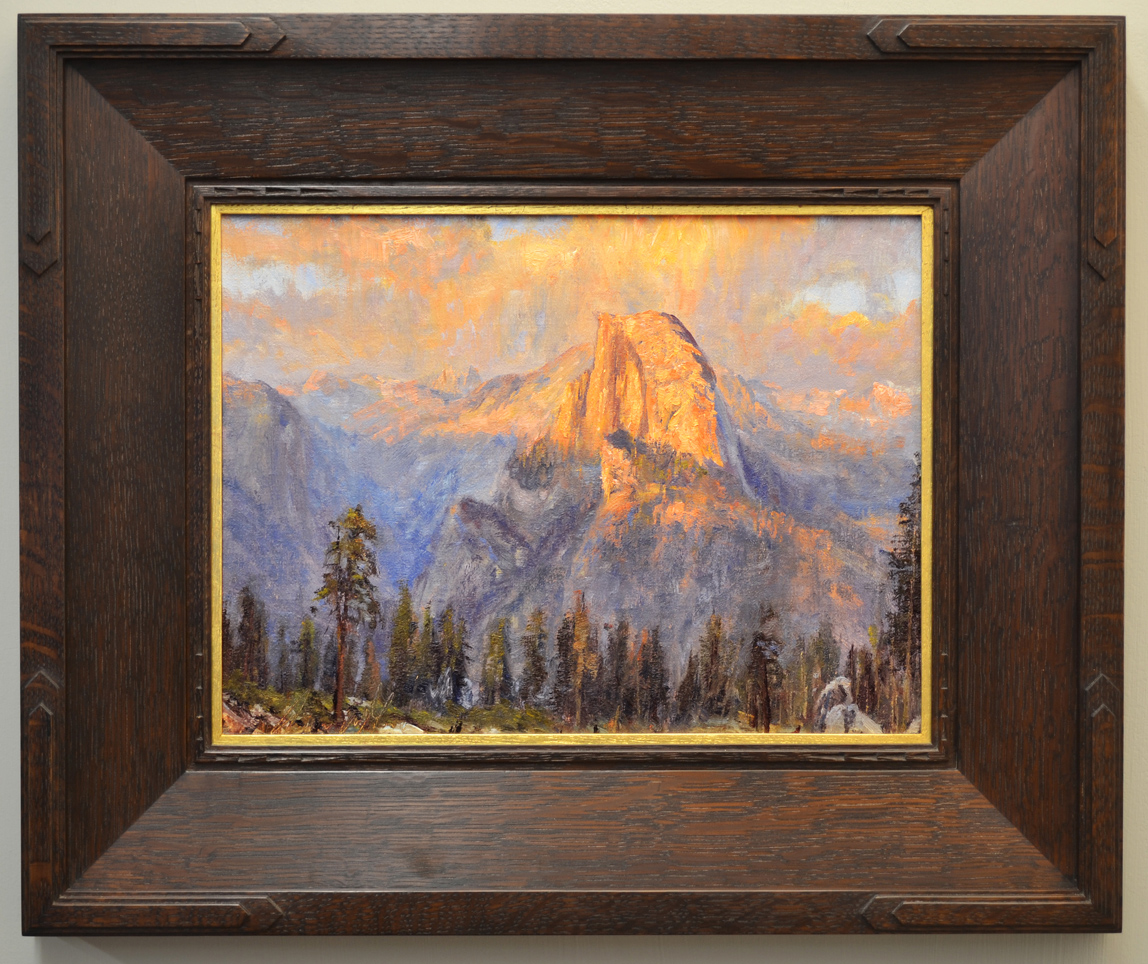

Why framing is a critical element of your final piece of art, and how it’s perceived by the world at large.

BY TIMOTHY HOLTON

If you’re a pictorial artist, you probably see picture framing as a problem. If you show in galleries, the frame is a big and bothersome expense.

But more than that, it’s an artistic problem — something that undeniably affects how your work is perceived, and even whether it’s perceived — but the very nature of which is outside and foreign to the art of painting.

The difference between a good frame and a bad one seems almost arbitrary — a matter of chance. The problem of the frame, most painters seem to think, boils down to how to avoid choosing the wrong frame — especially if you’re paying a lot of money for it.

Every problem is also an opportunity. Avoiding choosing the wrong frame means a chance to choose the right frame. And a frame, as I will argue, cannot be indifferent. A frame that is neutral or indifferent to the picture is a bad frame; it has failed the picture and is harmful to it.

The reason that’s true goes to the very nature of paintings and their relationship to the world. To the extent that the life of a painting depends on a vital relationship to the life around it, that life depends first of all on its immediate setting — that is, on the frame.

The relationship of paintings and frames is an extraordinarily troubled one, and the root of the problem painters have with framing their pictures.

