Terry Miura shares his process for painting figurative art that is evocative and mysterious: “The process I follow in creating my figurative works varies from piece to piece, but they start similarly…”

Painting Figurative Art: Secrets and Private Thoughts

BY TERRY MIURA

If there is one thing that I consciously try to imbue in all my figurative works, it is a sense of mystery. I love mysteries. Like secrets and private thoughts, what is unsaid is intriguing and irresistible. There is a narrative to go along with the shadowy, contemplative figure, but we don’t know what it is. It tempts us to imagine.

The notion of mystery in a painting came to me gradually. As a student, I really enjoyed painting likenesses and details—the more information, the better. As I became more proficient, I noticed I was always drawn to quiet, moody pictures. I also noticed that these pictures didn’t have a lot of detail in them, but I didn’t miss it. Not only was it OK to exclude details, but I actually preferred not having everything spelled out. Why was that? I think it was because the lack of information allowed me to complete the picture in my mind, in the context of my own experiences and memories. I could relate to the picture, because my mind made it personal to me. If everything was spelled out for me, there would be no way for me to make the experience my own. I would be a bystander, not a participant.

Mystery = Withholding Information

But how does one create mysteries in a figurative painting? As with any good story, the narrative provides us with clues–just enough information to pique our interest but not give us the whole story. It’s about what we don’t know that’s important. What’s left unsaid. My job, then, is to withhold information. If I had a choice between revealing a person’s identity and hiding it, I must hide it. If I chose otherwise, I can’t ask the question, “Who is she?” If she is looking at something, I may leave unpainted the object of her contemplation, so that I may ask, “What is she looking at?”

The process I follow in creating my figurative works varies from piece to piece, but they start similarly; it is a method I came up with in order to limit my capacity to be tempted to include unnecessary information.

