From the Artists on Art archives, a feature article by David Kassan about “developing a state of mind, about being your own artist, about being who you are and bringing your own truths to your work, in the way that only you can.”

BY DAVID KASSAN

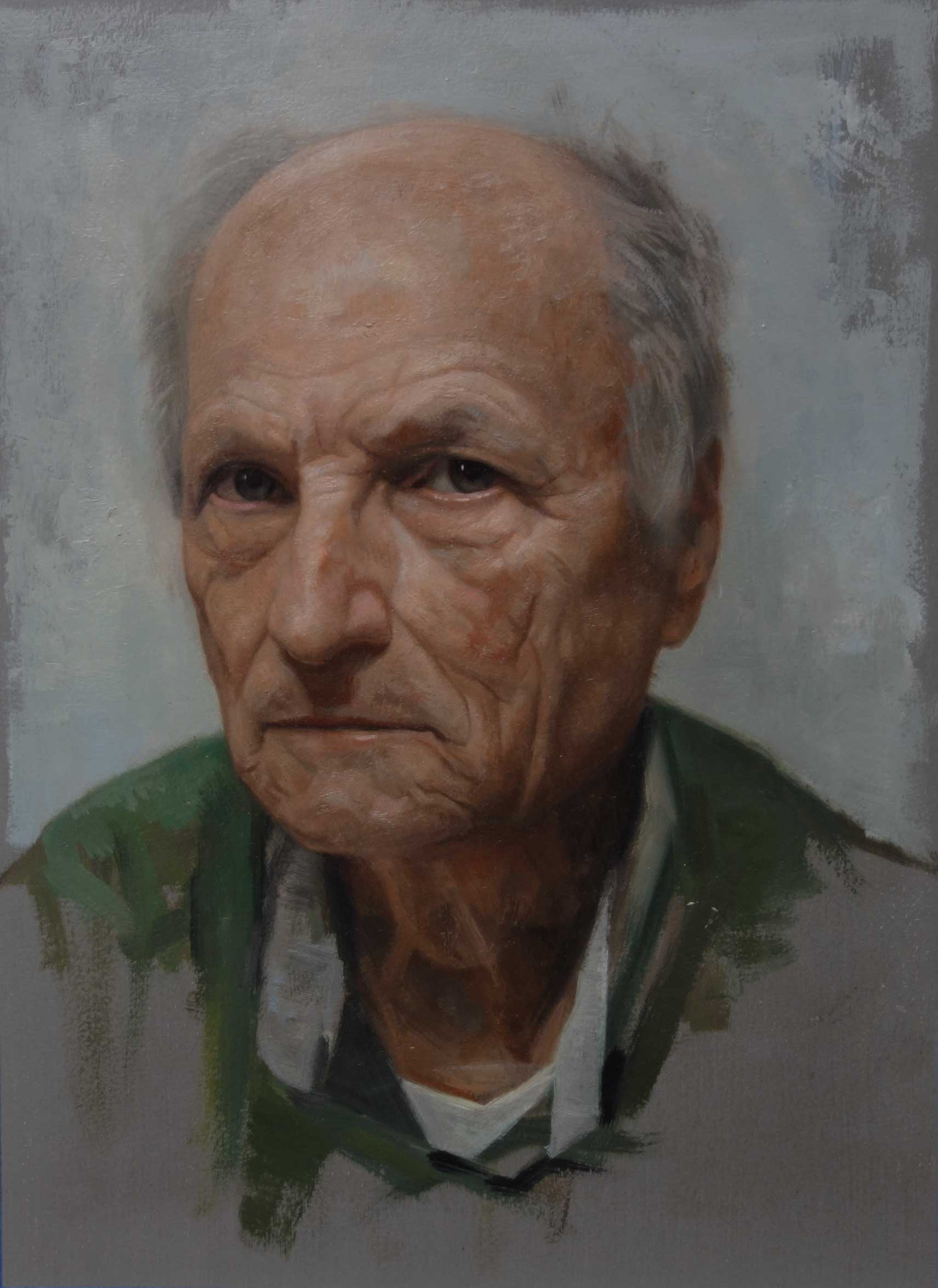

It is November 27, 2012. I’m in Antonio López García’s studio in Madrid, Spain, and the master himself stands before me, remarkably, as my model. My brush is tentatively placing little spots of color onto the painting surface. I’m pleased with myself. Not with the painting, but with the fact that I didn’t actually drop too many paint tubes as I clumsily added them to my palette.

