The Florence Academy of Art was established in 1991 by the American-born artist Daniel Graves (b. 1949) in the limonaia (lemon conservatory) of the noble Corsini family. From the very start, it was a bootstraps opportunity intended to reshape the future of art instruction; the young academy buzzed with the excitement of knowledge being transmitted, and the air was full of paint’s heady perfume. Graves felt he had a responsibility to pass along the flaming torch of the atelier to the next generation.

He recalls: We were exchanging information that we learned and gleaned and read about. Technical stuff from frame gilders and from Zecchi’s [the historic Florentine art supplies store]; all these local people who had so much knowledge. It was phasing out, and we caught it right at the end. There was the studio of Signorina [Nerina] Simi, whose father, Filadelfo, had studied under [the French academician Jean-Léon] Gérôme. There were all these connections back to that tradition. It was so rich and alive. We were in awe of everything, trying to absorb as much as we could, and we realized that there were many others who wanted to do the same thing.

Under Graves’s careful cultivation, the lemon-house was outgrown, ultimately superseded by high-ceilinged studios in a sprawling, refurbished warehouse complex just outside Florence’s historic center. Where today nude models pose for young painters and sculptors, once Italian customs officials supervised storerooms full of seized goods. Later these buildings became a restoration workshop, where pieces of furniture waterlogged during Florence’s catastrophic flood of 1966 were repaired, sanded, and oiled.

Graves and his administrative wizard of a colleague, Susan Tintori, supervised the transformation of these warehouses into a modern atelier with skylights and airy spaces. They sought a place where, in Graves’s words, “everyone feels equal, where there is no special group — an inclusive and safe environment. You have to teach people, but you also must create an environment in which students feel free to learn.”

Graves is quick to praise Tintori, who in the early days was responsible for finding students to fill the studios, and has been his partner in making the academy a popular institution ever since. Today it attracts students from around the world, lured to Florence by the irresistible magnetic pull of artistic tradition and methods gleaned through centuries of practice. The academy now offers a three-year certificate in Italy; runs a second campus in Mölndal, Sweden; and offers a NASAD-accredited M.A. in Studio Art program in partnership with St. Peter’s University in Jersey City, New Jersey.

Breathing the linseed air of the busy Florentine studios is a sensual reminder of the tradition, and the atmosphere buzzes with the energy of purpose and ambition. Students come to learn the techniques of the Old Masters, keenly aware of their role in the transmission of knowledge from master to student and beyond.

At Florence, students are immersed in practices derived from 19th-century Paris’s Ecole des Beaux-Arts: they work from models, learning the importance of measure and value, of observation and patience. In London in the 1980s, Graves rediscovered a portfolio of academic drawings printed in Paris by the now-forgotten artist Charles Bargue as a course in drawing for Gérôme’s students and admirers. Graves realized that this was a trove of forgotten knowledge, and so arranged to have photographs made and brought them back to Florence, where he revived the practice of teaching from them. News spread, and the Bargue drawings are now a fundamental of contemporary atelier training worldwide.

