Contemporary Realism > “Whether we are called kitsch, grotesque, dark, or low brow, narrative storytellers are painters searching for sentimentality…an honorable pursuit.”

BY JEREMY CANIGLIA

People always ask me why a majority of my work centers on birth, love and death. I suppose the answer is that grappling with these themes helps me to understand the impermanence of life on this planet. Creative expression through narrative storytelling can be a powerful platform for fighting oppression and breaking the silence of indifference.

In the midst of a pandemic that reminds us of our mortality and the need for empathy, it is abundantly clear that, while our world contains beauty, that beauty is subject to pain, suffering, and cruelty. To ignore that narrative thread, to brush aside climate change, wars, genocide, poverty, famine, and disease, and to act as if art is an escapist medium whose sole purpose is to depict platonic ideals without reference to our fraught world, feeds indifference and encourages ingratiation with the ignorant.

Nonetheless, few painters are willing to go against the grain and depict humanity at its most grotesque. They fear rejection, or that galleries and collectors obsessed with the cult of the beautiful will only want to showcase “safe” paintings that they hope will not visually challenge a complacent audience. This attitude relegates masterpieces portraying the human condition in its brutal essence to museums and old churches.

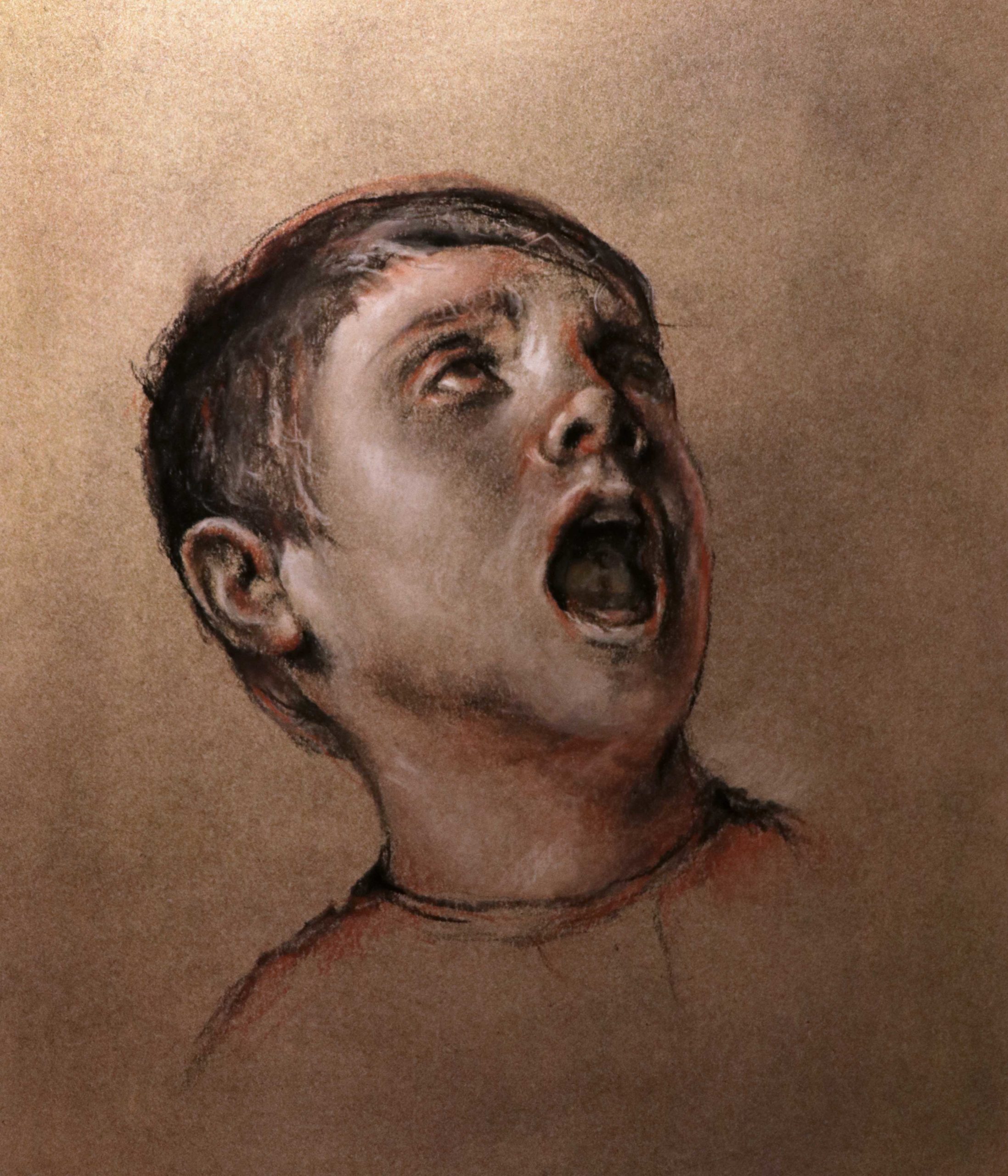

It is a mistake, however, to assume that the viewing public is complacent. Caravaggio, Giuseppe de Ribera, Artemisia Gentileschi, Fransisco Goya, and Käthe Kollwitz, among others, were willing to refrain from “prettifying” or embellishing the human condition and instead exposed its darkest realities. The timelessness of their work can be measured in increasing demand for it, both in collections and as seen in viewership numbers at museum shows. That timelessness is anchored by the simple fact that beauty is not the only archetype of relevance to painting, nor even the most important. Others, such as pathos and ethos, imbue art with greater meaning, a fact that the aforementioned artists understood explicitly and that the public does implicitly.

