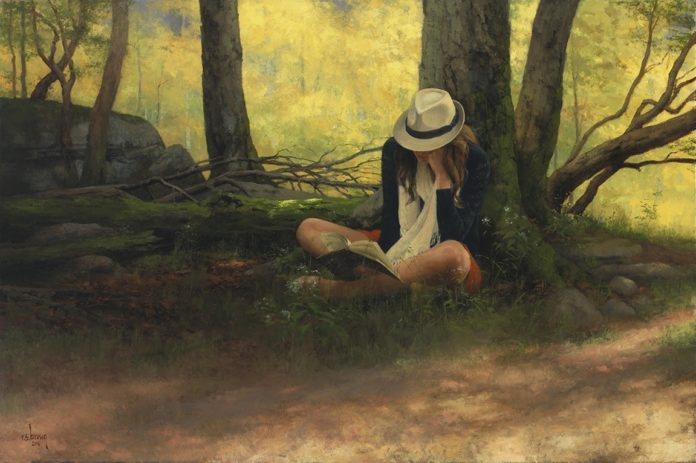

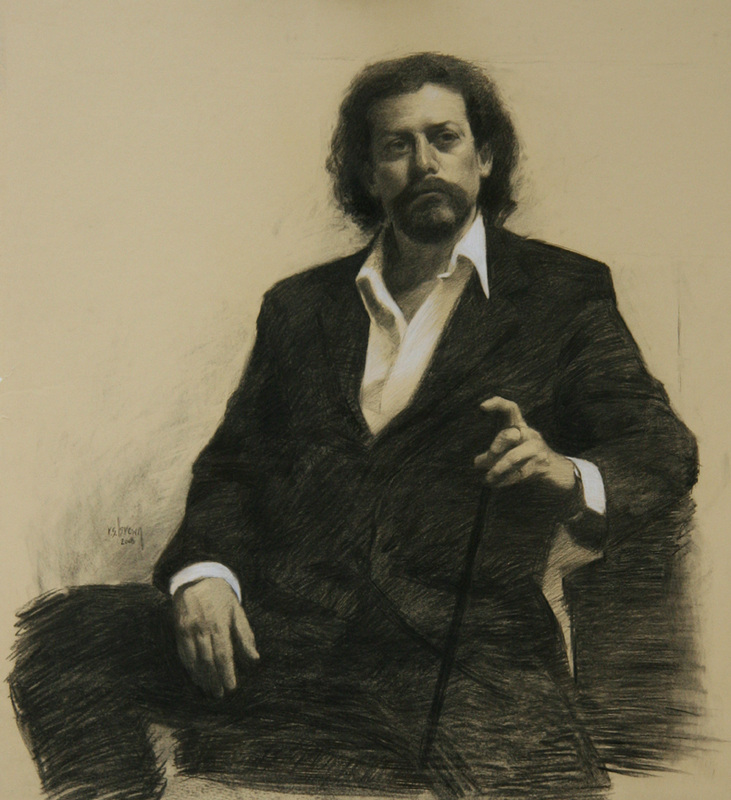

Advice for Artists > Ryan Brown shares advice on how to give yourself the best chance to succeed and become an expert at what you do.

What It Takes to Become a Professional Artist

BY RYAN S. BROWN (RyanSBrown.com)

Every artist begins his or her journey with some passion about art. A passion that drives them to create new things, to bring a vision to reality and dive into a field that fascinates them. It is a passion I wish more people had and would develop. But too often prudence and practical thinking can create fear and apprehension that may lead people away from creative pursuits and into more “responsible” occupations. But is an occupation serving to just occupy your time or is your time serving to occupy your passion? There’s no right answer. Providing a living for yourself and perhaps a family is necessary and noble. But for those considering the possibility that living a creative passion might be something you’d like to do, I can tell you it is possible and I can’t see any other way of living than with and through that passion.

