Civil War Art > There is a lot of superb contemporary realism being made these days; this article by Allison Malafronte shines light on a gifted individual:

The painter WILLIAM BLAKE (b. 1991) is, in his own words, “obsessed” with America’s Civil War and has made a life, and a living, re-enacting and memorializing its events. Modeling himself after Winslow Homer and Edwin Forbes — both of whom documented the war as artist-correspondents — Blake travels to battle re-enactments around the country, draws and paints on site, and returns to his Philadelphia studio to reconstruct his observations on a larger scale.

Having participated in more than 40 re-enactments to date, Blake takes a fully immersive approach by camping on battlefields, constructing period clothing, and retracing Homer’s footsteps as closely as possible. Based on his research, Blake even set up the re-enactment of a doctor who demonstrated the techniques of embalming fallen soldiers. He has also organized and painted croquet matches, and he painted a trench scene based on Homer’s “Prisoners from the Front.”

In his self-portrait “Antique Disposition” (above), Blake compares himself to a player on a different kind of stage. This painting is inspired by John Singer Sargent’s 1890 portrait of Edwin Booth, 19th-century America’s greatest Shakespearean actor, who was particularly admired for his performances as Hamlet. It was his younger brother, John Wilkes Booth, who assassinated President Abraham Lincoln in Washington in 1865. Deeply troubled by the crime, Edwin went on to perform Hamlet more times than any actor before him, with the murder scenes taking on new meaning.

For Blake, the significance of Booth’s personal life and also his profession has great relevance to his own work as a re-enactor. He is especially moved by Booth’s handling of the play-within-a-play, when Hamlet provokes his father’s murderer, Claudius, by re-enacting the scene of that death.

“I am fascinated by Edwin Booth, as well as by artists of the past who painted other famous actors,” Blake shares. “With all of these players and their stories, a sense of history is created. In the same way, when we are on battlefields as re-enactors, we are creating history again.” In “Antique Disposition,” Blake the artist-actor — dressed as a Confederate cavalier — takes his place on a shallow stage. “Because re-enactment is recursive and resurrective in nature, I am also connecting this concept to art forms often thought to be dead: craft, theater, and painting.”

Additional Civil War Art by William Blake:

On “Incredulity”

“Caravaggio painted ‘The Incredulity of St. Thomas’ with Christ looking down as he pilots Thomas’s hand to his side, not looking at Thomas or the others but to his wound,” said Blake. “He seems interested in the proof of his embodiment. He wants to know that this is real. He too, questions his body, his life, and death.

“Reenactment is a material culture where the feel of authentic wool is transformative. The closer you can recreate the ‘kit’ of the authentic soldier the closer you are to that past. In the pursuit of touching the past there are questions – Is this real? Did this happen? Is this me? Is this us? The gesture of piloting a finger into the side are these repetitive questions.”

On “Amputation”

“During a battle reenactment at the Daniel Lady Farm in Gettysburg, I helped carry a soldier from the field to the hospital,” said Blake. “This painting depicts that soldier as his leg is amputated. Clara Barton checks his pulse as the surgeons saw through the bone. She loses his pulse and eventually pronounces the man dead.

“The man, a true amputee, was fitted with a slip-on pig bone wrapped in pig flesh to better present the surgery.”