“If art is not as brutal as it is beautiful, then it does not explore the truth of the human condition.” ~Jennifer Scott, The Sackler Director, Dulwich Picture Gallery, London

Archetypes referencing despair, sorrow, and death are more than simply grotesque. Rather, they force a light upon the deep shadows of our complicated world, forcing us to confront fear of and complacency towards the unseen tragedies occurring every day. The future depends on our action to right wrongs sprung from apathy and greed. Art can play an essential role in combating those vices, but if it is beautiful without simultaneously being brutal, it furthers the complacency that leads society away from the warnings of scientists and experts and towards vacuous promises of a poorly remembered past.

We must recognize that painting is not all beauty and life is not always beautiful. Having said that, though, we must also recognize that beauty need not be found at some vantage far removed from the harsh realities of life. Rather, seeing the beauty in the struggles we face and looking for light in the darkness that can surround us helps us create an understanding of who we are and what we are about. This exercise gets to the heart of the central questions of the painter’s profession: Why does an artist create? Can we truly create a painting if we have nothing to say with it? Are we capable of giving ourselves to something even if we do not fully understand it?

Answering these questions truthfully brings us to timeless archetypes, at once grotesque and beautiful. When I was in Pompeii and Naples, Italy in 2017, I had the opportunity to study early Greek and Roman frescoes and mosaic pieces created in the dramatic skiāgraphiā style, which uses the illusion of both shadow and light to create an early type of chiaroscuro effect dating to the 5th century, BCE. The technique was developed by the painter Apollodorus and noted by early historians Plutarch and Pliny the Elder.

