Matthew James Collins has been training successful artists for over 20 years. His teaching atelier in Florence, Italy offers a variety of study options. Workshops on painting portraits are offered throughout the year.

This article is sponsored by Realism Live: A Global Virtual Art Conference.

Register now and save.

Painting Portraits: Historical Approaches for Contemporary Practice

By Matthew James Collins

Art comes from art. The spark that ignites the passion in aspiring artists is often an experience with a work or works of art — at least that is what happened to me. Inspired by paintings in the Art Institute of Chicago during my childhood, I knew that I wanted to be an artist. My compulsion to draw, paint, and sculpt had a purpose. This transformative step began a multifaceted journey that involved internal growth through aesthetically engaging the external world. Admired masterworks became beacons, their authors the guides upon the quest. Art History, more than just a collection of dates and images catalogued in the past, metamorphosed into mythology. It recalled the hero journeys of those who came before. Beyond the anecdotes, select episodes offered a glimpse into the practice and technique of the language used to express their aesthetic vision.

During the 1990s there was a definite vacuum in figurative art education. No available formal structures offered the skills required to create the works that I admired. Technique was discouraged at university art programs. A lack of possibilities forced the creation of an alternative path. My interest in researching the techniques and practices of artists of the past began.

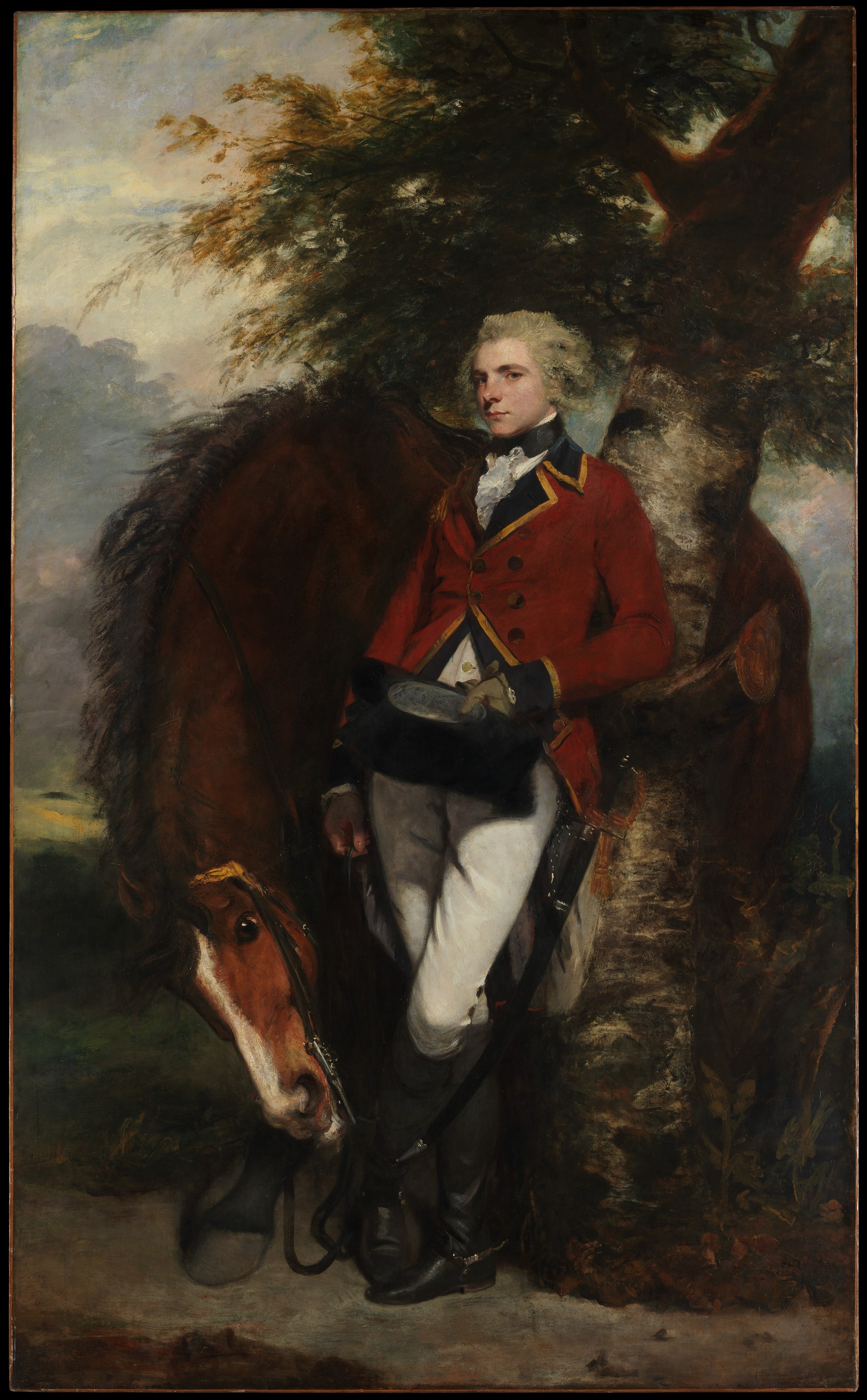

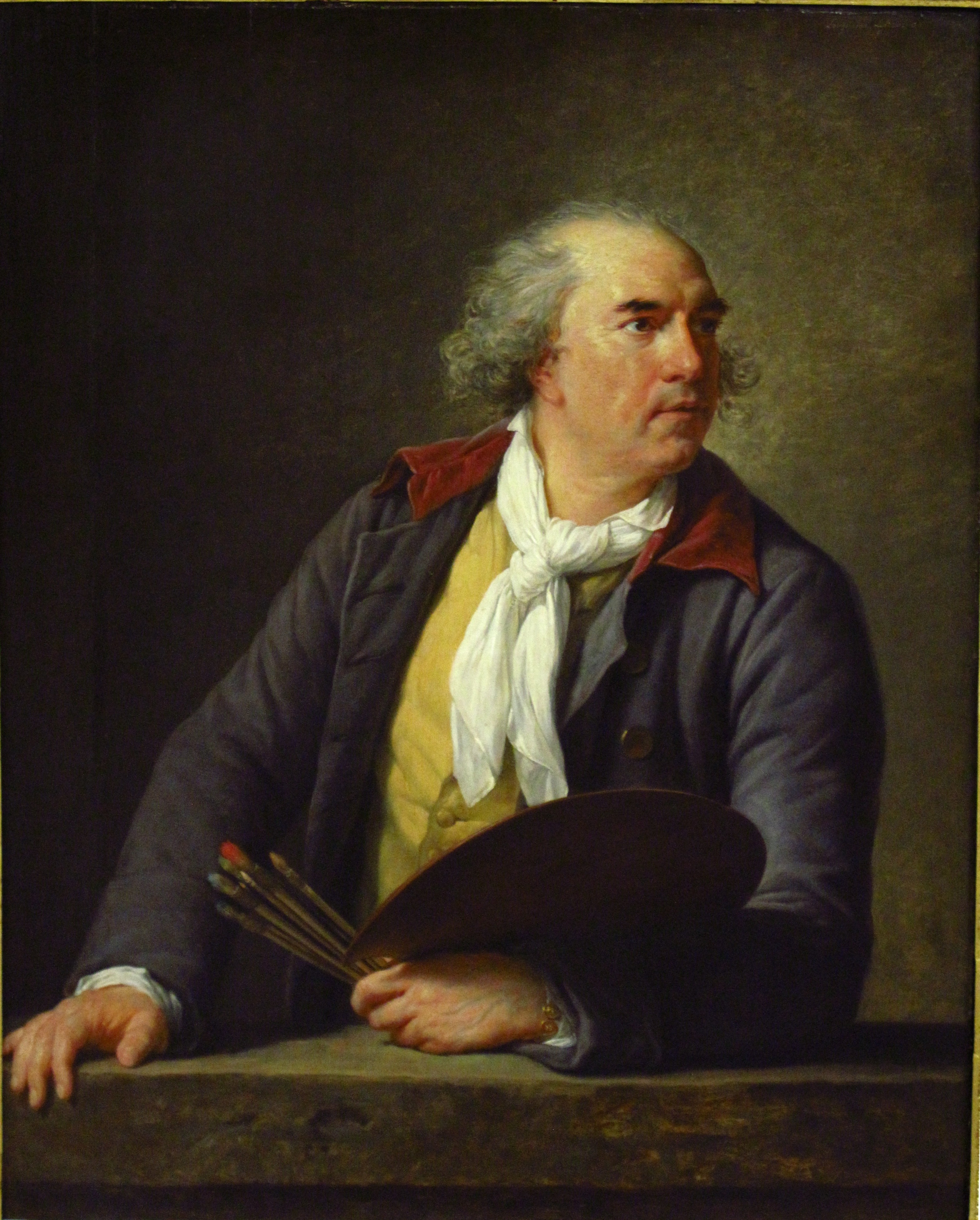

A definitive document on the formation of artists was created by the British school portrait painter, and founder of the Royal Academy of Arts, Joshua Reynolds. In his Discourses, a series of lectures delivered at the academy between 1769 and 1790, Reynolds outlines the scope of art and the proper course of its study. They were specifically directed to art students and examined the intertwined relationship between art, experience and craft. The study of art was a balance between following the wondrous examples of the past (the visual language) and gaining the requisite skills of drawing and painting what we see (observation skills). As important as the Old Masters were, he warned that to truly fulfill ourselves as artists we should study them but “instead of treading in their footsteps, endeavor only to keep the same road.” (Discourses. Second discourse, p. 71) Reynolds strongly felt that working directly from Nature was essential for creating work of significance. By doing so the individual voice of the artist is expressed.

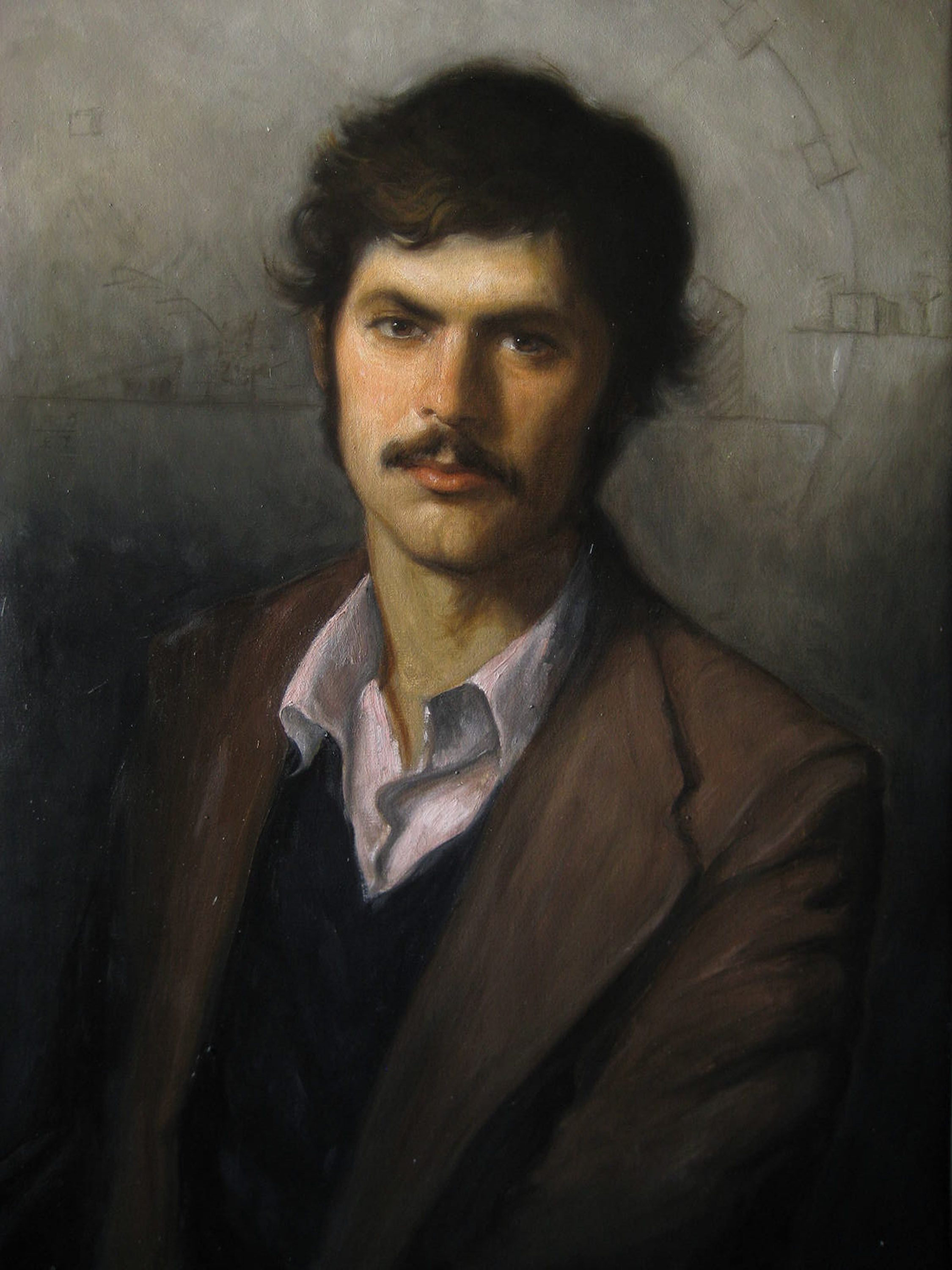

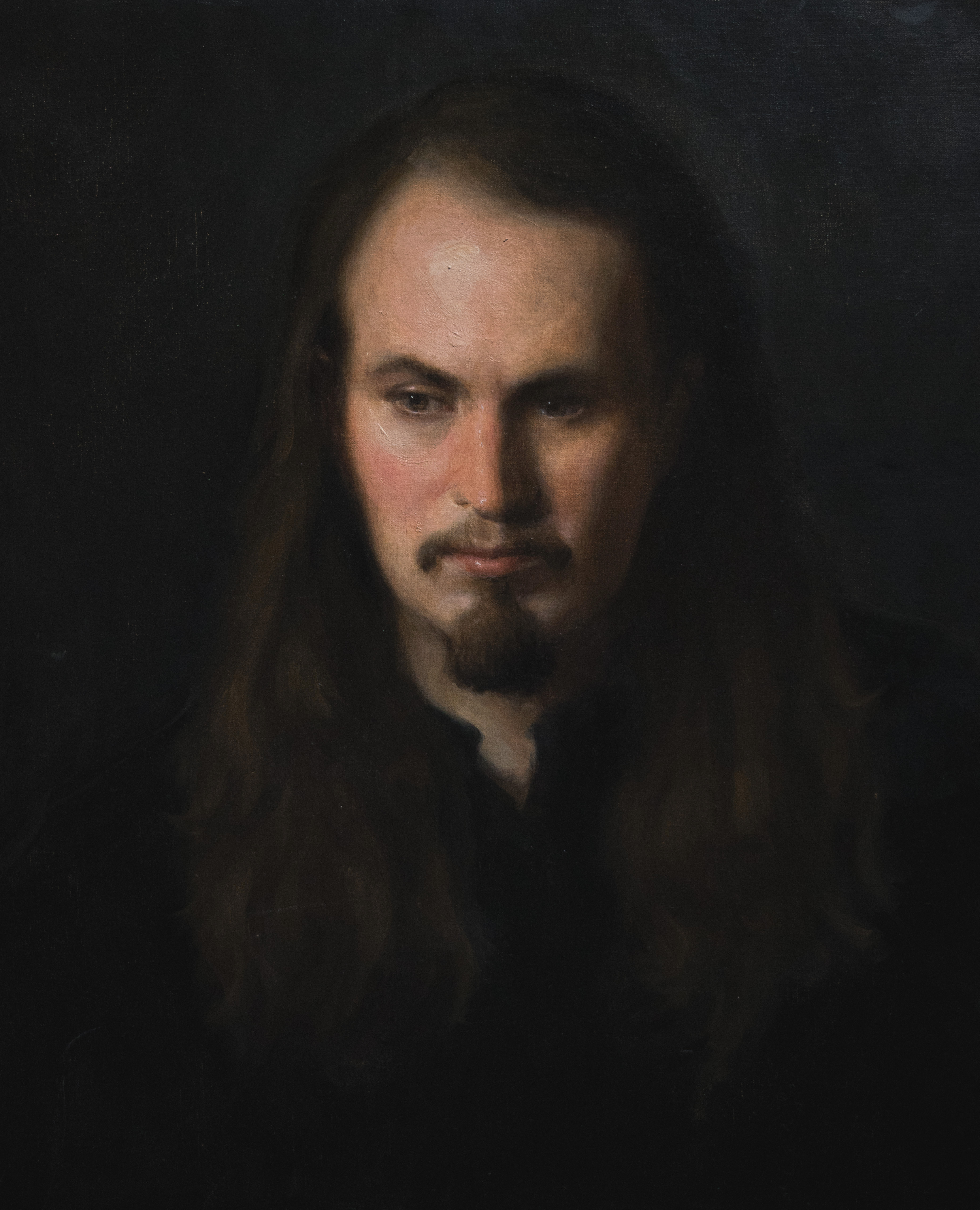

Taking Reynolds’ advice to heart, I developed my drawing, painting, and sculpture skills working directly from life as I read incessantly about the course of study of artists before me. The fruit of my research was put into practice, emulating the procedure of my heroes. Interestingly, the historical eras that garnered the majority of my attention, those that spanned from the late 16th century until the beginning of the 19th century, coincided with the rise and eventual supremacy of life-size portraiture. I paint and sculpt in a variety of genres, but the universal expressive power of the human face has always held a special attraction. The ability of portraiture to bridge time, space, and culture is impressive. The nuances of facial expressions are endless. With the life-size image, the invisible wall between art and life disappears. The most powerful paintings I experienced in the museums were the figurative works to the scale of life. A select few would include Titian, Moroni, VanDyck, Velaszquez, Reynolds, and Rembrandt. All of these masters commanded a psychological power in their head painting. Consequently, I would like to focus on the studio practice of life-size portraiture in oil paint in this article.

After years of studying first-person sources, manuscripts, and practicing as an artist myself, I discovered a thread connecting different eras of time. An underlying logic tied together the wide range of sources on historic artistic practices. They all tended toward the most practical and efficient process. The result, natural and organic, enables the artist to create the work while liberating the poetry that art requires. Specific terminology has changed over time. However, the philosophy, principles, and basic stages of painting life-size oil portraits directly from nature have remained relatively immutable with variety left justifiably to the imaginative power of the artist. In fact, many remnants of those core ideas survive in contemporary figurative art.

