Realism in Sculpture > Reflections on Sabin Howard’s “A Soldier’s Journey,” a World War I memorial monument. “A Soldier’s Journey” is a 65-foot-long bronze relief, which depicts not only soldiers, but also nurses, wives, and children.

From SabinHoward.com: On January 26, 2016, the World War 1 Memorial Commission announced the selection of the World War 1 Memorial Design Time and Concept. Architect Joe Weishaar and Sculptor Sabin Howard’s design THE WEIGHT OF SACRIFICE was chosen for the National World War 1 Memorial at Pershing Park in Washington D.C.

BY PROF. DONALD KUSPIT

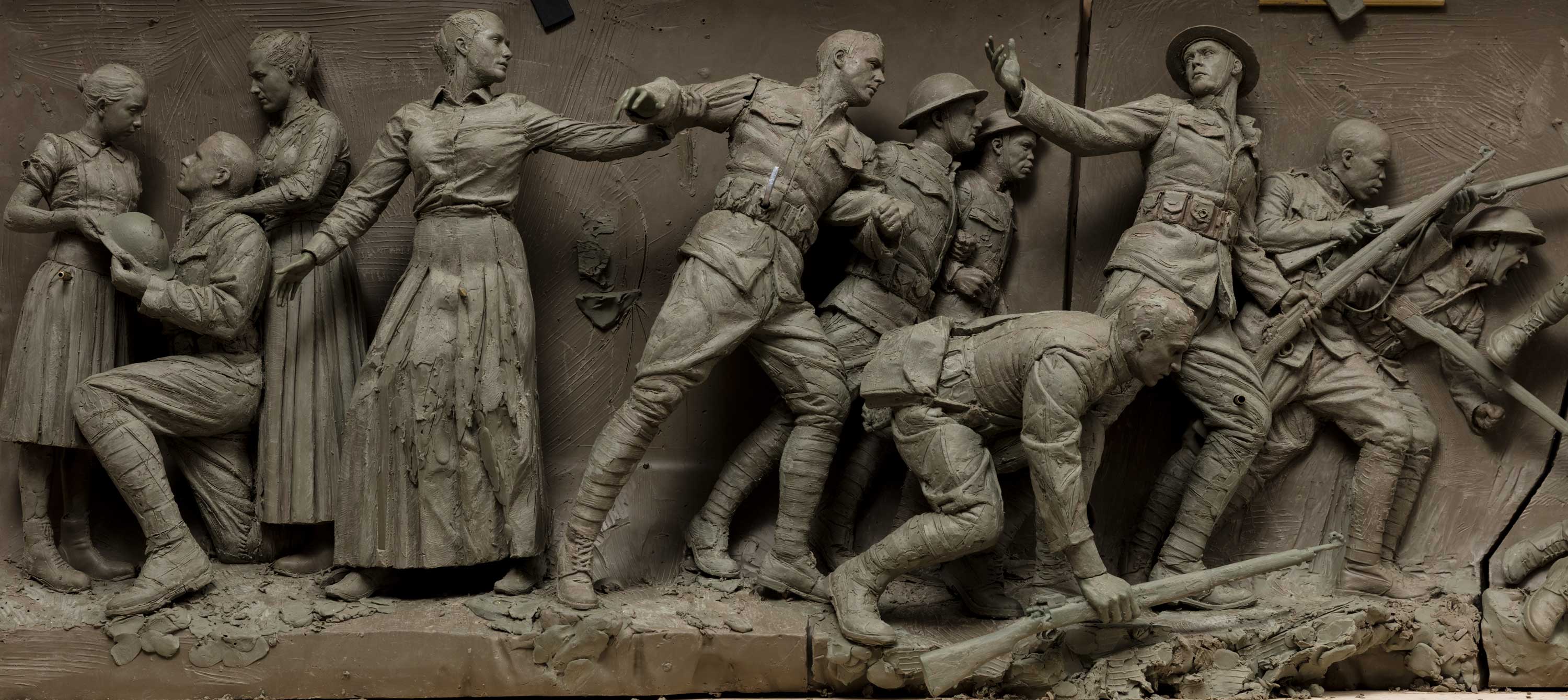

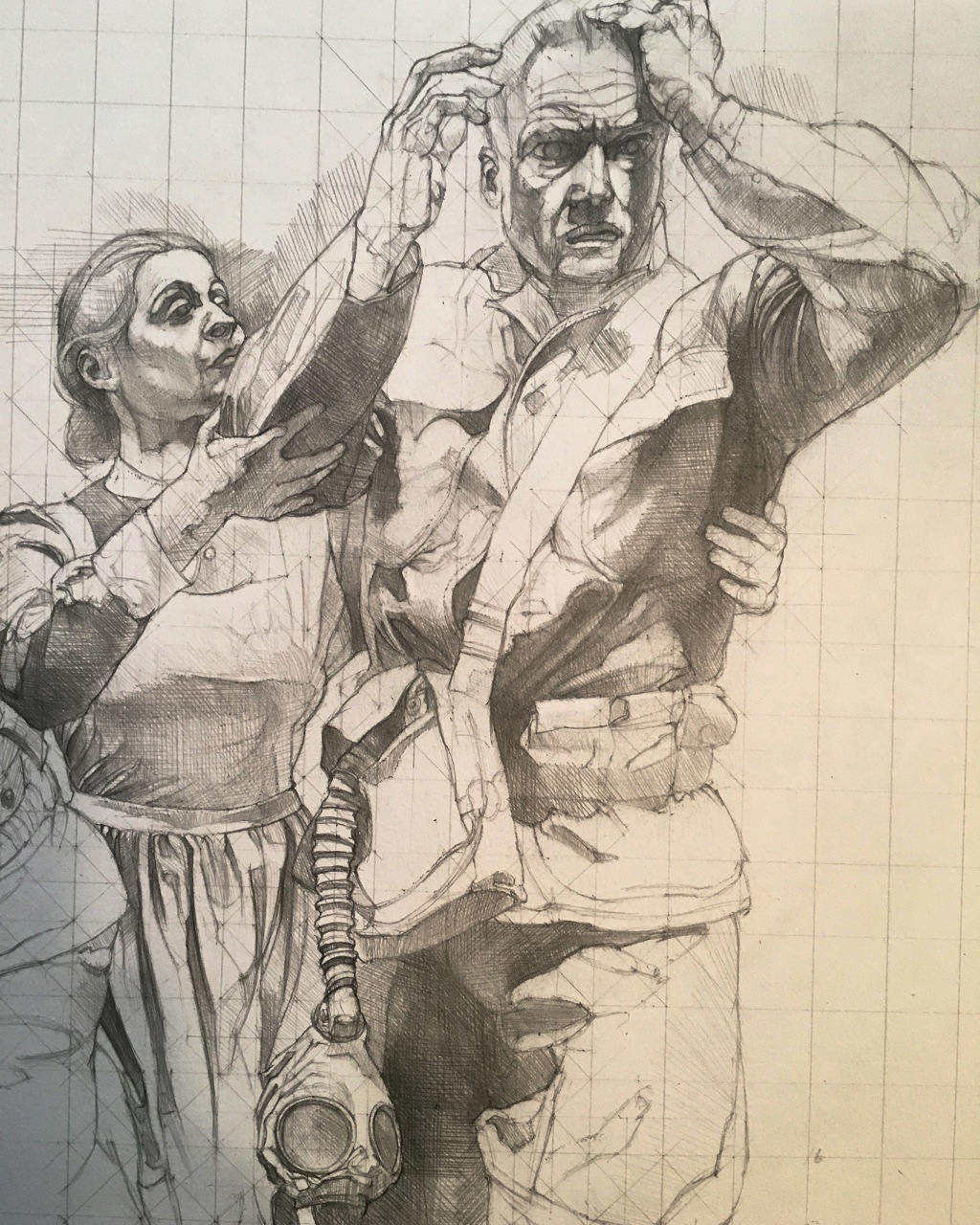

In the dynamically realistic bodies of the figures in “A Soldier’s Journey,” Howard puts to expressive use the knowledge of the body’s language he gained in the course of sculpting the static, idealized bodies. They are relatively inexpressive, or at best minimally expressive, the gestures of their arms and the expressions on their faces relatively restrained, peculiarly beside the point of their magnificent torsos — of the mythical gods and goddesses (Apollo, Aphrodite, Mars, and Hermes) and symbolic figures (Persistence, Stubbornness, Mindfulness, and Ego) he made before he decided to deal with actual human beings and actual human experience.

