A look at the history of portraiture, the process of doing a portrait commission, and the challenges you might face.

Making Faces: The Ups and Downs of Portraiture

By Daniel Grant

What characterizes a great portraitist? It starts with the ability to catch a likeness, a keen sense of anatomy, and accuracy in flesh tones (for painters) or setting of the eyes (sculptors). These are art-school competencies, but there is an additional skill that differentiates the great from the good.

This is the gift for conversation. It means knowing what to say when introduced to prospective clients, then telling them what the portrait will cost without losing their commission. Later there’s the dialogue to pursue if sitters feel uncomfortable being stared at, start to sag, or prove to be unlikeable. And finally, there’s how to respond if they want changes made to the completed work.

On occasion you meet a portraitist out in the world — Andy Warhol often attended parties full of wealthy people and returned home with commissions — but most folks learn about portraitists through word-of-mouth. Another key method is contacting a specialist agency such as Portraits, Inc. or Portraits South. These firms present prospective clients with work samples from the artists they represent, then draw up a contract to formalize the commission.

Alternatively, galleries that handle figurative art are often asked if one of their artists might be commissioned to make a portrait; these dealers then serve as intermediaries, fixing (and splitting) the price and scheduling payments, sittings, and the unveiling.

A COMPLICATED TRADITION

Portraiture has a long history and was advanced enough by Aristotle’s time for him to identify three categories — the idealized image, the exact likeness, and the caricature. Through the centuries, a patron’s likeness might appear somewhere in a historical or religious scene, but from the Renaissance onward, portraiture became its own genre thanks to humanism’s new recognition of men (and a few women) as individuals rather than merely God’s creations. As artists became noted in their own right, self-portraits (and portraits of other artists) grew worthy of attention, too.

From Masaccio to Alex Katz, the roster of artists who have created portraits is long and impressive. Yet for many of these talents, there was and still is a stigma attached. John Singer Sargent, who remains best known for portraits, called them “putrids,” and today some artists bristle if introduced as portraitists.

For others the term smacks of commercialism, of pleasing the patron and not oneself. Brandon Brame Fortune, chief curator at the National Portrait Gallery in Washington, notes that Alice Neel “didn’t think of her paintings of people as portraits, which they clearly were, because she saw portraits as something that were paid for and meant to flatter.” (In fact, Neel’s likenesses were seldom flattering.)