I’m feeling a little rushed and I’m afraid to ask him to hold still. I have so much respect for this artist, and he is looking directly at me with the same intensity that he brings to his work. I’m confused about what I should say to him. Usually I talk a lot to my models, but my brain is frozen right now. I’m grasping for a better understanding of him, not only for the painting’s sake, but also for what I can learn about him in this short time.

From the start, I know that this quick alla prima painting doesn’t need to be good. It is just for me, no one else. I want to remember this moment for as long as I can—to turn this fleeting moment into a concrete memory, an experience that will stay with me. I have a very deliberate way of working, focusing on only what is in front of me.

About ten minutes into the painting session, Antonio says something loudly in Spanish and laughter fills the studio. I naturally smile even though I have no idea what was said. My good friend and translator Borja turns to me with a smile and says, “Antonio is fascinated with the strange shape of your ear.”

When Artists on Art asked me to do an article, I thought it would be the perfect publication to write about my experiences meeting and painting Antonio López García. Over the past couple of years a number of people have asked me how I was able to meet him and what he was like, as well as a number of other questions. It’s an experience that has always been really hard for me to summarize, because the story unfolded over a few years and only happened because of pure luck and the generosity of friendship.

It all started strangely enough with an email I received in 2006, from Borja, an aspiring artist in Europe:

Bonafuente Gonzalo,

Amazing. I have no more words. Amazing. That´s what I want to learn to do. Do you accept students in your studio? I´m from Europe but I will be in New York for 3 months from november to january. May I visit your studio please? Just to see it or something, I don´t want to disturb any of you. It´s really amazing your paintings.

Thank you for your time.

Borja

Fortunately, I get emails like this on a somewhat regular basis. They are incredible, especially for an artist who is pretty much a hermit when I’m in my studio, with all of the weaknesses and insecurities in my work that I’m struggling to overcome.

So many folks that you come across in life (family, friends, strangers) don’t understand what it is that we do, or how hard we work. They think it’s a hobby or they’re waiting for you to grow up and get a typical job. It is not their fault that they don’t understand the passion that we have as artists. As a result, I’ve really come to cherish and appreciate every kind word that is thrown in my direction.

Back in 2006 when Borja was visiting New York City, I had my studio in my home and had just welcomed a new addition to my family—a four-month-old baby named Lucas. I wasn’t really into having studio visits with strangers. I suggested over email that we meet at an exhibition opening or maybe a museum. A week or so after he arrived in New York, we met up at one of the Salmagundi Club shows and hit it off right away. He was super serious about painting and was really chill.

At this time I had the great fortune to teach once a week at the Cathedral of Saint John the Divine’s sculpture studio. The Cathedral is a huge gothic structure up near Columbia University on 116th Street and Amsterdam Avenue. Few people know that there is a huge art studio with thirty-foot-high ceilings in the cathedral’s crypt. The space is the working studio of artist Greg Wyatt. The studio was funded and run by a foundation, and they hired me to teach a drawing class there once a week.

At that time, I was really hungry for teaching jobs, especially with the new addition to the family. I was struggling to make ends meet and desperately trying to keep my painting career alive. I jumped at the chance to teach, even though it didn’t pay very well, and was a two-hour commute in each direction. I had to hire a sitter for an hour each class to watch my son, but the models for the class were all paid for, and the best part of the job was that the students could attend for free!

Once I saw how cool Borja was, I immediately asked him to join the drawing class. Over the next few months, we hung out a little together and I even had him pose for a drawing, which ended up on the cover of the Australian magazine EMPTY. We used to joke around, saying that you know it’s a small world when a Spaniard is drawn by an American and the drawing ends up on the cover of an Australian magazine.