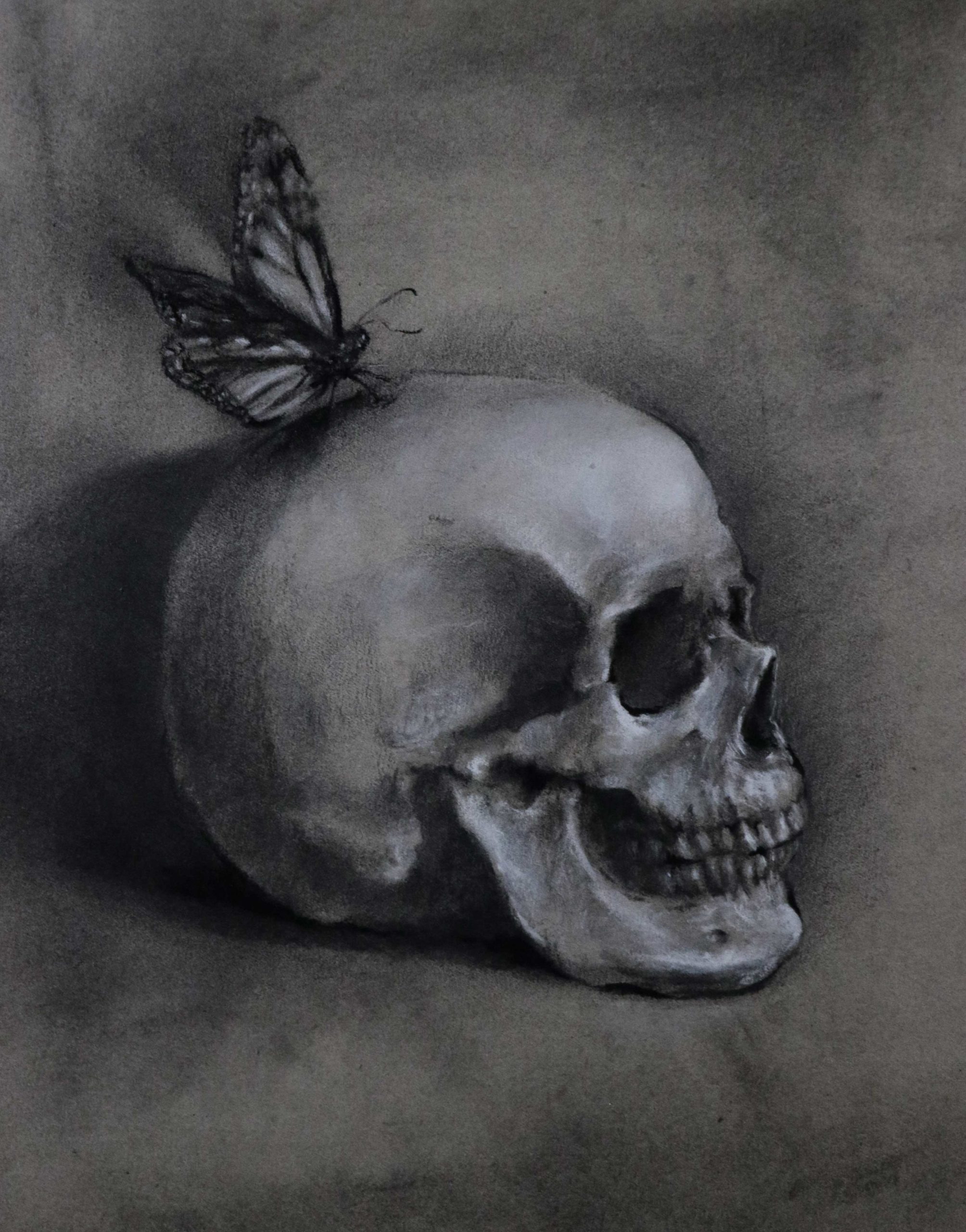

One ancient mosaic that stood out was “The Leveler,” dated ca. 30 BCE, which presents the Hellenistic story of death as the great leveler who cancels out all differences of wealth and class. A skull is portrayed as the weight on the level’s plumb line, below which is a butterfly representing the soul and a wheel representing fortune. The piece is a great juxtaposition of empathy and apathy and demonstrates how death is the great equalizer in our world.