A Chapter Begins at Florence Academy of Art

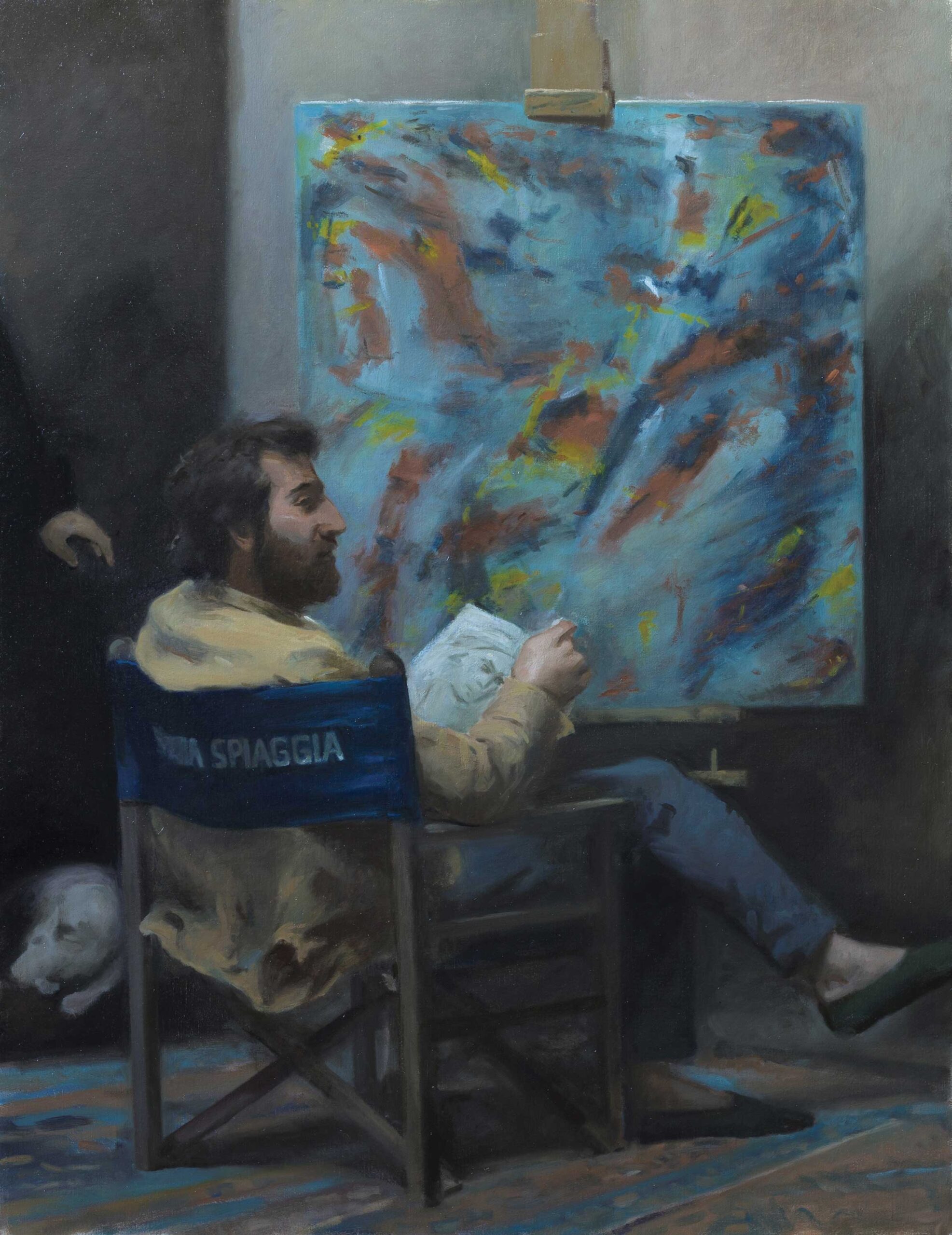

At the end of 2022, Graves retired from the academy’s directorship in order to head its etching program, and he could not be happier about the recent appointment of his successor, Tom Richards (b. 1982). Graves says Richards is “one of the most delightful people, knowledgeable, talented. I literally cannot say enough good things about this man. He’s the ideal person to take over. I’m so fortunate! The students love him, the teachers love him.”

Lineages matter in the world of ateliers, and Richards shares a pedigree comparable to that of Graves, whose pedagogical inheritance descends from Gérôme to Filadelfo and Nerina Simi. Richards studied painting under both Graves and the American-born, Florence-based painter Charles H. Cecil, who trained with a pupil of the Boston School master William McGregor Paxton. Paxton was in turn a student of Gérôme, who learned from Paul Delaroche, painter of the still popular Execution of Lady Jane Grey (National Gallery, London).

This transmission of knowledge across generations lends a depth to the academy; its instructors offer what is virtually a priestly laying-on-of-hands as they initiate students into a lineage connecting them back to the Old Masters. Going forward, then, the students’ work becomes not only a pleasure but also a responsibility. This reminds us that society is a contract between generations — between the dead, the living, and our descendants.

In 2022, I met Tom Richards in the academy’s lively cafe, across a courtyard from its spacious gallery. He sat at a scrubbed refectory table and reached for a frothy cappuccino — a tall Englishman dressed in a gray linen shirt and chinos, with lively eyes and a sprawl of dark hair. Behind him, the staff were busy preparing tasty treats and wiping steam off the shiny espresso machine. “They keep the students happy,” Richards confides, “because everyone here needs caffeine.”

Richards grew up in a London home adorned with oil paintings; living with art was normal, and expected. His mother took him to the capital’s great galleries — he especially remembers seeing masterpieces by Caravaggio and Monet — and those visits created a solid foundation of familiarity with art. Richards attended Eton College, the elite boarding school for boys with a long tradition of producing prime ministers and CEOs. There his teacher, John Booth, took groups of students and guest painters on summer trips to Florence to paint outdoors in the streets and the Tuscan countryside. Richards says, “In the evenings, you’d put the work up and have a glass of wine and the artists would talk about it. I thought, ‘This is amazing, I want to do this forever.’ When I was 15, I realized I wanted to be a painter and live in Florence.”

