Learn how this group is using revolutionary technology to turn toxic acid mine drainage into richly colored, non-toxic paint pigment for artists.

From Toxic Drainage to Paint Pigment

BY JOHN SABRAW

Our team of artists and scientists is turning toxic acid mine drainage (AMD) (What is Acid Mine Drainage?) into non-toxic paint pigment, and in just a few weeks we will finish constructing a pilot plant to prove our process can work on an industrial scale, and also serve as an immersive, educational installation.

A few years after moving to Athens, Ohio I took a field trip with an environmental education group called the Kanawha project to some streams that were a strange orange color. I learned that this pollution is caused by Acid Mine Drainage and it kills nearly all the life in these streams.

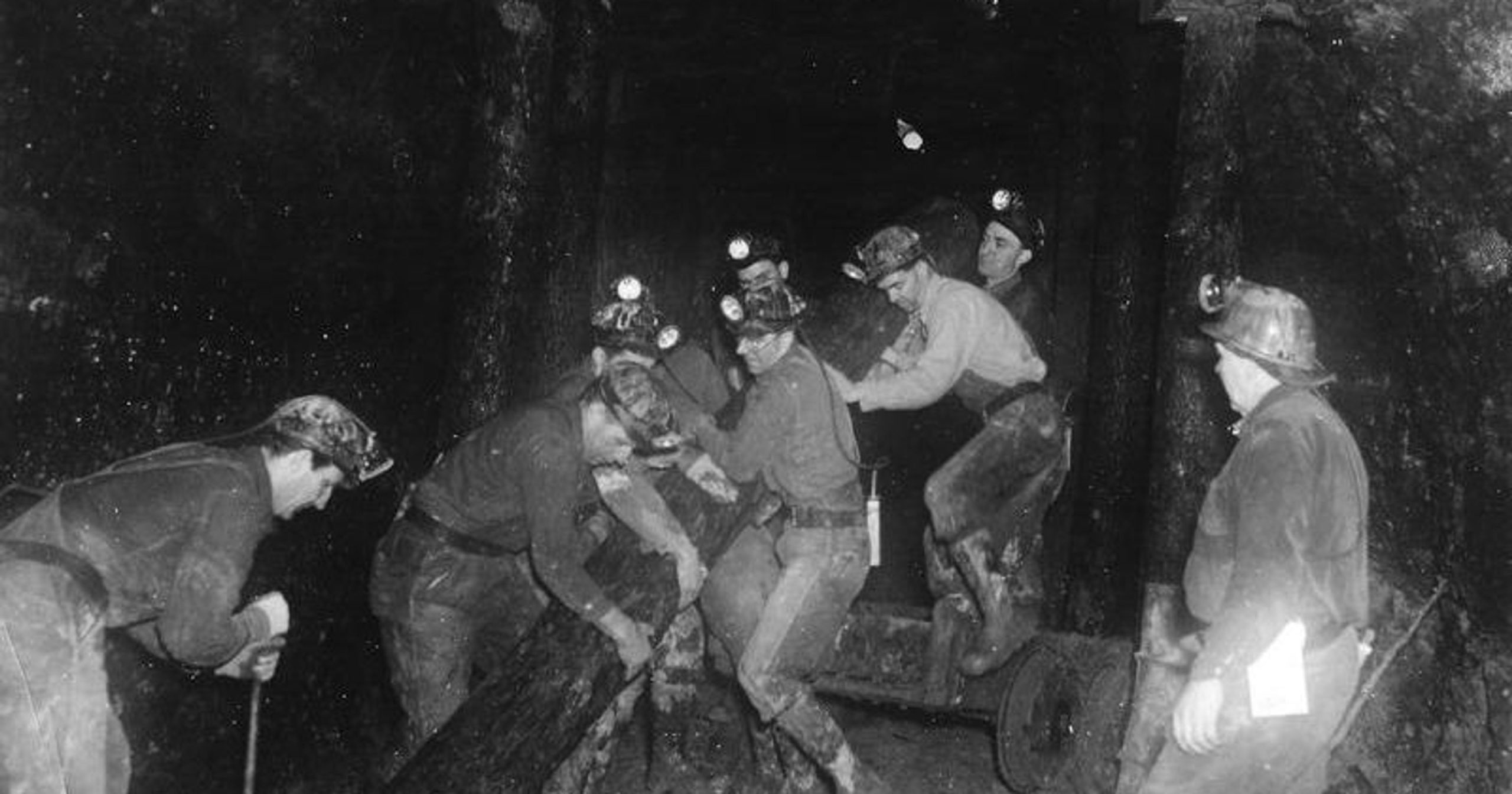

In Southeastern Ohio throughout the first half of the 20th century, strip mining and room-and-pillar mining were common. Forests were clear cut, soils scraped away, and tunnels dug to remove the coal.

A few active coal mines continue in the region, but by the 1970s most of the mining companies had moved on leaving behind open mines and disturbed land, with inadequate restoration. Much of the forest has now regrown, although it is young, but the underground mines continue to release toxic water to streams.

When abandoned, many of the mines fill with water, and the oxygen and water react with mineral surfaces that have been buried for 300 million years. When sulfides are present, these are common in Appalachian coal deposits, very high concentrations of sulfuric acid and iron are produced.

For decades, these abandoned coal mines have been oozing AMD – polluting 1,300 miles of waterways in Ohio (http://epa.ohio.gov/dsw/nps/index.aspx) alone. Some of the seeps we work with release over one million gallons of polluted water a day. This water can have a final pH below 2 and carry over 2000 lbs. of iron. It’s like junking two cars in the stream every single day. This high concentration of acid and heavy metals not only annihilates aquatic life, but can contaminate drinking water and corrode infrastructure like bridges; it’s both an ecological and economic concern.

Guy Riefler, a professor of civil engineering at Ohio University, came up with the idea of adapting a method of removing these toxins and then returning the clean water to the streams. He asked me to collaborate with him to transform the toxins into safe, colorful, sustainable paint pigments. We have been perfecting the pigment in our lab since 2010 along with watershed expert Michelle Shively.

