Contemporary Realism Art > Being able to impart your emotions into a painting is important in your work. Here’s why, and how to pull it off.

Visual Recognition

By Aaron Westerberg

Visual Recognition: (vĭzh’ū-əl rĕk’əg-nĭsh’ən)

How we interpret and ascribe meaning to the shapes and colors we see.

As painters we rely on Visual Recognition to tell our story. It is how we communicate. It is the basis of our language. The broader our visual vocabulary the better we will be at communicating in our own unique voice. I believe most of us only use a fraction of this tool when painting, thereby limiting our ability for self-expression.

Naturally, almost unconsciously, we recognize and interpret shapes, colors, and proportions. From just a silhouette, we are able to recognize a tree or a spoon. The specific details aren’t always necessary to understand what we are seeing. In staying true to the basic shapes of your subject, you are able impart your own interpretation or impression onto what you paint. The viewer is going to recognize the shape of a spoon in almost any way you paint it—bright color, dull color, happy strokes, labored strokes, etc. You don’t have to copy everything exactly as it stands before you for the viewer to understand and recognize what you are painting.

It’s amazing how much we use Visual Recognition in our everyday lives. At a distance we are able to recognize our friends and family at just a moment’s glance. In the same way we are easily able to recognize everyone in our high school yearbook even though the pictures of our classmates are only the size of a postage stamp. Most artists understand this, but don’t fully exploit the potential for emotional content or storytelling in their work.

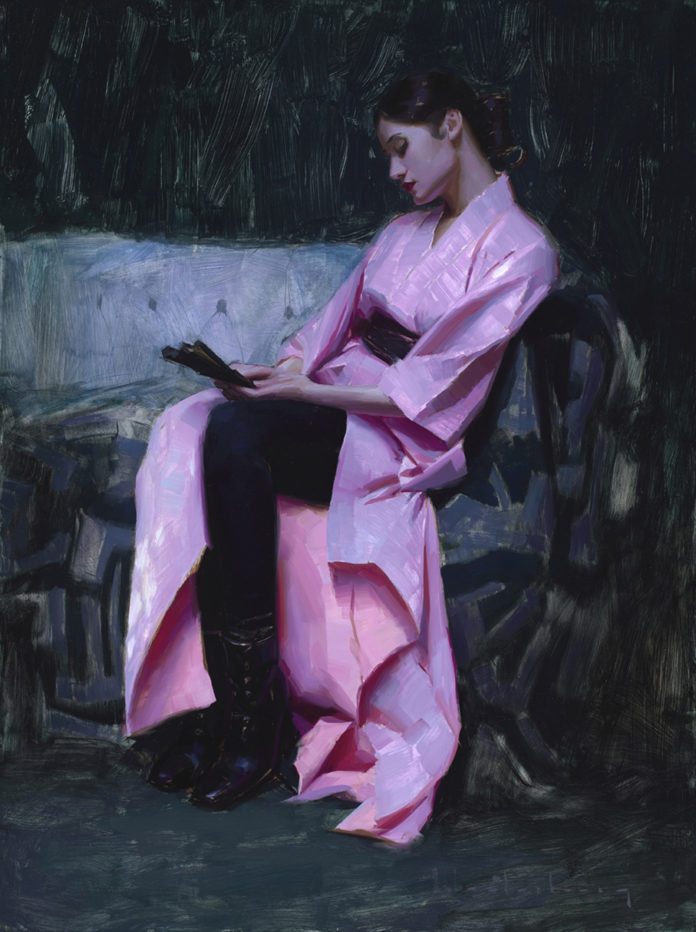

Aaron Westerberg, “Belena,” 16 x 12 inches, Oil on linen

Look at this painting I did of one of my students (Belena, above). Immediately you can identify it as a painting of a young woman based solely on the placement of the shapes. I used only one color and I hardly used more than two values. Yet you can recognize it as a painting of a young woman. It’s not the details that make someone look as they do; it is the proportion of their face, the distance between their eyes, the shape of their nose. It is all about the spatial relationships between the big shapes.

