There is something odd in many of Bo Bartlett’s contemporary realism paintings, strange stories being illustrated even when it is unclear what they are.

Bo Bartlett: Still Keeping Us Guessing

By Daniel Grant

Perhaps you are familiar with the abstract paintings made by Betsy Eby, but you are almost certainly acquainted with what she looks like. A large percentage of the paintings created by her husband, James “Bo” Bartlett III (b. 1955), feature Betsy – clad, nude, looking this way or that, sitting, reclining, gazing off dreamily, or staring right at the viewer. It has now gotten to the point that, Bartlett admits, “when we walk down the street, people don’t know who I am, but they sure know who Betsy is. So, by default, they might know who I am.”

Bo Bartlett didn’t always put Betsy in every painting he created. The 65-year-old artist was portraying women during the 1980s and ’90s, before the two even met — they married in 2007 — yet many figures in those early works look just like her anyway. One picture from 1987, “Resurgere e Renasci,” a dream-like image of identical sleeping women floating up toward the sky, could be multiple portraits of Betsy but for the fact that they hadn’t been introduced yet.

Bartlett confides, “A longtime friend of mine, when he met Betsy, told me, ‘This is the person you’ve been painting your whole life.’ So, even though none of the women in ‘Resurgere e Renasci’ are Betsy, they all are. She was sort of my archetypal feminine, so for years I concocted and dreamed up figures that look like her. When I finally met Betsy, I was like, ‘Here you are.’”

Talk about having a type.

For her part, Betsy Eby (pronounced “EE-bee”) has adjusted to being a muse, and to dropping everything, including her clothes, when Bartlett needs her to pose. “I get a little pissed off when someone assumes I’m his bookkeeper or manager,” she says, but being recognized from paintings that do not actually depict her is just a harmless consequence of being married to an artist with such a strong sense of how his ideal woman looks.

Eby notes, “People will say to me, ‘My favorite painting Bo’s done of you was the one where…’ and they’ll describe a painting he made long before we met. I don’t correct the record; I just listen and nod. Because it’s not about me. I’ve learned that art is about projection. Viewers already have their own narratives, their own identities invested in certain paintings, and it’s not my place to interrupt that. This learned neutrality is a discipline, not a cop-out, and it requires a strong sense of self.”

A UNIQUE PATH

So, she is an artist’s muse, and he is Betsy’s husband. Now perhaps a bit more on him. Born in Columbus, Georgia, Bartlett took time off between high school and college to travel in Europe, including private art lessons in Florence with Benjamin F. Long IV (b. 1945). His teacher was a former U.S. Marine who had served two tours in Vietnam, the second commanding the Combat Army Team, and has since spent 45-plus years largely as an expat painter of classical realism.

While Long remained in Europe, Bartlett returned to the U.S., enrolling at Philadelphia’s University of the Arts before transferring to the Pennsylvania Academy of the Fine Arts nearby. He wasn’t in a rush to graduate, ultimately spending six years taking studio courses and never actually completing the liberal arts portion of his B.F.A. degree. His road to a career in fine art has not been straightforward, either. Bartlett made a living by painting portraits and earned a certificate in filmmaking at New York University in 1986, the same year his third son was born. (His first marriage extended from 1974 to 2004.)

Eventually, gallery exhibitions and sales entered the picture, first in Philadelphia, where Bartlett lived for 30 years (in 1986, Philadelphia Magazine dubbed him the “Best Artist in Philly”), and then in New York City. His timing was impeccable, as some of the most prominent painters of the 1980s were breaking away from abstraction to pursue figuration, usually with a critical or ironic sensibility. One sees similarities in style and intent among Bartlett’s work and Eric Fischl’s scenes of suburban decadence, Mark Tansey’s ironic commentaries on art history and art theory, John Currin’s takes on what society views as sexually provocative, and Robert Longo’s depictions of men and women in seemingly existential moments of great emotion.

Bartlett notes, “There are definitely parallels. There are paintings I was doing before I saw what they had done and vice versa. I think Currin [who is seven years younger than Bartlett] came along later, and so he would have been influenced by us; if he says or acknowledges that, I don’t know. But there was a group of us.”

