“After getting clean and sober, the haze lifted and I was able to use that life experience of sad emptiness to feed my artwork. The struggle then had meaning.”

BY ANNIE MURPHY ROBINSON

Although I wasn’t born an artist, I believe I was born with a yearning to create. I was raised in the tiny community of Heron, Montana in the 1970s and spent my monthly allowance on art lessons from Mrs. Mullens, so I could draw animals. I also begged my mom to get me the “How to Draw” books whenever we went into town, and with these I learned how to draw faces. I continued to draw throughout elementary school and considered myself pretty good — but of course I only had five other students in my grade to compare myself to.

In 1979 we moved to Tucson, Arizona, and I started middle school. I felt out of place, like I didn’t have the right clothes, and I felt very alone. That’s when I started sneaking out with my older brother and his friends, smoking pot and drinking. I don’t remember drawing during this period, although I still have a few drawings I managed to do.

We moved again to Phoenix, where I started ninth grade a few weeks late, causing me to miss basketball tryouts (the one sport I loved). I tried out for cheerleading, but I didn’t make it (and I just knew the older girls laughed at me). At that point I gave up, found the partiers and began a journey that took years to end. By the next year I had dropped out of school, and was on the streets of Phoenix with my best friend, couch surfing, drinking, and using drugs. From Phoenix we went to San Francisco and stayed there for another year or so, until I got picked up on a school sweep and went to juvenile hall. The only drawing I did then was on my cell walls. I finally moved in with my aunt and uncle but eventually drank my way out of their house and ended up in continuation school. I took my GED and got emancipated at sixteen-and-a-half. From there I started going to junior college and took an art class. Again I compared myself to others in my class—this time they were older than I—and thought I came up short.

My drinking and drug use started spiraling out of control, so I joined the Army at seventeen to get away from my friends who were all starting to use harder and harder drugs. Although I enjoyed the military, I managed to drink my way out (not an easy task). I ended up moving to Lafayette, Louisiana with a man I met in the Army, and started going to college again.

While there, I majored in art and managed to graduate with my B.A. in art with a core concentration in painting. During that time I quit drinking for about a year and a half, but continued to smoke pot daily and do whatever drugs were available. Just as I was about to graduate I began to drink again. I was so drunk at my solo show for senior reception I don’t even remember it. Somehow I did manage to get a feel for painting, concentrating on things I would find or had (underwear, beer and wine bottles, newspapers, etc.)

After graduating, I ended up in Sacramento, California (after the boyfriend went to rehab) where my mom and brother were living. Upon arrival I continued to drink, which in a short period of time led to a failed relationship, an abortion, more guilt and finally an awareness that it was either quit drinking or die. I sobered up long enough to get married and pregnant, but the marriage didn’t last for very long. But after my daughter was born in 1996 I finally gave up drinking.

Why the history of Annie? Because although I have always loved art, when I drank I could only hope to be a good artist. It was impossible to work to my full potential. After getting clean and sober, the haze lifted and I was able to use that life experience of sad emptiness to feed my artwork. The struggle then had meaning. I used all the energy it had taken to keep me loaded and applied it toward my art. I was a survivor and no longer a victim.

With some sobriety I applied to the Master’s program at California State University, Sacramento and was denied. This was unexpected and I found myself wanting to use, so I called my old drug connection. He said I was doing really well and he wasn’t going to be the one to enable me to give up. I am grateful for his insight.

Wanting to prove myself, I worked on painting for two years in my garage, took a few college classes as an undeclared graduate student, and applied again for the Master’s program. This time I was accepted!

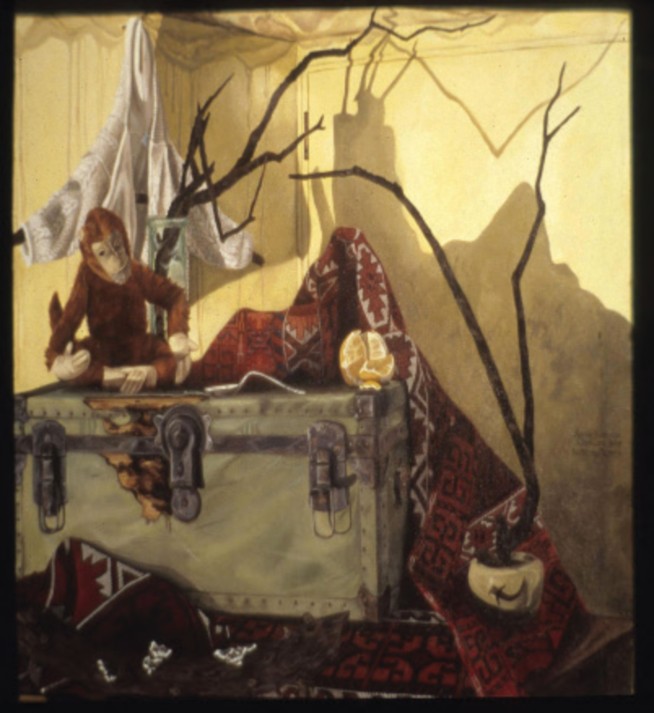

I spent every available minute dedicating myself to art, finding out who I was through studying other artists and practicing my craft. I struggled. It seemed to me that everyone else in the MA program had a clear and concise vision of who they were through their work, and I didn’t. I found myself looking to other artists I admired, but wasn’t looking at my own life. I didn’t feel my experience was worthy. The best of my attempts was a still life of a stuffed monkey, a bent spoon (to symbolize addiction), an orange (what you need to eat to keep giving blood to buy heroin), and my daughter’s sweater (standing in for childhood).

