By James Andrews

Classical realism, academic art, the atelier method — whatever you choose to call it, it’s a fact that the tradition of realist art instruction passed down through the ages by individuals and institutions such as Paris’s Ecole des Beaux-Arts nearly died during the 20th century. The rise of modern art (and perhaps a bit of professional jealousy) fostered not just an organic shift away from some traditional methods, but also the intentional abandonment of disciplined study altogether. Accomplished artists, classically trained themselves, eschewed that training for their own students, university programs urged pupils to break free from old ways, and soon the powers-that-be were telling the public that the academies’ realism, in all its painstaking beauty, was simply pedestrian. It became the art of a dead culture.

Thankfully, the tradition was preserved through the efforts of artists like R.H. Ives Gammell (1893–1981), who criticized the new methods, not always fairly, as “clumsily applied daubs of paint.” From his atelier in Boston’s historic Fenway Studios, he — and a few other dedicated believers scattered around the globe — sustained the knowledge, somewhat like those Irish monks who copied Latin manuscripts after the Roman Empire’s fall and thus kept Western civilization alive.

Still, at the dawn of the 21st century, Gammell’s brand of classical training was largely invisible to the public. If you wanted to pursue it, you really had to put in the work to find opportunities. Library card catalogues might steer you toward dusty volumes of masterworks by William-Adolphe Bouguereau (to name just one 19th-century exemplar), but the instant access to such imagery we now enjoy through the Internet was still evolving. There was no easily discovered list of schools or individual masters who accepted students, and there were no degree programs focused on this method — a real problem in a society that considered formal degrees an absolute necessity for all subsequent life paths.

All of that has changed. Today a Google search of “atelier art training” returns approximately 27 million results, ranging from websites to videos to articles. In fact, the difficulty now lies not in finding information about the tradition but in navigating the surging ocean of it. Our Information Age has also made in-person training only one of several options; the pandemic accelerated the quality and breadth of online learning, forcing most brick-and-mortar schools to embrace it or die.

Now that we all have access to some of the world’s best instructors in our own homes, the questions posed by budding students are different: Which master should I study with? Are asynchronous tutorials enough, or is an interactive course taught over Zoom a better fit for me? What about individualized coaching sessions? Is a formal degree really necessary for where I am heading?

Today’s atelier movement offers many options, though the most significant choice remains the decision to train in the first place. It’s helpful to start the journey with talents who have been doing this for a while, who match your needs best, and who are engaged with the latest techniques, both in person and online.

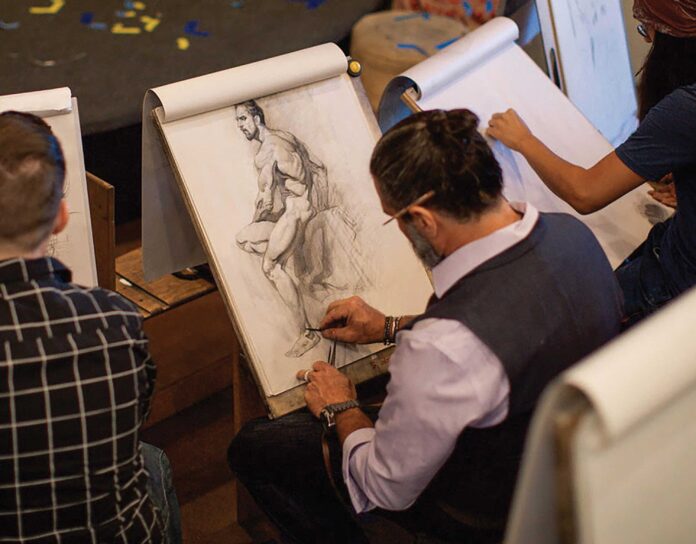

Jeffrey Watts (b. 1970; shown at top) was one of the first Americans to see a need for classical realist training and then jump right in to meet it.

Mandy Theis (b. 1985) can trace her desire for classical training back to a second-grade field trip to Ohio’s Dayton Art Institute. She remembers how the paintings made her desperately want to create works just like them. Yet school art classes never seemed to get her to the heights she sought, and she began to feel she might not be capable of that level of artistry — that she didn’t have “it.”

Ask Scott Waddell (b. 1981) how he came to the atelier world and you’ll get the impression it actually found him. A witty conversationalist, he “seems to recall maybe seeing a brochure for the Florence Academy of Art when I was attending Florida State University. I didn’t even know the word ‘atelier’ back then, to be honest.” We shouldn’t let Waddell’s self-deprecation fool us, though; he made good use of that brochure and attended the Florence Academy for a time. Later, he spent years taking odd jobs and skipping meals to afford training with Jacob Collins in Collins New York City studio.

Juliette Aristides (b. 1971) has combined her old-school classical training and her vast experience teaching in her own atelier to create the Online Aristides Atelier, launched in partnership with the art instruction portal Terracotta.

Information: wattsatelier.com, scottwaddellfineart.com, aristidesarts.com, schoolofatelierarts.com. To learn more about the atelier world, follow these podcasts: artgrindpodcast.com; suggesteddonationpodcast.com; theundrapedartist.podbean.com

Learn from Juliette Aristides through these books and art workshop videos available through PaintTube.tv: