By Adrienne L. Childs

Images of black people have long been a significant feature of European fine art. Never simply representations, they have come down to us through a politically charged and aesthetically complex history that was explored in the exhibition “The Black Figure in the European Imaginary” (Cornell Fine Arts Museum at Rollins College in Winter Park, Florida, 2017). It gathered 31 paintings, sculptures, prints, and decorative artworks that span the 18th and 19th centuries. Though produced by European artists, all were from American collections, both public and private. The resulting assemblage offered a fascinating glimpse into how the European “imaginary” impacted our collective perception of black people on a global scale.

To be sure, individual black people were known in Europe during this period, but modes of understanding were mediated by their status as slaves and servants, or as exotic foreigners, and were frequently framed by preconceived ideas. Consequently, artists and viewers alike depended upon facts and fictions filtered through the lens of colonialism, imperialism, slavery, abolition, and, frankly, racism. Interestingly, the resulting imagery generally avoided the style of racist exaggerations prevalent in America during the same era. Black figures by European artists were far more likely to be depicted individualistically, often with depth and dignity. Yet, compelling as many of these images were, undercurrents of objectification, emphasis on servitude, and hierarchical attitudes about race resulted in images that were complicated, ambivalent, and nuanced.

The Cornell exhibition assembled a sampling of images in four general categories: slaves and servants, artists’ models, historical and literary figures, and exotic themes. Until the 19th century, the most common role for black people in art was that of servant or slave. It was considered a status symbol for wealthy Europeans to own or employ an exotic, well-dressed black servant such as the sitter of the spectacular “Portrait of a Youth in an Embroidered Vest” (1785) by French painter Marie-Victoire Lemoine.

While the identities of many of the individuals represented in works like this are now lost to history, there have been unsubstantiated claims that this is a portrait of Zamor, servant to the infamous Madame du Barry, mistress of King Louis XV. Regardless of his name, this young man’s sumptuous clothing and young age indicate that he is a court servant whose elegance signified the status and conspicuous wealth of his master. The fact that he is represented as the subject of a portrait is striking, as black servants were most often depicted as adoring companions, luxury appendages for the elite sitter.