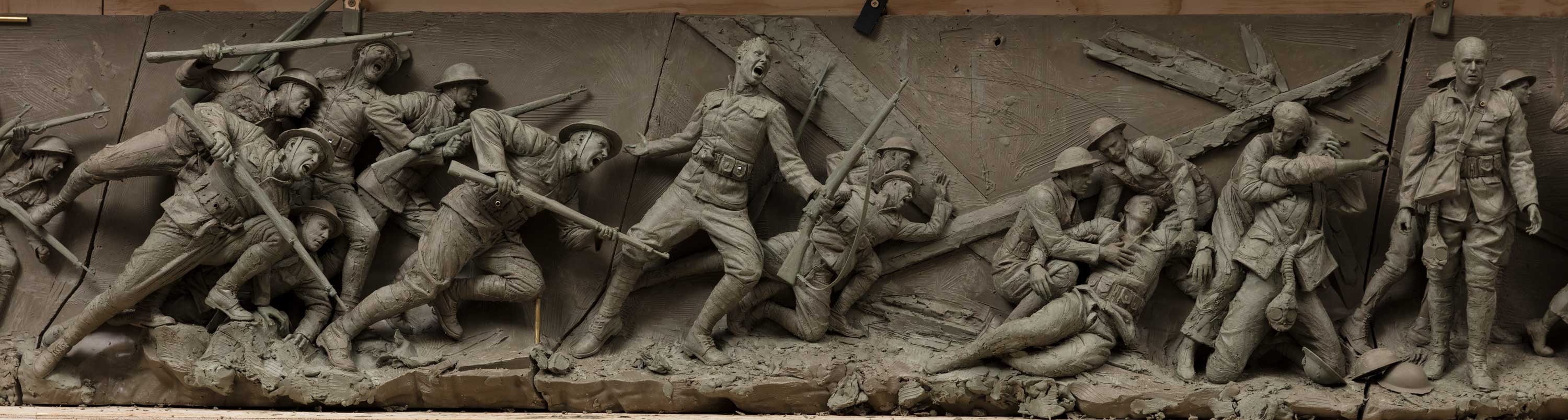

Classicism means control and poise, and while Howard’s modern figures are in control of themselves — especially his women — they are also much more lively than his classical figures. Howard’s soldiers have great egos — but clearly not as great as those of the omnipotent gods and goddesses — but they are instinctively driven: on the move rather than passively given. War, after all, is an expression of aggression, which Freud said was a manifestation of the death drive — conscienceless killing is war’s unconscious purpose, however much it may claim to serve a conscious purpose.

Engaged in war, and with that facing death, Howard’s mortal men and women are convincingly alive — and believable — in a way his immortal gods and goddesses can never be, for if one can never die one doesn’t know the value of life. Immortality, after all, is a wishful delusion, and gods and goddesses are mythical, not to say make-believe fantasies. They appear in Homer’s Iliad and Odyssey — war stories — standing high above the war even as they sanction it and support its heroic leader.

