Your ability to “experiment” and create is based on your solid understanding of the science of painting. The more experience you have working out the science, the braver you become with experimenting.

The Authorship of Painting

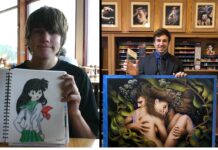

by C.W. Mundy

Artists, art aficionados, and art collectors could greatly benefit from an understanding of the technical aspects of painting—what I call the “foundational truths.” For the artist, an understanding of these truths builds the foundation or structure for a great painting. For the art collector, this understanding helps clarify why a painting is considered “good” or “beautiful,” and gives him or her an ability to look at, appreciate, and articulate art, rather than shy away from discussion through lack of confidence in their art knowledge.

Science

A proper definition for painting starts with the understanding and clarification that painting is a science. It’s based on historical, researched facts. Red is the complementary color of green. Blue is the complementary color of orange, yellow is the complementary color of purple, and so on. There are also innumerable scientific elements of design and composition, such as the golden mean, the Fibonacci sequence, perspective, and vanishing point. I could go on and on, but I think we would all agree: “Painting has its disciplines.”

I have chosen to narrow the disciplines down to these, the Seven Foundational Truths: (1) squinting to “simplify,” (2) design, (3) drawing, (4) value, (5) color, (6) edges, and (7) paint manipulation—with variety and unity in their correct proportions in each discipline.

The art of painting is placed high on the list of creative sciences, along with drawing, sculpture, music, dance, theatre, cinema, and sports. Having been an athlete, and a professional musician, as well as an artist, I understand that one must learn, study, and practice (and practice and practice) the basic foundations and technical aspects of his or her craft—over and over again!

Experimentation / Creativity

Having begun to understand the basic foundational truths and continuing daily to learn and grow in these disciplines, an artist can now add his own voice. The artist’s voice will evolve naturally by searching and working through the seven foundational truths. You need not force your voice—it’s who you are, based on all of your life experiences.

This is the time to experiment and try new ideas. I’ve often said, “I’m a child trapped in an adult body.” Children don’t usually get bored and can continually re-invent themselves and their focus, often on the spot! It’s like being the explorers Lewis and Clark—always on an expedition of adventure and discovery. Quang Ho, an artist friend of mine, has been quoted as saying about me, “C.W. seems to be constantly searching and challenging himself with a fearless attitude. You can see it in the paint application,” Quang said, “which comes across in the expressive quality of his paintings.”

I’ve been known to tell my students, “You’ll never know how far left is or how far right is until you hang out on a limb.” In other words, try new things in all directions, such as the expressionistic and the realistic. This is how you find your “sweet spot,” or where you are most comfortable. Your sweet spot will also continually change as you grow and press forward in the issues of experimentation. On the downside, experimentation will always bring in a host of failures, but on the upside, the benefits of greater study and experience will bring in exciting results, maturity, and higher level of authorship.

Experimental Challenges

With all the seven foundational truths—squinting, drawing, design, value, color, edges, paint manipulation—there can be a multitude of challenges to explore.

For example, it has often proven beneficial and productive in the history of art to paint a series of paintings of the identical subject or similar subject, but with different conditions or styles, or with different visual ideas. Monet is a great example of this approach. When he painted his “Poplar,” “Haystack,” “Rouen Cathedral,” and “Lily pond” series, Monet took on the task of exploring the possibilities—the effects of light and atmosphere, color, times of day and weather changes, palette color, paint manipulation, and so on. The search produced some of his greatest work. It’s often about the process and learning, more than the completion. But the completion can also be very rewarding!

With my series of beach paintings this past winter while in Florida, my goal was to try many methods of “paint manipulation” of similar subject matter, and not necessarily focus so much on the subject matter. I asked myself: “What can I get away with?” “How much can I push the envelope?”

Several years ago, I did a series of 15 still life paintings, all the same size—9×12—but with entirely different subject matter in each one. I explored the “golden section” by moving it to a different area of the canvas, just to see which design and composition ideas worked. (E.g., this golden section rotated from the top left (what I call “station #1” in painting #1), to the top right (station #2/painting #2), to the bottom left (station #3/painting #3) to the bottom right (station #4/painting #4) and so forth.) The process really schooled me, was interesting, exciting, and successful. A recent series of still lifes explored a similar theme, but used the same objects. I explored color changes and color harmonies, and design and composition changes.

My “Toy” series was done based on a theme or narrative for each painting. I pulled my toys off the shelf and then set them up in scenes to create a “storyline,” similar to a child pulling toys out of his toy box and creating an imaginary story. I veered away from impressionism to paint all of these paintings in a realistic manner “from life” without the use of photography. I’m not against photography as a starting point for a painting, but part of the purpose here was to work on and improve my drawing skills.

Another experiment, in years past, involved an “unorthodox” method of paint manipulation—using Kleenex to scumble and manipulate the paint. Another technique I have investigated is “marbleizing the paint.” I load up the paintbrush with “pot color” (mixed mother color) on my palette, then dip it into the pure chroma of the tube colors on the sides of the palette, then without mixing, directly apply the paint to the canvas and mix it there. (In many cases, I’ve noticed that artists’ palettes are more interesting and exciting than their paintings. Sad but true!)

Reinventing yourself will always, metaphorically speaking, break off the dead branches and sprout new shoots.

Mother color is the assessed color and value of large shapes or passages, i.e. sky, mountains, and foreground. There would be a mother color/value of sky, a mother color/value for the mountains, and a mother color/value for the foreground. Using mother color pots of paint expedites the process in painting and keeps you from having to re-mix large masses of paint. Having to continually mix colors while trying to paint can take you “out of the zone” from the continuity of the creative right side of the brain to the analytical left side of the brain.

C.W. Mundy, “Brass Teapot, Pomegranates, Flow Blue Pitcher and Pear,” 2011 9 x 12 inches, oil on linen, painted from life, Collection the Artist

The Creative Process

The creative possibilities in painting are endless. Don’t be a copycat artist! The art market is always looking for something new. As fellow artist Carolyn Anderson said, “I’ve seen that before—show me something different!”

Your ability to “experiment” and create is based on your solid understanding of the science of painting. The more experience you have working out the science, the braver you become with experimenting. Express your own attitude and voice! It will naturally evolve with a solid work ethic. I tell my students: “Mileage!” This was one of my great lessons, among many, that I learned while studying under the tutelage of Donald “Putt” Putman.

The science of painting is the starting point, after which you need to be willing to step out and experiment and develop your voice and personality. Learn your craft as a painter, and then personalize it—as an artist! That’s the highest level of execution. You’re only as strong as your weakest link.

Helpful Links:

- Visit C.W. Mundy’s website

- Make your artwork memorable and eye-catching with C.W.’s expert advice on arranging your subjects and ensuring each piece’s overall harmony in the workshop “7 Foundational Truths.”

- Learn C.W. Mundy’s breakthrough upside-down painting method which is proven to trick your brain and silence your inner critic in the workshop “Painting with Freedom.”

Become a Realism Today Ambassador for the chance to see your work featured in our newsletter, on our social media, and on this site.