Through the process of painting we have the potential to peel back the layers of simulacra and reveal a deeper truth. The search for that truth is as much an aspect of the great traditions of art as is the value of craftsmanship . . .

BY JORDAN SOKOL

“How do we fit what happened to us into life without turning it into an anecdote with no teeth and a punchline we’ll mouth over and over for years to come, ‘Tell the story about the impostor who came into our lives—’ ‘That reminds me of the time this boy—.’ And we become these human jukeboxes spilling out these anecdotes. But it was an experience. How do we keep the experience? That’s why I love paintings.” – Ouisa Kittredge from Six Degrees of Separation

These lines, spoken towards the end of John Guare’s play, echo a dilemma in the human impulse to reconcile our relationship with the world we live in, and inspire us to contemplate larger questions about what it means to be human. How do we process the great spectrum of experiences that we all live every day into something meaningful? How have the greatest artworks in history avoided the fate of becoming mere anecdotes, and speak to us in a language that is timeless and resonant?

To stand in front of Rogier van der Weyden’s painting, “The Descent from the Cross,” in Madrid’s Museo del Prado, is spellbinding. Although the painting, created around 1435, is clearly rooted in religion, it has a visceral power that rises above its iconography. Just as in Michelangelo’s “Slaves,” or Mozart’s “Requiem,” there’s a pathos and humanity that touches on something larger than itself, something universally human.

Art, at its best, has the power to transfix us, to shake us from our complacent lives, and make us aware of a collective existence greater than ourselves. Van der Weyden’s masterpiece offers us the possibility to experience the sacred, but it’s a sacredness that isn’t solely confined to the world of religion. Paradoxically, it’s a sacredness rooted in the human experience.

Related Article > This is Not a Nude: Figurative Art by Rose Frantzen

For the moment, let’s consider a broader interpretation of “sacred,” not necessarily as an association with divinity, but as the feeling of an intense connection to something that inspires a form of ceremony in order to consecrate that experience. In this case the process of painting becomes that ceremony. Thus, a painting has the potential to become more than just an image, but a consecrated reality. Through the process of painting we have the potential to peel back the layers of simulacra and reveal a deeper truth. The search for that truth is as much an aspect of the great traditions of art as is the value of craftsmanship, and ultimately the two become interdependent.

One of the unfortunate aspects of the modern era has been a cultivation of a culture of exploitation. In such a culture an object’s value exists only in as much as it can be used or exchanged for something else. This perpetuates a type of nihilistic worldview where nothing seems to hold an intrinsic value. This worldview has changed our relationship to the function of art, and even more tragically has diminished society’s conception of the potential of art. A culture of exploitation ultimately becomes the great desecrator of civilization. It annihilates the substance of authenticity and replaces it with a hollow caricature. Culture is reduced to entertainment and art becomes kitsch.

This is relevant to the challenges that figurative artists face today because it makes us aware of the differences between “image” and “consecrated reality.” William Rothenstein, a painter and friend of Sargent, wrote of his virtuoso colleague, “ . . . and yet in his brilliant rendering of the men and women who sat for him, he seemed to miss something of the mystery of life.” Harsh words for a painter celebrated as one of the greatest of the nineteenth century. And yet perhaps Rothenstein was acutely sensitive to the more profound and ineffable qualities of being that art can aspire to take part in.

Rembrandt’s “Self Portrait, Aged 51” transcends the realm of portraiture. It is more than just an image or imitation of reality, it is the creation of a reality—not representation but presentation. It is a realism separate from that of a photograph, created in a world that had never seen one. Rembrandt defines the limitations of the term “visual arts” and elevates painting to the realm of synesthetic experience.

Just as the cave paintings of Lascaux and Chauvet were born out of ritual and not just meant as decoration, what speaks to us in Rembrandt’s painting is not merely his image, but the substance of the ritual from which the painting has been borne out. “It’s not art, but an extract of life,” to borrow a phrase from the Spanish philosopher Jose Ortega y Gasset.

The greatest artworks in history have avoided the fate of becoming mere anecdotes because they are the consequences of a meta-dialogue that’s continued since the dawn of human consciousness. Whether it be Van der Weyden’s search for humanity in the divine or Rembrandt’s struggle to find redemption, ultimately we are all trying to reconcile ourselves with the ideas and feelings of what it means to be human.

If there’s a sense of cynicism in the art world today, as lamented by many artists, critics and historians, then it remains symptomatic of a larger problem that extends beyond the realm of art. It’s a reflection of a complacent and nihilistic society, one that doesn’t enable the time for genuine contemplation, or cultivate the notion that something can have meaning beyond its exchange or entertainment value. For art to fulfill its highest potential it will take more than virtuosity and skillful craftsmanship. It demands a conscious and engaged participation in the search for identity, and the recognition that we have the ability to not only experience the transcendent but also to instill meaning.

As Viktor Frankl declared, “What is demanded of man is not, as some existential philosophers teach, to endure the meaninglessness of life, but rather to bear his incapacity to grasp its unconditional meaningfulness in rational terms.”

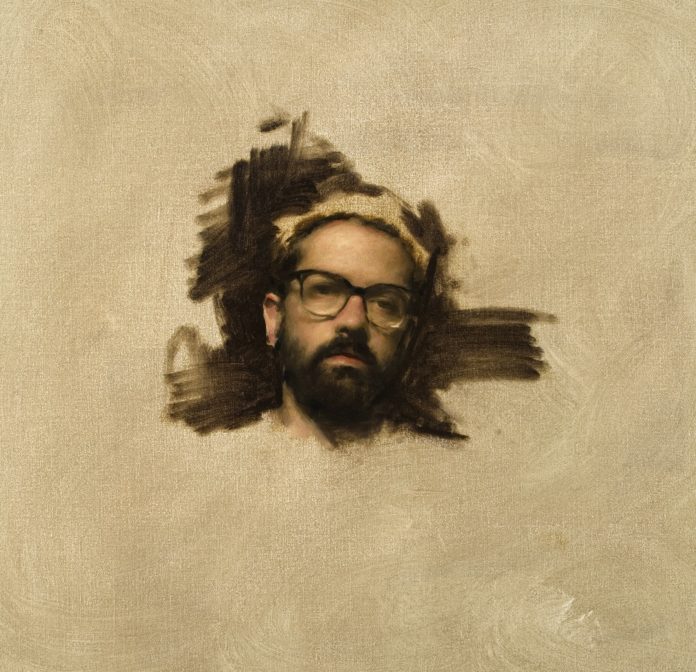

Jordan Sokol of the Florence Academy of Art (U.S.) taught a two-day course on the basics of drawing a live model at the first annual Figurative Art Convention (FACE).

Learn more about Jordan Sokol at: www.jordansokol.com.

> Visit EricRhoads.com (Publisher of Realism Today) to learn about opportunities for artists and art collectors, including:

- Art retreats

- International art trips

- Art conventions

- Art workshops (in person and online)

- And more!