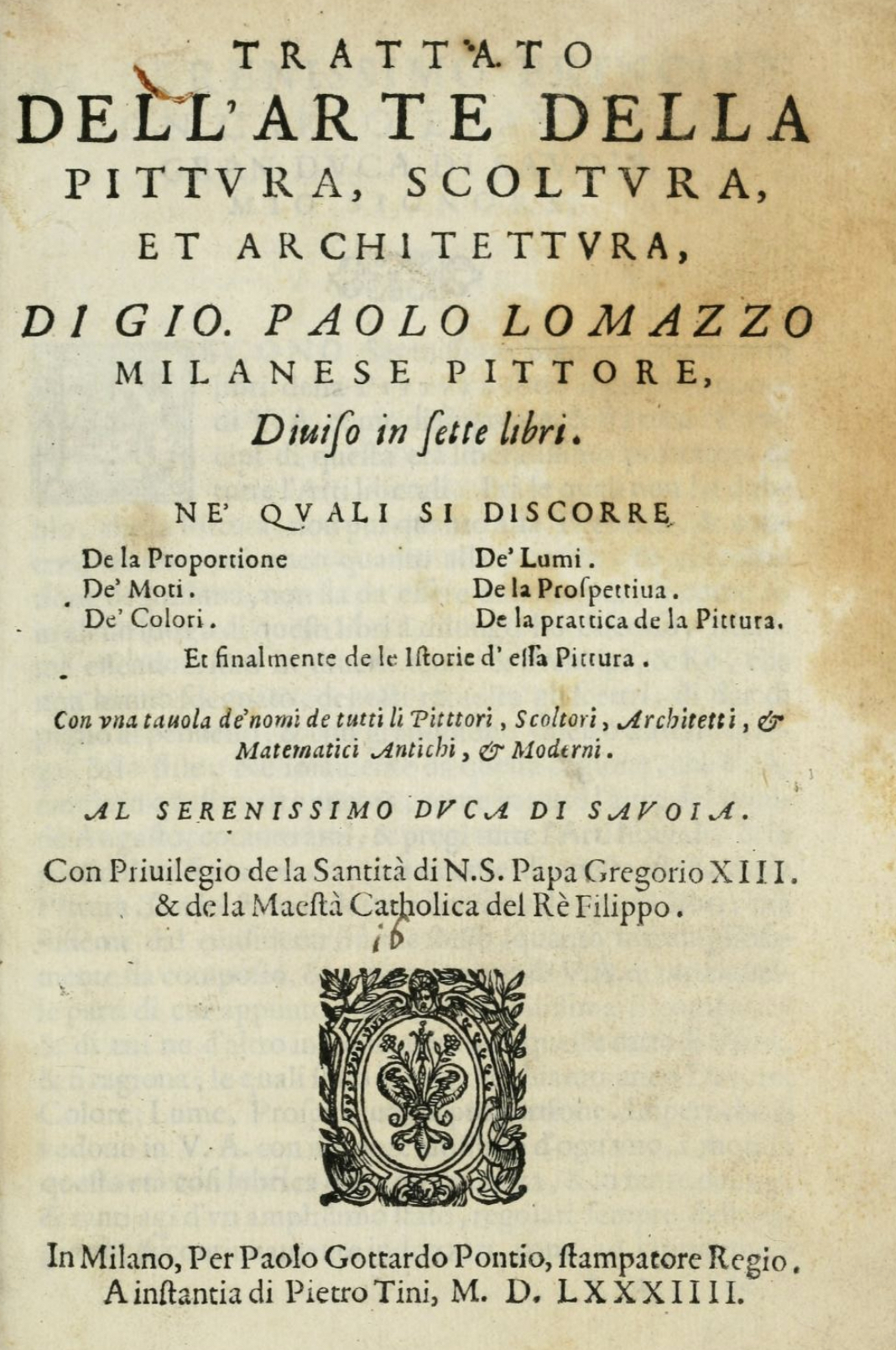

About 1500 years later, the same archetypes remained prominent in the artistic discourse. Giovanni Paolo Lomazzo wrote the Treatise on Painting, Sculpture, and Architecture (Trattato dell’Arte della Pittura, Scoltura, et Architettura) in Milan, in 1585. The Trattato was the largest and most comprehensive treatise on art published in the 16th century. It was divided into seven books, whose themes are Proportion, Motion, Colour, Light, Perspective, Practice, and History.