It is my job to daydream, to observe the beauty of my surroundings and love what I observe. It is my job to share that love with others in as elegantly refined and poetic a manner as possible. And I see this as a service-oriented pursuit. Of course my art blooms from my personal vision, but its purpose is specifically to serve the greater need for beauty, truth, and aesthetics for those who may view it. It expands the meaning of my time if I spend that time producing works that help elevate others in mood or thought. Without this particular thought in mind, what I do would seem interminably self-serving and capricious. These two elements of observing beauty and serving others are the governing influences of my career as an artist. There is such joy and fulfillment in this pursuit that I would hope all who might be considering an artistic path for their life might conclude to do so.

So how to do you make or build a career as an artist in order to live out this passion? For me, the first step was to just start creating. One must have the bold abandon to start making things, even if you have no idea what you’re doing. Dive head-first into the dark water even if you think you’ll drown.

But — and this is perhaps the most important part — have the humility to be teachable, always. In order to make a real effort at becoming an artist you must have two things. First, you must be arrogant enough with a naïve abandon to assume you can do it and just go for it. But you must also have enough wisdom to understand that you (as we all do) have limits. There are many things you can learn on your own, but you will make much greater progress toward your goals if you are fair enough with yourself to understand that study is necessary. No one becomes a doctor without medical school. Many people in the arts only exercise the naïve abandon, and skip the step of education. What you have to understand is how inefficient it is to be self-taught. After all, when you are self-taught, you have the most ignorant teacher.

Today’s art education system is a chaotic mess of random bits of information, and often misinformation, that leaves the art student with the unnecessary task of unraveling the complexities of theory, philosophy, and methods to try and decipher a coherent path by which they might make progress toward their goals. When I attended the Florence Academy of Art, I experienced the power of an organized approach to drawing and painting that I had never seen before. I learned more in my first three weeks of academic study than in four-and-a-half years at a university. For many of those having attended an art academy such as this, my story is so common it has become almost cliché.

In the book Peak: Secrets from the New Science of Expertise, co-authors Anders Ericsson and Robert Pool discuss in-depth the basic realities of human development. It expands the concept of the 10,000 hour rule to include three key factors. One is time spent in practice, of course. The second factor is that this time in practice is spent in a well-designed progressional system meant to build skill or knowledge from simple to more complex. And the third is to have that organized practice watched over and criticized by one who has mastered the elements of the given field of study.

Much of what I hear given as advice in the art world ends at just “practice.” “Draw, draw, draw” is a quote by Degas I often hear. “Put more mileage on your brush” is another phrase I often hear. But without an organized or deliberate approach to practice, one is more likely to merely become increasingly efficient at doing something mediocre rather than developing greater skill and a deeper knowledge. And having consistent criticism from a proven source serves to bring awareness to elements of knowledge one is unlikely to discover on their own. We are all unaware of what we are unaware of.

The acquisition of knowledge and development of skill should come as early as possible in an artist’s career. But it is never too late. If you are true to yourself and your vision, you won’t let anything stand in your way of development.

I hope for those who read this that this advice comes across as more of a call to action. I am not trying to preach, but to be a cheerleader offering encouragement that you can do this. YOU CAN DO THIS!! Just give yourself the best chance to succeed and become an expert at what you do.

So now let’s imagine you’ve developed this skill and you’re beginning to make well-crafted, well-thought-out work. Now what? How do you afford to keep doing it? If you can’t answer this, it just turns into a really expensive hobby. There are two main paths I have experienced in my career (which is an oversimplification for the sake of this article). One path is driven by money and one is driven by art.

It is important to decide for yourself what your priorities are and be true to them. For many, the need to make a living is real and must be considered. But, if you’re not careful, it can adversely direct your efforts and control what you make. Inevitably, at some point you will create one or two works that everyone seems to love. And the galleries seeing this positive response to a particular subject matter, size, composition, or color harmony, will ask for more of the same. And you’ll give it to them, because selling feels awesome, and getting a positive response to your work feels even better.

The danger is that this can unwittingly become your calling card, your style, your brand. Through no deliberate attempt or designed choice, you can brand yourself and find yourself regurgitating the same work for decades.