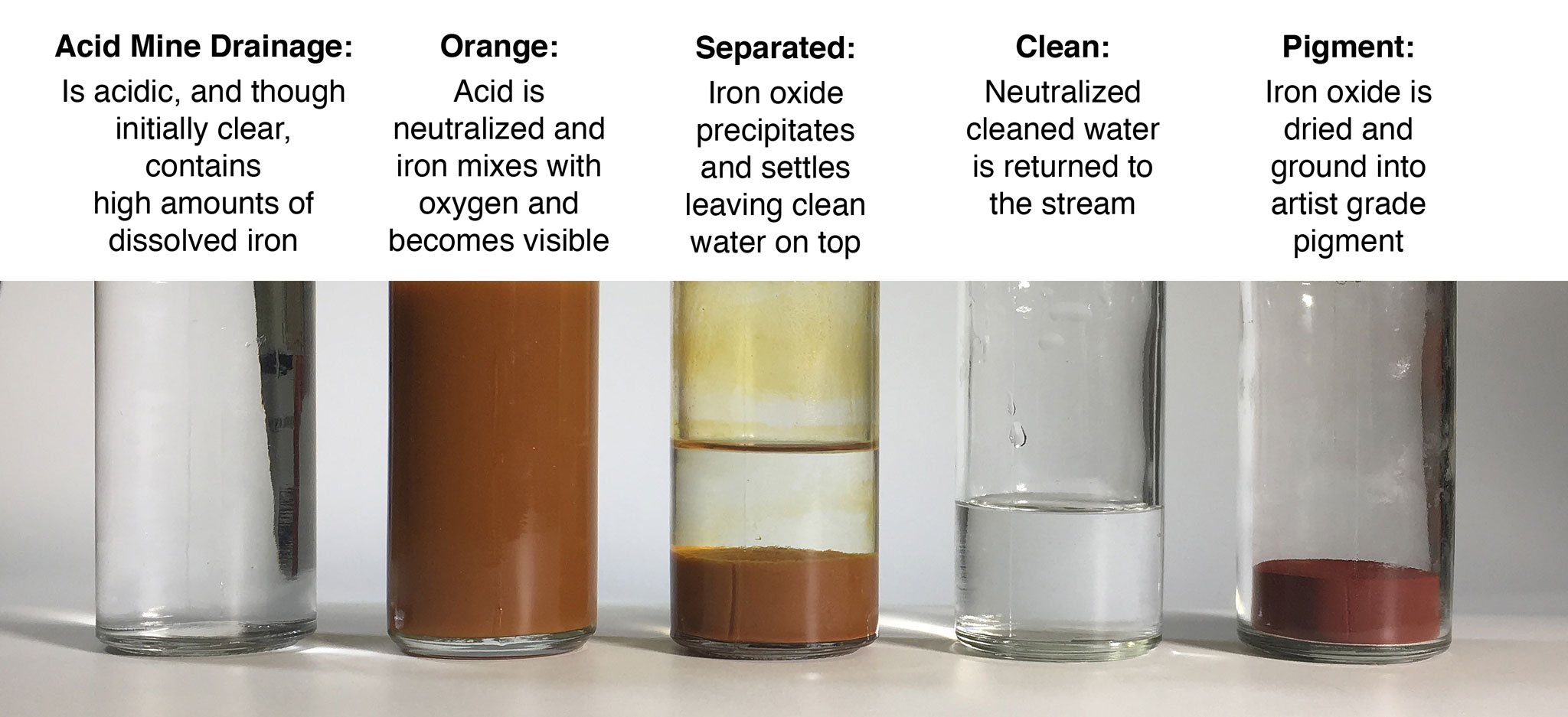

How do we turn the iron oxide into pigment while simultaneously cleaning up the polluted streams? First we intercept the toxic acid mine drainage before it gets to the stream, then we neutralize the acidity, extract the iron oxide, and finally release the clean, safe water back into the stream. The extracted iron oxide can now be ground into pigment and blended with different binders to make almost any kind of paint. In creating a viable product from contamination, our process provides a closed loop. We hope to make it possible to restore the streams with funds generated from their own clean-up and even provide local jobs.

What makes a good pigment? Hue, lightfastness, stability, grind, transparency, feel. That was my charge and I worked with Guy to achieve these qualities, but I also knew that our project needed an expressive visual demonstration that told the pigments story. So I began to use the pigment in a mix of other standard artist colors in my own paintings to build a contemplative dynamic relating to the sublimity of nature, but also the fragility of our current relationship with it.

