Edward “Ted” Minoff explains how to paint waves by breaking the subject down into various components.

An Artist Catches His Own Wave

By Charles Raskob Robinson

Edward “Ted” Minoff (b. 1972) is an artist who gets things done. Just 10 years after his first lesson in fine art, he became an instructor at Manhattan’s Grand Central Academy of Art, and later an adjunct professor at Columbia University. Today, based in Brooklyn, he is a Signature Member of the American Society of Marine Artists, and in 2006 he co-founded (with the artists Jacob Collins, Travis Schlaht, and Nicholas Hiltner) the Hudson River Fellowship, which seeks to revive not only the skills of the Hudson River School of landscape painters, but also their artistic, social, and spiritual values.

Minoff says he is truly a “New York boy”: his father’s family name (Minoffsky) was anglicized when they arrived at the turn of the 20th century, and his mother’s family came from Sicily. At the Ethical Culture Fieldston School in the Bronx, he pursued a challenging academic curriculum, but also the arts and crafts, alongside classmates of diverse nationalities and races. After two years at Vassar College, he transferred to New York University’s Tisch School of the Arts, where he majored in film and television.

Wait . . . film and television? Like many of his contemporaries, Minoff believed that it was impossible to support oneself as an artist pursuing realism in the academic tradition. “It simply was not an option,” he recalls. “So I went into film, where I could earn a living by creating animation art.” Yet his career in animation was short-lived; no sooner had he begun — first working for Ralph Bakshi, the legendary producer of 20th Century Fox’s first animated film, then creating his own partnership to make animated television shows and commercials — than he began studying part-time at the artist Jacob Collins’s Water Street atelier in Brooklyn. There he learned that it was possible to earn a living pursuing realist art. Fortunately, he had practiced the art of animation long enough to deploy it later, when he turned his attention to marine imagery.

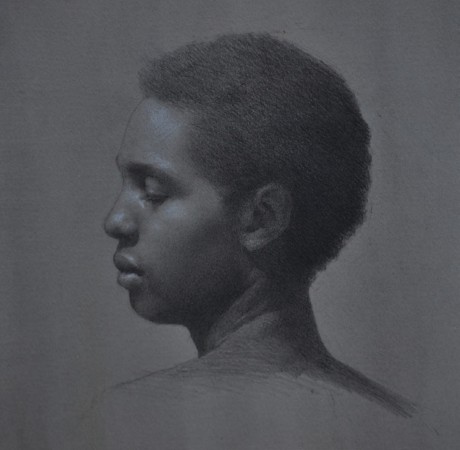

But first, he shifted to a full-time schedule with Collins for a year, then spent another year at Daniel Graves’s Florence Academy of Art, where he focused on classical drawing and Old Master painting techniques. “As part of my training,” Minoff says, “I copied a lot of the Masters in European museums such as the Prado and the Louvre, and also in New York at the Met and the Hispanic Society of America.” When he returned home in 2001, he began to exhibit actively, and, five years later, to teach with Collins at the newly established Grand Central Academy.

THE CHALLENGE OF PAINTING WATER IN MOTION

As successful as he was during this comparatively short period of time, Minoff sought more. “I am a New Yorker,” he says. “We have water all around us, and I grew up spending a good deal of time at a beach house my family has on Fire Island [on the southern shore of Long Island, facing the Atlantic Ocean]. But when I took the lessons I had learned from studying Sorolla and other impressionist landscapists and applied them to painting water, especially water in motion, I failed.

“The turning point came when I went to the National Academy Museum to see a brilliant exhibition about William Trost Richards [1833–1905]. I realized that Richards had spent a good deal of time picking apart wave structure in order to understand how it works. I decided that I also needed to master the structural mechanics — the anatomy — of waves. So I put away my paints, took my pencil and sketchbook to the beach, and patiently studied a given aspect — the same aspect — wave after wave, making notes of the moments of that aspect in my sketchbook all the while.”

Related Article > The Art of Jeremy Lipking and Why It’s “Rooted in Nature”

Minoff recognized that this was a very complicated puzzle, and that wave structure was but one of its missing pieces. Among the others were composition, color, and value — not to mention paint application. “I realized that unless I could break it all down into different components, it was unlikely I would master it,” he says. Perhaps it was subconscious, but it appears that Minoff resorted to the analytical techniques he had employed in animation when faced with similar complexity.

