The following article draws from an art exhibition that took place in 2016; the information on Chinese academic drawing and the accompanying art is still relevant. Please enjoy.

The National Art Museum of China (NAMOC) in Beijing hosted The 2016 National Art of Sketch Exhibition (1), a project that gathered nearly 300 drawings produced over six decades by teachers and students from nine leading institutions, including the Central Academy of Fine Arts (Beijing), China Academy of Fine Arts (Hangzhou), Academy of Fine Arts of Tsinghua University (Beijing), Xi’an Academy of Fine Arts, Luxun Academy of Fine Arts (Shenyang), Hubei Academy of Fine Arts, Tianjin Academy of Fine Arts, Guangzhou Academy of Fine Arts, and Sichuan Academy of Fine Arts.

Made in China: Where Academic Drawing is Alive and Well

By Petra ten-Doesschate Chu and Liang Shuhan

The National Art of Sketch Exhibition was an eye-opener for those unfamiliar with Chinese practices: it revealed not only that academic drawing remains a cornerstone of art teaching, but also that it has reached levels that exceed historical and present-day norms in both technical ability and subtlety of interpretation.

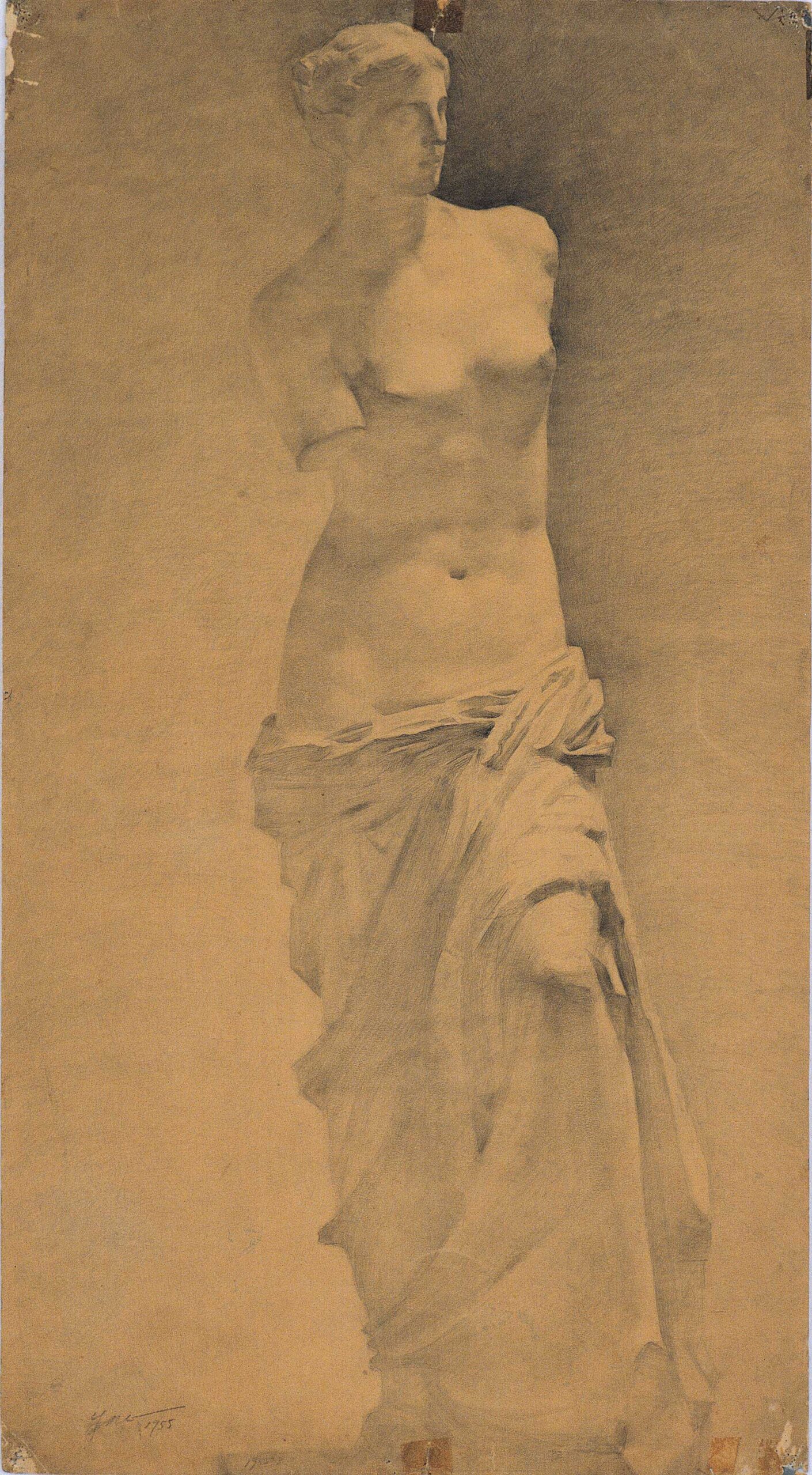

Li ZhiYu’s “Torso” is a useful example. It depicts a plaster cast of a lost Hellenistic masterwork that has long been a staple in academic ateliers worldwide: over the centuries, the “Torso Belvedere” has been drawn by thousands of artists ranging from Peter Paul Rubens (c. 1601) to Pablo Picasso (1892).

Li ZhiYu’s beautifully executed drawing differs from theirs by the addition of a blanket around the torso’s waist, held in place by several ropes. This adjustment stresses the belatedness of this artistic model — a plaster cast of an ancient sculptural fragment — which seems to have been pulled out of storage, where it languished for an indefinite period. Yet, even as the blanket and ropes stress the “object-ness” of the torso, they seemingly bring the sculpture alive, to become a “body,” with the ropes’ compression of flesh lending a strongly erotic quality.

