An essay by artist Tim Rees, including three pieces of expert painting advice you’ve not likely heard.

By Tim Rees

Paintings that attract us are well done and elicit some sort of positive emotional response. Our inability to describe these qualities elevates certain paintings to the echelon of beautiful magic.

We all started our lives believing in some sort of magic. The world had endless discoveries to be made, and when there was something that couldn’t be explained, a magical twist was induced. As we grow, we never really let go of that thrill of the unknown or new, even if it remained with us only on a very small scale. This is why we are so enchanted by some paintings.

A painting creates a new world, one that has existed (to some degree), or one that could never be. It’s often a world of beauty, and one that resonates with the very core of humanity. This coupled with the obvious skill of a well-crafted painting creates something that is nothing short of magical.

I often encounter people who have decided to pursue painting later in life. With their age comes experience, opinion, and a uniquely beautiful viewpoint of the world. These students of painting have a magical story they wish to tell, but don’t have the technical ability to do so. They are so enchanted with painting that seeing a great work of art often leaves them with a feeling that the skill level is far beyond what they could ever hope to achieve. It is not understood. It is marveled at. It is magical.

While I firmly believe paintings should never lose their magic, I am saddened to hear the oft-repeated dismissals of the work of professional artists by students: “They were born with talent” or, “They put in so many hours, I don’t have that much time left” or, “They were able to study somewhere I could never go,” and so on. All of these are variations that distance students from what they perceive as “the unattainable goal of being a professional (or skilled) artist.”

The minute a student gives in to any of these statements or their variations, they have taken the first step toward a self-fulfilling prophecy. I remind my students that while art was an interest of mine it was by no means my strongest suit, that I have not been painting relatively long (about seven years now), that I painted in my spare time while juggling a family and full-time job, and that I couldn’t afford to go to art school.

When one decides to dispense with the idea that becoming a painter involves some mysticism, real progress can be made. My painting career began with one assumption: There are very skilled artists painting realism today, and if they learned how to do it, so can I.

I just needed the understanding, or the science. As I later found out, this was the mentality of Harry Houdini, the formidable magician. He had done what I did — picked up the how-to books, performed everything they described until tricks could be done without them, and then started to make up new things. This brings up another habit students tend to have — accumulating a great library of expensive books that go unread. Occasionally they have been read, but almost never have they been copied or the processes replicated. This was one of the pillars of art education in ateliers and academies from the 1500s to the 1800s: Want to learn to draw and paint? Copy the master. Once you begin to learn how each “trick” is done, you start to reveal the magic.

This was the foundation of my art education. Read and replicate. Watch others make certain mistakes and don’t do them. Review each painting and compare to masterworks. Bit by bit my knowledge grew. Teaching cemented this knowledge and helped it grow. I was always too reserved to make any statement for which I couldn’t cite a professional or dead master as the source of the information. Every so often I would write down everything I knew about a particular topic to find the gaps in my knowledge, and I encouraged my students to do the same.

All this is not to say I didn’t have to figure a few things out myself. Hopefully I can reveal some of them to save you a bit of trouble. Here are three pieces of art advice that most students haven’t heard.