It is true that certain technological developments have changed how many artists conceive portrait painting: The photograph and artificial lighting, in particular. However very few reputable contemporary figurative artists would publicly renounce the primacy of painting portraits from life and the superiority of natural light. I believe that reacquainting ourselves as artists with successful methods, tools and techniques of the past can only open the creative possibilities of our own work. One has only to look to the precedent of the Old Masters (Sargent included) to see the full capacity of the imagination given form with simple means via a well-honed studio practice.

Related Article > Drawing Portraits and the Challenge of Sanguine Chalk

Studio practice

Many different elements come together in creating a portrait painting. A lot of attention and contemporary research has already been dedicated to the material aspect of oil painting: supports, colors, brushes, mediums, etc. However, a sound studio practice is also essential. It is a flexible construct that organizes all the components at hand to the maximum benefit. This involves the use of a valid visual method, studio space, lighting, placement of the model, and the fracture of the painting itself. When all these factors come together in the right proportion the artist is more fully able to pursue the expressive freedom that art offers and nature inspires.

The body of documents, manuscripts, and first-person sources is too vast to completely share within this context. I have taken the liberty to share a selection of the citations relevant to life-size portraiture (but equally applicable to all forms of painting). The goal is to give insights in time tested aspects of successful studio practice.

Proper Lighting

The majority of historical documents concur on the importance and organization of light on the model. It should be fall from above from a single light source. Direct sunlight should be avoided so a northernly exposure is preferred (for the Northern Hemisphere). A large window is preferable with a system of curtains to control the light. A single light source should illuminate the model.

Leonardo states that “The light for drawing from nature should come from the north, so that it is not subject to change… The height of the light should be fixed so that every body casts a shadow on the ground which is as long as it is high.” (45 degrees). “The painter who strives to imitate nature should have a source of light which he is able to raise or lower.” ( Leonardo on Painting, p. 214-16, Yale University press, New Haven and London, 1989.)

Sight Size, A Visual Approach, And The Primacy of Distance

The Sight Size method is a natural and logical development when applying the principles of perspective to the problems posed by the logistics of life-size portraiture. What is sight-size painting? Briefly explained, it is an observational practice where the model and work of art are visually the same scale from a primary viewing point at a certain minimum distance. This method works best when the image is life size and the canvas is placed alongside the model. The artist should be from 4-8 meters from both. All the visual information is taken from the primary viewing point (and secondary ones) and then the artist proceeds to the canvas and develops the work from memory without recourse to the model while painting. Progress is checked, errors recognized, and more information acquired as the artist regularly returns to the primary and tertiary viewing points.

