Christopher Benson on danger of confusing the level of our craft with the quality of our art:

Art Versus Methodology

BY CHRISTOPHER BENSON

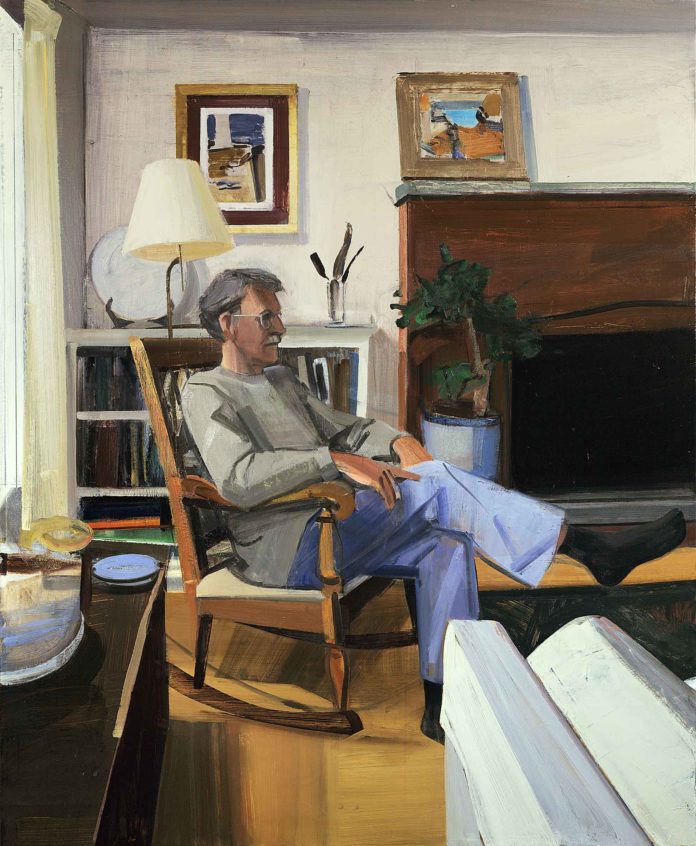

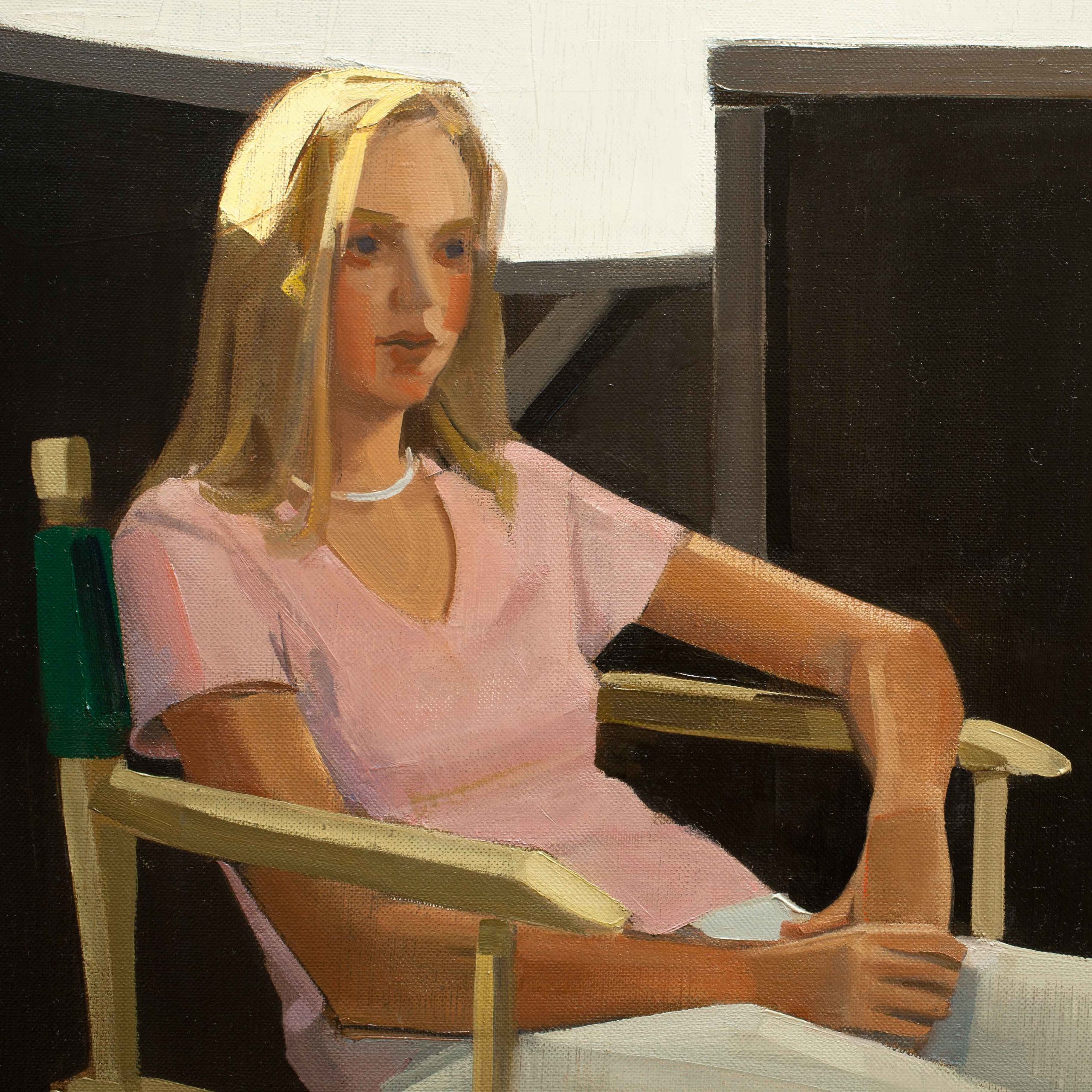

I began making representational paintings as a boy in 1970. Since then, I’ve painted hundreds of pictures, always basing my aspirations on a careful study of the long legacy of painting that preceded me. Alongside that affection for the art of the past, I love modern art too, and have tried to look clearly at the world today and represent it in some way that integrates the best ideals of my time with the older traditions that are so meaningful to me.

As an art student in a late Modernist period that rejected traditional representation altogether, this approach set me on a challenging path. During the Postmodern 1980s and 1990s that hostility gradually subsided, but a residual avant-gardism in the mainstream art world continues to disdain any earnest affection for art history in favor of a distanced and ironic appropriation that sneers at the sources it mines.

Happily, a growing number of painters are today re-embracing art history as a living thing, rather than as some battlefield carcass into which the latest banner of innovation should be staked. We see this in the proliferation of new landscape and scene painters, as well as in the works of those aligned with the figurative “Atelier” movement.

I welcome the shift—at least insofar as it feels good to see so many younger painters taking up representation with such ease and gusto. That said, I feel some ambivalence at the prospect of a reactionary Neo-Neo Classicism that would toss much of the worthy progeny of Modernism and Postmodernism out the window.

Before the Impressionists, innovations evolved from past precedents rather than by annihilating them, and artistic movements were more organic than manufactured. Since then, the cycles have seemed always to begin with somebody announcing a death. The authors of such proclamations invariably strike me as being either unimaginative or self-interested.

I for one yearn for an anti-movement—one not limited by the proscriptions of some exclusively authoritative orthodoxy. Far from being dead, the whole of our aesthetic heritage, including all the diverse arts of the twentieth century, offers fertile ground for reinterpretation if we can only think of how to sow it.

All of which brings me to craft. I am speaking here about painting, and painting is a craft before it can be an art. One must learn how to draw and paint things well in order to represent them persuasively to others. Interestingly, this is also true for abstraction, as the greatest abstractionists were often grounded in representational training. Think of the pre-modern near-abstractions of late Turner or late Goya, or of Modernist titans like Picasso, Mondrian and deKooning—all skilled representational artists before turning to their more expressive interpretations.

