One line, narrowing from thick to thin, can control the weight, movement, and emotion within a composition. See how in this step-by-step portrait drawing demonstration from Jeremy Caniglia.

Step-by-Step Portrait Drawing: The Power of Line and Light

BY JEREMY CANIGLIA

One line, narrowing from thick to thin, can control the weight, movement, and emotion within a composition. During the Renaissance in Florence, disegno (drawing) from life was central to a painter’s development and a daily activity for masters and apprentices. In fact, most of the modeling in the academy was done by studio apprentices posing as mythological gods or religious saints, sinners, or martyrs. During my time apprenticing in Norway under the master Odd Nerdrum I took part in a continuation of this tradition, modelling for several drawings and paintings.

Unfortunately, academic, skill-based teaching in drawing, painting, and composition is all but lost in high schools in the United States. A few academies, like the Art Academy in St. Paul, MN, and the DaVinci Initiative in Jersey City, NJ, have kept the torch of skill-based training alive for the next generation of youth. These schools embrace the Old Master traditions of Da Vinci, Michelangelo, and Raphael. Though few in number, they offer an indispensable guide for proliferating the teaching of art techniques as a skill set.

“In 1563 Cosimo, Grand Duke of Tuscany, the historian Giorgio Vasari, and Michelangelo presided over the birth of the Accademia della Arti del Disegno in Florence.” (1) At the Accademia, training first in drawing from master copies, then from Greco-Roman statues and poses, would slowly instill in an artist the ability to compose from life. The École des Beaux-Arts created a similar model that can trace its origins back to 1648. The primary goal of the École was to keep alive the soul, the genius, of antiquity. “One can see that in Ingres’s drawings from the École des Beaux-Arts that the human body, whether drawn from a model, a marble sculpture, or a plaster cast, seems to vibrate in the light, seeking equilibrium of movement. Training was based on the antique ideal of anatomical study, light, perspective, and analysis, combined with Greek thought and experimental science.” (1)

In the studio, the draftsperson will discover that the path they take with each line is a journey that they embark on alone. The foundational training leading up to this time was important to the development of their hand and their approach to the start of the drawing, just as the influence of past masters will meld into their approach and psyche. Equipped with technical tools, the artist can enter the creative loop, where we are left alone to discover just how alive a drawing can be.

The thread between the model and artist is a point in time allowed to speak eternally. The draftsperson has an array of options in front of them. They will decide what characteristics to emphasize in the sitter and how much value and tone to give the piece. They will come to find that less can sometimes be more and that parts left out are just as integral to a piece as those included. The Aristotelian idea of the golden mean, in which a desirable middle is found between two extremes, is key to the balance held in a master drawing. The artist cannot under-develop a composition, and yet must refrain from overworking it until it loses its emotion and beauty.

Related Article > Historical Approaches for Contemporary Portrait Practice

I feel there is a misconception in the academic world today that drawings are just studies for larger, narrative paintings. I find the same perception in contemporary galleries as well, which tend to showcase paintings before drawings. They feel that drawings do not hold the worth and weight of a painting. Even many artists today believe that painting is on a level above drawing. I would argue that many of the most talented painters lack the subtle, sensitive touch that is needed to imbue a master drawing with breadth and depth.

A portrait drawing, for me, is not just a preliminary study for a final painting. When done well, drawings are powerful narratives and compositions that hold their own against what are often labelled “finished” works. They are even at times more alive than paintings. Drawings from life have drama and pathos. They can emotionally engage the viewer, inviting us to ponder the beauty, love, and horror of our world. One unbroken line carries the whisper and fragility of a sitter’s portrait and connects us to a timeless gaze and the life that is or once was manifest in it. Even when the artist and sitter are long gone, the time capsule of a drawing lives. It breathes life into the next viewer that embraces the composition.

Leonardo da Vinci (1452–1519) stated that, “Though human ingenuity may make various inventions, which by the help of various machines answering the same end, it will never devise any inventions more beautiful, nor more simple, nor more to the purpose than Nature does; because in her inventions nothing is wanting, and nothing is superfluous”(2)

Da Vinci understood, through countless hours of observation and sketching, that nature held the keys to beauty. For those who peeled back their layers of preconceptions and opened their minds to the simple designs we have been given, the formal perfection of the natural world was self-evident.

