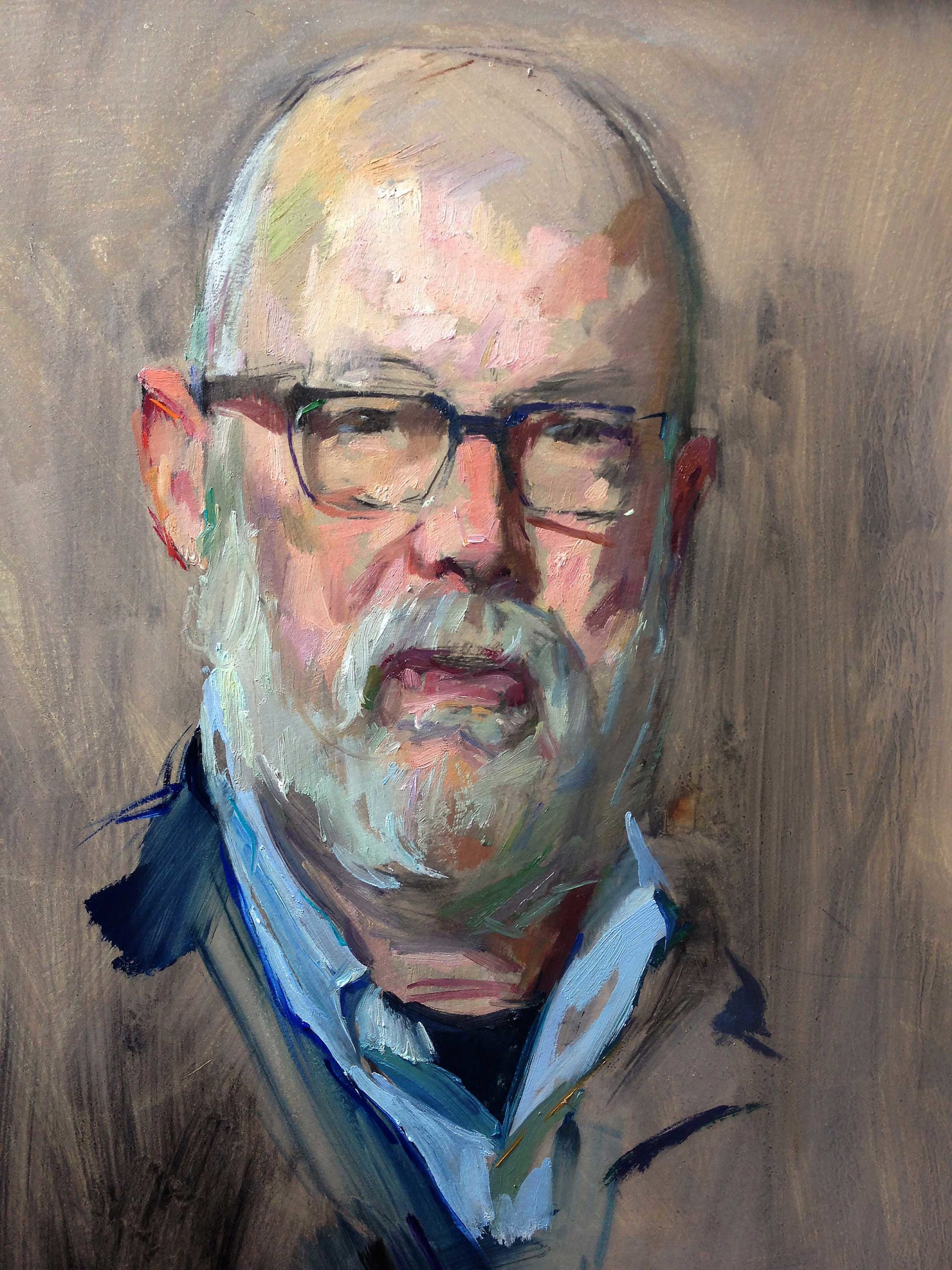

An essay by Ghanaian-born painter Samuel Adoquei on historical artists and timeless beauty, the difference between skin tones and flesh tones, and ways to capture beautiful skin tones in figurative art. The following is an excerpt from his book, “A Short Story of Skin Tones in Art.”

Figurative Art: In Search of Timeless Beauty

BY SAMUEL ADOQUEI

samadoquei.com

When you study portraiture over the ages—especially when you compare portraits of different schools, eras and traditions, such as the German Renaissance artists Lucas Cranach and Albrecht Dürer, Italian High Renaissance artists Raphael (Raffaello Sanzio da Urbino) and Titian, the French portraitists Jacque Louis David and Dominique Ingres, the Spanish artists Velázquez and Goya, and the Impressionists Manet and Degas—you will notice how their portraits fall into certain categories: natural, idealized, stylized, caricature, cartoonish/exaggerated and commercial.

There are painters like van Gogh and Albrecht Dürer, who, because of their compassionate and sympathetic nature, look for, attract and distill compassion from their sitters. Then there are commercial portrait painters who paint to get the job done, aiming for an accurate resemblance of the heads and faces they encounter.

These artists scan over faces, copy features, glaze over experiences disguised as scars, and miss the soul and humanity of a unique being worthy of the artist’s highest effort. There are also portrait painters who have some idealized beliefs of what portraits must look like, and these painters come in and project or impose those characteristics onto their sitters.