Fast forward to July of 2009. I had received an invitation to teach in Faro, Portugal, where I had taught the previous year and fallen in love with the city, which is located right on the southwestern coast of the Iberian peninsula, in an area called the Algarve. Since I was already going to be in that part of Europe, I figured that it would be easy to first fly into Madrid and then train down to Seville and grab a ride over to the Algarve region. Faro was only a two hour car ride west from Seville, and the year before my buddy Nuno, who lived in Faro, said that the Portuguese in the Algarve regularly drove over to Seville to shop at the Ikea.

Having never visited Madrid as an adult, I planned for an extra five days to visit Borja, who was now living in Madrid. The last time I was there I was only three years old, but I’ve held on to the strangest fondness and memories of my trip there. They are almost like vague dreams.

My father was in the air force for 22 years, and in the late 70s and early 80s we were stationed at Ramstein Air Base in Germany. While we lived there, my parents’ goal was to see as much of Europe as they could. They would pack my two older brothers and me into a compact green Renault for long road trips to other countries, one of which was Spain. It is funny the things that stick in a kid’s head, but we happened to be there at Easter time and I participated in an Easter egg hunt, right outside of Madrid. I won a huge Tonka truck—well, at least it was huge to a three-year-old. It was so large in fact that we had to strap it to roof of the car. So since I was three, I’ve always loved Spain—the land of enormous free toys, and it goes without saying that by default, I was super-psyched to drop in on Spain again.

I arrived early in the morning, since it is my practice to take redeye flights so I can sleep on the plane and wake up the next morning in the country I’m visiting. This helps me to not waste a day of my trip and keeps me from getting jet lag, because my body is immediately synchronized with the local time. Borja was immensely hospitable when I arrived, even picking me up at the airport and driving me to his apartment right off the Grand Via. He stayed at his girlfriend’s place for the week, so I had full use of his place during my visit.

As we drove to Borja’s apartment from the airport, he turned to me and said that the area through which we were then driving was where Antonio López García lived. The next time I was in Madrid he said we would meet him, then he laughed and said, “We would track him down, that we will do it, that you will meet him one day.” I just smiled. Being in Spain at that moment was overwhelming enough for me; I just said “Yeah!”

I had no real mission for this short five-day trip, just wanted to have fun, catch up with Borja, get to know the city, see some amazing artwork, and track down some books on Antonio López García. I guess that’s a lot. Oh, and one of the guidebooks recommended Oreja de Cerdo tapas—roasted pig ears. (But after taking one bite, I don’t recommend it.)

Borja’s apartment was close to everything, in the heart of the city and walking distance to the major museums including Prado, Reina Sofia, Thyssen-Bornemisza Museum, and Sorollo’s house, as well as being close to the Plaza Del Sol and Mayor.

On the second day of my trip, Borja and I visited the Cuesta de Moyano, a street that has about two dozen open-air used book dealer stalls. It is very near Retiro Park and the Atocha train station. We scoured each bookstall in search of hard-to-find books on Antonio López García. Back home in Brooklyn, López García books are rare. We came away with a few treasures including one of the first publications of his work from the 70s and a small blue book that he had written called En Torno a Mi trabajo como pintor (About My Work as a Painter).

We were also able to buy some Cuban cigars for my buddies back home. Spain subsidizes the Cuban market, so the Spanish get the cigars for the same price as in Cuba. I’ve since made it a tradition to visit the same tobacco shop near Plaza Mayer on each of my visits to Madrid, even though I don’t smoke cigars anymore.

The next day we visited the Antonio López García Room at the Reina Sofia Museum, an amazing contemporary museum that is across the street from the Prado. Picasso’s “Guernica” is on view there, and in real life it is truly majestic.

I got up early on the second-to-last day of my trip so that I could draw at the Prado. I quickly got lost in all of the Ribera paintings. I love how he creates volume, and I’ve been trying to incorporate my study of him into the work I’m trying to create. His style is close to how I approach painting form.

After a full day of sketching, I received a call from Borja, asking if I could meet up with him. He said that a friend of his—an art rep and collector—had seen my work and asked to meet me. Borja had said that his friend was also one of Antonio’s collectors and that she had a few of his pieces. Unfortunately, the woman had limited availability that week, and could only meet that day. Borja said that he would arrive in a half hour to pick me up in front of the museum.