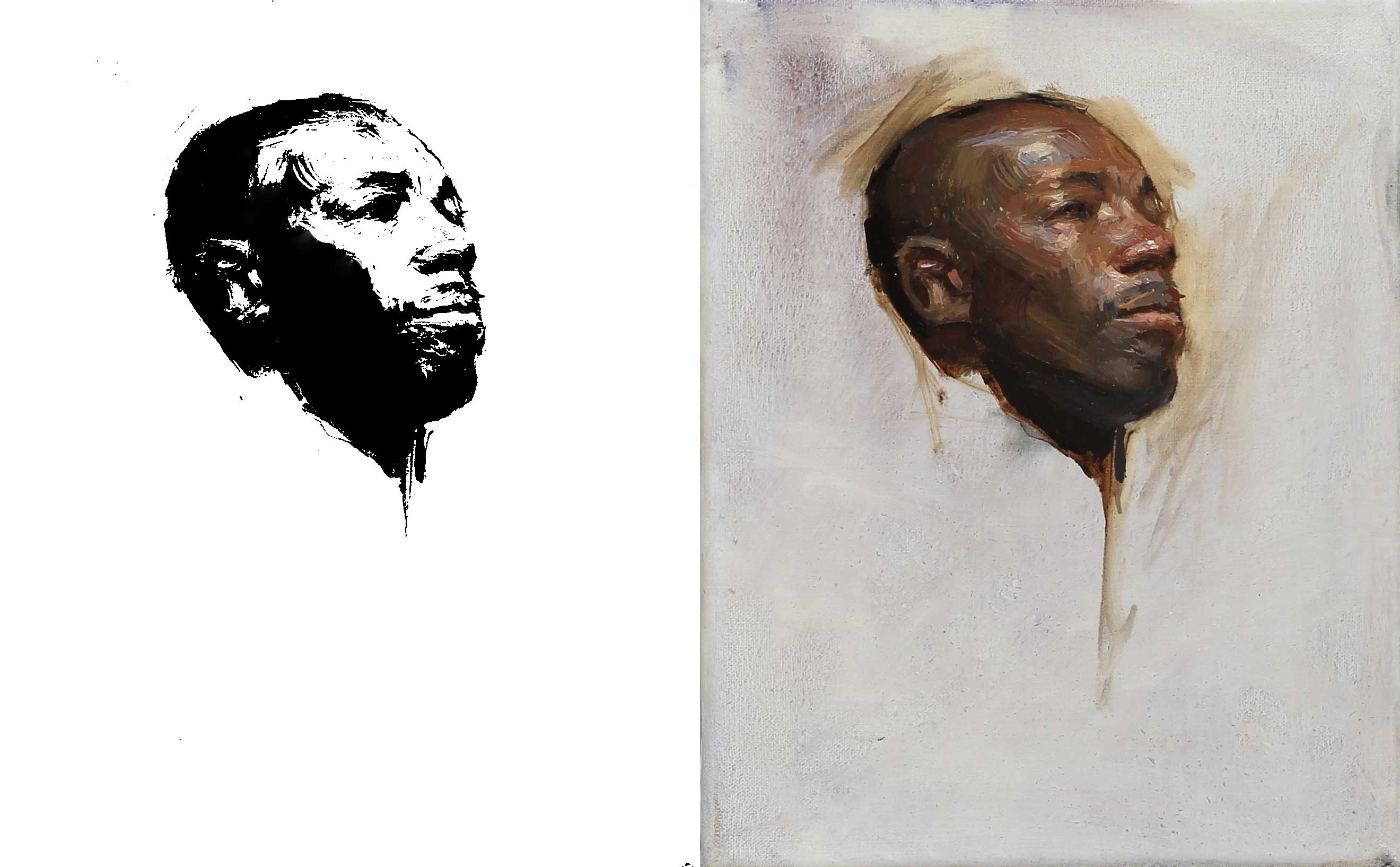

1. The Notan is the fastest way to a likeness. Though it goes by many names, Notan is a black and white pattern (the term refers to a Japanese design) that reveals the light on an object, and therefore the structure of the object. Students who focus on features and details first are doomed to reworking. The Notan allows the student to squint and see an abstract pattern to replicate, which is often easier than drawing something complex like a face. Think of an old newspaper photograph — it’s all black and white, but people are easily recognized.

2. Edges do more work than you think. Most students already know you can use edges to suggest different atmosphere. Some know that you can use edges to describe “what’s in focus.” Few seem to realize that edges play a huge part in describing the quality of the light. Intense lights and the sun have harsh edges. A diffused or dimmer light has softer edges. If your painting of a model under a harsh light has soft edges but the shadow pattern of a spotlight, it will be confusing and never look right. The value range we paint with is almost the same for each painting. Light values don’t describe a spotlight; edges do!

3. Color matching is as easy as 1-2-3, or red-yellow-blue. Matching colors, especially to paint back into a painting, was always a bit stressful to me — until I was struck with what I can say is the only life-changing epiphany I’ve ever had. I knew, like most, what the primaries are and that red and blue make purple, etc. However, I realized that by arranging my palette in a certain way, and shifting my approach to mixing color, I could easily match any color I desired (with opaque direct paint) without the need of a color chart.

A printer uses only three colors—a variation of red, yellow, and blue, with black to mix everything. The problem is that printers use transparent colors, which don’t work terribly well with direct painters. I realized if I arranged all my colors into different value groups of red/yellow/blue, I could behave like a printer:

1. Identify the value (my palette has five value sets of r/y/b)

2. Identify the color family (closest to the red, yellow, or blue)

3. Identify the saturation (if it is less chromatic, more equal amounts of r/y/b)

With this approach to color, I can achieve almost any color, even if I have never tried to mix it or have never used the particular set of pigments I’m working with! The most significant quality of this approach is that white is never used to lighten a color. It is removed from the palette, and in its place off-white red, yellow and blue are pre-mixed. If one wishes to lighten a color slightly, the next value lighter r/y/b is added.

If a color needs to be significantly lighter, a different r/y/b is used from the start. For students struggling with chalky colors, this has been a saving grace. I execute a five-value poster study of my subject before a painting, using grays made from my five r/y/b sets. This poster study tells me which set to use while executing the painting. Voila! No more challenge mixing color! Seeing color, on the other hand, is a whole different issue.