The discussion of Sight Size and its use has become quite a polarizing subject among contemporary educators and artists. Like all tools, the application of this method varies greatly and can be utilized to benefit or be completely misunderstood. At its most powerful, Sight Size is comparative measurement to the scale of life. It has been adapted or even misapplied to a variety of purposes, mainly to under life-size work. Unfortunately, in the hands of certain practitioners it has devolved into a mere measuring tool of the piecemeal. The strength of sight size lies in its probable origins where it was applied to resolving the challenges posed by painting the life-size portrait.

Essentially distance is the most important factor. Only from a distance can the artist evaluate and develop relationships of shape, value, and color that are impossible to perceive up close in life scale work. It also simulates the ultimate goal of any large-scale painting; that is to communicate clearly over a great distance to the eventual viewer from a variety of viewing points.

The importance of viewing one’s work from a proper distance cannot be overemphasized and is essential for life-size images. The Early Renaissance artist, painter, and writer Leon Battista Alberti in his book, “On Painting,” states that the artist should try to “place(s) himself at a distance … from which point he understands the thing painted is best seen.” (Alberti, p.51) Leonardo Davinci also suggests, “It is also advisable to go some distance away, because then the work appears smaller, and more of it is taken in at a glance, and lack of harmony and proportion in the various parts and in the colours of the objects is more readily seen.” (DaVinci, p.263) More specifically for portraiture the 18th century portraitist Elisabeth Vigee-LeBrun states in her Advice on the Painting of Portraits: “You should be as far away from you model as possible; this is the only way to catch the true proportion of the features and their correct alignment.” (Vigee-LeBrun, p.354)

Placement Of Model

The model should be placed upon a pedestal as to roughly arrive about eye level or slightly higher to the artist. Observing the model “eye to eye,” sets the models eyes on the same level of those of the painter. This being the “horizon line” for the perspective system reduces distortion. Considering that the final placement of the most portrait paintings is higher than the average eye-level of the viewer, often painters would sit the model slightly higher than their eye level. Vigee-Brun emphasizes this by stating “You must sit your model down, but at a higher level than yourself.” (Vigee-LeBrun, p.354)

The Mirror, The True Master

The mirror has been a fundamental tool for visual artists since the Renaissance. By viewing one’s work in the mirror, mistakes and errors become more evident. Leonardo states that “You should take the mirror as your master” (Da Vinci, p.202; Leonardo on Painting Yale University press, New Haven and London, 1989)

Elisabeth Vigee-LeBrun suggests “You should also have a mirror positioned behind you so that you can see both the model and your painting at the same time … it is the best guide and will show up faults clearly.” (Vigee-LeBrun, p.355) Her advice recalls specifically the configuration of canvas and mirror in Velazquez’s enigmatic statement of the art of painting: Las Meninas.

The Big Shape And Proportions Over Detail

Establishing the larger relationships between heights and widths is the essence of the ‘Big Shape.’ Developing the general structure, proportion, and placements before introducing details is imperative to creating a successful life size portrait.

Credit line: (c) (c) Royal Academy of Arts / Photographer credit: John Hammond /

Joshua Reynolds in Discourse 11 states:

“The excellence of portrait-painting, and, we may add, even the likeness, the character, and countenance, as I have observed in another place, depend more upon the general effect produced by the painter than on the exact expression of the peculiarities, or minute discrimination of the parts. The chief attention of the artist is therefore employed in planting the features in their proper places, which so much contributes to giving the effect and true impression of the whole.” (Discourse 11, p.272)