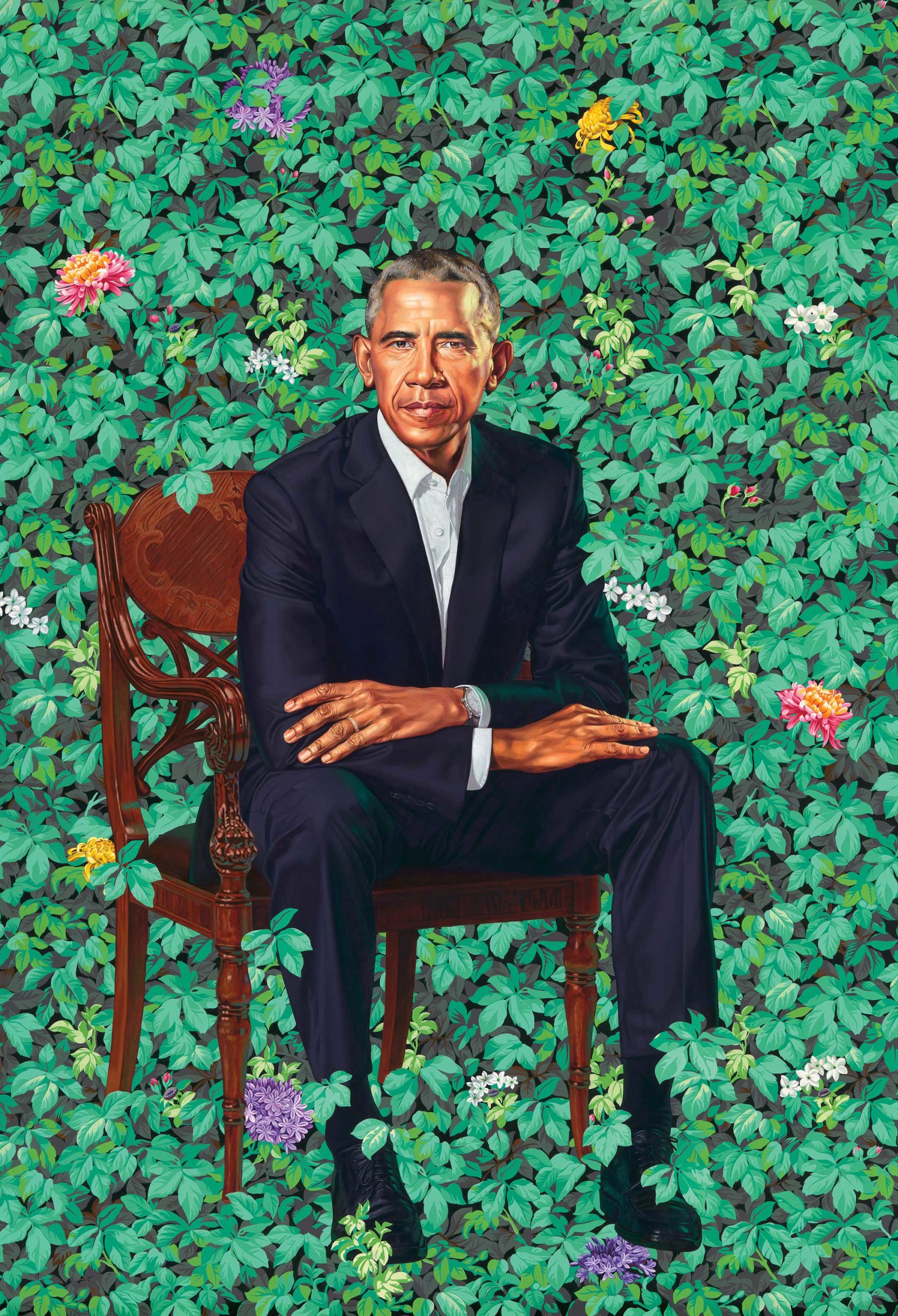

Technically, Neel was correct: portraits are paid for, and they tend to present the sitter in a positive light. That lurking perception of portraitists as second-class artists may be why Kehinde Wiley, who painted President Barack Obama to huge acclaim in 2018, “almost always says ‘no’” when asked to do a portrait, according to Janine Cirincione, director of New York City’s Sean Kelly Gallery, which periodically fields such requests for him. “He sees himself as a conceptual artist who happens to focus on people,” she explains.

Nothing says luxury and extravagance like commissioning portraits, especially because they almost never have a resale value. Who — one might ask — wants a no-longer-needed image of someone else’s ancestor or boss?

There are exceptions, of course. Portraits by Sargent and Warhol trade for high prices, and what is perhaps the world’s most famous artwork, Leonardo’s “Mona Lisa,” is actually a portrait of the wife of a wealthy Florentine merchant (long-forgotten himself ). Clearly, then, a portrait can stand on its own as art, and its subject’s reputation is not necessarily essential to appreciating it.

THE PROCESS BEGINS

Today, the cost of commissioning ranges widely, from several thousand dollars (pet portraits are in this tier) to several hundred thousand dollars (for large, full-figure likenesses with background imagery). Payments are usually scheduled on the basis of one-third when the contract is signed, one-third when the client approves the image halfway through the process, and the last third within 15–30 days of final delivery. (Some contracts skip the middle stage in favor of half-and-half.) Artists without representation must discuss pricing directly with prospective clients, while those who were introduced by an agency or dealer are largely spared that negotiation.

But not always. Robert A. Anderson, a 74-year-old painter in Massachusetts, gets most of his commissions through Portraits, Inc. But if someone at a party asks how much he charges, his prices (averaging $60,000 for a three-quarter-length measuring 40 x 30 inches) may make the questioner balk. “I tell them, ‘If I’m not in your price range, I know a lot of portrait painters who will give you good value for what you want to spend.’ That’s my soft sell. It makes people feel that I am honest and not just after their money.”

Once the contract is signed, the real talking begins. The Connecticut-based sculptor Marc Mellon (68) starts by discussing his process of modeling clay. He prefers a “looser” style (rougher edges) to a “tighter” one (smoother), but can accommodate the wishes of his client. Before the clay model gets cast in bronze, there is a conversation about patina, the protective coating that may be green or brown. “I send samples of different patinas to see what they prefer,” Mellon notes. “Some people have opinions such as ‘I want it to look like the patinas Rodin used,’ but most don’t really know what the differences are, so I explain the choices and how they affect the way the bust will look. They generally are appreciative of being brought into the decision-making.”