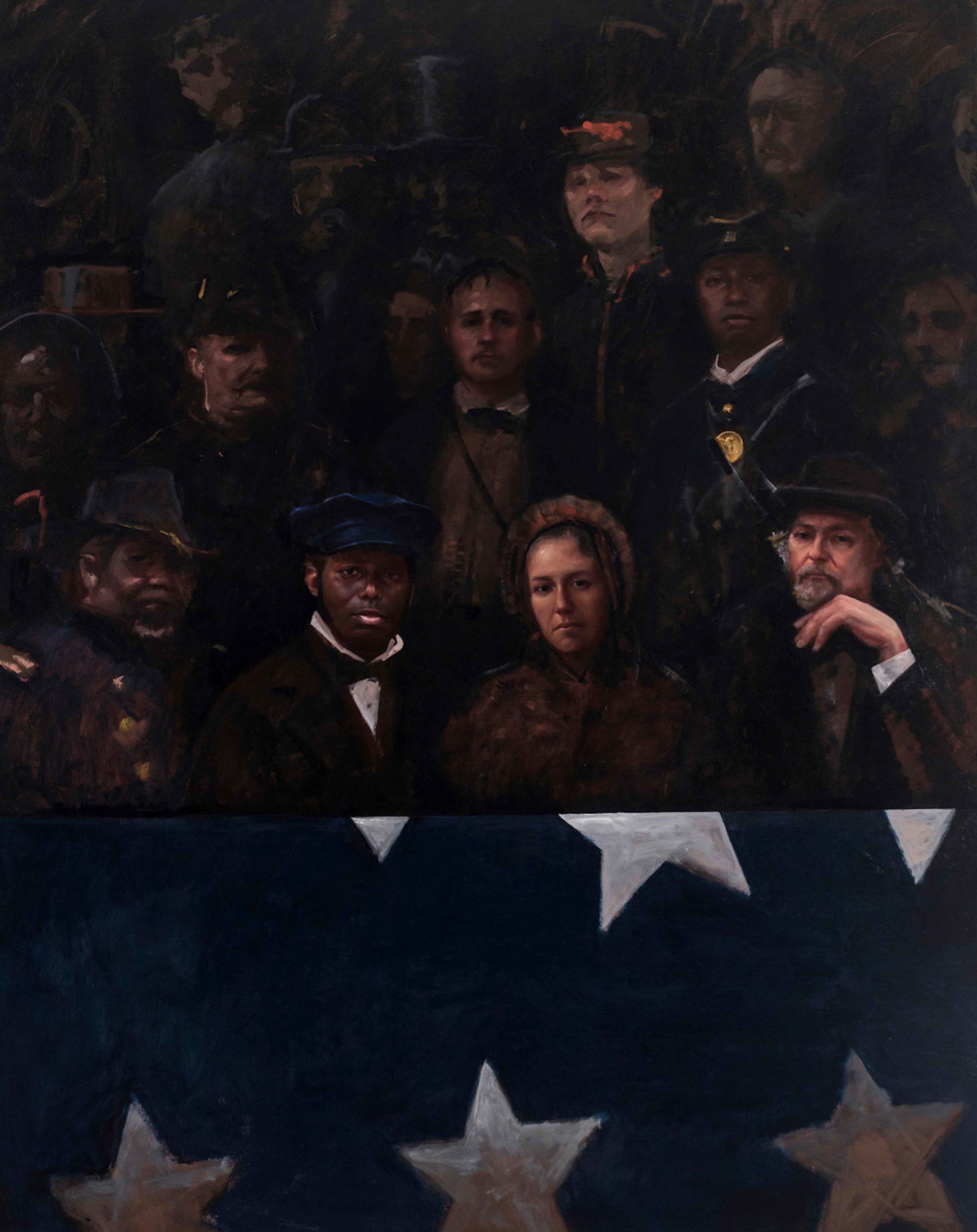

On “Grand Review”

“Historically, the Grand Review of the Armies was a victory parade held in Washington D.C. that lasted two days at the end of May, 1865,” said Blake. “The parade contained the largest standing army in the world at the time. However, it did not contain any of the 180,000 United States Colored Troops (USCT) within the Army. One hundred and fifty years later, this parade was reenacted down Pennsylvania Avenue with the USCT leading the procession.

“From Goya to Manet, and to Magritte, the trope of a frontal facing balcony painting interests me as a space for the past to view the now and vice versa. The life-size figures engaging eye contact with the viewer, creating a moment in which the audience is both the viewer and the reviewed.

“Due to the inability of the past to completely articulate itself, reenactors are engaging in a contested field of investment. They gesture with respect and the desire to educate, humble, and play. This is why it is important for me to use genuine reenactors who understand this relationship as models. The finished painting encourages a review of history and aids in its continuous revision.”

William Blake is self-represented. For details, visit williamblakeart.com or @william_blake_studio.

Portions of this article were originally published in Fine Art Connoisseur magazine (March/April 2019).

From our sponsors:

Streamline Art Video presents “Rose Frantzen: Portraits in Conversation”

Video Length: 12 Hours, 50 Minutes

Preview this and learn more at PaintTube.tv.