Certainly, there is something odd in many Bartlett paintings, strange stories being illustrated even when it is unclear what they are. (With Fischl and Currin, one gets the point more quickly; Tansey’s visual puns are easy to make out, and the main question with Longo’s “Men in the Cities” series is whether the subjects are dancing or have just been shot.)

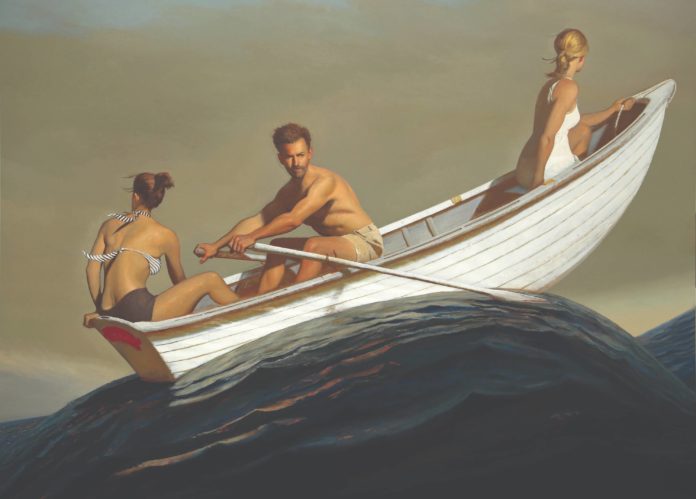

Bartlett’s “The Babysitter” (1999), with its teenage girl sitting on a disheveled sofa while buttoning her blouse, suggests improper sex. But what brought about the perils facing the twenty-somethings rowing on very choppy seas in “The Promised Land” (2015; shown at top)? Why is that woman (guess who?) lying on the grass before a wind-blown scarecrow, a tent, and a Ferris wheel in “The Cruel Fair” (2007)?

Bartlett’s New York City dealer, Miles McEnery, says his work is “haunting and familiar at the same time. You look at something that you recognize and then think, ‘Huh?’” Perhaps what distinguishes Bartlett from some of those other ’80s art stars is his interest in surrealism, not the semi-abstract or fantasy imagery of Joan Miró and Max Ernst, but more descriptive painters such as René Magritte and Salvador Dalí. Bartlett asks, “Doesn’t every teenager love the surrealists? By the time I was graduating from high school and going off to Europe, it was Magritte and de Chirico and Dalí who were probably my biggest influences.”

In Florence, Ben Long redirected Bartlett’s focus to the Renaissance and Baroque periods. As his education continued back in America, he became more influenced by such artists as Edward Hopper and Andrew Wyeth. “The End of Summer” (2006), with its favorite rock from the sea-shore resting on a window sill, shouts its inheritance from Wyeth’s farmhouse paintings.