However constituted, the painter’s skills are hard-won, and their attainment is one of the great personal satisfactions we can know. There is a danger though, when falling in love with a craft, in confusing its cleverness or difficulty with the source of art itself. This is the one fatal flaw I see in some of the new representational painting—that it is besotted with technique, with no corresponding understanding of the higher artistry that skill can lead to, but which is not solely a manifestation of skill.

Perverse as it may feel to the master technician, the most flawless execution does not always translate into the greatest work of art. For example, the near magical technical accomplishments of a Holbein, Bronzino or Ingres (all great masters of their kind) inspire tremendous admiration and even awe, but none of those painters has historically enjoyed quite the widespread appeal of a Rembrandt, Turner, Monet or Van Gogh. Why is this so? My sense is that as dazzling as such displays of technical mastery can be, they showcase their virtuosity at the cost of a more relatable humanity.

The English Arts and Craft architect J. D. Sedding once said, “There is hope in honest error, none in the icy perfection of the mere stylist.” Perfection, for our human lot, is a fantasy which, when we encounter something close to it, can make us feel a bit uncomfortable. Who among us (save the pathological narcissist) can honestly claim perfection? To me, the greatest art is that which points to the sublime while admitting the human frailty that denies its attainment. Flawlessly executed craft is a kind of perfection, but one that tells only a half-truth. Great art, on the other hand, tells the whole story.

Craft is certainly a first step to artistry but, paradoxically, one that must be transcended in order for art to come to life. (It should be understood too that according to that same reasoning, there is the potential for great artistry in every craft.) A transformation occurs when a maker so masters his or her tools that the reliable steps of their formulae can be challenged to re-assert the fallible humanity that defines us. Skill does not go away in that process, but is reduced, like a complex soup, to its essence. We don’t any longer see the onions, carrots or bits of meat and bone, but we can savor their lingering presence in the whole of the magnificent broth to which they have contributed.

The importance of reasserting a more realistic and relatable humanity into the lofty aesthetics and methodologies of the French Academy and Salon was the vital principle advanced by the first Modernists in their revolt against those institutions 150 years ago. All the great avant-garde Modern art that followed built on that principle. Ironically, the descendants of that same avant-garde have managed in my lifetime to establish an intellectualized institutional order rivaling the aloofness of the Academy it originally overthrew. This is the chronic problem with the revolutionary mindset—that it deposes one tyrant only to build a foundation for the next. A certain poetic justice attends this assault on the new academy by the reinvigorated champions of the old one, but I would frankly prefer not to live or work under either of those despots.

Learn more about Christopher Benson at: www.bensonstudio.com