On Painting Portraits > Most of us can polish a portrait, but is it honest? Does it tell the truth about the sitter? Can it stand alone?

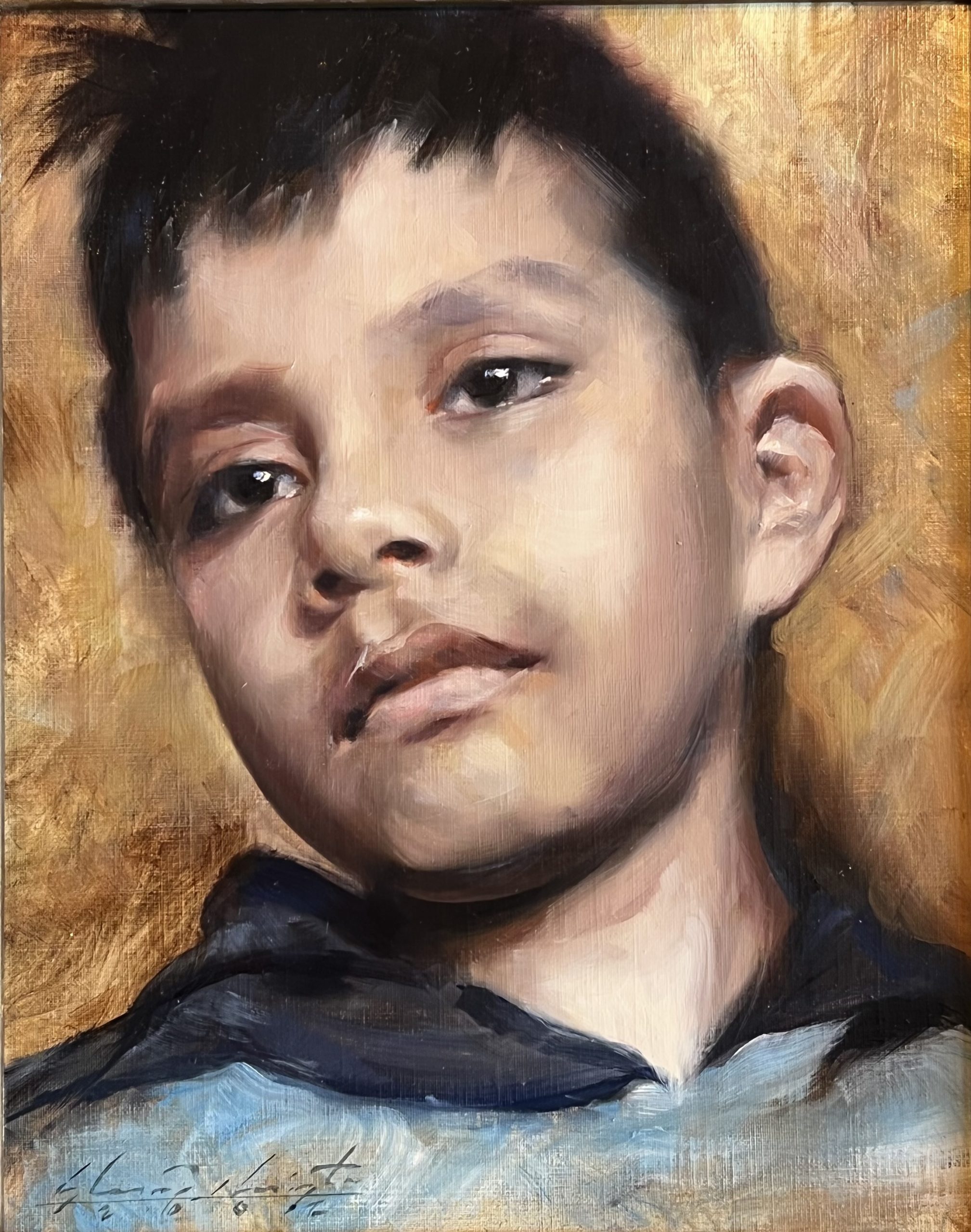

By Glenn Harrington

My friend David Leopold, archivist for both Al Hirschfeld and David Levine said:

“Hirschfeld and Levine were the masters of the ‘epigrammatic portrait’—simple, elegant, and sophisticated reduction to capture the essence of their subjects. They both were students of the human condition and brought that knowledge to each of their portraits. While the context of the finished work was different than other portrait artists, in that the work was made to be reproduced, they nevertheless took it as seriously as any other portraitist.

“Levine studied the masters and alluded to their work in his drawings. His gift was to be able to distill complex points of view into human traits, which he added to his portraits to make them compelling. Neither artist overdid the obvious, but rather accentuated their subject’s characteristics in a way that illuminates, rather than infuriates. They share this with artists such as El Greco and Picasso, artists who tinkered with realism in order to convey the true personality of their portrait subject.”