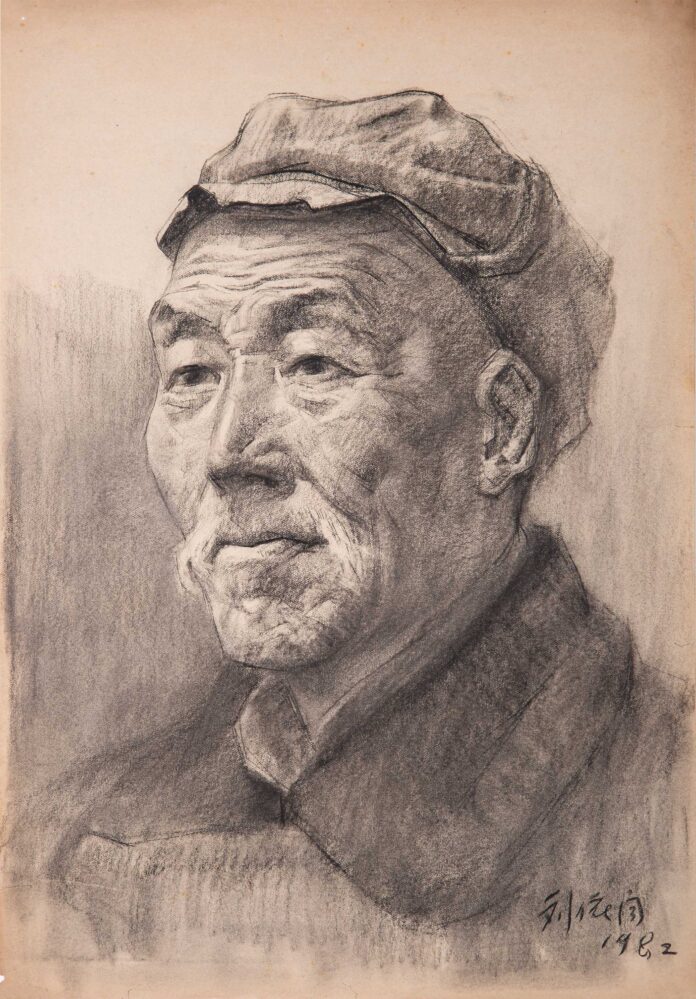

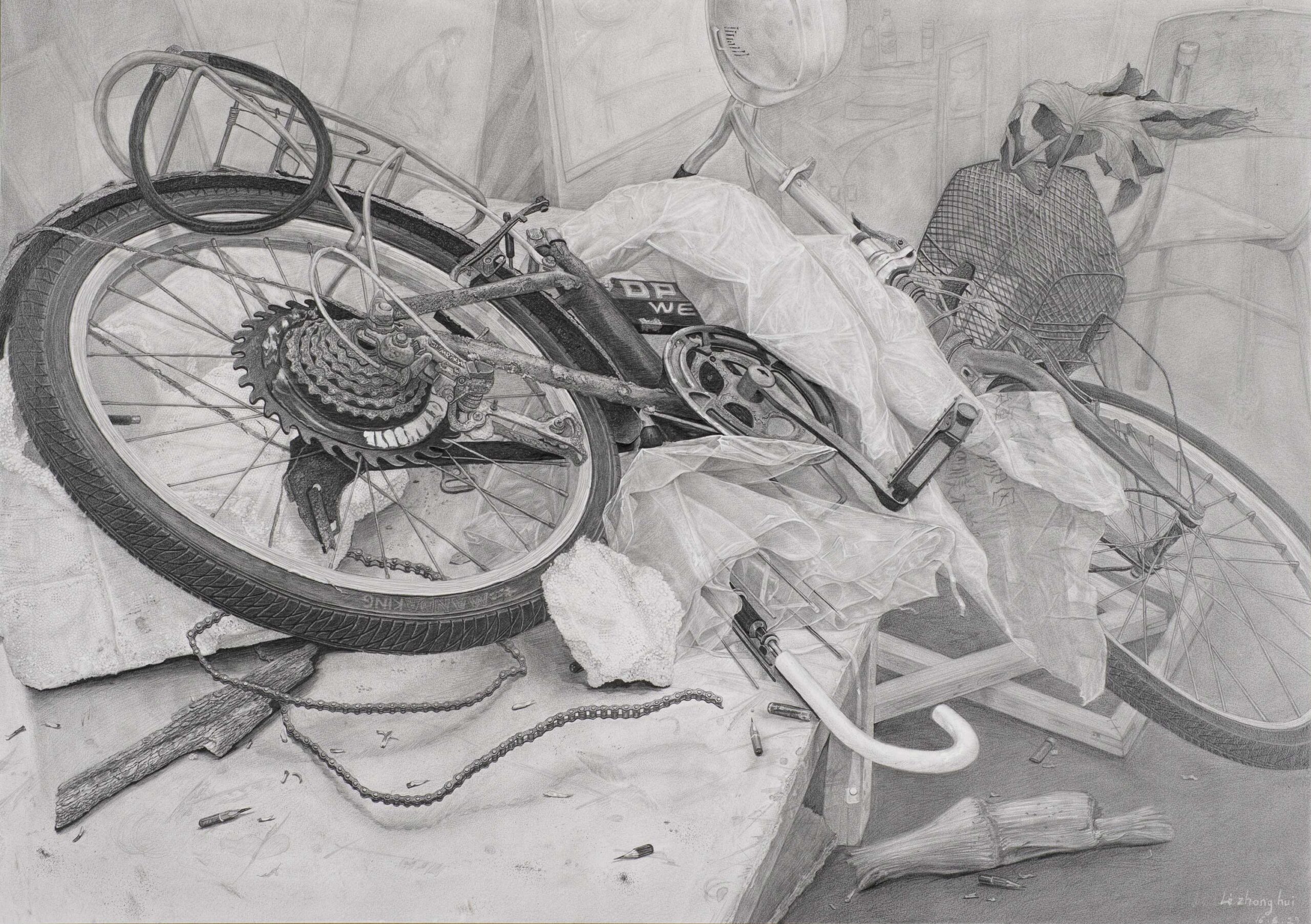

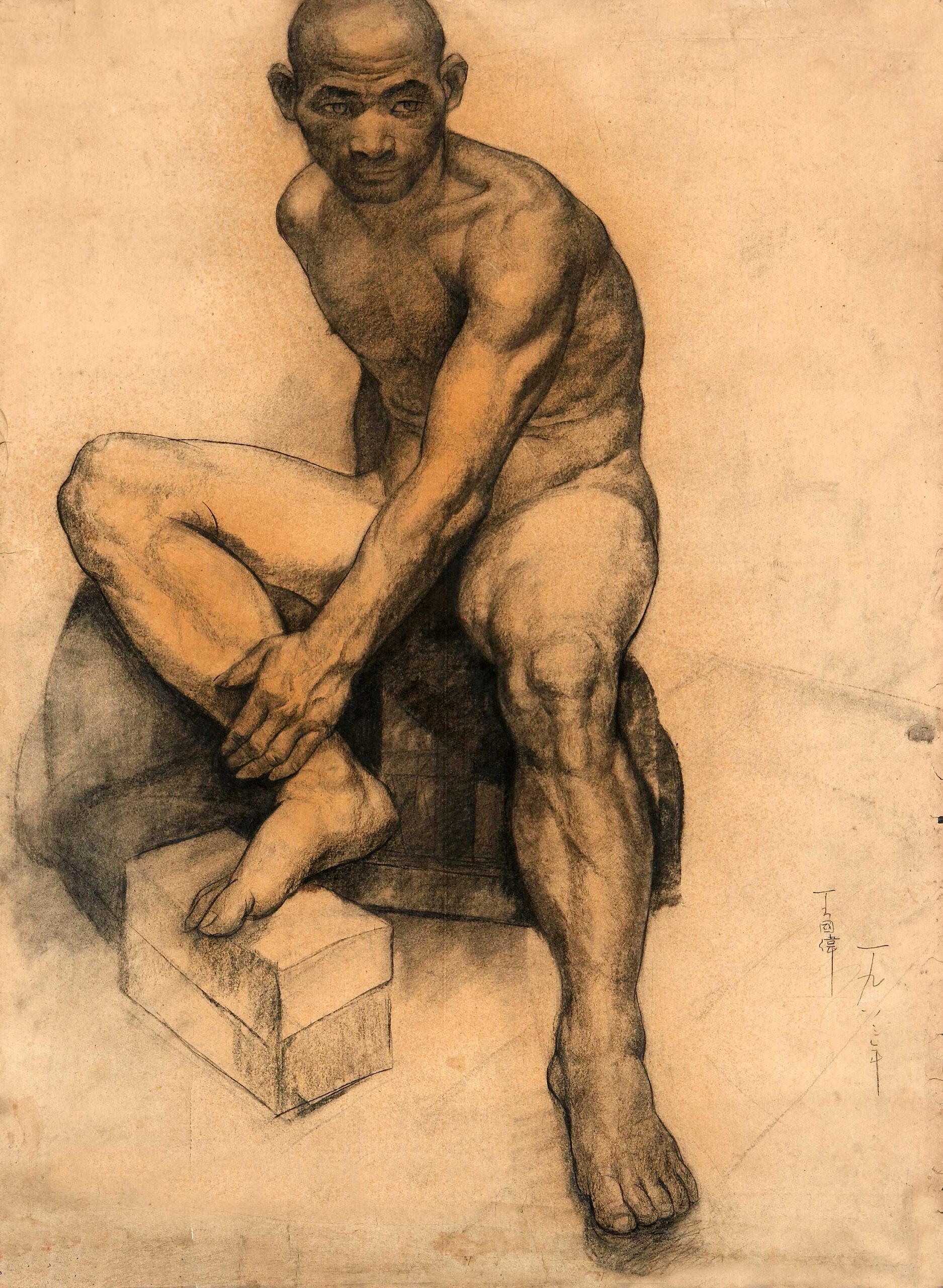

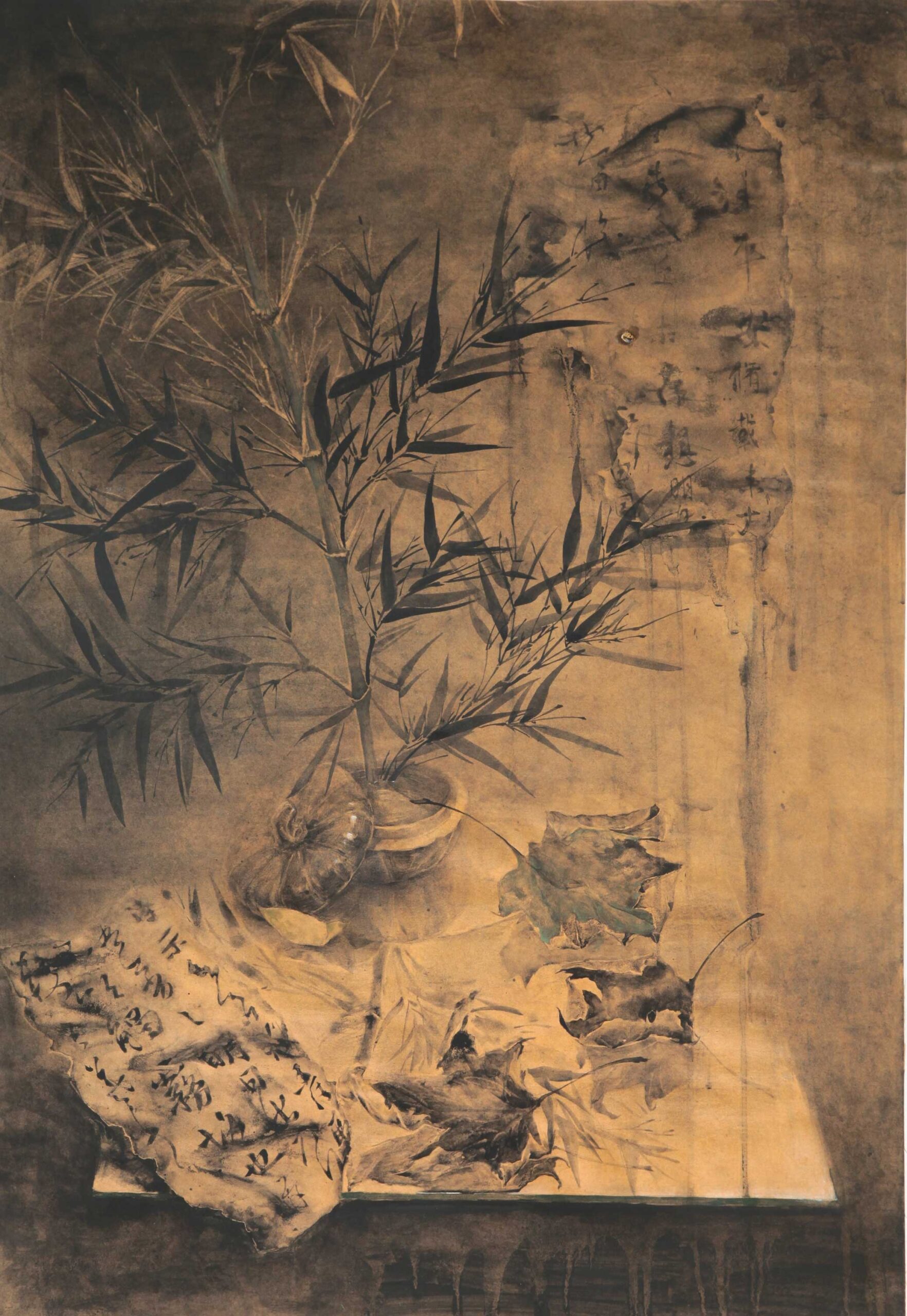

In addition to drawings of antique and 19th-century plaster casts, the NAMOC exhibition included life drawings, head studies, and still lifes. All were the products of keen observation and superb skill, focused in particular on the subtle rendering of value contrasts. Among the still lifes, Li Zhonghui’s “A Never-Ending Legend” was noteworthy. Showing a bicycle lying on a sidewalk, half-covered by a plastic rain poncho, it is not only a technical tour de force but also an intriguing glimpse of modern life.