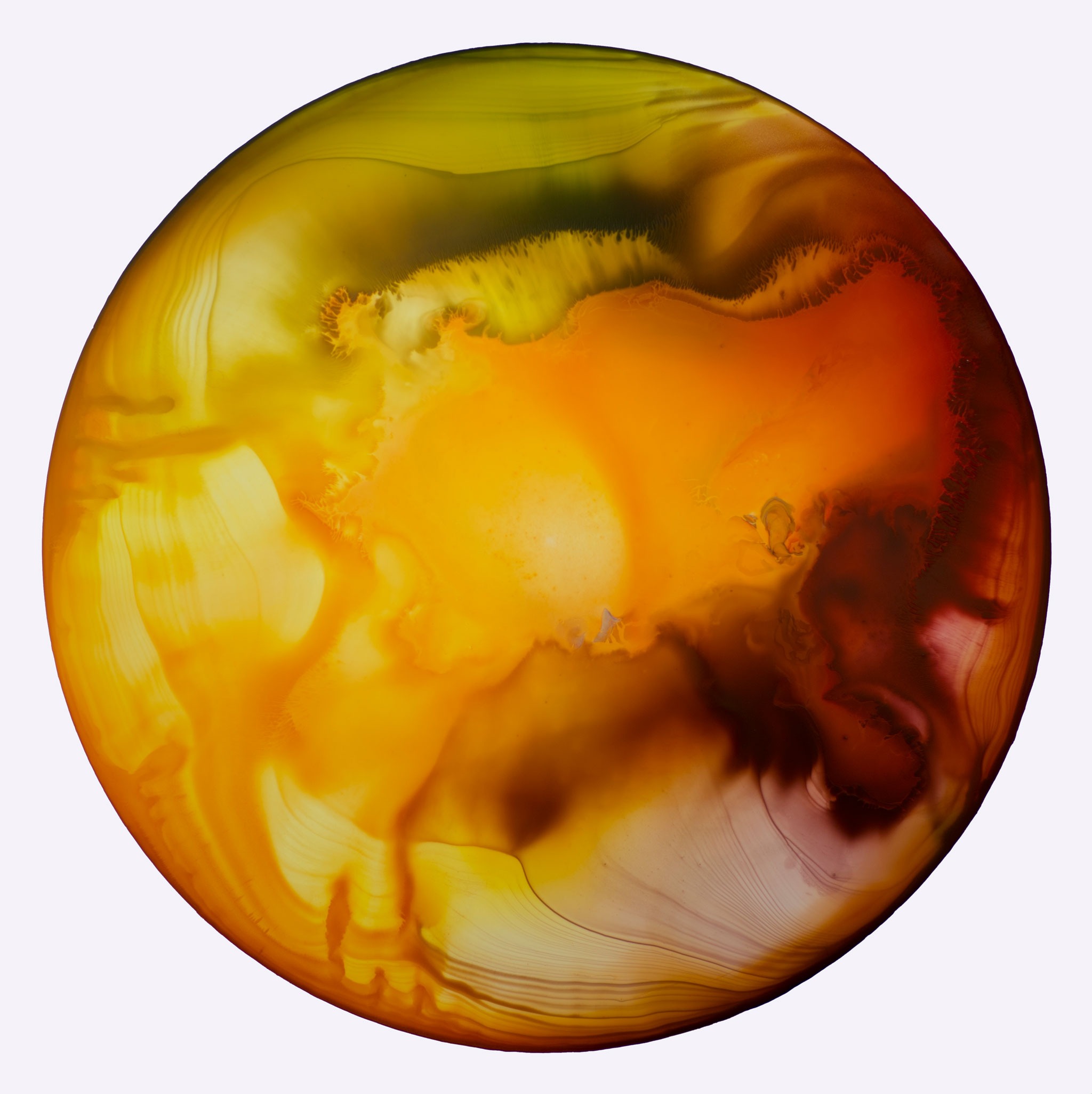

The paintings changed as the pigment changed, we worked to get the pigment from this color:

Perhaps best described in scatological terms, to something more desirable – like this color:

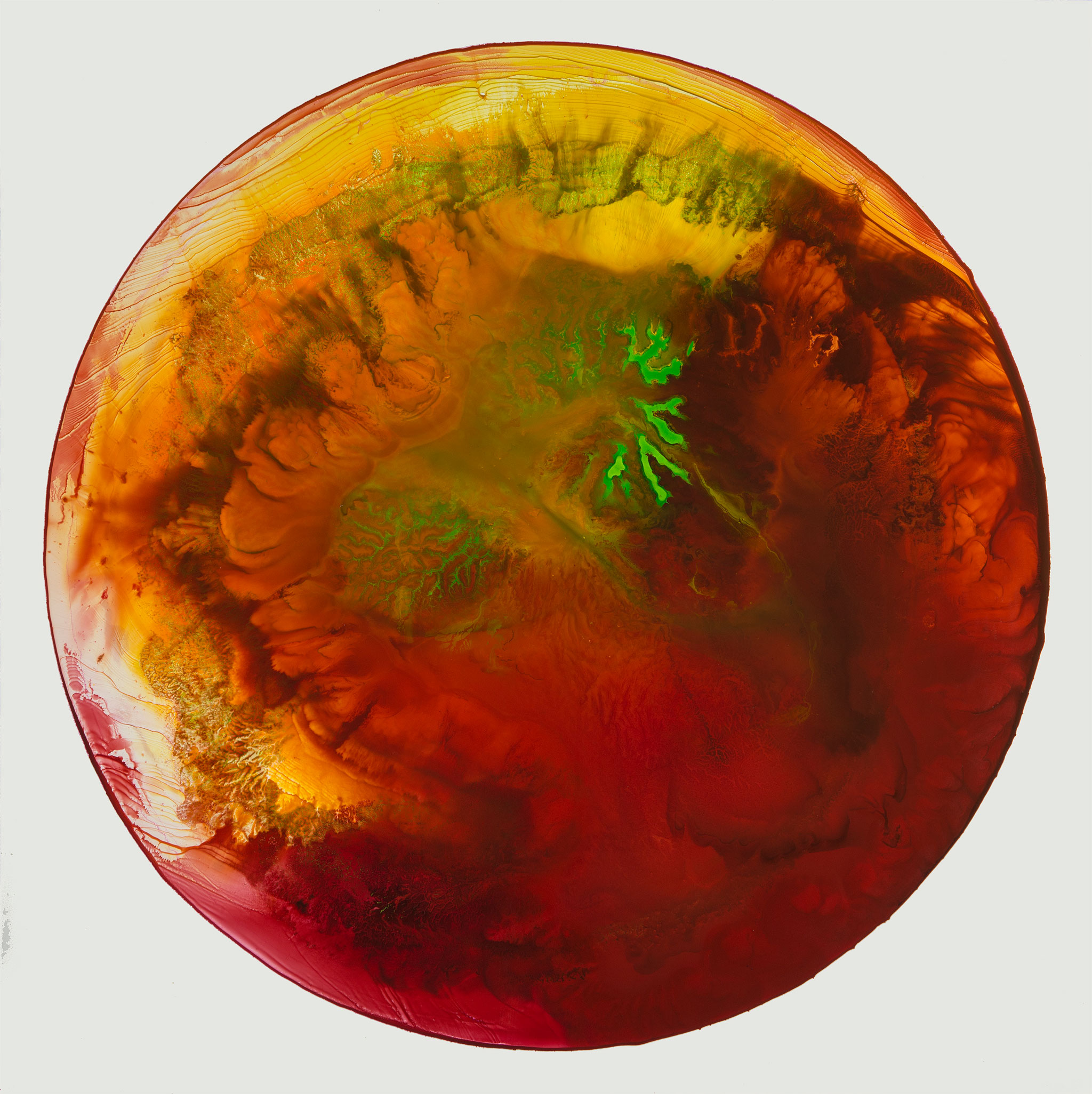

Far sexier and so my paintings reflected that, like this one:

We are finding ways of getting changes in the pigment colors by firing them at high temperatures for short periods of time. Here is what they look like made into oil paints: raw processed, after being fired at low temps, and being fired at high temps.

I have a deep and long-standing reverence for metaphysical and pragmatic contexts regarding our place within the universe. I am driven by the big questions: Why are we here? How did we get here? Are we doing the right things while we are here? Where do we go from here and where do we end up? Simple yet penultimate things to contemplate; particularly in juxtaposition with the quotidian. Phenomena that at first glance appear prosaic often reveal upon closer examination both order and chaos co-existing in complex relationships that create a unique sense of the sublime, with endless permutations possible between the macro and the micro.

My current work focuses on natural phenomena, the earth’s ecosystem as a whole, and our role within that. In this simultaneously romantic yet clinical experimental examination of science, environment, and the painting process, I use chemical interactions and probability to reveal a surprising aesthetic. Painstaking painting methods are coaxed into interacting and amalgamating over durations of up to several months. The result are complex, luminous, mysterious paintings that strike a balance between controlled and organic processes.

I believe an artist’s role is to create catalytic experiences that in turn foster examination of the key events of our time. This examination in turn may result in actionable realizations. What artists work on is compelling a strong enough response from viewers to encourage thought and dialogue. To do so the artist creates psychological and emotional impacts, not merely factual or informational, instead – experiential.

Recently I was asked how our AMD project has influenced me as an artist and human on planet Earth. After investing in this project for so long, I have come to the realization that even the smallest, most obscure attempt at engaging in environmental, community, or humanitarian work or conversation can have a positive impact, and I cannot know ahead of time how small or large that impact will be. So I remind myself to just do something. Don’t worry if it’s going to fix everything or not, or if you’ll be made fun of (hint: you likely will be).

