On figurative art: “Drawn from lived experiences, the work I make records moments as a diary but also points as a metaphor for larger issues,” says Charis J. Carmichael Braun.

BY CHARIS J. CARMICHAEL BRAUN

I feel like I begin in the middle: somewhere between the birth of the idea and the painting fully realized in my imagination. Distilling this into paragraphs, I’m excited to explain my process because it has lately been clarifying itself in the gray matter of my brain.

Perhaps my response to the thick gray areas of life is what makes me use kaleidoscopic color in my artwork (Another probably theory: I’m a squeezer, not a mixer). You see, I grew up in a worldview that emphasized a black/white mindset in regards to authority (e.g., good ≠ bad, heaven vs. hell), while also holding a reverent duality towards spiritual matters (i.e., “sinner + saint,” “life + death”). Springing from the theme of two opposite things existing simultaneously, I sift desire, fear, and faith to combine concepts I think are mutually exclusive. Attraction and repulsion, masculine and feminine, ideal and flawed, repressed and exalted, I blend contrasts in a painted image to create a middle ground where it is difficult to see where one begins and another ends.

My work usually presents a solitary figure in a natural or interior setting, obsessively developing the human form while allowing the environment to disintegrate. I find my subject matter in the familiar—my husband, my family, myself. Drawn from lived experiences, the work I make records moments as a diary but also points as a metaphor for larger issues.

To set my compositions, I use the photographic rule of thirds and/or the golden mean to position the figure in relationship to its surroundings. Asymmetrically balanced to connote tension, I pay close attention to how the lines of my brushwork and the gesture of the body imply vectors, inviting the viewer’s gaze to bounce around the canvas. I also pose the figure with angles and bends because I do not use strong chiaroscuro. I often find myself wanting to intensify the reflected lights or saturate the shadows—so much so that the descriptive brushwork blends into a close range of values as the pigments shift temperatures over the turning of the form.

CONNECTIONS

GUSTAV KLIMT & THE GROUP OF SEVEN

In the early years of my relationship with my husband, we commandeered my folks’ mini-van and road-tripped from Minnesota to Canada to see a rare Gustav Klimt retrospective at the National Gallery in Ottawa. Along the way of our youthful misadventure, I’d plotted to see sites the Group of Seven had painted, fantasizing about any genetic link that might be improbably pulled from Franklin Carmichael.

VENI, VIDI, COLORATI

I came, I saw, “I colored,” or something like that. My Latin might have faded a little.

My first art professor was enamored with the Impressionists, the Beatles, and the Green Bay Packers. Bill Bukowski taught all sections of painting in college. In the first lessons—still lifes, of course—he noted that optical blending could be electrified by underpainting the opposite of the intended color of the object. To this day, I lay the foundation of my canvas with hues I want to spark through to the final surface.