After drawing all day, I was a sweaty gross mess, and I asked Borja if we could swing by the apartment so that I could clean up and put on a button-down shirt. I wanted to look at least a little bit presentable. Borja said it was more important to be on time, rather than well dressed, and that we were already running a little late—there just wasn’t time. When I came out of the museum Borja and Jorge were already there. I jumped into the backseat and we were off!

We drove to the outskirts of the city to a more residential area of town that looked familiar to me, although I couldn’t quite figure out why. I was still a little out of sorts, having been overwhelmed by my first full day of drawing at the Prado, and bowled over by so many inspiring works of art. I was also increasingly curious about this art rep-collector that I was to meet shortly.

As we drove down one of the main streets, Borja turned back to me. “Remember,” he said, “when I picked you up from the airport and I said that we were close to Antonio’s neighborhood? Well, right there is his street.” I replied, “Could we please just drive by his house quickly, so I could at least say that I had been there?” “Maybe on the way home,” he said.

About two minutes later we made a left-hand turn onto a quiet residential street. We parked and got out. The homes on the street were all gated with high walls. The “doorbell” was a box sort of contraption that had a call button and a keypad.

Borja walked up and buzzed, and the box came alive with a crackle and the voice from the other end that spoke in rapid-fire Spanish. I only caught “hola.” The look on Borja’s face was a little distraught and confused as he responded. Were we too late? After a few minutes of quick incomprehensible conversation the door buzzed open.

The wall protected a little front yard with a humble two-story home in the middle. I had strange feeling walking through the doorway, a real sense of déjà vu. Had I been here before? On the front steps was an older woman in a simple grey house dress. Again I couldn’t help feeling I had seen her before. Was this the art collector’s maid? Was she the woman I was there to meet with?

The front yard garden was full of an assortment of fruit trees and plants, and among the foliage was a number of small marble baby heads. They were obviously Antonio López García’s work. I had only seen the colossal version of the baby head during his exhibition at the Museum of Fine Arts in Boston a few years before. Borja had mentioned that this woman was a collector of Garcia’s work, so I thought nothing of it.

We walked up the front steps and followed the woman inside. We stopped in the living room and on the mantle was another López Garcia sculpture, a portrait bust. The walls were covered with some amazing landscape painting studies that looked like they were the seeds of some much larger ideas. Borja was once again in an intense conversation with the woman in the humble grey dress.

I was really confused at this moment, partially exhausted from the full day of drawing, and my brain was tired of trying to follow the context of every Spanish language conversation of the last few days. I took Spanish in high school, so I would pick up every fourth or fifth word, just enough to kind of understand what was going on, but at this time in my trip, my brain surrendered and just shut down. I was in a fog of confusion, feeling like I had been there before and wondering if this was the art collector we were there to meet, or if we had missed the appointment.

I vividly remember the worried look on Borja’s face and how it suddenly changed as he nodded his head up and down in understanding. Borja just turned to me with a big smile on his face and proclaimed “We did it, you are here!” “I’m where?” I replied. “You are in Antonio’s home!”

For a split second I was in complete disbelief. Then it was as if my fog of confusion just completely dissipated and the world came into sharp focus, everything made sense. The woman in the humble grey dress was clearly Antonio’s wife. I had seen her in paintings, and the portrait bust and sculptures in the garden were also familiar to me. I had been here before, through Antonio’s work. Also the source of Borja’s worry was revealed, “But Antonio isn’t here, he is at the studio. We will go there, now.”

The studio was only a short walk from the house. We walked out to the car and grabbed my backpack, camera and video camera. Borja had grabbed the books that we had bought a few days prior, and brought them along when Jorge and he had picked me up at the museum, so we could get Antonio to sign them.

We headed up the street towards Antonio’s studio. As Jorge, Borja and myself walked giddily up the slight incline, I could make out the vague outline of a man waiting for us in the middle of the street. Antonio was wearing a white smock decorated with plaster and paint smears. Under the smock were a t-shirt and shorts. We introduced ourselves and he introduced himself as if we didn’t know who he was. He ushered us into a nearby building where his studio was on the ground floor.