Artists are spatially inventive; your crazy idea of how to clean up, prevent, or make new is probably pretty damn good. And even if it isn’t, it will spark someone else to tweak it and make it work. You are already your own best asset, don’t let the lack of a specialized degree or other training stop you from trying to make a positive impact. We need everyone.

Enter Gamblin

As a colorhouse that promises to be kind to artists and the environment, turning this pigment into paint was something Gamblin felt both compelled and honored to do.

In 2018 we officially joined forces by making one full batch of paint with the reclaimed pigment. The process to collect the pigment worked, and an oil paint manufacturer was on board. The concept was no longer just an idea, it was a reality.

Our team in Ohio needed funding to scale the project so we took the campaign to Kickstarter and used the tubes of paint as an incentive for patrons to back the project with a $100 pledge. When the campaign exceeded its goal of $30,000 the project was funded.

And the momentum didn’t stop there. Support and interest from artists poured in from around the world; people wanted the paint and we wanted to make it. But for Gamblin to bring these colors to market they needed pigment. Lots of it. Enough to make 2,500 three-tube sets, to start.

The Kickstarter funding was used to design and build a pilot plant with a goal to refine the process and a dream to build a full-scale facility that could treat 1,000,000 gallons/day. This got the attention of the Ohio Department of Natural Resources, who helped submit a proposal for a multi-million-dollar plant that would generate local jobs and produce over 5,000 lbs of pigment every day. The grant was made and in late 2019, Gamblin received a pallet of Reclaimed Earth Pigments. It was exactly what we needed to make the initial run of 2,500 sets.

Gamblin has volunteered countless (wo)man hours formulating, testing, naming, designing, and creating Gamblin Reclaimed Earth Colors: Rust Red, Iron Violet, and

Brown Ochre.

Gamblin is also giving 20% of set sales back to the cause and encouraging our retail partners to donate a portion of their proceeds as well. Purchasing this set not only benefits the project financially, but it literally and directly creates a demand for the pigment and a demand for clean rivers.

*The team has discovered that within just one year after cleanup, life returns to these once-barren waters.

THE LIMITED EDITION OIL PAINT COLORS: RUST RED, IRON VIOLET, BROWN OCHRE

RUST RED

In its transparency, it carries the warm color of rusty water. From the tube and in mixtures, Rust Red is exactly what you’d expect: an earthy red-orange.

IRON VIOLET

Meet the first mauve color Gamblin has ever made. Straight from the tube, it’s a deep, earthy violet with a unique texture. Add white and it becomes the violet you see in the clouds at sunset or dawn.

BROWN OCHRE

Naturally opaque and warm with a golden undertone. This pigment isn’t heated to the extent of the other colors, so it retains the deep yellow/brown hue of the raw iron oxide.

SUSTAINABLE PACKAGING

Gamblin is committed to reducing the use of plastic and unnecessary packaging wherever we can. We designed this set without plastic shrink-wrap. The sleeve and insert are recyclable, and the structure of the packaging has a function; it’s a primed panel made in Oregon by our friends at American Easel. It’s the ideal painting surface made with U.S.-grown poplar sides and a Baltic birch face.

AVAILABILITY | HOW TO BUY

The new, full-scale True Pigments treatment plant has the capacity to treat 1.4 million gallons of water and produce over 5,000 lbs of pigment every day. This facility will generate local jobs and it will eliminate the perpetual pollution source in Truetown, Ohio. Considering the sourcing and complexity of the project, Gamblin is introducing the Reclaimed Colors as a Limited Edition set. We feel passionate about our role as paint-makers and we hope to support the project until the troubled ecosystems are restored. However, our commitment to make these colors ultimately rests in the balance between supply and demand; painters will play a powerful role in the sustainability of this project. To purchase a set, please check with your local art supply retailer.

Share your work and see what artists are creating using #reclaimedcolor.

Related Article > Is Cadmium Paint Toxic?

I remember this mineral story. I thought the color was amazing.

I’m so glad someone is making paints from it. The pigments look wonderful.

(I’d call the scatological color “Loaded Diaper”. TMI?)

Comments are closed.