The Secret is Simple

Recently, while preparing to pose young sisters in their home, I joined them in selecting dresses from a variety of colors and patterns that complemented one another. Their interaction in performing the task hinted at their individual personalities. I asked the girls to seat themselves, readjusting them until the design of the painting started to take on form. I chose a location with single-sourced daylight, minimizing ambient light.

Simple, single-sourced light offers an optimum definition of form. Gilbert Stuart described it this way: “The whole theory of shadow may be taught by a billiard ball—the simplest object I can think of. Lay it on a table and draw it. You first sketch a circle; you then look at it, and there is one light, one shadow, and one transparent reflection; on the gradation of those all painting depends. My rule for a portrait is, one-third light, one-third dark, and one-third demi-tint.” Simple form comes first, but not to the exclusion of ambient light with its contrasting warm and cool colors, giving form variety and interest.

Painting has always been quasi-scientific in its efforts to capture reality. We understand the way in which form exists and develops, and we know that the interplay of warm and cool light and color exists, whether we always recognize it or not. When we begin to discover and understand these realities, we then have a basis on which to approach all our work. But it starts with our understanding of light and its effects.

Drawing

Early on in my career, after making preliminary sketches for a new painting, I found myself drawing out much of the final portrait in pencil on the linen, before I began painting. Initial sketches are still helpful in familiarizing me with the subject, but now I rarely spend more than a minute or two sketching on the linen. This is partly because I have become more confident in my drawing abilities, but more importantly, I’ve discovered that drawing with paint allows me to develop the overall mood of the figure, balancing features as the person begins to emerge in form and color.

I also found that the more committed I was to my detailed drawing, the less willing I was to cover it up. The process is more fluid when there is a healthy balance between structural drawing and emerging form. The resulting process is essentially controlled chaos.

Stuart said, “. . . in the commencement of all portraits, the first idea is an indistinct mass of light and shadows, or the character of the person as seen in the heel of the evening, in the grey of morning, or at a distance too great to discriminate features with exactness . . . Drawing the features distinctly and carefully with chalk is a loss of time. All studies ought to be made with brush in hand. It is nonsense to think of perfecting oneself in drawing before one begins to paint.”

Though we are all at different points of maturity in our approach, it’s interesting to consider Stuart’s perspective.

Color Control

Our studio palettes are one of the most diverse and intensely colored objects we know. It’s amazing how little color we need to create a colorful painting. I find myself designing colored object[s] into paintings rather than introducing color where it does not exist, toning down color, introducing grays, and establishing simple color themes.

When Stuart was asked if he had any particular mode or rule for mixing his colors he replied, “No, I mix them as I put sugar into my tea; according to my taste.” Sometimes in an attempt to create interest in overly quiet areas of a painting where texture and brushstrokes might dominate, I’ll break down the shadow into the colors that make up that neutral and apply them next to one another in a sort of Impressionistic way. I have also found that if I know that an area of a painting is going to be cool on the surface, it adds visual tension to lay a warm ground beneath it.

Surface

When visiting museums, most of my time is spent closely examining the surfaces of just a few select paintings. Books are a great source for investigating content and design, but they cannot truly reveal the depth and luminosity of a painting’s surface. Later, while recalling those inspected surfaces, familiar paths open up as similar effects emerge in my own work. The direction and design of brushstrokes are inspiring when seen live.

Evidence of drawing with paint in a picture is similar to the sculptor’s chisel—loaded brushes are intentionally applied; their variety of size and shape leaves the surface laden with interest. John Singer Sargent’s fluent paintings are just as interesting up close as they are at a distance. His brushstrokes remain on the surface as clear evidence of his remarkable thinking. About her father’s approach, Jane Stuart said in 1884, “The portrait demonstrates the artist’s proficiency in drawing with the brush to achieve a likeness with the most economical means.”

Every square inch of the painting matters in its part in building the whole picture—whether it’s the content or a design element. “If a story starts out with mention of a rifle on the wall,” Chekhov said, “it had better go off by the story’s end.”

Most of us can polish a portrait, but is it honest? Does it tell the truth about the sitter? Can it stand alone as a painting? Have we captured visual and emotional elements of our subject’s character that are true, denoting something unique about our time and their relationship to a greater, timeless audience?

Painters, like writers, are attempting to convey our perceptions of the realities confronting us. How we perceive each subject and situation makes us unique. It is to the degree that we are willing to involve ourselves intimately in the process that creates a painting with lasting value. Someone said, “No tears in the writer, no tears in the reader.”

Connect with Glenn Harrington at glennharringtonart.com and glennharrington.com.

Visit EricRhoads.com (Publisher of Realism Today) to learn about opportunities for artists and art collectors, including: Art Retreats – International Art Trips – Art Conventions – Art Workshops (in person and online, including Realism Live) – And More!

What is meant by “Most of us can polish a portrait,” ?

Comments are closed.