In Chapter 48 of the sixth book Lomazzo talks about The Composition of the Grotesques. Lomazzo states: “I am for my part convinced that there is no more convenient way to draw and express a concept than by means of grotesque art. Only in grotesque art it is allowed to use so many forms, such as sacrificial gifts, trophies, musical instruments, forms in relief, and also concave, convex, twisted and hanging shapes. Then there are all kinds of animals, foliage, trees, figures, storms, lightning, oil lamps, lighted candles, fantasies, monsters …

“In short, everything one can think or imagine. The composition of grotesques should always in the first place present a natural truthfulness… In my opinion it is harder to impose order on something disorderly, than to follow something which is already ordered

in itself, since it already possesses order, and demands nothing else than to be recognized as such.” ~Giovanni Paolo Lomazzo – Trattato dell’Arte della Pittura, Scultura, et Architettura, Book 6, Ch. 48, 1685. tr. Liliana Jansen-Bella and Thomas Crombez.

This attitude can be identified across Michelangelo Merisi da Caravaggio’s work. It should be noted Caravaggio (1571-1610) would have been 14 years old at the time the Trattato was published, but would have learned about it from his Milanese instructor Simone Peterzano.

Caravaggio’s Death of the Virgin is a perfect example. Causing scandal on account of its harshness when it was first unveiled in a chapel of the Carmelite church of Santa Maria della Scala in Rome, the painting starkly contrasts classicism with naturalism. Rejecting the pretty idealism of Mannerists and Carracci’s re-packaged Renaissance art, Caravaggio used ordinary working people as his models, mixing gritty chiaroscuro and tenebrism.

Gazing at the painting, viewers can feel the weight of death and mourning. Light and shadow play off of one another amongst the central figures who surround the Virgin. Mary’s flesh is vivid and lifeless, dirty feet indicating decay. There is no ascension, only sorrow.

Repetition of Caravaggio’s compositional structure underscores its timelessness. Käthe Kollwitz (1867-1945) used her work to educate and fight against war, famine and poverty. She would borrow from Caravaggio’s composition in her etching depicting the farewell and death of Karl Leibknecht, who was killed in an uprising in Berlin. As in Caravaggio’s work, brutality is not sidelined to make way for the beautiful. It takes center stage and gives Kollwitz’ etching its emotional impact.

Unfortunately, the philosophical lineage that Giovanni Paulo Lamazzo expressed in 1585 consists of masters who were seen as outcasts and troublemakers in their times. When, in the 1980s, I realized that I was a graphic storyteller, I came to love the skillful, dramatic renderings of Caravaggio, de Ribera, Goya, and Kollwitz. I found a connection between their work and my own and sought to emulate and build upon their techniques as a kindred spirit.

In the 1990s, though, when I began showing my drawings and paintings in small, independent galleries across the United States, I could not help but notice that I was an outsider. I was rejected by mainstream galleries who embraced modernist-inspired artists and critic Clement Greenberg’s artistic philosophy. Greenberg believed that painting could not be three-dimensional, which was the domain of sculpture; it could not be representational, which was the domain of literature; and it could not generate dramatic effects outside its material, which was the domain of theater.

It took years before I began to realize that I was part of a broader movement. In 1998, Odd Nerdrum, a fellow painter that I greatly admired, declared that he was no longer an artist, but rather a “kitsch painter.” Disillusioned with modernist ideas that he saw as absurdist and that fostered apathy and ego in artistic expression, Nerdrum embraced his association with the technical skills of the Old Masters and sought to use their trade (as opposed to some pre-fabricated Kantian “genius” that critics said should be lying around inside of him) to render empathy on his canvases. Nerdrum could have cared less what society thought of him, and embraced large-scale narratives full of timeless archetypes.

Around this time I began to embrace more fully the archetypes of love, death, birth, and re-birth, and let them pervade my work. I would eventually find my path to Røvik Gård and study with Odd Nerdrum personally. Besides what he taught me technically, Nerdrum also left me with the lesson that, whether we are called kitsch, grotesque, dark, or low brow, narrative storytellers are painters searching for sentimentality. He showed me that this is an honorable pursuit, and that I should never apologize for being genuine. Instead, I ought to follow the path of those who came before me and search for clues along the way.

In a masterpiece, time and place are captured so vividly that a viewer is moved to the moment, to joy or sorrow more than tears. A masterpiece lifts a veil, exposing the heartstrings of life. It allows those heartstrings to resonate and reverberate in the depths of the human condition.