Leonardo was a master of pen, ink, chalk, watercolor, and metal-point, but his greatest achievement is the sophisticated simplicity of his sketches and drawings. I would even argue that his drawings are more powerful than his finished paintings. In da Vinci’s drawings we get a vivid look at his creative process at its most honest and intimate. His drawings, for me, are like an actor’s best improv routines. We see quick, precise lines delivered with purpose, articulation, raw power, and spontaneity. His paintings, which could be compared to an actor’s performance in a play after much labor memorizing lines and pantomimes, have surface beauty but lack the raw emotion, empathy, and energy that comes through in the drawings.

I would also argue that there is a reason that almost 4,000 of da Vinci’s works on fragile paper survive to this day, compared to just 15 of his paintings. Patrons and collectors understood the power of da Vinci’s drawings. Disegno was the life-blood of his creative process, allowing him to understand and articulate emotional beauty, imagine battles, invent worlds, and conduct accurate, observational scientific studies of the human figure. Leonardo created extensive notes, sketches, and drawings that examine the nature of light and shadow, and each bristles with life.

Related > Watch: Expert Portrait Drawing Tip

Käthe Kollwitz (1867–1945), who I believe is one of the most profound artists of all time, has been a huge influence on my own personal subject matter and my understanding of drawing. Her line is at once a whisper and a hammer. It hits with force but threads us together delicately in its expression of the empathy of the human condition. We only have to spend a little time with her work to realize that we are looking at something so profound that it transcends time and place. Kollwitz’s understanding of the human figure and volume makes her drawings alive, as if they are coming off the paper surface in the same vein that Caravaggio’s chiaroscuro breathed life into his paintings.

Each line in her drawings, as Odd Nerdrum often reminded me, is a repetition of the expression of pain of losing a child and grandson to war. Kollwitz produced work that spoke of war, poverty, motherhood, and the plight of the working class. She was the first woman to be elected to the esteemed Prussian Academy of Arts, in 1933, but was expelled during the rise of Hitler, her work labelled “degenerate” by the Nazis.

Kollwitz’s life was intimately touched by tragedy and this showed in her drawings and etchings. She lived through both World War I, in which she lost her son Peter, and World War II, which took the life of her grandson Peter. The images created by Kollwitz have an incredible intensity, depicting the human condition on an emotional depth and level that few storytellers have achieved. Her drawings stand in a realm of their own as masterworks, not as studies for paintings. Her work speaks to us all, honoring our common humanity. It resonates with so many around the world because it is both intense and personal.

In my work, I have developed a love for intensely atmospheric drawing in my têtes d’expression (expressive head studies). In each portrait drawing, I struggle to capture the expression and life of the model, rather than their exact likeness. The specificity of the individual I am drawing and my ability to capture the idiosyncrasies in the way they convey emotion are critical in the process. It is important that every stroke has purpose.

The portrait drawing is an orchestration of soft and hard edges, mixed with careful observation to convey the different subtle emotions of the model. I do not try to define every detail and line. Rather, I seek balance. Integrating a less-is-more technique with the rich tonal effects that I am trying to achieve can be very difficult. Drawing is about patience and a carefully calculated balance of mark making. I have found a sense of melodic melancholy in my ritual of preparation and planning the pose that speaks to me. With each drawing, I launch into the creative loop of portraiture with an idea of what could be and what will be when I finish. I use a combination of various colored chalks and charcoals to produce an eternal portrait.

Drawing Portraits: A Demonstration

(Photos for this article were taken by David M. Weiss and used with his permission)