For many, they feel there is no downside to this. The benefits are that you establish a brand early and develop a growing clientele that wants the brand of art you make. It’s easier to sell a known commodity. Galleries like a clear brand and collectors like known brands. It is easier to sell and easier to attach a prescribed value to such work and such artists.

But on a personal level, you have to ask yourself if creating such similar work for so long will be satisfying to you. This is where your personal priorities must be clear to you. The joy of selling, the joy of becoming better known, and the joy of making a good living as an artist may be exactly what you want for yourself. And if you know that, and choose it deliberately, then you’ve won. The direction of branding, and marketing that brand is what I would categorize as a more money-driven priority. Perhaps that may read as negative, but it is not. I do not subscribe to the idea that money can’t buy happiness. Money buys time and freedom, which can lead to happiness. And a lot of really great art is made by artists with these priorities. Having prioritized financial success does not disqualify anyone from creating lasting works of great beauty.

The direction that is more art driven concerns itself little with style or specific branding. This path tends to consider each piece individually as a stand-alone work of art. The artist who prioritizes the art is more exclusively concerned with the craft, aesthetic, and execution of each piece, more often than not to the detriment of the marketing of his/her work. The development, understanding, and refining of the knowledge, craft, and expertise that goes into their art is of far greater concern to these artists than the marketing aspect. There is a greater satisfaction in the creation and execution portion of the process than in the sales and marketing. A lot of great work is done with this priority, and much financial success can be achieved in this way as well. But for artists such as these, the lack of marketing always holds the potential reality of lingering anonymity.

Both sets of priorities are valid and neither one is above the other. I believe much of what leads artists toward one or the other is based on their individual temperament and interests. The point I’m trying to make is that it is best when an artist can make these choices deliberately and confidently, without apology. It requires a certain level of maturity in vision to have a serious sit-down with yourself and define your priorities. With a clear definition of priorities in place, it then takes a good amount of discipline and effort to create and follow a plan toward accomplishing your vision. It takes an equal amount of determined focus to stay aimed in your desired direction. Which leads me to my last bit of advice.

It is very easy to become distracted as an artist. There is so much potential, so many possibilities. As creative beings, we love to explore, experiment, and discover new things. We want to try out different techniques, new approaches, new subject matter, etc. And all of these things are good. Follow your heart. Just be careful not to follow your fickle heart. You can very easily stretch yourself too thin by trying to do everything, enter every competition, apply to every exhibition, and join every organization. You might do this in the beginning to get some attention or recognition. It’s not a bad idea. It’s not the only way, but it certainly has worked for some. But these exhibitions and competitions can be deceiving. They can lead you to make work you otherwise wouldn’t make, guessing at what this judge or that gallery wants to see. And if you win or lose it can make you believe that either was earned.

Getting in a show or winning an award can feel great, and it can be great in terms of getting you recognition for your work. It can also lead you to a cycle of creating work after work that is designed solely around trying to win that next award or please the next judge. And not winning, getting rejected from shows can lead to crushing feelings of inadequacy. You must find a way to love what you do regardless. You must get direct and honest critical reviews along the way from trusted peers. And you must always push forward and improve, regardless of awards, exhibitions or gallery response. This is easier said than done. The distractions are many and your ability to remain focused will be unquestionably linked to the clarity of your priorities and singularity of vision.

A Final Word

I feel forever fortunate that I found the Florence Academy of Art and for the education I received there. The experience of opening my eyes, clearing the fog, and developing an awareness of how to see and interpret the world around me was life changing. It gave me the tools to construct my own visions. This transformative experience made me want to share this education with as many people as I could.

It is with this in mind that I established the Masters Academy of Art in Utah. Our objective at the academy is to understand the individual needs and goals of each student to help them find a more efficient and economical way to acquire the skills they need to bring their personal visions into existence, with as great of expertise as possible. This is important because no matter how great or clear your vision is, the depth to which you can execute that vision visually to others will always be relative to the skill with which you are capable of executing it.

This article was originally published in 2019

Learn from Ryan Brown, a Realism Today Advisory Board member, with “Painting Classical Portraits,” his premium art video from Streamline Publishing (preview below).