A 20th-Century Phenomenon

In China, almost anyone with a standard art education believes that drawing is the foundation of all fine arts, yet drawing did not figure in a traditional Chinese art education until approximately a century ago. Beginning in the early 20th century, interest in drawing sprang from the desire to reform traditional Chinese art.

In his “Travels in Eleven European Countries” (1905), the political thinker and reformer Kang Youwei (1858–1927) wrote, “Compared to Western art, Chinese art is sparse and shallow. This matter should be the subject of reform.” Impressed by the techniques of the Italian Renaissance masters, Kang noted, “In terms of painters, I particularly prefer Raphael, whose depiction of nature is extraordinarily realistic”; he advocated assimilating the realist component of European painting into a reformed Chinese art (2).

Kang’s ideas had a profound influence on subsequent reformers. As early as 1902, the Liangjiang Normal School, created by the Qing regime, had established drawing classes, but, as no Chinese instructors were trained in drawing yet, it had to hire Japanese tutors.

Li Shutong was the first Chinese artist to teach Western-style drawing. On his return from studying in Japan in 1910, he introduced figure drawing classes at the Zhejiang First Normal School. He was followed in 1912 by Liu Haisu, who, at age 16, co-founded the Shanghai Academy of Chinese Painting (Shang Hai Tuhua Meishu Xueyuan). Convinced that the most important inspiration for painting is the human body, Liu was the first Chinese teacher to employ a nude male model (in 1914); soon after, female models appeared in his classrooms. In 1917, Liu’s students held an exhibition of more than 50 works, including figure drawings, which aroused a violent reaction from conservative commentators. Liu was called a “traitor of art,” a phrase he later used proudly to describe himself.

Though Liu Haisu was important, the key reformer of Chinese art education was Xu Beihong, who became the first president of Beijing’s Central Academy of Fine Arts (CAFA) after the People’s Republic of China was founded in 1949. Xu’s ideas not only influenced the educational program of CAFA, the country’s most prestigious educational institution, but also played a major role in developing the nation’s art education system generally.

While studying in France during the 1920s, Xu had ignored modernist trends in favor of studying with the elderly academic realist painter Pascal Dagnan-Bouveret (1852–1929). Upon his return, he called for a reform of Chinese painting through an infusion of Western-style realism. Most of his ink paintings (such as his famous horses) reflect a marriage of such realism with Chinese tradition. Xu’s proposals for restructuring art education were received more positively than Liu Haisu’s had been, and soon his ideas became mainstream. Indeed, those who clung to traditional Chinese principles were criticized for continuing to produce the “black paintings” of feudal society, particularly during the Cultural Revolution (1966–76).

The institutionalization of realism (especially Social Realism) as “official art” had much to do with China’s rapprochement with the Soviet Union. In 1955, when diplomatic relations were friendly, the Soviet realist painter Konstantin Mefodovich Maksimov (1913–1993) was sent to CAFA to reform its curriculum. His “Maksimov Oil Painting Training Course” had a far-reaching influence on China’s education system and on the direction in which official art moved. Its realist style was not necessarily preferred by CAFA students, but it certainly served the needs of China’s ideological propagandists.

Among the most successful Maksimov followers were Jin Shangyi (former president of CAFA), Hou Yimin (who later designed two editions of China’s paper currency), and Zhan Jianjun. All of the important artists active in official art institutions today are somehow affiliated to these three artists; at the very least, they were trained in the realist drawing methods this trio promoted.

Practical Concerns Today

As new artistic modes have emerged in China, drawing — essentially a training method for realism — no longer seems as important, yet art students still hold Xu Beihong’s dictum (“drawing is the foundation for all fine arts”) as an absolute truth. This is because drawing has assumed the role of upholding art’s prestige and artistic standards.

Accordingly, if a youngster wants to become an artist, or to engage in any field related to the visual arts, he or she must enroll in “boot camp” training courses in drawing and color one year before graduating from high school. The reason is that drawing and color both feature prominently in the entrance exams of the leading art education institutions. Of the two, drawing is more important; that’s why many test-prep courses offer color training only on weekends, while drawing is taught throughout the week.