Related Article on Realism > How Drawing Influences My Sculptures

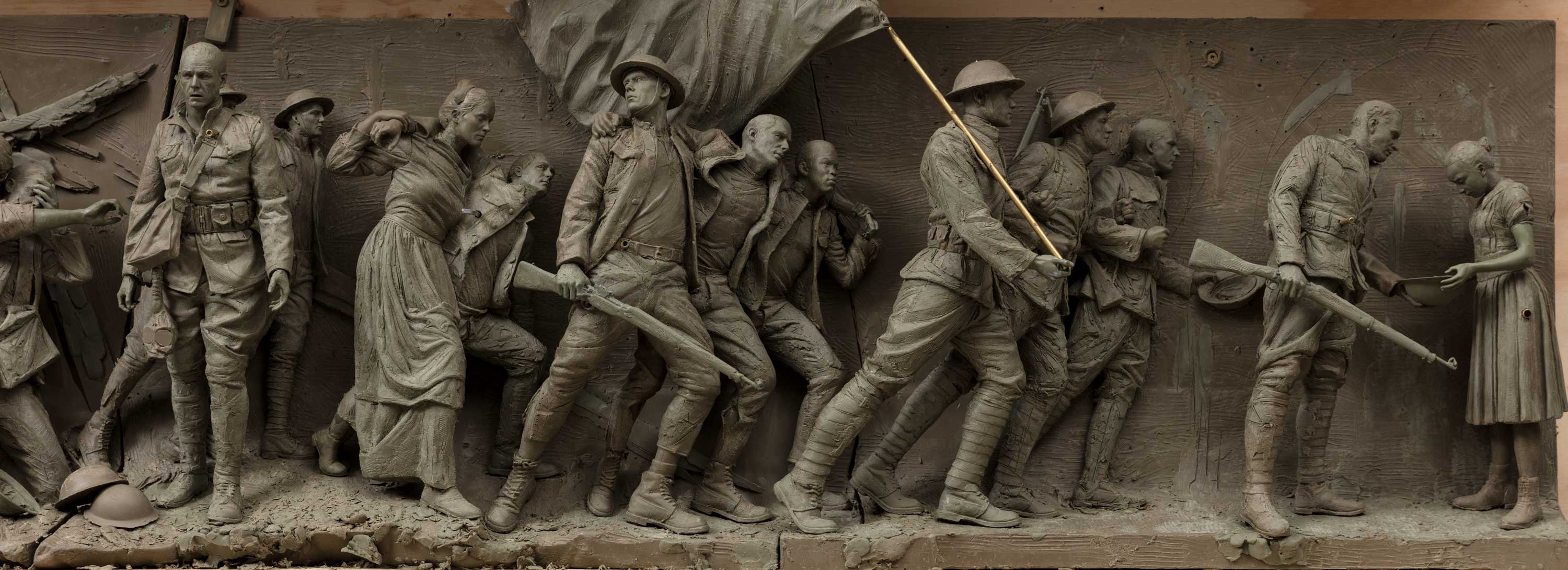

In Howard’s war story, the latter is the unbent figure between cross and flag, suggesting that he has been raised from the dead — resurrected like Christ, inviting us to worship — certainly admire — him. Standing out of the scene however much he is a part of it — he would make a good target for the enemy, for he’s unprotected — he is peculiarly godlike, the unmoved mover of the work.

All the other soldiers are on the move — seen in action, fighting without pause, completely absorbed in the war — while he stands apart, isolated in glory. Presiding over the soldiers — he is their commander — he implies that they will be victorious, however many of them will die on the battlefield. To die in the service of one’s country is to have what Aristotle called a noble death. It is to become as noble — heroic, outstanding, memorable — as the upright leader. Many of them crouch, bringing them close to the earth, as if in unconscious anticipation of being buried in it.

The only other majestically “unbent” figure is the heroic nurse. She appears at the beginning of the play, coming on stage from the left, in contrast to the heroic leader of the charge to the right, where he will go off-stage. The alpha and omega of the work — a sort of royal couple — they signify that one can endure and survive war, however much suffering and death it causes.

Follow the making of the National WWI Memorial at sabinhowardsculpture.studio.

About the Author: DONALD KUSPIT is the Distinguished Professor Emeritus of Art History and Philosophy at the State University of New York at Stony Brook and the senior critic at the New York Academy of Art. He has doctorates in philosophy (University of Frankfurt) and art history (University of Michigan). Among his many books are The End of Art (2005) and The Cult of the Avant-Garde Artist (1994).

Article excerpt reprinted with permission from Fine Art Connoisseur magazine