A portrait isn’t just a likeness, though it should look quite like the subject. It is a work of art, created by an artist and reflecting her or his sensibility and understanding of the sitter. That understanding takes time to develop and often starts before the first meeting, such as with a Google search or trip to the library. If the sitter is particularly well-known (for instance, a politician or corporate CEO), portraitists may read up in advance. Such research informs the artist’s vision and gives the pair something to talk about if nothing else arises during their hours together.

The purpose of that conversation is to distract sitters from what’s actually going on, from the fact that they are being stared at. This might make anyone self-conscious, especially a VIP more accustomed to being listened to than examined for skin blotches and protruding ears. In 2005, the singer Tony Bennett came for a sitting in Mellon’s studio. For this occasion, the artist “upgraded my sound system, and I played the American song book, sung by people he knew.” Hearing that music kept Bennett cheerful for the whole two-hour sitting. “He told me stories about this buddy, that old friend.”

Edgier portraits generally reflect a stronger sense of interpretation on the artist’s part. The Canadian photographer Yousuf Karsh’s most famous image is a 1941 portrait of British prime minister Winston Churchill grimacing at the camera and, really, at Karsh himself. The artist later claimed that, just before he snapped, he grabbed a cigar out of Churchill’s mouth, angering him but giving him the look of determination for which he was renowned. Going further was Diane Arbus, who snapped photo after photo until her sitters lost their composure and presented an appearance far more authentic.

From a safe distance, we appreciate the bold innovations of such artists, but sometimes they are not applauded. Paul Emsley, whose likenesses of the author V.S. Naipaul and anti-apartheid activist Nelson Mandela hang in London’s National Portrait Gallery, painted a 2012 portrait of Kate Middleton, the Duchess of Cambridge, whose smile more resembles a smirk.

It drew withering scorn on both sides of the Atlantic, with one writer disdaining its “sepulchral gloom” and another calling it a “mawkish book illustration.” It scarcely matters that the sitter’s husband, Prince William, called the portrait “absolutely beautiful,” an assessment with which his wife agreed. Perhaps they were just being polite?

Most portraitists prefer not to ruffle feathers. Often they are called in when a leader retires from a corporation, institution, or political post, fully aware that the new portrait will appear alongside those of his or her predecessors. It will probably be the same size, to avoid suggesting one person is more significant, and will probably look a bit like the others, too.

Decades of experience may well be poured into a likeness that few viewers ever look at seriously. The late Daniel E. Greene (1934–2020), who lived just north of New York City, noted that most of his commissions “are relatively traditional, and I know exactly what to expect.”

CHALLENGES GALORE

Keeping the conversation going is vital to ensuring that the result, if not an artistic breakthrough, is not a disaster. Many sitters are older people who may become sleepy when inactive for extended periods. Gilbert Stuart, renowned for his portraits of our country’s first president, wrote that “a vacuity spread over [Washington’s] countenance” as soon as he began to pose, so the artist sustained a steady patter to keep him alert.