Naturalistic painters like Rembrandt, El Greco, and Velázquez try to preserve the beauty of their sitters—without imposing certain ideas onto them—as a means of praising our Creator’s creation. These artists see humans as divine souls, unique individuals, great achievers, and beautiful friends, neighbors, and relatives. Some of the greatest portrait painters, such as Raphael, are blessed with special spiritual sentiments and humanistic temperaments.

With their spiritual beliefs and thankfulness for God’s creation, they paint to honor the souls they meet. To these painters, individuals are more than just wandering people. They are special souls whose mortal, human nature must be recorded and preserved for posterity. Studying these artists and their insights plays a role in determining the sensibilities we develop and how we approach skin tones.

When it comes to identifying which method best explains and teaches the techniques that capture the true colors of skin tones, the works of the Impressionists Monet, Cézanne, and van Gogh are more revealing than any others. The method of the Impressionists is the most practical and easy to understand.

It forces you to put colors close to each order—or to “juxtapose” them—in order to compare, relate, and judge the colors, allowing you to get your colors as accurate as possible. It’s based on the idea that in life colors look the way they do because of what’s next to them. Colors look or seem the way they look only because of where they are or what they are related to or next to.

The Difference Between Skin Tones and Flesh Tones

Skin tones, often called skin color or complexion, refers to the actual color of a sitter’s skin (black, brown, red, yellow, white, etc.) and is often called local color. Flesh tones, on the other hand, refer to the different nuances within the actual color. Within the black, brown, red, yellow or white skin color, there are several subtle combinations, or nuances, that are known as flesh tones. Like the yin and yang philosophy, many colors come together to make one color, and in one color exists many different colors.

For example, from a distance we see White complexion, Black complexion, Brown complexion, or Red complexion. When we look closer, we start to notice the blues, pinks, yellows, purples, and all the subtle nuances ranging from muted to intense mixtures, warm and cool tones. It’s just like looking at a computer image. If you reduce or scale down a picture to a smaller size, the picture will get as fine and detailed as possible. But enlarge it and you will see big squares of pixels. This is what the Impressionists tried to achieve in their paintings when painting from life.

To be good at skin tones in figurative art, a portrait artist must be trained to develop three skills: to observe in order to see well; to mix the right, natural colors; and to use color effectively. These are the methods and skills used by the Impressionists like Sorolla, Monet and Cézanne.

Of the many ways to achieve true, natural colors, there are three approaches common among colorists. The intuitive approach, theory and idealizing, and the technical approach.

How to Capture Beautiful Skin Tones in Figurative Art

1. The intuitive or natural approach

Our personal likes and dislikes give us an innate desire to make certain color choices. We all tend to select or be attracted to certain combinations of colors whenever we gaze upon an image. With time, the way we look, observe, analyze, and mix the true colors we see in people also change. Our instincts, our education, and illusions of what we think we are seeing are honed by training and experience. When we are honest, we see what an actual nuance is and respect its true nature.

The intuitive approach is the ability to be free and natural by having your knowledge, experience, and conscious reasoning give into instincts. Due to the lack of this intuitive approach, some critics think representational artists have lost their originality by following too many rigid rules. The rules that are supposed to set the artist free have become rigid doctrines that imprison them from nature’s hidden treasures.

A curious student once asked me, why is it so important to be intuitive, yet whatever I put down is wrong according to your standards? This is where we often miss the point of education. Intuition guided and guarded by education, experience, knowledge, and wisdom is how uniqueness finds its natural voice. To get the best of your intuition is to learn all there is to learn, then work to forget everything you have learned so that you can work with freedom and open-mindedness. Or, to put it another way, it means learning all the rules, then being merciless in breaking them all.

2. Theory and idealizing

When artists say “traditional,” they mean “realist” ways of painting, but in a broader manner it means what works according to time-tested results and a certain particular way of working. Thus, you can work in the impressionistic tradition or the classical tradition. With this theory, you do not need to be overly concerned with which tradition you use as long as the painting works. To enjoy a creative life, it’s best to choose an approach that goes with your temperament.

The graveyards of mediocrity and disappointed artists are filled with many talents who followed popular styles and traditions. Freedom and happiness in creative pursuit come when an artist chooses a tradition and technique that goes with his or her nature.

3. The technical approach

Another approach is to simplify and determine the local color of the subject’s or the sitter’s skin tone before you begin looking for the subtle nuances. By local color, I mean the one dominant color in the skin tone. Then try to see how this local color changes in its nuances from light to dark and from warm tones to cool tones. The total sum of nuances make the one local color. This approach has its roots in the philosophical or Eastern religious belief that suggests that one is all and all is one—“one” meaning the local color and “all” meaning the nuances and the combinations of nuances that come together to make the local color.

When it comes to determining which technique and method of capturing the true, natural nuances of people’s skin tones works best, some unfinished works by Cézanne and Monet reveal all the techniques you need. Freud was also a master of the subtleties of colors. Any close-up, detailed reproduction of one of his portraits offers everything worth seeing and gives all that which makes great art.

Sargent captures beauty in his creative genre paintings, but not in the nuances in his commissioned portraits. Sorolla’s paintings of peasants, workers, and ordinary people are great examples to study. Because of restrictions on commissioned portraits, the genre paintings and noncommissioned works of many great painters tend to be more innovative, stronger, and more personal.

Connect with Samuel Adoquei at samadoquei.com.

Related Article on Figurative Art > Is There More to Art Than Painting Well?