It’s easy to become mystified in the beautiful content and the impeccable execution of a well-done painting. Painting is a wonderful illusion, and as we study to become the next generation of magicians, we must remember there is a very human way to execute them. I still remember the first time a student described my paintings as magical. I didn’t understand because I was so caught up in the science. Everything was empirical—composition, color mixing, drawing, and materials. Everything was calculated and built on the foundation left by current and deceased masters—how could that be magical?

As my skill level grew I was confronted with new challenges, and now seek out work that again piques my interests and presents me with illusions I don’t yet comprehend. Finally, I have come to understand that for me, as well as anyone wanting to learn how to paint, the science is the magic of painting.

Related Article > How to Draw with Charcoal: A Medium With Mystical Gravity

This article was originally published at Realism Today in 2019

***

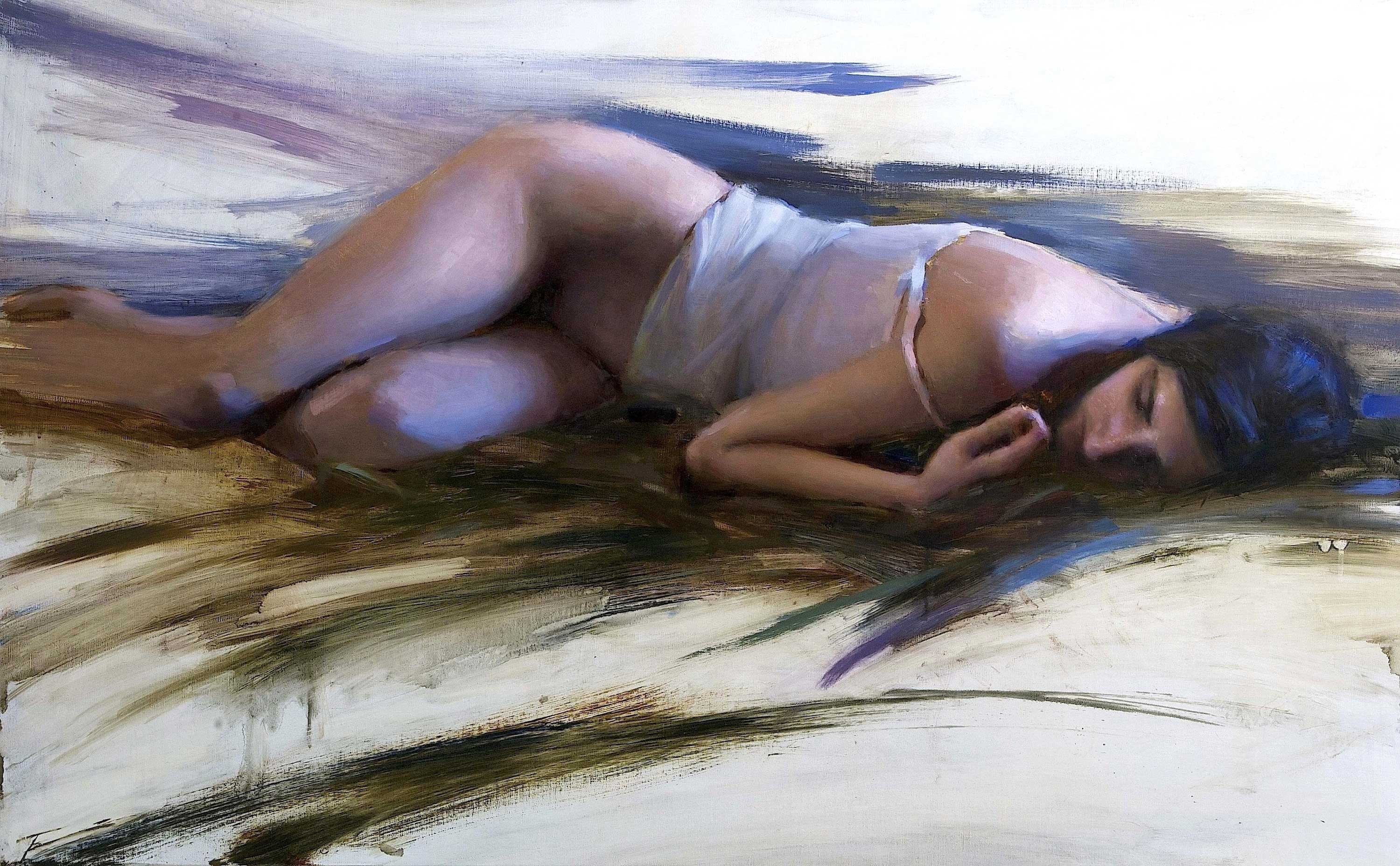

Learn how to paint with Tim Rees! Tim Rees has a workshop on how to paint the figure with oil through PaintTubeTV! Here’s a glimpse at “Modern Figures: Painting Big, Fresh, and Loose” >>>