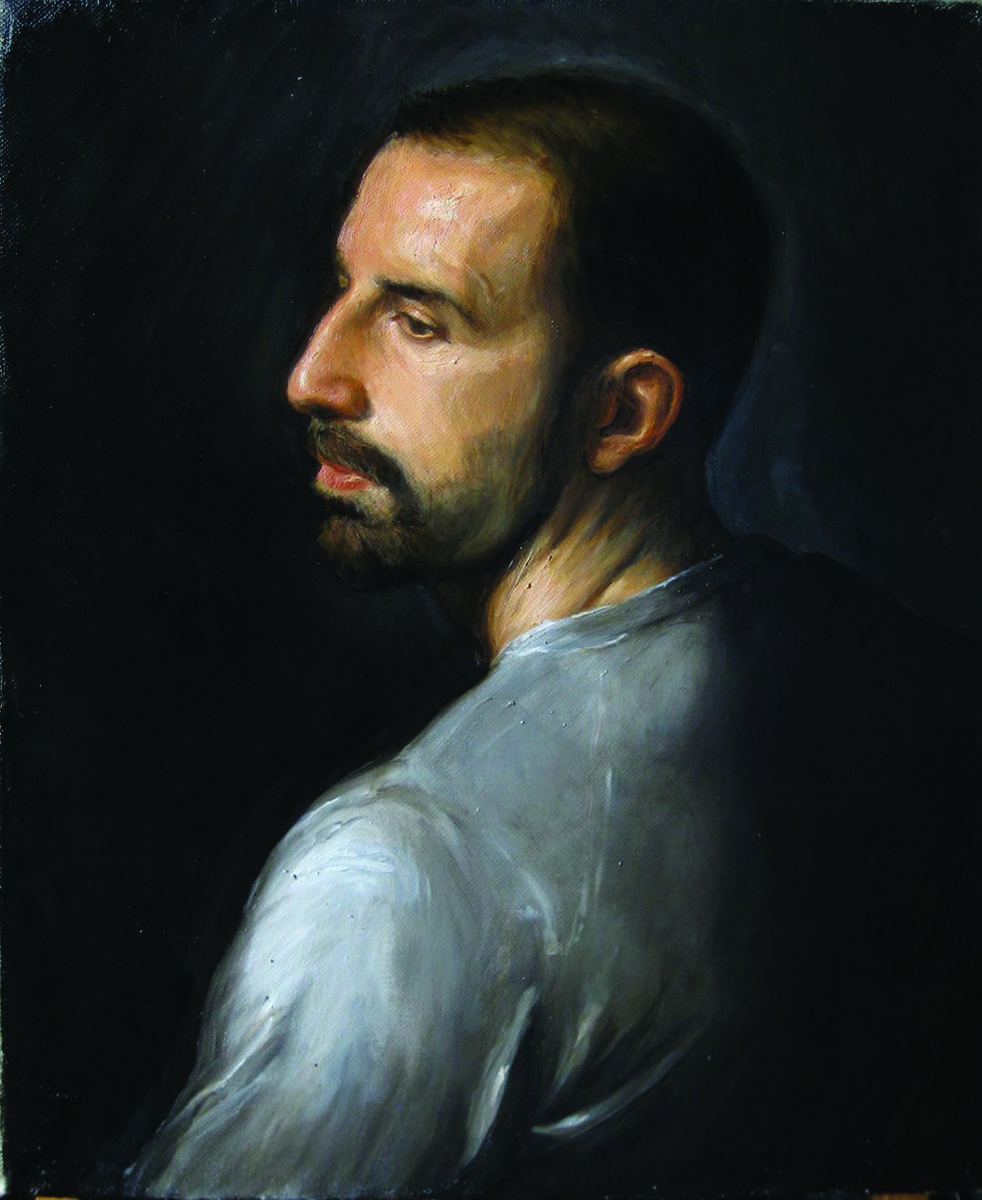

Developmental Stages Of The Portrait

Luckily recent scholarship has reevaluated the position of Anton Van Dyck (1599-1641) to give him the prominence and importance that he deserves. Much admired during his lifetime, Van Dyck was widely considered the best portrait painter of his generation and perhaps after. His technique and execution are flawless yet not sterile. A prodigy placed in the highly developed studio culture of 17th century Flanders, Van Dyck developed quickly. After being recognized an independent master in his teens, he went on to assist Peter Paul Rubens in his studio. Not much later he was encouraged by Rubens to travel to Italy and complete his formation by experiencing the glory of Italian art. Later Van Dyck was called to England to work for Charles I and his court. His influence on English art was enormous and he could justifiably be considered to the father of the British School.

An account concerning the artistic theory and procedure attributed to Van Dyck was recorded in the Common-place book of Dr. Thomas Marshall and dates from the 1640s, as stated by Mansfield Talley in his book Portrait Painting in England: Studies in the Technical Literature before 1700. The process was divided into four stages (or sittings): Sketch, Dead-colouring (la Maniera lavata), Modelling la (Maniera sbozzata), and Final touches (la Maniera finite). (Tally, p.150-51) The strong influence of Italian art is seen in the choice of terminology.