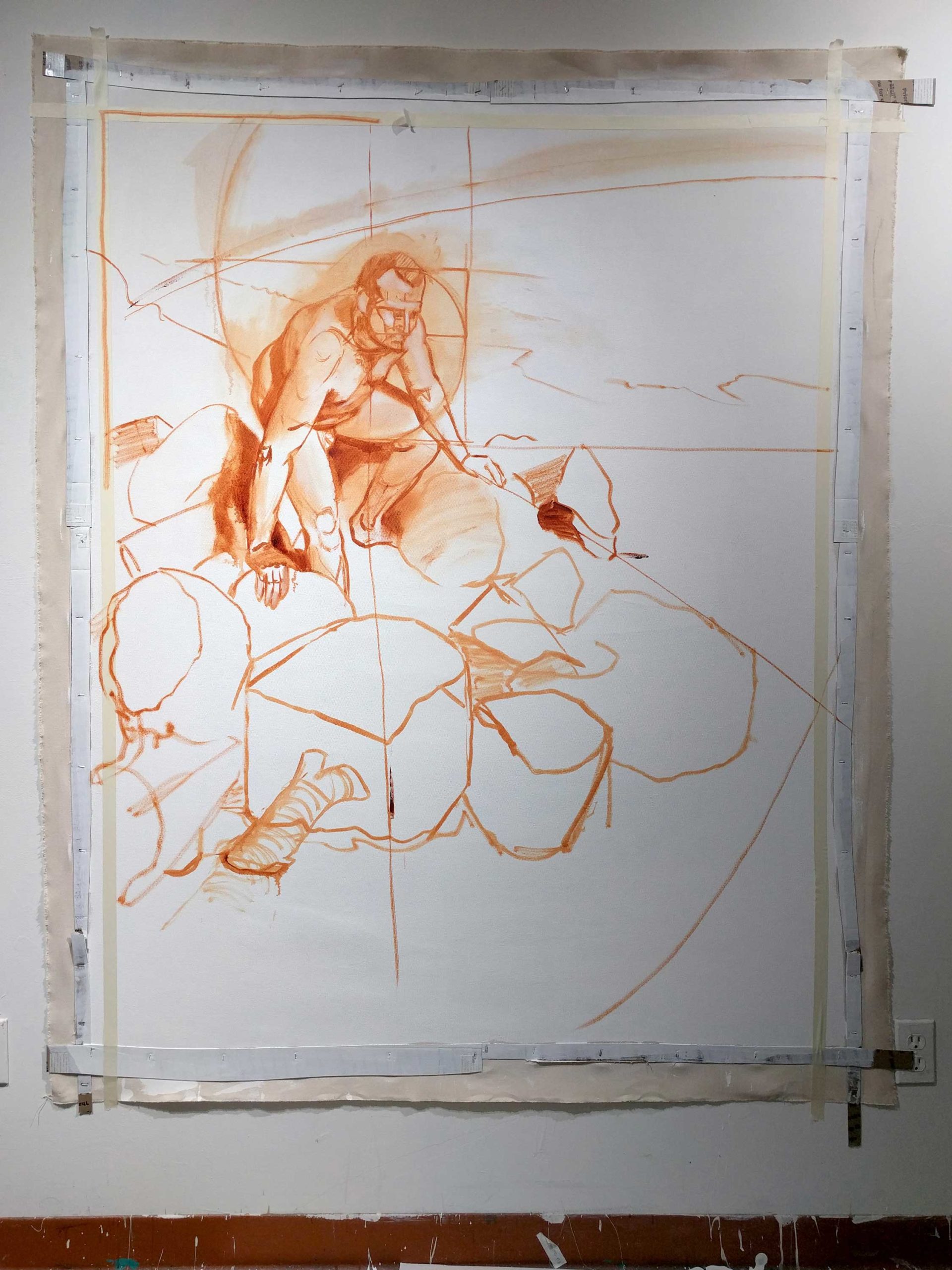

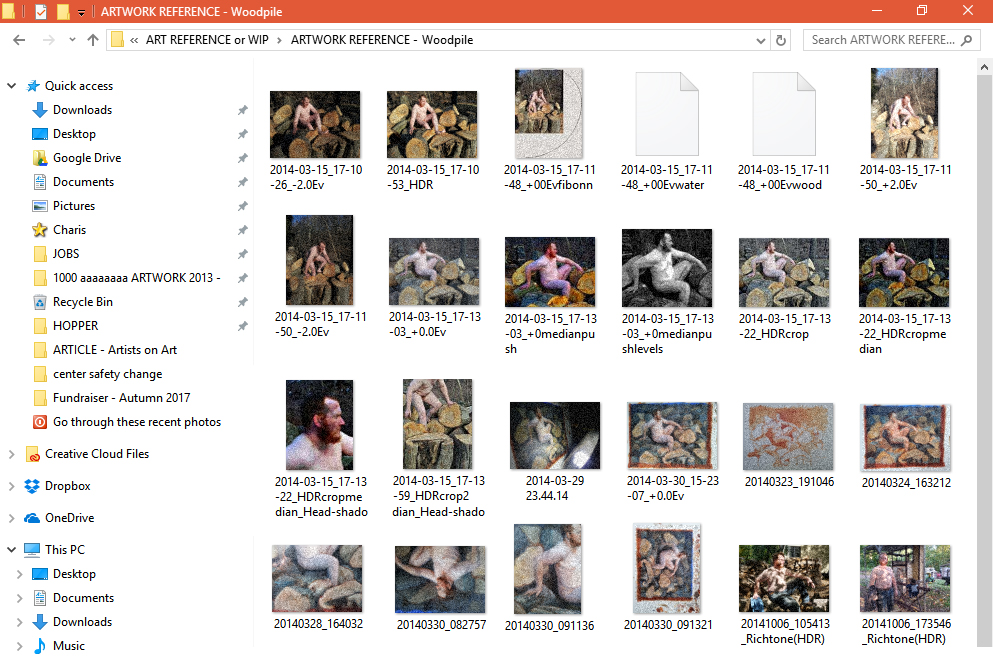

Below: These three studies show the different effects that light can have on the perception of “skin.”

A BOWL OF FRUIT SALAD

I have had the privilege of being a participant at human dissections a local medical school made available to art students. I was astounded at how much color lives underneath the skin. Fat deposits appeared like butternut squash, the kidney was a bean-shaped red velvet cake; the brain was a cauliflower. The “bowl” of the pelvis carries an anatomical cornucopia: in the cadaver’s thorax, I was seeing the hues of blueberries, honeydew dried in the sun, sliced peaches. (Interestingly, even though the actual dissection theatre caused me to wretch, afterwards I felt an irrepressible urge to eat a sandwich.) Now knowing what lies beneath, when I look at any person, any time, in my mind I start loading my palette with juicy paints.