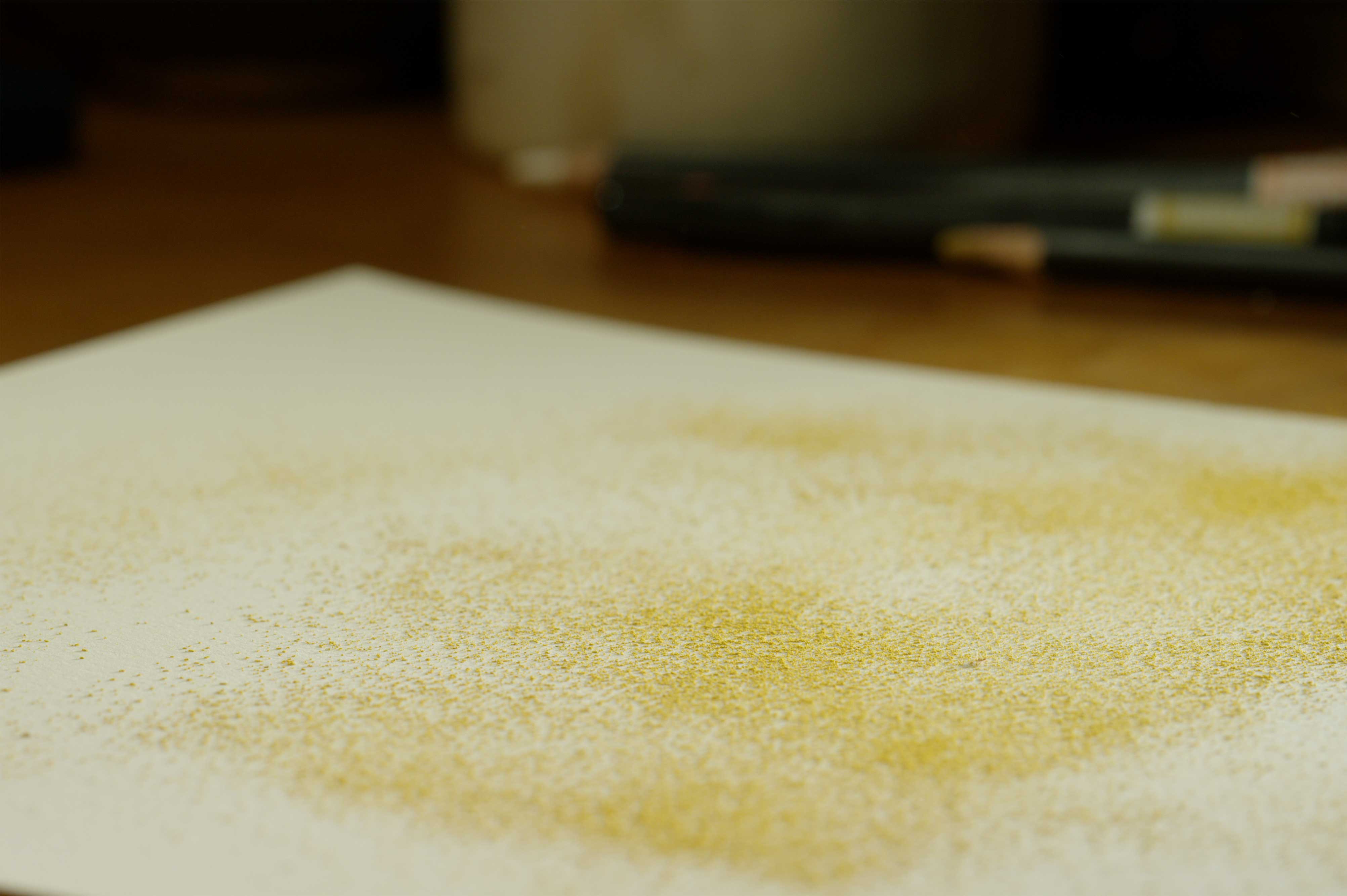

Step 1) For my portrait drawings, I use Canson paper, and for drawings that will take a few weeks I prefer to use the Fabriano Roma paper. I make sure all my Nitram charcoals and Derwent tinted charcoal pencils are sharpened into thin, long, tapering points using sandpaper.

The first thing I do is what I call hand toning the paper. I apply a nice, even dusting over the paper using a 180 grit sandpaper and a Prismacolor NuPastel chalk stick. I use a combination of the terre de sienna and raw sienna as I dust the surface.

Step 2) I then take a chamois, which is a soft, pliable leather cloth, to smooth and blend the color to an even tone across the entire surface of the paper. I have studied a number of Old Master drawings as well as Käthe Kollwitz’s work, and I feel that the warm undertones set a nice, unified moody substrate that can poke through areas of the opaque charcoal to balance the composition.

It may take 2 passes horizontal and vertical to get the paper blended evenly.

Step 3) I start by capturing the skull structure and large landmarks on the face. No details, only big shadow shapes. I use my Nitram H, then HB, and then B for dark shadows. It is important to capture the overall geometric shapes and start building on light lines, with more weighted lines to come once you have the form and foundation set.

Step 4) I leave the under powder of the toned paper showing through the face with warm elements and a rich play of warms and cools as the piece progresses. I will then use shadows and highlights to increase the sense of drama in this naturalistic portrayal of the woman with butterfly.