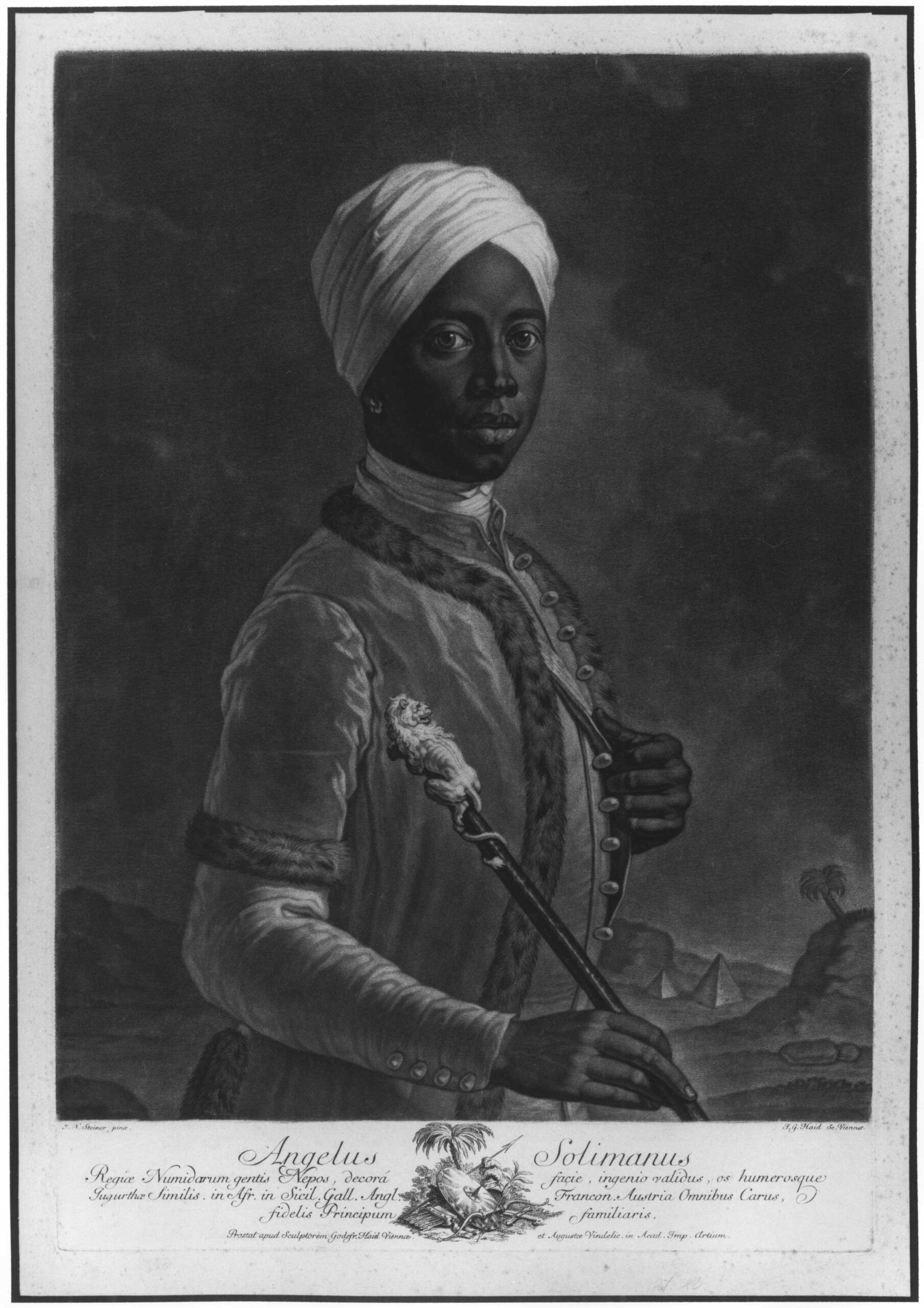

A fascinating diversion from this anonymous young man is the case of the black courtier Angelo Soliman, whose biography is well known. Represented in Johann-Gottfried Haid’s print after Johann Nepomuk Steiner (1760s), Soliman was a slave who was freed, educated, and eventually held a position in the Viennese court of Joseph Wenzel, Hapsburg prince of Liechtenstein. While he was held in high regard and enjoyed much personal and social success, the elaborate costumes Soliman wore at court were designed to emphasize his exoticism, despite his individuality.

While images of blacks living in Europe spoke to expectations of exoticism, paintings of black people in the colonies — such as Italian painter Agostino Brunias’s “Linen Market, Dominica” (c. 1780) — provided Europeans with a slice of life as it was thought to exist in their nations’ empires overseas. Brunias’s crowded scene depicts a spectrum of European, black, and mixed-race men and women as they interact in the British colony of Dominica.

Under the glorious West Indian skies, varieties of fabric are being sold and worn by women whose clothing reveals their place in a hierarchy of social status and beauty. The fashionable finery of the lighter-skinned women flaunts their privilege above those of darker hue, dressed in humble apparel. In an effort to illustrate the developing West Indian society as appealing in all its complex layers, Brunias also touches upon some disturbing aspects of colonial life. Although his aim was clearly to produce a sanitized view of social classes and racial interactions, avoiding the violence and inhumanity of slavery, he reveals the troubling evidence of a culture that grew out of generations of “unnaturally” liaisons between white men and slave women.

Of course not all Europeans supported slavery. British artist John Phillip Simpson’s “The Captive Slave” (1827) is a testament to the strong abolitionist movement in Europe, particularly England. Simpson’s romantic painting depicts a seated, shackled man whose plaintive gaze evokes the human tragedy of slavery itself. Though he is dignified and has great physical presence in this large painting, this unnamed man remains passive and fettered, reliant on the actions of others for freedom.