Sketch

At the very beginning the shapes are drawn in a linear fashion with charcoal. The goal is to solidly develop the composition while constructing the features and elements required by the painting. A certain accuracy is emphasized. Details are subordinate to establishing the proportions, placements, and likeness. Drawing is the foundation on which the rest of painting will be based. Ideally the forms would be accurate and there would be no need for changes.

La Maniera Lavata or Dead Coloring

Using thinned paint, the lights and shadows are introduced in color. The full value-range is underplayed while emphasis on general relationships is explored. With this new information minor errors in shapes and drawing are corrected. This stage was also referred to as the Dead Colouring in the British school.

La Maniera Sbozzata or Body Coloring

Using more substantial paint, the light and darks are simultaneously developed along with the modelling. Color is developed as well. The drawing is evolved through the modeling. The painting is brought pretty much to completion.

La Maniera Finita or Final touches

Subtlety of the modeling and delicacy of the half tones are pushed. The lightest lights and darkest darks are resolved. Edge treatment is modulated to reinforce an overall idea of impression and effect.

Although the precise underdrawing of the first stage was dropped by many later practitioners, the concise categorization of three stages of painting was regularly repeated after. An important concept that underlies the process is that shapes, values, and color are developed simultaneously over the whole head. Drawing and color are unified in application. They are developed in tandem directly upon the canvas. Details are added only at the end once all the important overall relationships are established. This ties in very well the previously discussed concept of the ‘Big Shape.’

Conclusion

The common theme that connects the above practices is that they work together to aid the artist’s ability to “See.” Tools that overcome the physiological limitations of human sight, they facilitate the research in proportion that underlies the beauty in art. Often mistaken for technique “Seeing” is actually its guide. An important aspect of “Seeing” is recognizing the organically integral relationships of proportion, shape, value and color perceived in nature. Combined with imagination, sensibility and technique, they are expressed as a work of art. The creation of a life size portrait directly from the model poses serious logistical challenges that requires highly developed observational skills. When observation fails to provide the proper information artists often refer to formulas, a lacking summary of the subtlety of nature. A proper studio practice not only allows the artist to successfully complete his/her objectives but achieve a deeper, more complex expression of a personal aesthetic vision.

The diffusion of the digital image via social media diminishes the rare qualities of the life size image. With that, the risk of the devaluating the necessary tools required for its successful completion become more imminent. Despite the wondrous power of the digital age to communicate to unimaginable multitudes, it cannot replace the intimate truths of admiring oil color becoming flesh in a face mirroring our measure without mechanical filter.

Bibliography:

Leon Battista Alberti, On Painting, Trans. John R. Spencer, Yale University Press, Revised Edition, 1966.

Leonardo Da Vinci, Leonardo on Painting Yale University Press, New Haven and London, 1989

Leonardo da Vinci, The Notebooks of Leonardo da Vinci, Vol II Edward MacCurdy, Jonathan Cape, London, 1945.

Sir Joshua Reynolds, Discourses, McClurg and Co., Chicago, 1891.

Mansfield Talley, Portrait Painting in England: Studies in the Technical Literature before 1700, Paul Mellon Centre for Studies in British Art, Biddles of Guildford, 1981

The Memoirs of Elisabeth Vigee-LeBrun, translated by Sian Evans, Camden Press Ltd., London, 1989.

About the Artist:

Matthew James Collins was born in Oak Park, Illinois, in 1970. Nurtured in an artistic family, his enthusiasm for art was encouraged from the earliest age. By his early teens, his study of drawing had already begun under the tutelage of his father, James Edward Collins, an award-winning architect.

For more than 20 years, Matthew has been living in Italy studying and researching the classical techniques painting and sculpture. He shares his acquired knowledge through his teaching atelier in Florence, Italy.

An artist of unusually wide breadth, his oil paintings, frescos, and sculptures reveal a rigorous study of the masterworks of the past and a deep observation of nature. Not limited to a single genre his oeuvre includes portraiture, landscape, decoration, and figurative subjects.

He exhibits internationally and his works represented in public and private collections throughout the United States and Europe.

Artist Links: Website | Instagram | Facebook

Visit EricRhoads.com (Publisher of Realism Today) to learn about opportunities for artists and art collectors, including: Art Retreats – International Art Trips – Art Conventions – Art Workshops (in person and online, including Realism Live) – And More!