The true nature of that relationship is difficult to penetrate because its problems go back centuries — to the Renaissance, when the unity of the arts began to dissolve. But it is not at all hard to see how real and how important the relationship is.

If more than a few painters have been put off by frames “killing” a painting, most have also seen a frame bring a painting to life — transform it, elevate it to another level of significance and effectiveness.

What I want to do is help you, as a painter, navigate this troubled territory bounding your painting and understand this transformational power of the right frame. I want to share what I’ve learned over four decades as a frame maker and picture framer — and just as importantly, picture re-framer. I’ve witnessed and reflected long on the use and abuse of frames — how a frame can help or harm a picture.

My objective here is to share my observations about what makes a frame right or wrong for a painting, as well as what history has taught me about this fraught relationship between pictures and their frames.

Above all I want to convince you that frames matter and deserve serious consideration.

Practically speaking, for the painter faced with the problem of framing his or her painting, what is that difference between the right frame and the wrong frame? That practical side of the problem I’ll tackle in a later article. What I want to do here is lay the necessary groundwork, which is gaining a deeper understanding of what frames fundamentally do, and the significance of that.

Engaging most productively in the creative work of framing requires overcoming a number of common misconceptions about the frame and, instead, reaching a true understanding of its purpose and role — what we’re actually trying to do when we frame pictures.

A Broken Harmony

What is the nature of the relationship between the picture and the frame? In short, it’s a broken relationship. One sure conclusion you could draw from taking a stroll through art history at a museum is that after hundreds of years of frames being universally used and even physically integral to pictures, and after centuries of some of the finest carving and craftsmanship being lavished on the settings around pictures — physical evidence of the care people felt for both pictures and their settings — painters suddenly made up their minds that frames were dispensable. They could take ‘em or leave ‘em. Whatever. You decide.

Pictorial artists, largely indifferent and frequently hostile to the frame, surrendered to galleries and patrons the decision of how paintings should be framed. And compared to frames made just a century before, the quality of frames plummeted as fast as did their use — clear evidence of a pervasive lack of care about them.

The corners, once properly joined by real woodworkers using proper joinery — such woodworkers being called, appropriately enough, joiners — were now put together with nails. As frames fell off paintings, their corners all broke. The twentieth century seems to have solved the problem of the frame by simply neglecting it and letting it lapse in to decay. As a culture, we appear to have decided that frames don’t matter.

To archaeologists, who study material culture as evidence of the nature and character of societies, a dramatic and extensive shift in something like the presentation of works that have traditionally been expressions of the culture’s highest values and ideals, of things it most admires and reveres, signals not only a change in the meaning and purpose of those works of art, but the real place and presence of those values and ideals and thus very character of a society. It’s a transformational change.

But vast as they are, such questions lie beyond the scope of this article.

Suffice it to say that these are matters of huge significance which, abstract though they may seem, are reflected in the very real and observable relationship of paintings to the wider world — a relationship dependent largely on the picture frame.

So thinking about frames is thinking about significance itself. As John Ruskin famously put it, “All true art is praise.” Framing begins with the understanding that paintings, no matter how humble, are inherently significant as human expression of what is praiseworthy, and deserve our fixed attention and the effort, skill, and knowledge required to commit them to oil and canvas — media that were developed to endure and thus record for many years things that greatly matter to people.

And that’s really the only reason we frame anything: Because it matters, because it’s significant. Everything the frame does begins with that recognition and understanding.

But if pictures matter — which readers of this magazine no doubt feel they do — then frames must matter because frames provide pictures with significant places that allow them to affect our ideals and our lives.

Frames matter because pictures matter, and pictures need the complementary relationship provided by the frame in order to sustain and project their expressive power beyond the illusion depicted on the canvas and into the reality of the surrounding architectural setting and the life it shelters.

That sounds theoretical, but the visceral response we experience when we see a painting in a harmonious and suitable frame — an experience akin to revelation, and feeling as if we hadn’t actually seen the painting before — can be attributed to the very observable potency of a successful frame (or, I should say, a successfully framed picture). Because what makes a frame successful is its enhancement of the expressive powers of the painting.

What is the difference between the frame that “kills” a picture and the frame that “brings it to life,” to use two common and very revealing descriptions of the effect of a frame on a painting?

I believe that, due largely to the rampant abuse of frames, we no longer trust and understand them — what they can be, how they can help and serve paintings. We no longer understand the relationship between pictures and their frames because we don’t understand the relationship between pictures and the life around them.

As the massive cultural shift away from frames suggests, much larger and more profound matters lie underneath this loss of understanding. The abandonment of the frame is no superficial matter of changing fashions, but a reflection of far more profound shifts.

In trying for many years to make sense of this troubled and precarious status of frames — despite their evident effectiveness and potency — I’ve concluded that there are four great reasons we don’t understand frames, all of which are due to changes in the role and place of paintings in civilization.