Interestingly, the model was reportedly the African American actor Ira Aldridge, who established himself in England as the first black man to play Shakespeare’s Othello. A man of great individuality and tenacity, Aldridge forged a career in Europe against all odds and spoke out against American slavery. Aldridge himself was represented in the exhibition in an anonymous print.

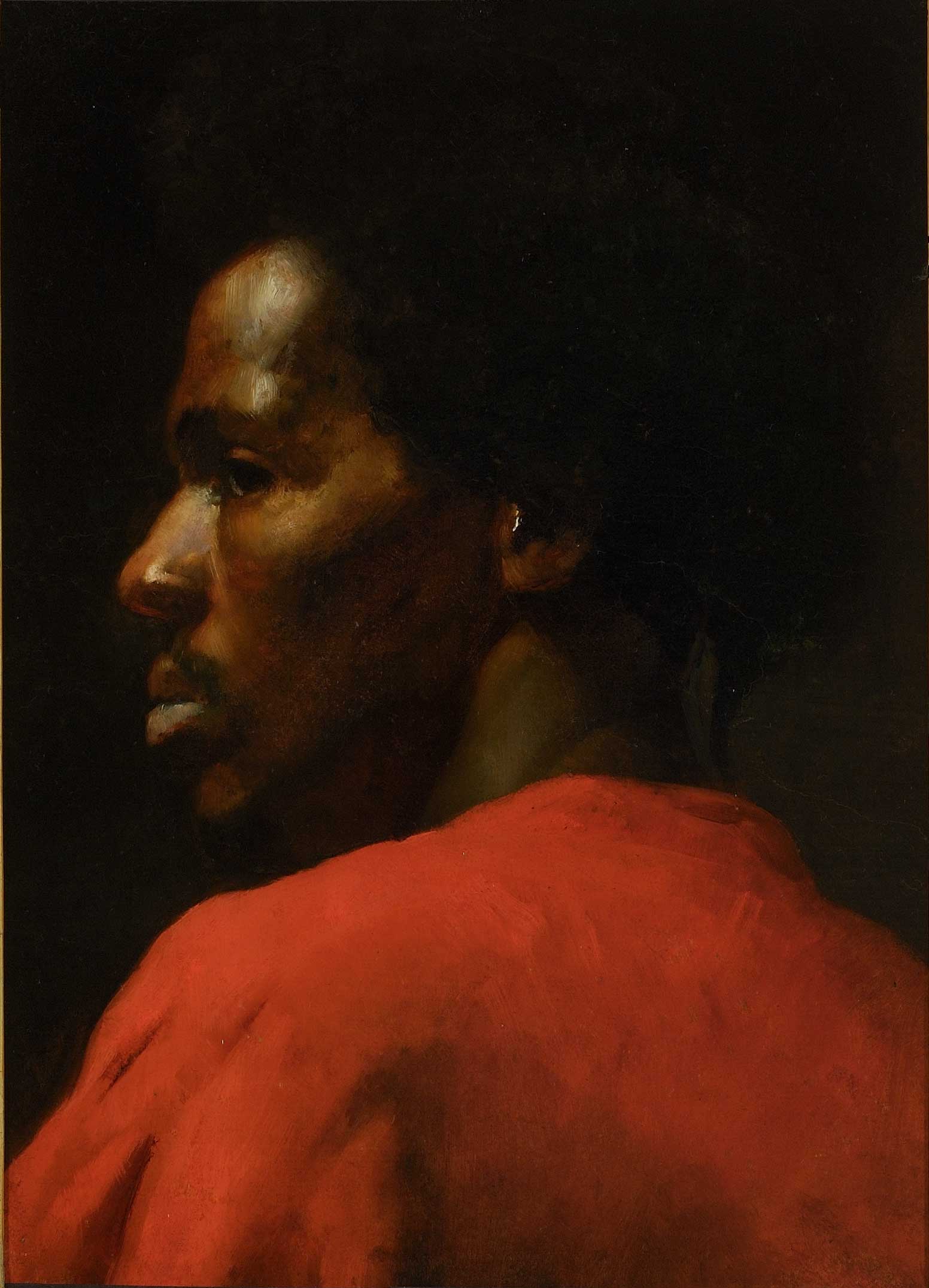

As the 19th century progressed and themes of exotic peoples and places became more popular in Europe, so did the demand for black models in major art centers like Paris and London. Black models were sought after for studies, as well as for multi-figure compositions. French academic artist Léon Bonnat’s “Head of a Model” (c. 1857) is a stunning portrait of an unknown man in profile. His red garment symbolizes passion and perhaps points to an imagined exotic origin. It also provides a sumptuous contrast to the richness of skin tone and the dark background from which this beautifully rendered figure emerges.

“Head of a Mulatto Woman” (1861) by the English painter Joanna Boyce Wells is a portrait of Fanny Eaton, who modeled for such Pre-Raphaelite artists as Dante Gabriel Rossetti. Because of her racial ambiguity, Eaton posed for figures of diverse ethnicities such as Egyptian and Hebrew women. Indeed, she is one of a few European models of color whose biographies have been preserved.

Dr. Fritz Daguillard is a Haitian-born physician who has collected paintings and prints of blacks by European artists for the past 70ish years. His collection is personal and represents his lifelong quest to identify and preserve dignified images of black people in European, particularly French, art. He has a particular interest in images of the Haitian revolution and of its famous leader, Gen. Touissant Louverture, who is represented in more than 40 of Daguillard’s prints.