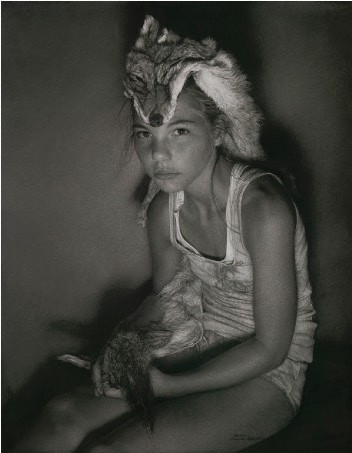

Shortly after that, I stopped painting and started drawing, concentrating on form. I submitted a large drawing I did of my daughter in a dirty flower girl dress and won first place at a student purchase show.

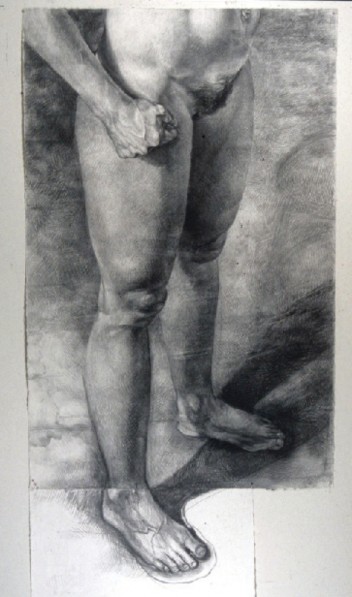

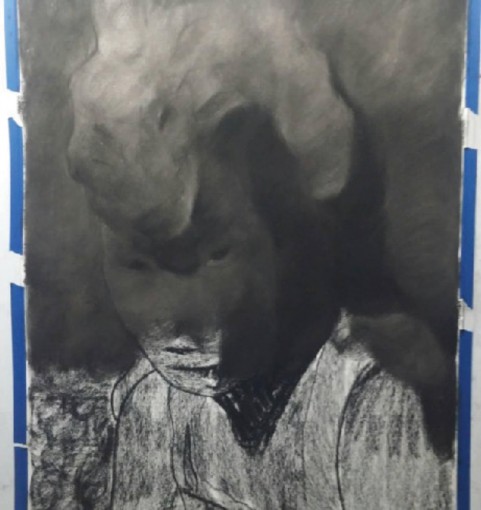

Something clicked inside and I felt motivated and acknowledged. I then started drawing myself from a large mirror (sometimes two for my back body), and gave up painting altogether. I drew large crosshatched charcoal bodies, often truncating them, and every so often I included my head.

You can see the vine charcoal falling off of the paper here, I also ran out of room for the foot which I added. This was never shown. I am including this piece because every piece is important, even if it doesn’t turn out.

After graduating with my Masters, I went to an artist’s opening and met artist Troy Dalton, who would become my mentor. I went to his house on weekends and drew in his large studio (after I spent at least two hours cleaning his kitchen as “payment”). He encouraged me to try sanding the charcoal into the paper and I never looked back.

My first solo show was at a local community college. I included work from my senior year and some new work. From there I built my resume at various non-profit galleries. I finally got my first “for profit” show in 2006 at b. sakata garo in Sacramento, where I sold every piece I brought to the show.

I had to learn how to frame my work for this show and found it so time consuming that I swore from that point on to have my work professionally framed. I frame each piece as I draw. Since then I submitted my work to MANY galleries and finally got a chance to show my work in San Francisco, and continued to show there until the gallery closed. I began refining the sanding technique and continued to draw the form, mainly my daughters and old toys and an old doll house that I found.

I experimented with using the sanding technique with pastel as well, but for health reasons, I no longer use it.

The “Sasquatch” series was a big breakthrough for me. My husband — my second and last! — took photos of me in the woods and in France (thanks to my sell-out show at b. sakata garo!), and I began drawing from these images. In creating the first piece “(Sasquatch, Tahoe)”, it brought up some repressed memories from my childhood. I was sexually abused by a family member in second grade and would hide in the woods to avoid seeing this person when my parents were at work. In drawing this piece, I began to relive that terror, and realized that through this piece I could change my story. I was no longer hiding. Instead, I was at one with the woods, not afraid of my nudity or of my abuser. I felt empowered, meeting the gaze through my portrait, daring him to come get me. My hands and feet are disproportionately large, giving the figure more power and strength. It was only after finishing the drawing that I saw these things and placed them in context with what I had been feeling while creating the work.

I did quite a few of these drawings and ended the series with Sasquatch Dordogne. In this last piece, thanks to the drawings and therapy, I’m in proportion and turning away from the viewer, and have taken back my power.