First, we have forgotten (or chosen to ignore) the inevitable relationship just eluded to between pictures and architecture.

Second, our relationship to pictures has changed so radically that I believe the general public no longer truly understands what a picture is (although you, as a painter, are probably an exception to this).

Third, inextricable from the general disdain for frames is our unique modern idea of freedom — most of all, the freedom of expression — and unsurpassed reverence for that idea; and frames (especially due to their history of being abused and of mediocre frames degrading paintings) came to be seen as having no purpose but to literally box in the picture, constrain and limit it — and therefore limit the artist.

Our uniquely individualistic concept of freedom and independence, however, fails to appreciate that true freedom depends on the nature and quality of human relationships as much as it does on personal expression.

And finally (although it sounds like a stretch, but it’s not), we’ve lost touch with the original understanding and meaning of the word art; that is to say, what art is, the word’s very definition — or more accurately what the arts are: the place, purpose, and role of the arts.

And because paintings, in being elevated to the status of fine art came to represent all art generally, the flawed understanding we have of art very much shapes—or mis-shapes—the way we frame pictures.

At its root the problem of the frame is summed up by the question, Will your work be connected to the world or separated from it? It’s a difficult question that touches on the most profound concerns of pictures and artists and their relationship to the world — or lack thereof.

The Inevitable Frame

A common response to the problem of the frame is to refuse to face it, and to either adopt the current fashion and convention in frames that are mass-produced and marketed to exhibiting painters, or to take the minimalist approach — narrow-as-possible molding (often “floaters” that are both typically narrow and appear not to touch the painting), or no frame at all. After all, what is the point of the frame? Does the frame matter?

Throughout most of history people regarded an unframed painting as an unfinished painting. So frames clearly had great significance — they did indeed matter. The problem of the frame was one of how to frame the painting. Now, the problem begins with whether to frame.

As a framer, I’d be the first to admit, for reasons I’ll get in to later, that not every painting benefits from my trimming its edges with molding — or at least very substantial molding.

Abstract paintings often don’t call for much of a frame at all. But every picture, even an abstract one, is affected by its setting and context, and by its handling — the care it receives as evidenced by the effort to protect its edges. Such care is more than a utilitarian necessity. It indicates some measure of regard and appreciation for the painting.

Beyond that every picture benefits from a suitable setting — and it’s inarguable that there are suitable and unsuitable settings. As every painter knows, elements of a painting — color being a prime example — are tremendously dependent on context for their effect. But the larger point is that, in the sense that paintings necessarily have settings — after all, they exist somewhere — the frame is inevitable. It’s impossible for a picture to hang on a wall “unframed,” since at the very least it’s framed by the surrounding wall.

So the real question isn’t whether or not to frame a painting, but why we think that’s even an option. The frame, the immediate setting of the picture, establishes in several important ways that serve the effectiveness of the painting, its relationship to the wider world and above all our sense of its significance to that world.

How did we come up with the notion that we can get rid of the frame? Somehow we lost our understanding of and appreciation for what frames do. It’s time to take a step toward restoring that understanding and appreciation — and to repair the natural and necessary, but broken, harmony between pictures and their frames.

ABOUT THE AUTHOR

Timothy Holton was born and raised in Berkeley, California, where, in 1975, he began making frames at the highly regarded shop Storey Framing. His frame designs arise from a lifelong fascination with architecture, stimulated early on while living and traveling in Italy and Greece, and cultivated at home by ongoing awareness of the Bay Area’s great early twentieth century architects and designers (figures like Bernard Maybeck and Julia Morgan).

At least as strong an influence were the vernacular brown shingle and Craftsman homes of Berkeley, Inverness, and rural northern California. In more recent years he has studied the California Decorative Style work of turn-of-the-century San Franciscans Lucia Kleinhans Mathews and Arthur Mathews.

In 1988, after studying history at the University of California at Santa Cruz, and enduring a brief career in live theater, Tim turned his attention back to picture framing, undertaking to develop his skills in joinery and carving that distinguish his work.

In the Spring of 1993 his furniture and mirrors were displayed at the Oakland Museum’s special gallery of contemporary artisans during the Museum’s exhibition “The Arts and Crafts Movement in California: Living the Good Life”. The warm response spurred him later that year to open Holton Furniture and Frame. (In 1999 the business name was changed to Holton Studio Frame-Makers to reflect the shop’s exclusive focus on picture and mirror frames.)

Contact Timothy Holton through HoltonFrames.com to learn more about framing your paintings.

Related Article > Know Your Art Supplies: Royal Talens Spotlight

Visit EricRhoads.com (Publisher of Realism Today) to learn about opportunities for artists and art collectors, including: Art Retreats – International Art Trips – Art Conventions – Art Workshops (in person and online) – And More!

Wonderful stuff – thanks for sharing.

Marty

Comments are closed.