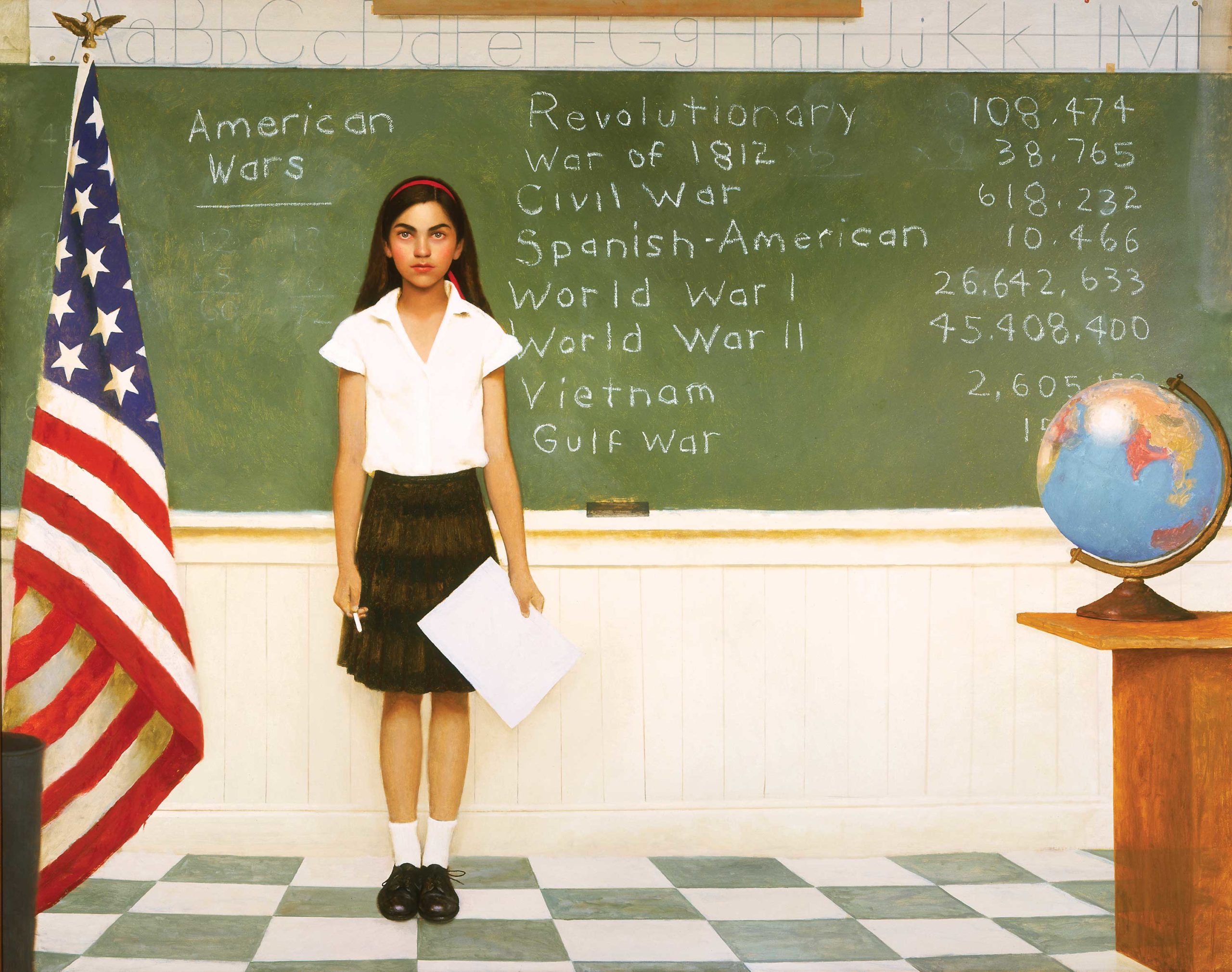

While Bartlett shares Hopper’s and Wyeth’s visions of loneliness and stillness, he has taken a more critical approach to Rockwell, creating images that resemble those of the great illustrator but with a more ironic vision. “History Lesson” (2002) features a young girl in a pleated skirt and white socks, bracketed by a globe and U.S. flag with a classroom blackboard in the background. She appears to be giving a class presentation on wars in which the U.S. has engaged; the blackboard lists the number of dead in each conflict, hardly a Rockwell sort of theme.

Bartlett describes some of his scenes as “Norman Rockwell turned on its head.” He goes on, “It’s definitely in that genre, but at the same time, it’s a starting point, taking it to the next level of psychology and awareness and all of the human struggles. I love that when you look at a Rockwell, you get it instantly. He’s a master storyteller for that exact reason. It’s very clear, and that’s not easy to do — in painting, film, or anything. But with my painting, I like the slow reveal, so that you see it and you acknowledge, ‘Oh, I recognize this. I know what’s going on here.’ Then you turn your head a little, and you start to say, ‘But wait, what exactly is going on here?’”

That is the mystery at the heart of numerous Bartlett paintings, a storyline at which we can only guess. “It’s not didactic in the sense that I’m presenting a concept,” the artist explains. “It’s grappling with a feeling and a mood about what it feels like to be alive now.”

Connect with the artist: bobartlett.com

- Visit PaintTube.tv to learn how to paint portraits and figures in the style of contemporary realism, and much more.

- Join us for the next annual Realism Live virtual art conference and study with the world’s best realism artists.

- Become a Realism Today Ambassador for the chance to see your work featured in our newsletter, on our social media, and on this site.