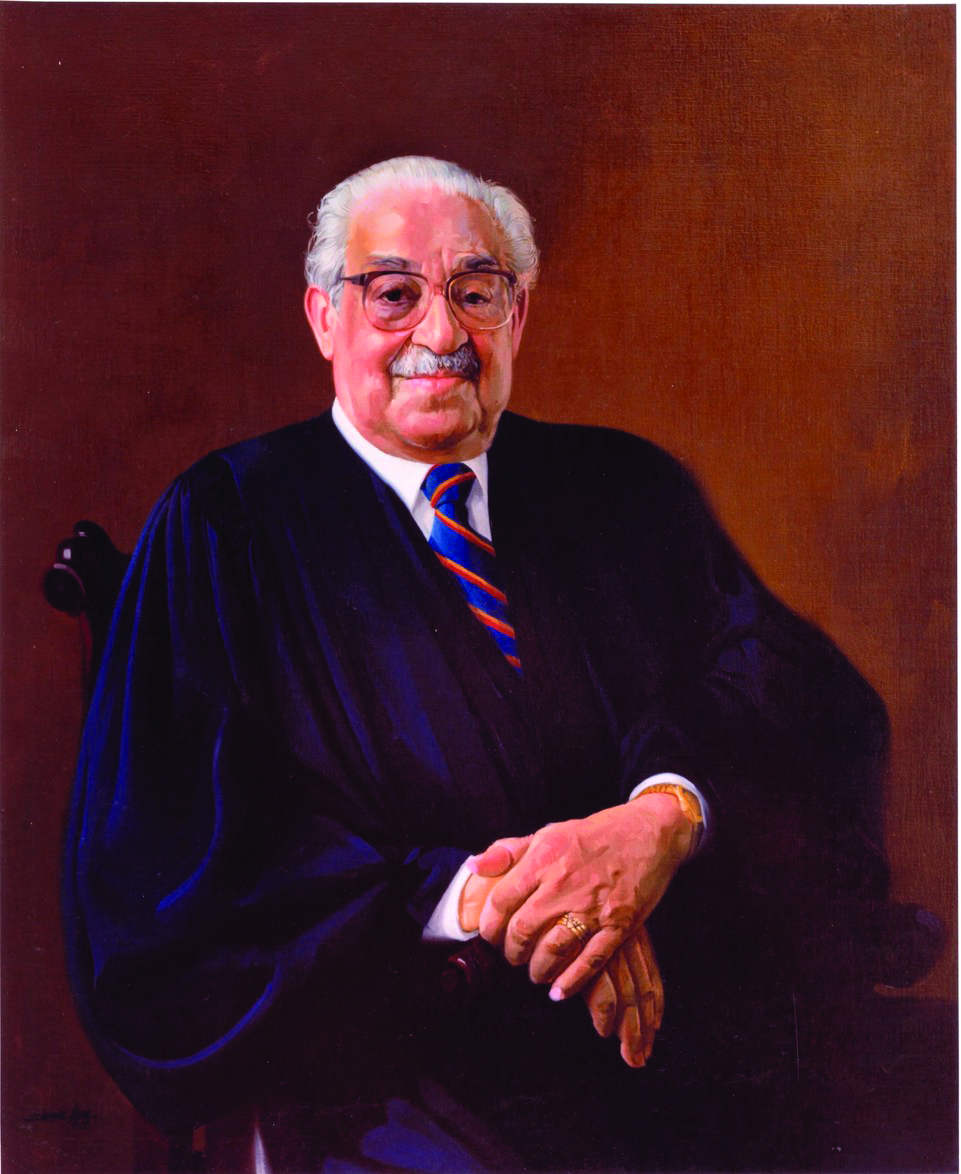

In 1982, while sculpting a bust of Vice President George H. W. Bush (now at the National Portrait Gallery), Marc Mellon found that the longer his subject sat still, the more his face sagged. “Sitting for a portrait may seem like downtime to busy people,” he notes. “Whatever needs to get done tends to filter up, and so you see a certain worry in the face. You see the weight the person feels he’s carrying. You as a portraitist must be aware of this, because you’re no longer seeing the public face, but the private one, the one Mrs. Bush may see when the vice president brushes his teeth in the morning. You have to find ways to get back to the person who is going to be portrayed.” Put another way, “You want to paint not the wizened old guy in front of you, but the guy who built the company,” says Jacob Collins, who charges $100,000 per portrait.

Many portraitists get their clients at the end of a tenure, when they are less energetic (and perhaps less hopeful); it is the artist’s job to recapture some of the dynamism. In his first year as president, Jimmy Carter was told by the White House curator that he should have his portrait painted right away “while you are still good-looking.” But like most of his predecessors, Carter waited until after he had left office, presenting a more weathered version of himself to the painter Herbert Abrams.

Parents can be difficult clients when commissioning portraits of their children. When Sargent was asked why he reworked the face of a young woman 15 times, he replied, “She had a mother.” This is especially true if the portrait (of a person of any age) is posthumous. In that case, the artist works from photographs, and different survivors may have competing images they want represented in the final work. The portraitist needs to know at what age the subject will be depicted, and also what aspects are to be brought out (e.g., business suit or golf shirt?). Mellon stresses the need to determine, “from the get-go, who is approving the commission: a committee? The head of the company? The widow?”