In our less than picture perfect world, finding an artist who can draw inspiration from life’s oddities, struggles, and melancholy is rare. Painters who can find meaning in worldly oppression and also have technical training in narrative storytelling is even more uncommon. Even for the few who possess both, issues showing their work arise because few venues exhibit work labeled “kitsch painting,” “imaginative realism,” or “dark art.” Because only a few galleries and museums exhibit realistic art with emotional depth, the chances that the public will be exposed to masterworks that drive them in any way to think at a given gallery show are slim indeed.

There is ample evidence, however, that those galleries and museums that do take a chance on grotesque realism reap the benefits of doing so. For instance, director Guillermo del Toro’s traveling exhibition of his personal collection of predominantly grotesque work, entitled “At Home with Monsters,” debuted in 2017 and drew record crowds across California and Canada, as well as in Minneapolis.

In 2019, the Dulwich Picture Gallery and Museum in London, showcased “Ribera: Art of Violence.” Old master works were shown alongside contemporary pieces, with over 40 works arranged thematically. In particular, paintings depicting the human condition in its raw form in striking narrative style were showcased. Human atrocities, religious martyrdom and mythological suffering rendered with chiaroscuro and naturalism featured prominently, and the reaction from the public was overwhelmingly positive.

When I have taken part in efforts to arrange shows focused on brutal realism, I have noticed similar enthusiasm. In 2012, I had the honor of helping to coordinate (and showing my work in) “At the Edge: Art of the Fantastic,” a groundbreaking exhibition organized by Brooks Joyner of the Allentown Art Museum. Co-curated by Patrick and Jeannie Wilshire, the show focused on narrative storytelling through painting and was one of the highest attended and most successful in the museum’s history.

In 2019, I showcased my traveling solo exhibit, “Urgency 2 Extinction,” with Iowa State University, IX Gallery, and Creighton University. The pieces I displayed were defined by socially critical subject matter addressing climate change, the death of pollinators, ongoing wars, poverty, and atrocities in the Middle East. The exhibition was almost entirely sold out at the end of its cycle, and my lecture at Iowa State University explaining that the tradition of storytelling in narrative painting is still alive drew a crowd of 300.

It has taken a while to educate collectors, but some galleries and museums, seeing an opportunity, are beginning to showcase artwork that is brutal and grotesque, as well as beautiful. The results in the last few years have been exciting. The number of painters willing to push boundaries and depict the brutality of this world is still small, but with support it is growing.

Museums have begun to connect the dots linking their permanent collections of old masterworks to modern narrative painting and are showcasing living masters alongside those of the past. They have also dismounted the high horse of Greenberg-style critical theory and decided to engage the public rather than lecturing to it. Painting demonstrations on old master techniques and educational talks connecting timeless storytelling techniques to modern trends in narrative art have proven popular.

This engagement is important because, in an age of social and political upheaval, the artist is an anomaly. Like the past masters, I have found vitality and life hidden amongst the layers of the human condition and have started breathing new life into the human form with visceral brushstrokes that are intimate, piercing, mesmerizing, and at times distressing. Being able to showcase that work has, I believe, helped viewers in some small way to make sense of the horror they see on the news and in their day-to-day lives.

My drawings and paintings evoke empathy and explore moments caught in time. In my narratives, I use the ancient Greek archetype of pathos (a quality that evokes pity), melancholy, and sadness as a wake-up call. The butterfly is a powerful symbol in my work, representing change, transformation, death, rebirth, and life. The monarch butterfly, in particular, which represents the mysteries of the soul, is a symbol of transition and hope that I have used in my art for 20 years. The monarch has the ability to lead us out of the darkness, confinement and restraints of oppression and into the light. So, too, can painting.

Related Article by Jeremy Caniglia > Step-by-Step Portrait Drawing: The Power of Line and Light

Connect with Jeremy Caniglia:

Website | Instagram

Visit EricRhoads.com (Publisher of Realism Today) to learn about opportunities for artists and art collectors, including: Art Retreats – International Art Trips – Art Conventions – Art Workshops (in person and online) – And More!

GREAT ARTICLE!!!

Yes a very good article, thank you.

Comments are closed.