In a good painting, love shines through like a star on a cold night. Unfortunately not everyone can see it, and therein lies the paradox.

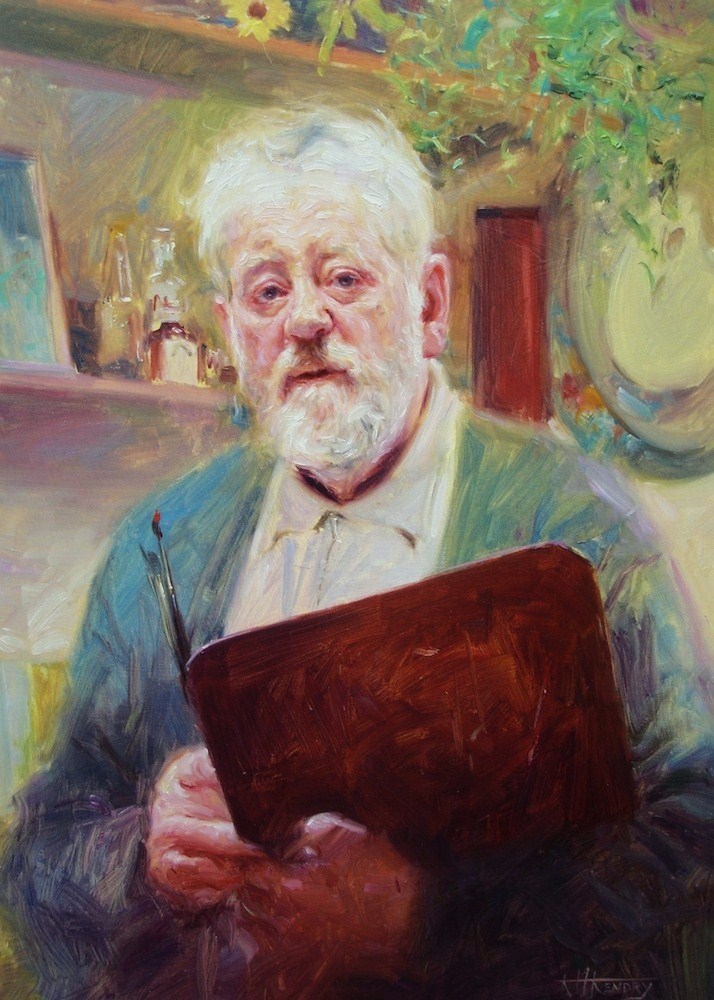

By Kenny McKendry

kennymckendry.com

George Inness, the great master of the Tonalist movement, defined the purpose of art as, “Simply to reproduce in other minds the impression which a scene has made upon one. A work of art does not appeal to the intellect. It does not appeal to moral sense. Its aim is not to instruct, not to edify, but to awaken an emotion.”

Indeed, as my fellow Irish painter Mark Shields puts it, “Presence rather than appearance is of primary importance.” To this end a good painting is either won or lost. It is there to be brought forward by the painter, to be placed within our world, conscious of time as a continuum. A meeting point between past and future. Formed by one and shaping the other, albeit perhaps in the simplest of ways.

I had always held Inness’ view; 13 years as an illustrator in my early career certainly tended to dull one’s edification of art, what with deadlines, instruction, briefs, roughs, etc. However, the older—and I hope wider—in mind I grow, the less I’m convinced of Inness’ view. Rather, good painting can instruct, appeal to moral sense and edify, as well as awaken emotion. It can do all these things, but along with Shields, I believe presence, above all, remains paramount.

And what do we paint? Light. Light is our subject. Light, or the absence of it in some cases. As Jon Redmond puts it, “Light is what we see, not things, light is the main focus.” With objects, landscapes, human form, the touching of light is what we paint. One’s prowess instructs how we do it; we all have our ways, techniques, or indeed habits. Like one’s handwriting, the individual painter will be just that: unique. Even if our methods are the same our work still has the mark of individualism.

Some fare better than others. There is somehow a “scratchiness,” as I put it, that can elevate a work above another. Is that a touch of Soul? A beautiful little area where the paint slides off the brush and twists just so. It is in such places that one finds spirituality in painting, or dare I say, love. Love in the wider sense of soulfulness—a symbiotic, intangible link between craftsmanship, hard-won experience and nature.

As the noble and simply honest painter William Langson Lathrop suggested, “The finest art, like all else founded in life, is founded in love. The presence or absence and the amount and quality of the love embodied in any work of art is the sure guide to its value and permanence.” I concur. His and my belief in the power and nobility of love is at the very crux of what we surely try to do.

In a good painting, love shines through like a star on a cold night. Unfortunately not everyone can see it, and therein lies the paradox. Andy Warhol once famously commented that he did not want to be a great artist—he just wanted to be a famous one. Beneath this flippant remark lies significant insight into how an artist can come to be valued. Some people, whether in the commercial arena or otherwise, may not trust their own judgment about artistic quality. Indeed, even as a painter, one’s barometer of one’s own efforts can swing too high or too low, only at a later date or in a moment of clarity to be reconciled with the work’s actual merits or deficiencies.

People may find comfort in knowing that others have already elevated an artist to a celestial pantheon. Sometimes fame, as Warhol sought, not substance, is the ultimate yardstick. When one is relatively unknown they may be considered of less importance or, at best, as yet “undiscovered.” I’m sure we all know of artists that we greatly admire who may be seen as mere footnotes in art history on a scale imposed by an unreal monetary value. As Douglas Fryer comments, in spiritual currency, “The value of art is dependent upon the intent and beliefs of the creator, combined with methods of execution appropriately fitted or contrived for the purpose of the full expression of the objective.”

Again, the presence, the love, as Lathrop suggested, in a painting is the true measure of its greatness. Excessive “realism” and detail, as I found with illustration, can clog up this process. One must constantly remain alert toward one’s potential tendency to stray in that direction. It can distract artist and viewer from the essential purpose of painting, a contained presence, a specific emotional atmosphere, man and nature linked in a symbiotic relationship in which the personality of man and the soul of nature are intrinsically woven together.

Consider the Barbizon painters, the American Tonalists—this symbiotic relationship is what I believe they achieved, as have many others before and since. The resurgence today of such ideals, skills and aesthetic—particularly in America—is heartwarming and exciting. Art is a massive, mystical subject. There is room for all artists to articulate with paint and brush, and for viewers to enjoy the nature of thoughtful engagement that their work elicits.

As the novelist Henry James said: “The enjoyment of a work of art, the acceptance of irresistible illusion, constituting, to my sense, our highest experience of ‘luxury,’ the luxury is not the greatest, by my consequent measure, when the work asks for as little attention as possible. It is greatest, it is delightfully, divinely great, when we feel the surface, like the thick ice of a skaters’ pond, bear without cracking the strongest pressure we throw on it.”

- Visit PaintTube.tv to learn how to paint portraits and figures in the style of contemporary realism, and much more.

- Join us for the next annual Realism Live virtual art conference and study with the world’s best realism artists.

- Become a Realism Today Ambassador for the chance to see your work featured in our newsletter, on our social media, and on this site.