Related Article on Portraiture: How to Create a Vibrant Posthumous Portrait

This wisdom came to Mellon the hard way after he was asked to create an eight-foot-tall statue of Dr. Alton Oxner, commissioned posthumously by the Oxner Medical Center in New Orleans. A committee of the center’s directors provided photographs of Oxner, most taken later in his life. They had approved the small- and full-size models, and Mellon was ready to cast when Mrs. Oxner unexpectedly visited his studio.

Dissatisfied with the work, she asked how he had picked that pose and expression, at which point the artist showed her the photographs. “Oh, I’ll give you better photographs,” she replied, and soon supplied Mellon with pictures taken 20 years earlier. The changes required were extensive, not only to the head, “but also to the whole carriage,” Mellon recalls. “A man in his 60s holds himself very differently than one in his 80s.” Fortunately, “adjustments were also made in the budget” to cover the necessary time and labor.

Chit-chat, and perhaps more substantive conversation, are in the portraitist’s toolkit, but sometimes the artist must do more. “Years on the job put these people through a lot of stress,” says the 84-year-old Maryland painter Simmie Knox, “so I might give the person a little chin tuck or soften lines around the eyes. Clients never ask me to take pounds off, but I want to show them at their best.”

The clergyman and anti-war activist William Sloane Coffin, Jr., did ask Robert A. Anderson to trim 25 pounds off him, “but he told me that, if I did so, he wouldn’t embarrass me at the unveiling. True to his word, he had dropped 25 pounds by the time the portrait was unveiled.” The lost-youth question comes up early in conversations Mellon has with his sitters. “I’ll ask them, ‘Do you want me to see you as you are now, or roll back the clock some?’” Many of his clients bring along earlier photographs and tell him they want to look like that.

Most artists are willing to make adjustments. “The client has to be happy,” says Julia Baughman, executive partner of Portraits, Inc. Sometimes, though, it just doesn’t work out. Andrew Wyeth’s brother-in-law, Peter Hurd, painted a portrait of President Lyndon Baines Johnson, who called it “the ugliest thing I ever saw,” while Graham Sutherland’s vision of Churchill was never seen by the public because it was destroyed by Mrs. Churchill, who was even more incensed about it than her husband was.

For all the good that conversation brings, it can be tricky. Daniel Greene placed a large mirror behind himself so the sitter could see what was being painted. “Watching the image develop keeps their attention and has a magical quality for them,” Greene explained. However, he also learned — while painting the novelist Ayn Rand — to “limit involvement with the sitter. Explaining the process is one thing, but I don’t want to debate every brushstroke,” which actually took place with her on more than one occasion. Greene concluded, “I advise younger portrait artists to avoid soliciting the subject’s approval during the process.”

What the sitter says (about politics, for example) may not sit well with the portraitist, so the latter must respond in a way that straddles integrity and complicity. While sitting for Mellon, Bush “said he wanted to watch Meet the Press, and afterward we talked about environmental policy.” Fortunately, the conservative vice president “responded well” to what Mellon, a liberal Democrat, had to say.

People who may seem overzealous on television may be perfectly agreeable away from the camera. Greene discovered this while painting a right-wing pundit: during their time together “we did all we could to avoid controversial subjects.” Greene did not regret the commission, a full-length portrait that was “expensive” for the sitter. But he worried about being associated with the sitter, and so removed the name and image from his website.

For his part, Knox notes that, “I am an African-American, so some commissions I will never get, not because of my skill but because of my complexion. I understand that. If a person thinks enough of you to want you to do their portrait, you do their portrait. You are expected to rise to the occasion, even if you do not agree on many things.”

NEW ENERGY

The art of American portraiture has returned to prominence recently thanks to an unexpected success. In 2018, Kehinde Wiley painted a large oil of former President Barack Obama, while Amy Sherald made one of First Lady Michelle Obama. These have drawn record crowds to the National Portrait Gallery, and in 2021 began a five-city U.S. tour. Gallery director Kim Sajet says, “You can use these portraits as a portal to all sorts of conversations,” which is exactly what the five participating museums plan to do. Princeton University Press has published a handsome, 140-page book about the project, complete with a reversible dust jacket that allows readers to choose which of the two portraits will appear on its cover.

Imaginative efforts like this — not to mention people’s ageless desire to see what other people look like — suggest that portraiture is here to stay.

Visit EricRhoads.com (Publisher of Realism Today) to learn about opportunities for artists and art collectors, including: Art Retreats – International Art Trips – Art Conventions – Art Workshops (in person and online) – And More!