Upon graduation, Richards spent a year in Florence studying under Cecil, then enrolled in the art history program at Scotland’s University of St. Andrews. In 1999 he visited three important painting exhibitions in London — Rembrandt, Van Dyck, and Sargent — a powerful experience that steered him toward a career in portraiture. Richards recalls studying the Rembrandt portrait from London’s Kenwood House and thinking that the person in it was more interesting than any of the real people in the room. He was fascinated. He observes, “Paint became someone. Paint became flesh — it was a transubstantiation. This was actually a person.”

Yet Florence had captured his soul, and Richards returned to Italy immediately after graduating from St. Andrews; he was offered a job teaching at Cecil’s studio/atelier. There he met Richard Serrin, Daniel Graves’s first teacher in Florence. Serrin hammered home the idea that figurative paintings must be more than faithful renderings of what we see — they must also trigger some reaction in the viewer’s heart or mind. “He really encouraged me,” Richards says. “I want to honor him.”

Richards cites an anecdote about the 18th-century English writer Samuel Johnson, who was notoriously blind to the pleasures of art, but once wrote warmly to his painter friend Joshua Reynolds that the beautiful thing about a portrait is that it creates friendship in the present tense, sustains the bond when two friends are apart, and reminds us of friends after they have died. Richards feels “that idea of the three tenses, and that idea of a really meaningful relationship built up over time, is such a precious thing.”

Perhaps it is because Richards pays such close attention to that mysterious friendship that passes between a painting and its viewer that he is so in demand as a portraitist. He has had some remarkable clients, including a Hong Kong multimillionaire who commissioned an entire series of portraits. The trustees of Oxford’s Balliol College asked him to paint Donald Harris, the law professor remembered for championing the idea that the law has moral and ethical implications beyond its theoretical foundations.

Sources and Aspirations

The Florence Academy of Art is a few short miles from the golden heart of the Renaissance, where Botticelli painted Primavera, Michelangelo sculpted David, and Leonardo began his wrecked “Battle of Anghiari.” Its neighbors include the glorious galleries and frescos of the Uffizi and Palazzo Vecchio, among the world’s greatest art collections. Why, then, does the academy focus on techniques promoted by the leading art school in 19th-century Paris?

Richards replies: There isn’t that much really solid written evidence of a comprehensive program before the very end of the 18th century. You have fragments of things, but there isn’t the idea of a training manual. But the painters that most of us are interested in worked in the 17th century and earlier, so we use the 19th century as a prism to get back, to find connections to the art we really love. The 19th century is a guide, and the earlier art is an inspiration.

Having said that, the academy isn’t stuck in the reactionary mud of a Luddite past. Lest we imagine that formal imitation is the only goal, Richards is clear that students are instead devoted to emulation — learning from the Old Masters while improving upon their excellence, carrying the tradition forward into the future.

He explains: Tradition by itself is one of the worst reasons to do anything; otherwise you’d risk blindly carrying on with apartheid or something ghastly like that. Tradition has to be useful, to have a function … Nostalgia can be a great excuse for not doing anything or perpetuating evil. I don’t think the past is a mythically better place. I love the paintings of the 17th century, but I wouldn’t want to live then.

The academy’s three-year certificate course provides excellent skill-based training, from which students emerge with technical proficiency but without having yet had time to concentrate on independent work. “It’s like having great hand-writing, but not writing a book,” Richards notes. He expects that the M.F.A. program he hopes to inaugurate next year will fill that gap, giving students time and space to develop their vision as individual artists, guided by the faculty and by authorities outside the academy.

A group of smiling students rattles across the sunny courtyard into the cafe, talking of paint and pigments, gesso and glue. The espresso machine fills the air with a whoosh and the scent of fresh coffee, and Richards smiles: “You walk into the courtyard in the evening and there are a hundred people from 35 countries all doing their best. To see this global interest, this youth, this enthusiasm — it’s such an important thing. It’s pretty hard to be pessimistic.”

About the Author: Michael J. Pearce is a writer, curator, and critic who champions skill-based art that emerges from popular culture and shapes the spirit of the age. He has published dozens of articles, authored Art in the Age of Emergence, and is professor of art at California Lutheran University.

View related articles on Daniel Graves here at RealismToday.com.

***

Published six times per year, Fine Art Connoisseur is now a widely consulted platform for the world’s most knowledgeable experts, who write articles that inform readers and give them the tools necessary to make better purchasing decisions. Fine Art Connoisseur‘s jargon-free text and large color illustrations are attracting an ever-growing readership passionate about high-quality artworks and the fascinating stories around them. Subscribe here.

Tom Richards’ paintings are beautiful, best, beyond realism. Truly amazing. The students of Florence Academy will be blessed!

Comments are closed.