The studio was lit by skylight, and looked as if it had been an apartment in a previous life. The natural light was beautiful. There was a model stand in the middle of the room and what had looked like little landscape painting projects and sculpture projects scattered around the room. We followed him into the naturally lit kitchen of the studio. He gave us chairs and we settled down to hang out with one of the most respected representational painters alive.

The walls of Antonio’s studio were a hodgepodge of newspaper clippings, intricately gridded-out drawing studies, torn-out images from art books or magazines of Greek statutes and modern paintings, a compositional study of a painting that he was working on in the royal palace, a portrait of the royal family of Spain, and some images of his own work that he was laying out for a book project. Like a kitten in a room full of balls of yarn, these were just a few of the interesting things that were attracting my attention.

Antonio doesn’t speak any English and I don’t speak much of Spanish, and the only phrase I remember from high school was to ask if I could use the bathroom. I used it to get out of class to wander the halls. I’m guessing that Antonio did the same thing while in his high school English classes. I was extremely fortunate to have Borja and Jorge there to translate. It was also helpful that they are both extremely talented artists and had questions of their own.

Antonio was also very gracious and allowed me to film the entire visit. Again, fortunately, I had my video camera in my backpack with a fully charged battery and plenty of memory storage so that I could capture and translate the entire two-hour conversation.

About a third of the way into our time there, one of Antonio’s friends stopped by the studio, a young guy in his 30s, named Eduardo. He has known Antonio for 20 years. He grew up in the neighborhood, and also spoke very good English, having lived in America for a little while working for a few international tech companies. We all got along right away and the more translators in the room the better. Unfortunately, I know that I probably only really understood half the conversation that happened that day.

Antonio was very earnest and steadfast in his opinions, in some ways stubborn. One discussion was with Jorge, who had started a painting of a mechanical box in the underground that inspired him. Because the space between the box and the tracks was only about three feet, he decided to work from a photograph of the box in his studio, rather than compete with all of the people getting on and off the trains while he painted.

López García was really against this idea; he said that if the subject could not be painted from life then the subject was out of the realization of the artist and shouldn’t be painted. Both arguments were passionately debated, as you would no doubt expect in Spain. My own opinion falls somewhere in the middle. I now use photographs to paint from all of the time. When I was in school, on the other hand, I used to paint only from life, but I ultimately found this style limiting in subject matter and scale—not to mention it was wicked expensive. I strive now for a hybrid approach. I paint as much as I can from the live subject, and I’m always looking to the photo reference as if it were a living person, so there is a lot of editing that goes on beyond the photo.

What I was struck with the most on this visit was Antonio’s courage. He doesn’t care about selling a painting or about the market, or how difficult a painting is to paint or what anyone else thinks about his subject matter. He is just concerned with the work itself and the meditative process of creating the piece. He said that he knows that there are paintings that he will never finish. Some of his paintings have taken him over a decade to “finish.”

In a review of Antonio’s 2008 Exhibition at the Museum of Fine Arts in Boston John Yau stated this so elegantly: “For López García,” he said, “being truthful to what he sees amounts to embracing what he knows to be true: time is devastating and unquenchable, and it devours us all.”

López García really is the living embodiment of Howard Roark. He views himself as just a humble painter, painting and sculpting his life as honestly as he possibly can, regardless of the onslaught of time. A quote whose source I don’t remember sums it up for me: “The brushstroke lasts longer than the hand that created it.” This is a truth I always think about when I have a deadline for an exhibition and I feel like I’m rushing a painting.

In the long run—in the big picture of what I want to create and what I want my work to represent—is this show’s deadline important enough for me not to take another week or even a month on the painting to get it better and closer to what is in my mind’s eye? With Antonio, he is thinking not in weeks or months, but sometimes in years. To make this painting better—closer to his vision—that may be what it takes.