Step 5) Next, I will go into the portrait with my Derwent tinted charcoal pencils. One important quality that is often overlooked is line weight. I can’t stress enough that a drawing comes to life when you vary the intensity and boldness of your stroke from thick to thin. I will then use my fingers and blenders to lightly blend my darker edges into halftones.

Step 6) I will then build my darks up again and knock them down with a soft paint brush. It helps create the ineffable emotive force in my portraits. The play of hard and soft edges helps blur the realism into a portrait that moves beyond the idea of just sketching and into capturing the eternal.

Step 7) I will draw nonstop for about 90 minutes with breaks for my sitter every 30 minutes. It usually takes three 90-minute sessions to fully capture the model.

Step 8) When I feel I have an overall grasp on the composition I will add white chalk for lights and highlights. The whites rise out of the background, giving a nice chiaroscuro effect. I will then vary the texture and thickness of my strokes of black chalk to create a range of effects. On the left side of the sheet, for example, a mass of chalky lines silhouettes the butterfly and edge of the woman’s hair. I then used the Nitram charcoal to add variations of line weight around the edge of her chin, giving the impression of wispy hair that softens into the hollows of her neck and cheeks. The yellow earth tone of the paper serves as a middle tone between the black outlines and the white gleam on the woman’s neck, cheekbone, and ear.

Step 9) As I finish the drawing, I make sure that the line, value, and overall composition demonstrate a balanced, controlled transition of tone and mood. The final result should emphasize and enhance the intrinsic drama, beauty, and timelessness of the form.

In the end of my portrait drawing process I will make subtle edits with my fingers and blending stump in the finished areas to blend them into a seamless sfumato effect that gives the drawing a dreamlike feeling. I check to see if there is anything that I could add or take away from the composition to make them stronger and balanced. I model from the outer contours to the interior shadows. I am committed to the idea of each portrait portraying a subtle tension in the pose. The butterfly is used as both metaphor and symbol in my work, representing change, transformation, death, rebirth, and life. In this series of butterfly portraits, I am earnest in my intent to capture the ethereal, softly sensual beauty and melancholy grace of these strong women who are captured in a moment in time.

About the Artist: Jeremy Caniglia (b.1970) is from Omaha, NE.

Caniglia is known for his emotionally charged and often unsettling work, which focuses on the human condition. A successful painter, his work is showcased in private collections around the world. His art is published worldwide on a regular basis, and he has contributed to both joint and solo fine art exhibitions at museums and galleries that include the Society of Illustrators (NY), the Allentown Art Museum, the Walters Art Museum, Salmagundi, Abend/1261 gallery, Paul Booth-Last Rites Gallery, and the Joslyn Art Museum.

Caniglia holds a BFA from Iowa State University, an MFA from the Maryland Institute College of Art, and an M.Ed. from Creighton University. Caniglia also studied at the Nerdrum School in Norway with Odd Nerdrum.

Caniglia’s art has been featured in various magazines and publications, including the Washington Post, CNN, Spectrum Fantastic Art Annuals, IlluXcon Art Annuals. He has worked with such authors and bands as Stephen King, Ray Bradbury, Max Brooks, Peter Straub, William Peter Blatty, Michael Moorcock, Sigur Ros, and Blink 182.

His work has appeared in numerous books and movies produced by Random House, Pyr Publishing, Cemetery Dance Publications, Dorchester Publishing, Easton Press, IDW Publishing, Anchor Bay Entertainment, IDT Entertainment, Showtime Networks, and Warner Brothers among others. Caniglia received the 2004 International Horror Guild Award for best artist in dark fantasy, the IlluXCon 2012 artist award, the 2015 Iowa State University College of Art and Design Achievement award, and the 2018 NC Wyeth Merit Award from the Salmagundi Gallery in NYC.

Caniglia’s work continues to push boundaries; his devotion and advocacy of the figure and human condition are a felt reality full of symbolism and metaphors that transcend time and place.

(1) Gods and Heroes: Masterpieces from the École des Beaux-Arts, Paris, Publisher: American Federation of Arts and D Giles Limited, 2014

(2) The Notebooks of Leonardo da Vinci – On the Origin of the Soul (passage 837), edited by Jean Paul Richter, 1880.

Amazing! So happy to see this and learn. This master have no idea how useful this is to me. Thx Realism Today. Thanks Jeremy Caniglia 🔝🔝🔝

Comments are closed.