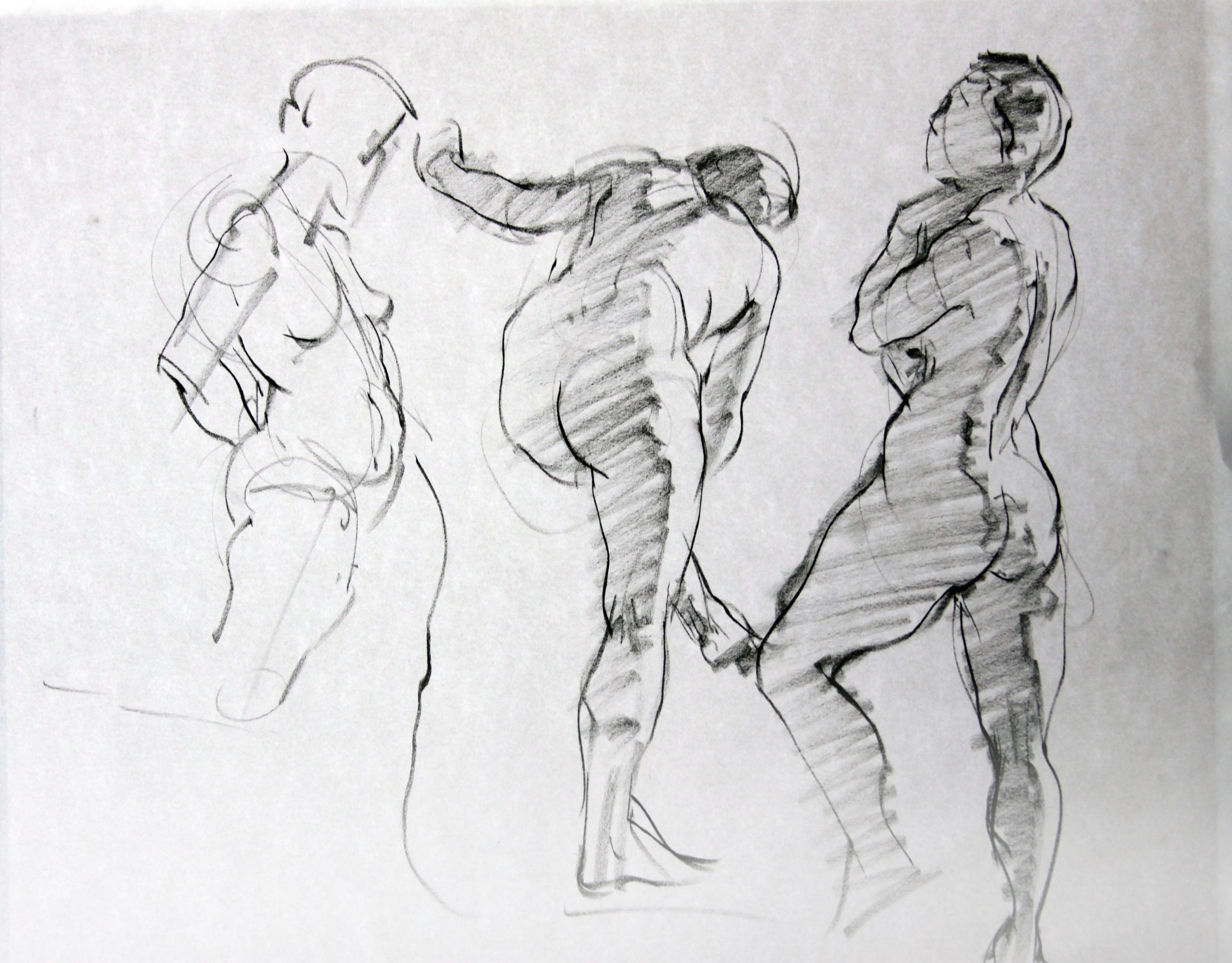

I start by going through hundreds of short-pose gesture drawings. Because these are done very quickly—most of these are five- or ten-minute poses—I can only include so much information. In these drawings I focus on the gesture, and while I have light and shadow patterns indicated, the shadow areas are just simple fill-ins. There is no value modulation aside from the shadow side being darker than the light side. I have no indication of highlights or half-tones, either.

There’s no time to draw facial features, so I’m forced to leave them out. I tend to work from the center of the torso outward, so often I don’t get to the extremities within the given time frame, which forces me to suggest hands and feet only gesturally, and not define every finger and toe.

Related Article by Terry Miura > Figure Drawing and Economy of Line

Once I pick out a drawing, this is the only reference I use to make the painting. There are no additional photo references, and I don’t work with a model at this stage. As noted above, my reference offers very limited information, so you see, I can’t paint details even if I wanted to.

I choose a drawing based on pose. I don’t like poses that look like they can only happen on a model stand in a classroom situation. I prefer natural poses which could have been a snapshot in a privacy of the boudoir. I look for a quiet, evocative quality, paired with shapes that reveal a recognizable contour. This point is important because as I remove much of the anatomical information, I’m often left with a silhouette. If this silhouette doesn’t describe what the figure is doing, I really don’t have anything left.

I draw the figure on canvas with a brush, and proceed to recreate the drawing using a neutral transparent mix of Ultramarine, Transparent Red Oxide, and Gamsol. If I’m doing a black and white painting, I just use Ivory Black and Gamsol.

From there, I work to build a more-or-less straightforward representational figure painting, with as much information as my reference allows. In fact, I go much further and make up missing information by analyzing the light source, and modeling form accordingly, to the best of my ability. I’m not an anatomist so I don’t usually get too much into small parts, but I try to paint a convincing figure as if I had a model in front of me.

Obviously, I don’t have color information in my reference drawing, so I have to make it up. This isn’t as complicated as it sounds, really. The colors only need to work in the context of my painting, so as long as the value structure is sound and the harmony is working, matching the exact skin tone is a non-issue.

Edges and Figurative Art

Once I have a decent representational figure painting, I start to look for ways to deconstruct. I typically start by looking for ways to connect shapes by losing edges. Two adjacent shapes of similar values, especially dark shapes, are the easiest to connect, but I try it with light values as well. Sometimes losing edges means losing vital information, and I have to reestablish that edge. If I lose an edge between two shapes, I now have one shape, and whether that shape works or not depends on all the other shapes in the painting, so I find myself losing and finding the same edge repeatedly. Sometimes it’s a long, uncertain process.

Every time I eliminate an edge, I take out information. Every time I take out information, I create more mystery. In this way, I keep pushing toward more mystery until I’ve gone too far and I don’t have enough clues left for the painting to be compelling. I want the question to be “Who is she?” not, “What the heck is that?”

Not painting facial features in figurative art is another way of creating mystery. I may immerse the face in shadow, or have the head turned away from the viewer. I may crop half the head, or take a palette knife or a scraper and go right over the face, integrating it with the background and abstracting at the same time.

An abstract treatment of an area means a move away from the representational, so that’s another way of looking at withholding information. It turns out I can get quite abstract with parts of the figure, especially if the background has a lot of the similar treatment. By establishing a non-representational context surrounding the figure, the abstraction of the figure itself is much more likely to look appropriate. The act of pushing paint around with such uncertainty is in itself a mysterious process, and I find it fascinating and seductive.

The results are unpredictable but I think that’s precisely the point; not knowing is exciting.

Who is she? What is she doing? What is she thinking? Why? I ask these questions when I’m painting the figure, but I don’t provide answers. I want the viewer to look at one of my paintings and ask the same questions and come away with his or her own narrative. To complete a picture in the mind of the beholder is a far richer experience than just looking at a pretty picture.

ABOUT THE ARTIST

Terry Miura graduated from Art Center College of Design in 1990. He paid his dues in New York City, working as a freelance illustrator for such clients as Time, Newsweek, Rolling Stone and Sports Illustrated. He returned to California in 1996, and began a 10-year transition into becoming a full-time painter.

His evocative and atmospheric landscapes, cityscapes and figurative art works are widely collected, including pieces in permanent collections in the California Museum of Fine Art, the Crocker Art Museum, and the Smithsonian Institute.

Connect with Terry Miura:

Website | Instagram

Register for Realism Live, a global virtual figurative art conference and more, October 2020:

Thank you for all the information. I want to lean towards that direction but didn’t really know how to start. This has helped a great deal.

Comments are closed.