It is for these reasons that Antonio and his work represent the artist that I wish to be, the path that I want to follow. Not that I would swap my work for his or want to copy him in any way. His art is his journey and mine is my own open-ended search for understanding. He represents the values that I hold near and dear to my heart: authenticity, time, depth, weight, and purity—values that seem to be the first ones compromised while trying to make a living as an artist.

While I was sitting in the little kitchen of Antonio’s studio, I was struck with a question that had always been in the back of my mind. It was more of a curiosity really, regarding one of his paintings. The painting was part of the Boston Museum of Fine Arts exhibition of Antonio’s work I had attended in 2008. This exhibition was hugely influential to American representational artists, including myself, and I can already see its impact on many of my fellow artists.

I made the trip to the exhibition towards the end of its run. Here in Chinatown, New York, you can hop an old Greyhound bus up to Chinatown in Boston for only 15 bucks each way, so one morning I got up early and jumped on one of the earliest buses headed north to Boston to see the show. There really is something about seeing paintings in person rather than just printed or digital reproductions. It is kind of obvious, but in reproductions you really do lose the richness, texture, subtlety, depth and scale of the real thing. As long as I have the means to do so, I hope to ultimately see all of my favorite paintings in person. The travel and expense are well worth the experience that the real painting has to offer.

This exhibition in Boston had the feel of a holy site in Jerusalem. But to be honest, I’m only guessing at that since I have never been to a holy site in Jerusalem. The rooms of the exhibition that were on the ground floor of the museum had a solemn, reverent air to them. When I got there I ran into a few other artists from New York that I hadn’t seen in some years, who had also made the four-hour trek north to see the exhibition.

What also blew my mind was that I ran into my friend Emil Robinson, who had come to the show from Cincinnati, Ohio along with Jonathan Queen, a ridiculously talented still life painter. We had all made this pilgrimage to see the show. Emil is an amazing artist I met while we were both studying at the Art Students League a few years ago. This was crazy to me—way before the Facebook days. Only five or six years ago the world of painting was way less connected. Today everybody knows what everyone is up to and what shows are happening all over the world. It is an amazingly collaborative and supportive environment on Facebook. Seeing all of these artists at this show was also comforting. It is great to know that you are not the only crazy person when it comes to the painting life.

Okay, so back to the mystery question that I had for Antonio. While I was at the Boston exhibition, which I soaked up like a sponge, or at least tried to, there was a painting called “The Table.” The painting is of his family sitting down to share a dinner. The figures flicker in this liminal space as if in motion, and right in the foreground on the dinner table amongst the painted remnants of food is a photo of a piece of meat glued to the canvas.

This baffled Emil, Jonathan, and me. This was something that I had never noticed in the reproductions of the painting. I had just assumed that it was a painted part of the canvas. Why did he do that? This was my main curiosity about his work. Today, the art world seems to be getting more and more convoluted. So I braced myself for some complex explanation about why he added this collage element to the painting.

The answer surprised me. He said that he was working on the painting for a while in the studio and was never quite sure of the composition of the elements on the table, so instead of painting the meat, he decided to just add a photo of it, to move it around and see if the composition worked. He left the painting to work on some other projects and the gallery had sold it as it was, with photo attached. So he decided that it would stay that way.

Overall we spent a little over two hours with Antonio discussing different artists, the different representational art cultures from country to country, as well as his main influences. I left with a huge thirst to paint and draw more, and was truly inspired about the directions in which I wanted my own work to go. I wanted to make my work as personal as I could get, without the input and influence of a market that dictates what is more saleable or popular. Something stirred inside of me, stimulated me to journey towards a more authentic and heartfelt body of work, one that is unbiased and gutsy!

The weight of how valuable Antonio’s time was didn’t strike me until we were driving home. I felt so and how fortunate I was to have had this experience and the immeasurable friendship of Borja, who worked hard to track down Antonio to make this experience possible. It truly was the surprise of my life.

Fast forward to a year and a half later, I got an email from Eduardo. He was coming to New York with his wife and was wondering if he could stop by the studio. I told him of course and we had a great visit together while he was in town. I’m so glad that he made the trek out of Manhattan to my Brooklyn studio, especially while he was on vacation.

