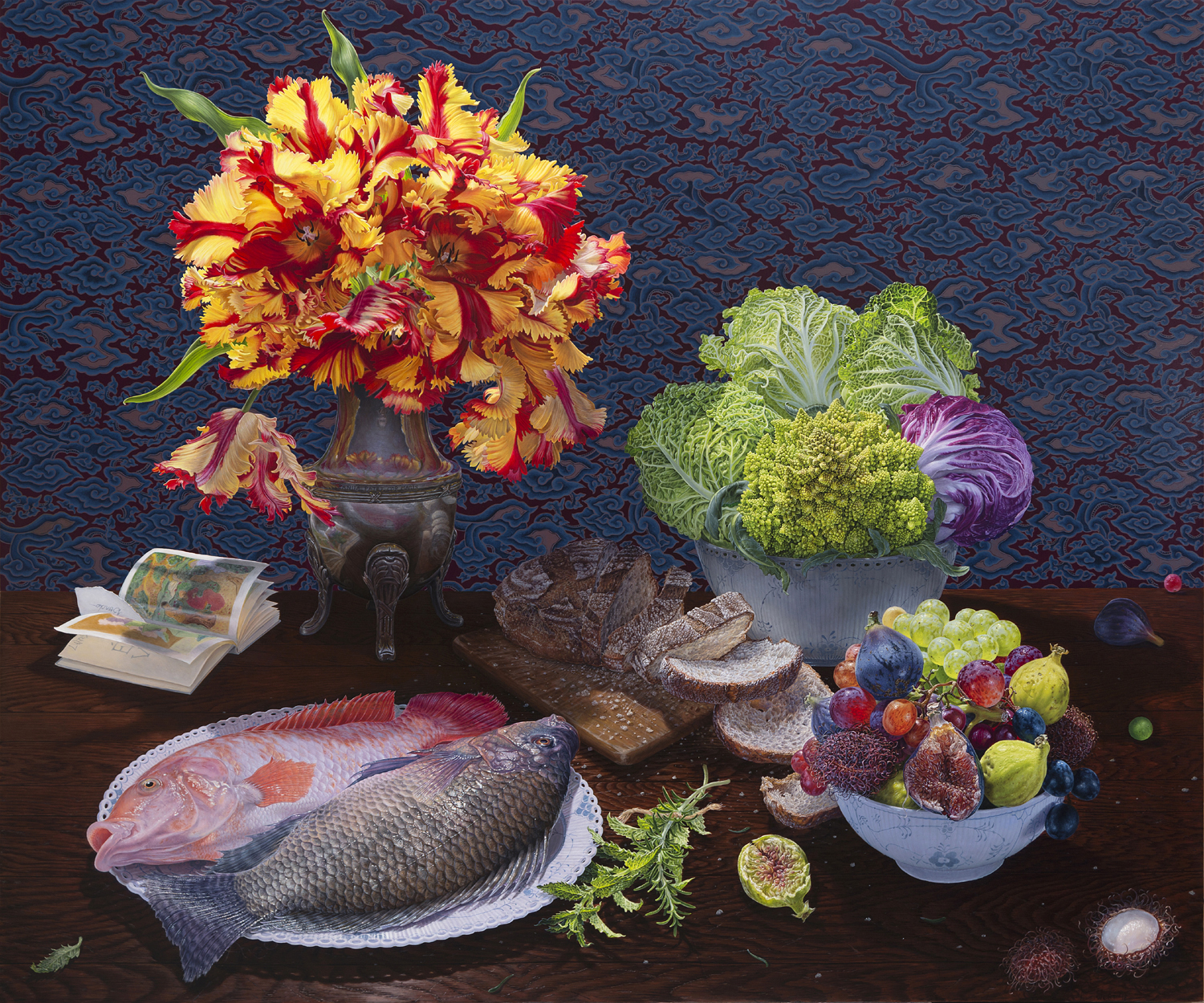

The next image is grisaille, a black and white under painting technique that has its roots in Renaissance painting. At this stage the local values of each object are established, and I can get a sense of the basic relationship of light and dark values. I used to work more directly, without such an explicit under painting, but as the work became more complex, I needed a way to organize the structure more fully.

I looked to the intricate work of the Dutch Golden Age painters like Jan de Heem and Rachel Ruysch, and realized that I had to learn to make the work in a much more traditional fashion. Working with a grisaille makes the painting more labor intensive, but also makes the later stages much less stressful, and makes it possible to achieve more clarity and luminous color. The grisaille is left a bit lighter in value because it will darken as color is applied.

Next is a high-chroma under painting. After the grisaille is dry, I apply a thin layer of the most intense transparent pigment of the local color for each object. It is always possible to make a hue duller but it is not always possible to return to the intensity that is achieved when layering a transparent hue over a white ground.

The last step is to settle in and resolve the painting. The preparatory steps were concerned with basic color value and composition, and thinking about the painting as more of an abstraction than as a representational image. It is important to ensure that the major formal qualities are engaging and balanced before starting to paint any details. Once those elements are developed, I can start concentrating on resolving all the surface textures and details. With the preparatory material done, the rest can be painted in a rather direct fashion with each element painted wet into wet. Reference to both photographic sources and to real objects are used to paint the still life elements.

If possible, I like to have the object I’m painting in front of me to understand its tactile nature, which can often be misleading in a photograph. For example, the pockmarked stone bowl appeared much smoother in photographs, but I could exaggerate that structure based on observations of the real bowl. For most subjects, I like to hold them in my hand while working, and be able to move my fingers over the surface to get a sense of their tactile qualities. I was fortunate to see an exhibit of paintings by Willem van Aelst years ago at the National Gallery in Washington D.C., and was struck by how tactile every element in his painting appeared. That quality has become something I strive for in my work.

Reflections on the tabletop and water droplets are usually invented; no real surface is quite as uniformly reflective in the same way. Over the years I’ve developed some techniques for inventing reflections and I like the way they both reflect and distort the reality of the still life to add an element of abstraction or fantasy, and convey an almost dreamlike quality. Having painted these elements many times, I now feel comfortable inventing them in ways that draw the eye around the painting to complement the composition or add movement.

Despite my initial concerns, this commissioned painting was creatively satisfying. It forced me to work with subjects I would not normally consider and created a work of more personal significance for both artist and collector. I have come to see creating a painting as a collaborative experience, and this project opened my eyes in ways that have led to many of my favorite paintings over the last few years.

Eric Wert is represented by Gallery Henoch in New York, and by William Baczek Fine Arts in Massachusetts. Learn more at www.werteric.com or on Instagram @ericwert333.

Browse more articles about still life art at RealismToday.com.