Following the Sasquatch pieces, I started drawing my daughters. I have documented their growth through my experience of them. Being an artist and a mom has been a difficult path. Art takes time and dedication, and I noticed guilt rising up every time I went to work in the studio. I started setting a timer to play with my girls because my time in the studio far out-weighed the play time I had designated. The timer allowed me to not stress about drawing and I was able to enjoy playtime.

In the beginning I drew much more gesturally, including how I sanded the charcoal into the paper. I invested in a good camera and lights and my art became much more refined. Through this refinement, I also increased the amount of time it took to finish a drawing. I do track time now, just out of curiosity, and the gallery owner that I show with uses this as a selling point as well. It is in the journey that I live, focus and don’t think about anything else but the image.

My Process

Getting a good photo is the first must—I blow it up to about the size I want to draw it, and it needs to stay sharp.

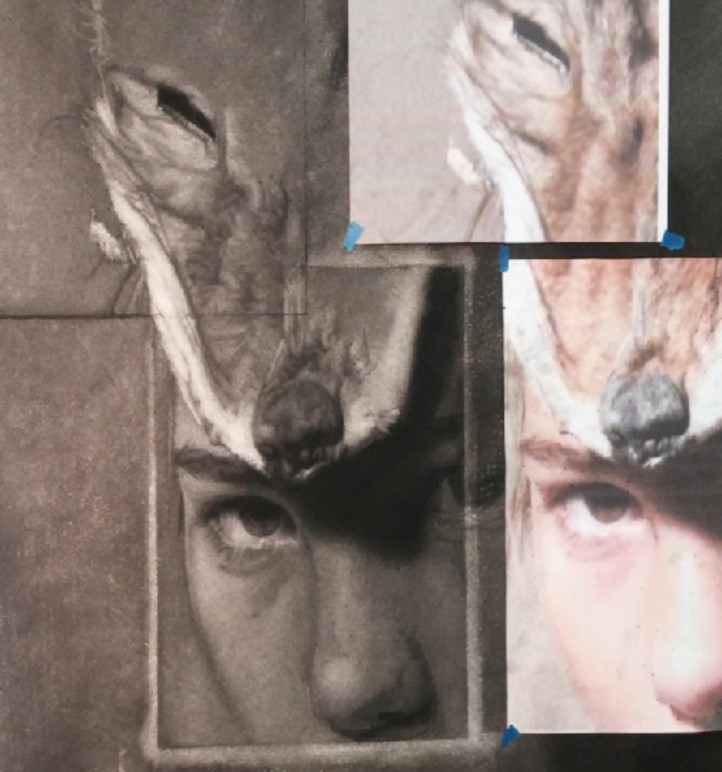

I use a very small print of the entire piece, and I blow it up on a projector. (I use a very poor one so I don’t get mired down in detail!) I fit it onto a fresh piece of 300 gm BFK Reeves printmaking paper and outline it in compressed charcoal. I then use an 8×10 print to block in the lights and darks. I then use 400 grain sandpaper to hand-sand the entire thing, to grind in the charcoal and to sand off the sizing on top of the paper.

I then blow up a shot around the main eye and place it on top of the drawing to see if it is a good size. I then put the print on top of the paper and outline it, making sure that the paper I am working on is level, as well as the print I am placing on top of it.

I darken the center (the pupil) and then cover everything with another layer of charcoal, and sand it down to a medium grey shade. Then I start . . .

I draw every day. I average about 25 hours a week. I work full time. I realized that I don’t have time to wait for the muse. I also don’t have a critique coming up at school to motivate me. I know that when I start working, even if I am not into it, I soon will be.

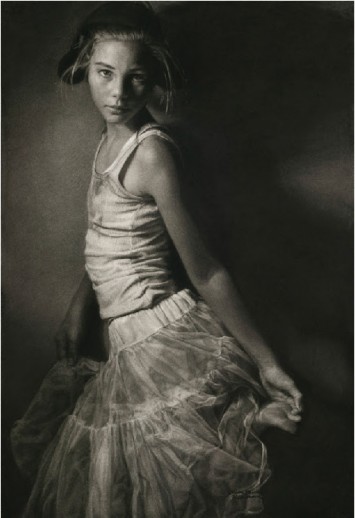

Emily at thirteen. I really struggled with the light on her face and getting the lace right.

Annie Murphy Robinson, “Emily and Shadows,” 2014, charcoal on paper, 35 x 42 inches.

Behind her is tumbleweed I picked up on the way back from L.A.

I have discovered that when I draw what I know, what I love, what resonates with me, I create authentic work. I validate my life and experiences — good, bad, and indifferent — through my art. We all have a voice; we all have experiences that with regular practice will show up in our work. My advice is don’t wait for a good idea, don’t second-guess yourself, do the work and it will come.

Website: http://www.anniemurphyrobinson.com

This article was originally published in 2017

Visit EricRhoads.com (Publisher of Realism Today) to learn about opportunities for artists and art collectors, including Art Retreats – International Art Trips – Art Conventions – Art Workshops (in person and online, including Realism Live) – And More!