Relying purely on accurate shape placement gave me the latitude to change a few things and to add my impression of the subject. What did I change? I only used one color, I kept the value range high, (my darkest dark is only about a 5 value), and her hair really has no detail—it is barely more than a silhouette. The shapes alone are powerful enough to tell the viewer what I want them to know. You don’t have to be a slave to your reference; a few details are generally all that is needed to make your point. The viewer’s brain automatically fills in the detail, oftentimes better then we could have painted it. We want the viewer to participate in the painting.

Most of us know just from the shapes below that I painted two Boston Terriers, Stella and Lucy. Their ears give them away every time! Can you see how I added a different “emotional content” to each painting? They are similar in both subject and pose, but convey a much different mood and story.

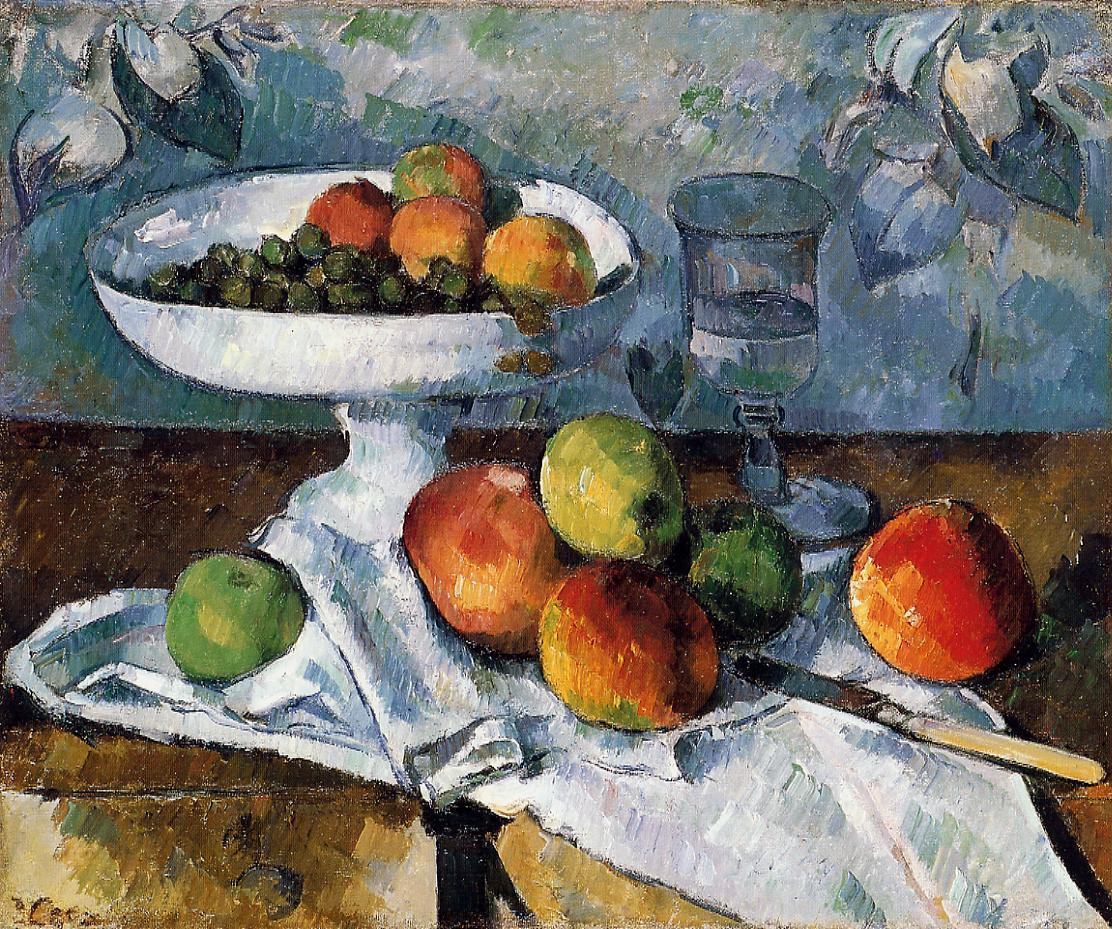

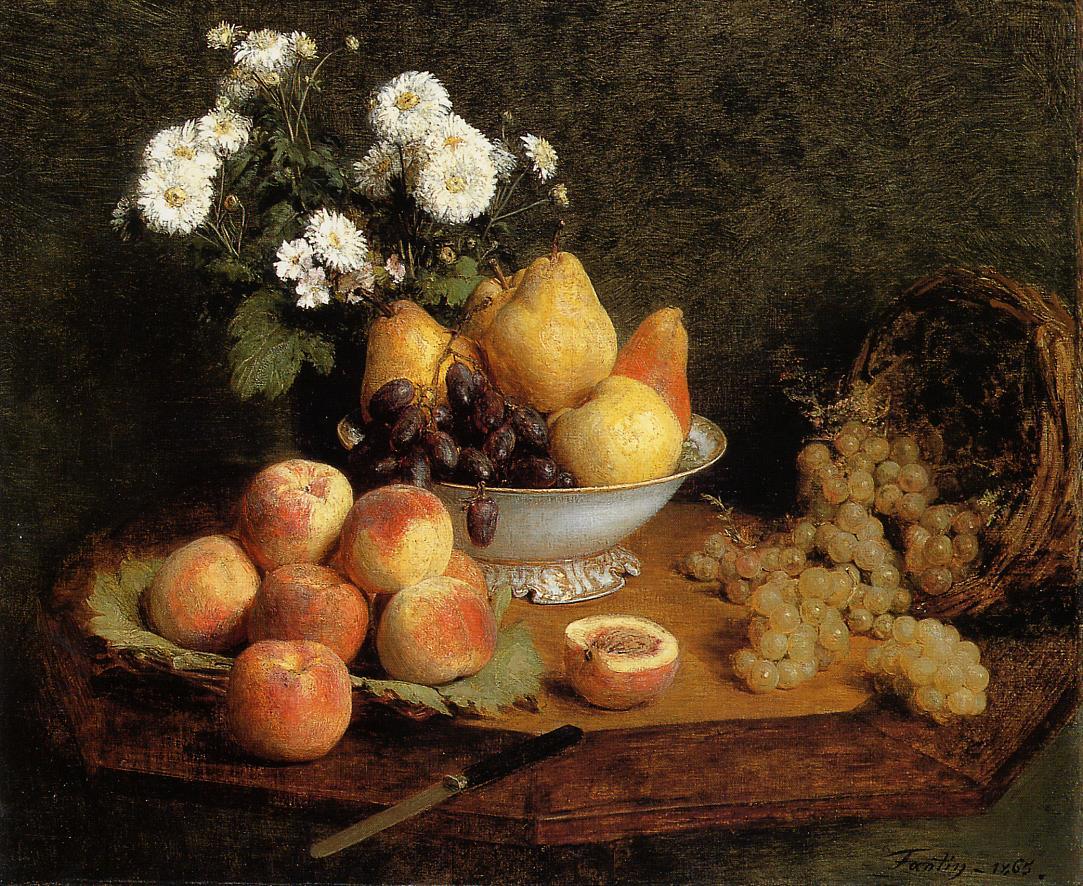

Next is another example of two similar subjects with two very different interpretations: Cezanne and Henri Fanton-Latour.

Just like anything, learning and consciously using visual recognition takes practice. The more complex the object the more difficult it’s going to be to simplify, so I suggest starting with simple shapes such as a piece of silverware or fruit. Paint the object you have chosen in four different ways. For example, paint one in a high-key, and one in a low-key; paint one in a hurried, rushed manner and one in a calm, relaxed manner—try to maximize their differences while at the same time being mindful to retain their intrinsic shape.

All this leads us to the underlying question: Why is being able to impart your emotions into a painting important in your work? Simply put, it will make your work more personal and unique. Your painting will be something no one else can do. You are communicating with the viewer about how you feel about your subject in a very clear and deliberate manner. You are free to paint whatever moves you; the emotion you are trying to convey will be actualized in how you paint, not only in what you paint. You are not just painting to accurately portray your subject; you are painting to portray that subject and how you are feeling at that moment in time.

Connect with Aaron Westerberg:

Website | Instagram

Visit EricRhoads.com (Publisher of Realism Today) to learn about opportunities for artists and art collectors, including: Art Retreats – International Art Trips – Art Conventions – Art Workshops (in person and online, including Realism Live) – And More!