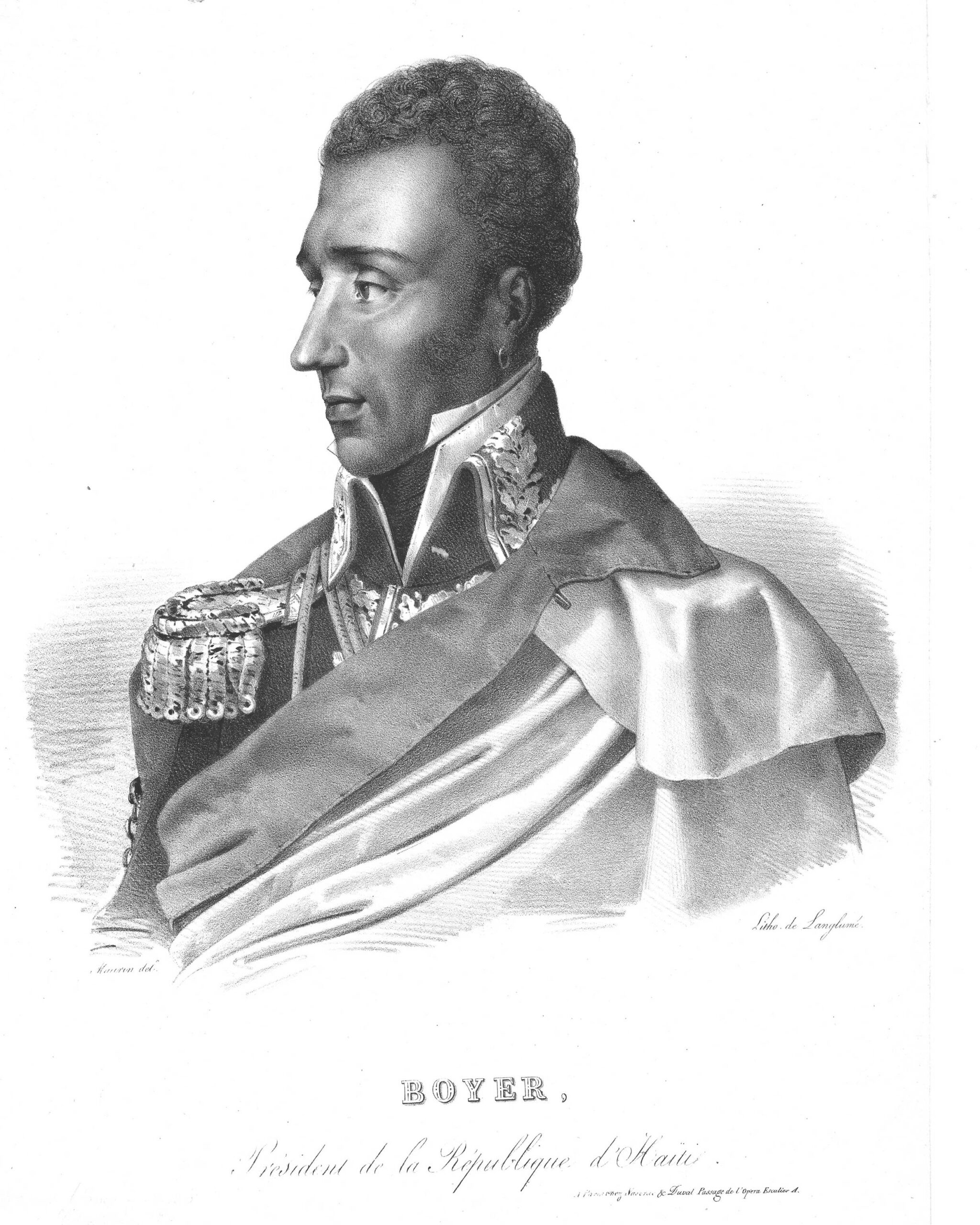

In addition to one of the most important images of Louverture by the French printmaker Nicolas Eustache Maurin, the exhibition contained a 19th-century print of the lesser-known “Boyer, Président de la République d’Haïti,” made by his brother Antoine Maurin. Of mixed French and African heritage, Boyer is depicted heroically in military regalia. He was part of the revolutionary leadership of the French colony of St. Dominge, which struggled in a war for independence from France.

Through the efforts of Louverture, Boyer, and others, this became the first successful slave revolution in the western hemisphere and formed the independent nation of Haiti (1804). Also noteworthy in the Daguillard Collection are three portraits of Alexandre Dumas, one of the 19th century’s most prolific writers and important cultural figures, who was also of mixed-race heritage.

Fascination with the exotic was a defining ethos of the European imaginary during the 18th and 19th centuries. Thus one key focus of the exhibition is black figures in Orientalist art, perhaps the period’s most enduring and influential form of exoticism. The “Orient” referred to the Mediterranean coast of North Africa, Turkey, and the Middle East. Since much of this terrain was in Africa, naturally we find a critical mass of black figures in this genre.

Ornate portraits of “Oriental” characters such as the Italian artist Nazzareno Cipriani’s undated “Head of a North African Woman” were popular among collectors of the era and remain so now. Lavishly costumed men and women, such as those by Spanish watercolorist José Tapiró y Baró emphasize the ornamental character of exotic types adorned in jewelry, fabrics, and other accoutrements captivating to European viewers.

French Orientalist Travelers

Jean-Léon Gérôme’s “Moorish Bath” (1870) is a classic emblem of the Orientalist enterprise, which often combined black and white “odalisques” in sensuous harem or bath settings to the delight of patrons, who seemingly could not get enough of this imagery. The black servants who attended the white women symbolized the exoticism, eroticism, and decadence of the Orient. Gérôme’s documentary realism is legendary, yet, despite his convincing details, he actually constructed his compositions by studying models in his Paris studio, underscoring the powerfully fantasizing aspect of the Orientalist imagination.

“The Black Figure in the European Imaginary” aimed to initiate a dialogue with American audiences who are perhaps more familiar with how American artists have characterized African Americans — as opposed to the tropes and types ascribed to Africans in Europe. The images and objects in the exhibition, therefore, have offered a multi-dimensional view reflecting the deep, wide, and diverse history of black people who were simultaneously interconnected by the monumental historical episode of slavery, yet scattered by it throughout the Atlantic world.

***

This article originally ran in our sister publication, Fine Art Connoisseur. Subscribe to the magazine here.

Become a Realism Today Ambassador for the chance to see your work featured in our newsletter, on our social media, and on this site.