One night about a year later, I thought of how amazing it would be to do a life-size painting of Antonio. It couldn’t hurt to explore the idea, right? What is the worse that could happen? Only that he could say “No.” So I sent out an email to Eduardo asking if he thought the idea had any possibility of happening. The first email I sent him was in January of 2011, to which I never received a response. For some reason in April 2012 the idea was rekindled in my head. I thought that it had been over a year since I first asked, and that I wouldn’t be a pain if I asked again. This time I received a response in a few weeks, and learned that the original request was sent to an email that Eduardo didn’t check often. He replied that he had no problem checking with Antonio to see if it was something that he would be interested in doing.

At this time, Antonio was extremely busy, with museum exhibitions and meetings all over Spain. He had recently had a solo exhibition at the Thyssen-Bornemisza Museum and his time was in high demand; he was travelling all over Spain, lecturing and planning further exhibitions. So it was a challenge for Eduardo to even communicate with him.

After a few months, I got another email from Eduardo. He had talked to Antonio, who said that he would love to pose. Now the only difficult part was figuring out when this could happen. He had been extremely busy, and I had been travelling a little more lately as well. We finally settled on the month of November 2012. I left the entire month open so I could travel there as soon as I got word from Eduardo that there was a window of time in which Antonio would be back in Madrid. At the beginning of the month we settled on a ten-day stretch over Thanksgiving. I bought my airline ticket and two weeks later I was off to Spain.

So this brings me back to where this story started—fumbling through my painting as one of my painting idols and role models is remarking on the funny shape of my ear. What goes through your head when you have someone posing for you for whom you have such tremendous respect for? For me it was incredibly humbling, even though I was pretty confident in the finished study.

I’ve learned to embrace my insecurities over the years, so I’m ok if the painting doesn’t turn out well. In a strange way there isn’t a thought in my head that is negative. Maybe this is a false confidence, a coping mechanism for the brain. I figured that anything that is put down on the painting is part of this pivotal experience for me. There is no thought of what anyone else thinks of the painting, even the model, in this case Antonio. This is probably the most valuable lesson that I have learned from these experiences getting to know Antonio, his work and career.

It’s about having this purity of observation and a positive meditative approach to painting that comes solely from artist him/herself. The experience and time that we put into our paintings add a psychological depth to the work. These works are the cumulative collection of our thoughts about what we are painting, mistakes and successes mingling together revealing the history of how the work was observed. This is how the artist puts his viewers into the space of his works.

I didn’t want this to be an instructive piece, but in a holistic way I think in a way it is. It is about developing a state of mind, about being your own artist, about being who you are and bringing your own truths to your work, in the way that only you can. Individually, we are the sum of our own life experiences and investigations as humans. These experiences cling to us like our unique fingerprints. Harvest these truths with what, why and how you create. Have the courage to write your own personal “novel” without words.

In truth this story is more about life than it is about art. It is about developing lifelong friendships and understanding through example about the type of artist and person that I would like to grow and evolve into. I learned to strive to be more like Borja and Eduardo, just as much as I learned to be fearless like Antonio.

In 2006 Borja took the chance on emailing me about meeting up, and I followed Borja’s example in contacting Eduardo six years later, which led to the incredible experience of clumsily recording my own unfocused fractured thoughts while painting Antonio in his studio.

Toward the end of that painting session in Madrid, as I was wrapping up my brushes and gathering up my supplies, I looked up at Antonio. With a thoughtful expression he spoke to me in Spanish. I had the usual puzzled look on my face when Borja turned to me and translated: “Antonio says that you have guts for coming all the way to Spain to paint him.”

I just muttered, “Thanks, I’m learning.”

Thank you Borja, Eduardo, Jorge, and Antonio for being role models; I really appreciate our friendship.

Learn more about David Kassan at: www.davidkassan.com

Visit EricRhoads.com (Publisher of Realism Today) to learn about opportunities for artists and art collectors, including: Art Retreats – International Art Trips – Art Conventions – Art Workshops (in person and online, including Realism Live) – And More!

What a wonderful story about two exceptional artists. It should serve as an inspiration to all that understands what is written. Yes, a hardy thank you.

Comments are closed.