Related Article > Figure Drawing Basics: Dan Thompson on Drawing Cadavers

CATHARSIS

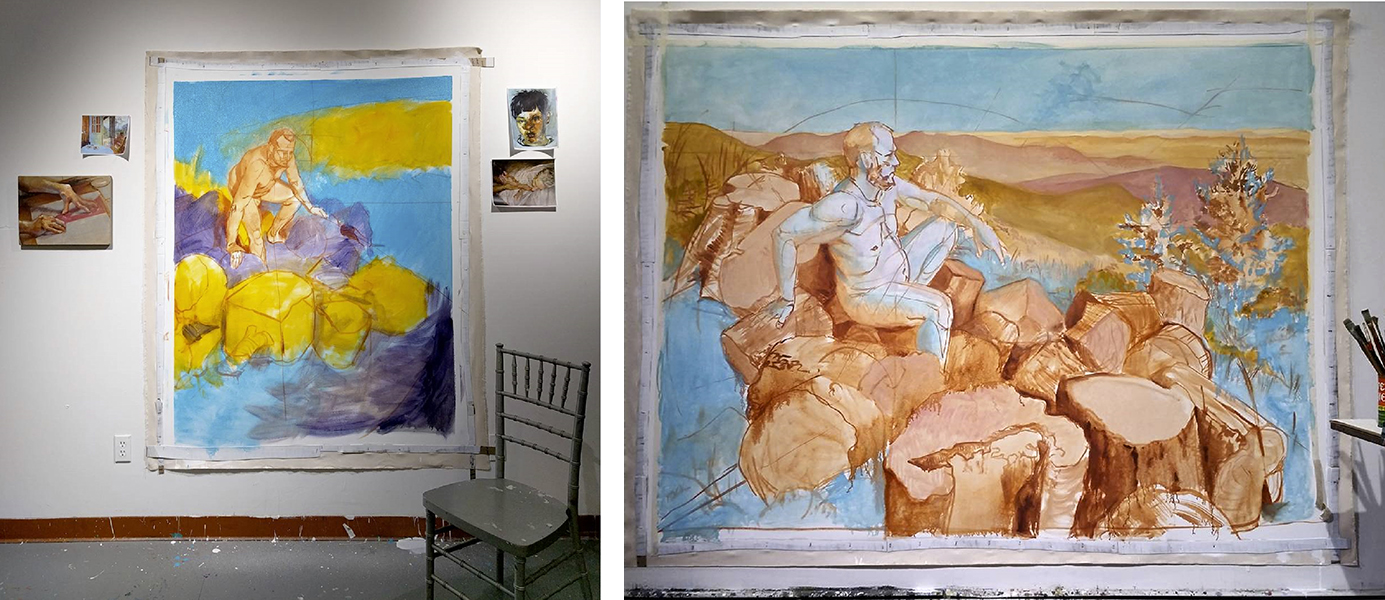

While I was trained in “academic” schools of thought using tried-and-true techniques, maybe (as an un-admitting Millennial influenced by MTV) my attention span has grown shorter. As such, I don’t adhere to one time-honored process. I do know how to employ a proper imprimatura or grisaille, and am mindful of fat over lean. My own process has, however, evolved into a mix-and-match of Bargue and Gesture drawing, impastos and velaturas, peeking-out underpaintings and layers upon layers. Since grad school, I’ve been getting closer to drawing out my own voice. The process that weaves together to the final image, in “exploded view,” looks like this:

Once my canvas is grounded in plain white gesso, using a rough grid I sketch a quick imprimatura in traditional transparent red oxide to mark out territories.

Blank canvases petrify me, so I’ll wash a couple of vibrant hues onto the sketch to separate elements. This helps me to create mood and movement—and reduces my unease by giving me something to which I can respond.

I apply oil paint again and again on the canvas with anxious compulsion, almost as if I were working in Photoshop layers. I am sensitive to the frisson of chromatic vibrations, so I ensure that the image is compelling both when seen from a distance as well as when the viewer zooms in to see each “pigment pixel” on the surface.

CONCLUSION

Moving slowly now, surgically—I bind up the wounds with strategically placed brush-strokes. As all the parts knit together, the painting seems to begin to “breathe” on its own. My work keeps company with me in the studio for a long time. As I develop other pieces, I see parts of “resolved” works that need a little brushstroke band-aid here and there. A painting is only finished when it walks out of my studio in the arms of someone who loves it as much as I do.

ABOUT CHARIS J. CARMICHAEL BRAUN

Charis J. Carmichael Braun grew up in New Ulm, MN. She earned her MFA from the New York Academy of Art. She has received a Juror’s Award for her work in Representational Art in the 21st Century exhibition at the University of Hawaii at Hilo, HI and was chosen as a Sing For Hope Piano Artist. In 2020, she received a grant from the Huntington Arts Council (Long Island, NY) for her Beekeeper Portrait Project. She has been published in PoetsArtists, The Huffington Post, LINEA: The Artist’s Voice and Artists on Art. Charis currently lives and works in New York.

Website: http://www.charisjcarmichaelbraun.com

***

This article is sponsored by the PaintTubeTV Art Video Workshop, “Chantel Barber: Painting from Photos“

.