To be frank, one cannot say that more high school students fall in love with art than did a generation ago. Rather, art has become a useful pathway in a hugely competitive arena: universities’ academic requirements for prospective art students are at least one-fifth lower than those in other disciplines, so tens of thousands of youngsters take the “boot camp” training courses less out of personal interest than to fulfill the dream of gaining admission to a university — a dream that was rarely fulfilled by their parents or grandparents (3).

Once admitted to an art academy or university art department, students enroll in grueling drawing courses, lasting more than 10 hours each day. They generally begin by practicing geometric shapes, still lifes, and plaster casts of facial parts (such as ears and noses). For the first two years, one is usually not assigned a major but remains in the foundation department to continue the study of drawing, which progresses from live heads to half-lengths to the entire body (nude and clothed), culminating with two figures. The ultimate goal is to train artists able to execute artworks with grand socialist subjects that serve the regime’s ideological purposes.

Fine arts schools have long been subdivided into departments of Chinese painting, oil painting, printmaking, and sculpture. Although newer areas such as “experimental” and “cross-media” have emerged since 2000, they remain relatively rare, and even artists working in performance, video, or installation probably started their careers in one of the four customary departments.

In any case, drawing remains an important factor in entrance exams for everyone. The reason for this is mostly practical. Faced with enormous quantities of applications, teachers must evaluate thousands of exam projects each day, making it impossible to judge students’ concepts or creativity. Drawing skill is, therefore, the most objective and effective way of evaluating students’ ability.

Even if Chinese academic drawing has remained largely the same for the past century and changes within art education are so minor as to be undetectable, new elements have emerged in students’ class assignments. Since the 1980s, some contemporary subjects and concepts have penetrated the otherwise rigid drawing curriculum. The drawing of a bicycle by Li Zhonghui, who currently studies at Sichuan Art Academy, is a telling example. Now a common prop in classroom exercises, the bicycle first emerged as a subject in the 1980s, when urban youngsters started to acquire their first bikes. At the beginning of China’s Opening and Reform era (1979), urban hipsters would often ride their bikes in groups, with guitars on their backs and a cassette recorder in their hands, hanging out in the suburbs or on city squares. The bicycle thus became a symbol of youth, freedom, and artistry. Moreover, its complex physical structure makes it an ideal test of the artist’s technical skills.

The greatest significance of academic drawing in China today is its capacity to uphold standards, quantifying and systematizing skill at every stage of an artist’s development, be it during an entrance exam or when the time comes to appoint or promote art instructors. (Most Chinese artists also teach at universities or academies.)

Surveying this situation, we may recall Henri Matisse, who wrote, “When the means of expression have become so refined, so attenuated… their power of expression wears thin.” (4) That may be true, but even so, the recent exhibition at NAMOC proved that individual expressiveness sometimes shines through, even in drawings of the most traditional subjects executed in the most rigidly circumscribed manner.

About the Authors

Petra ten-Doesschate Chu is a specialist in 19th-century European art, a field in which she has published extensively. She is a professor of art history and museum studies at Seton Hall University (New Jersey). Liang Shuhan is a lecturer in art history and art criticism at China’s Tianjin Normal University. He previously worked as an editor and translator at the Chinese website of ArtForum magazine.

Endnotes

(1) It took place September 23–October 8, 2016. NAMOC exhibits modern and contemporary Chinese painting and sculpture in both Chinese and Western styles.

(2) Kang’s Travels, published in 2007, were based on notes he took during a 1905 trip to

Europe. All translations are by Liang Shuhan.

(3) Higher education was once virtually free, but since the late 1990s, tuition fees have

become a key revenue source for universities. Art school fees are generally double those paid by humanities students.

(4) Jack Flam, Matisse on Art (Berkeley and Los Angeles: University of California Press, 1995), 122.

Become a Realism Today Ambassador for the chance to see your work featured in our newsletter, on our social media, and on this site.