Back then, he would begin with an idea worth developing, “wherever it may have come from,” and create a storyboard to illustrate it. “This meant getting a sense of what it would look like — a feel for the evolution of the story, and doing a couple of different frames from each scene. If it still offered promise, I would create more scenes, adding more information and more continuity. Then finally I got down to the tedious work: creating frame after frame until done. This was an analytical process, constantly focusing on the basics before investing in refinements, working on one understandable facet at a time in what is an enormously complicated undertaking. It is all clear enough once you do it, but understanding the underlying analytical process makes it so.”

Minoff continues, “As [far as how to paint waves] on the beach, the process is quite similar: start with an idea and invest time in seeing if the idea can be developed successfully. This means doing tons and tons of small pencil sketches in notebooks. The key is observation and more observation, until you begin to have a fundamental understanding of the sea. This constitutes the necessary input for composing and constructing a painting in the studio.”

But why not take “tons and tons” of digital photographs, instead of investing time in sketches? “There is a world of difference between going into your studio armed with sketches based on direct experience versus relying upon photographs,” Minoff says. “Those frozen fractions of a second of visual information in photographs cannot compete — simply cannot compete — with all that the brain absorbs through the eyes, ears, and nose while observing the pounding surf. It cannot portray the human experience — and that is what interests me.”

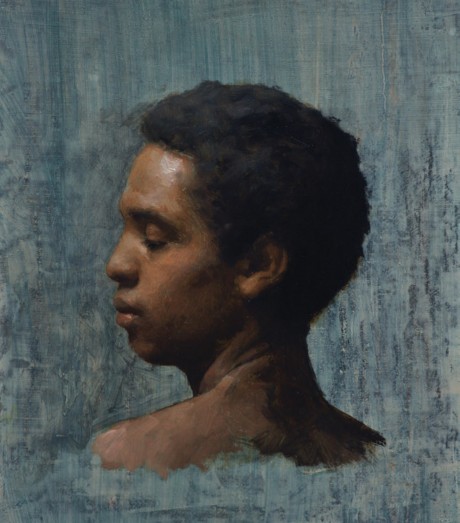

With an idea in mind and many sketches in hand, Minoff has the equivalent of a storyboard in animation art. He has the basis of a painting that relates to what he wants to say to the viewer. “But, again, if I were to undertake the composition at the same time as I addressed the complicated color aspects, I would be overwhelmed, so I focus on one thing at a time,” he says. “Eventually I have in hand the composition, the chosen hues (colors), values (lightness and darkness), and chromas (purity of hues or colors). Then I can make the first of several small sketches on toned paper, using graphite and gouache to help develop a strong sense of light. Next, I paint small panels (measuring 6 x 8 inches) to help the image evolve until one scene excites me. This leads to a larger study (usually 12 x 16 inches) to see how details might be best handled, and to confirm the choices of hues, values, and chromas.

“Once I know what color is to go where and how it will interact with its neighbors, I can concentrate on paint application. This is an important aspect in rendering water — thickness or thinness, transparency or opacity — and now I am free to concentrate on it.” This is another, and final, example of breaking down the process into phases, a strategy that Minoff traces back to his days in animation.

His painted canvases of the ocean are purposefully wide because, like his 19th-century role models, he seeks to envelop viewers so that they feel almost as if they can hear the surf and smell the salt air. “I am not just interested in the technical rendering of a scene, but also in creating a human experience for the viewer. Size, in this case, really helps.”

In addition to Richards, Minoff has found inspiration in capturing mankind’s encounter with the sea through the Maine paintings of Winslow Homer (1836–1910), and also the early works of J.M.W. Turner (1775–1851) that portray human involvement in storms, shipwrecks, and heavy seas. “I find it curious,” he says, “that the more I study Turner’s early works, the greater appreciation I have for his later ones — the nearly abstract fields of light I had not related to before.”

Article reprinted with permission from Fine Art Connoisseur magazine

- Visit PaintTube.tv to learn how to paint waves and much more in the style of contemporary realism, and much more.

- Join us for the next annual Realism Live virtual art conference and study with the world’s best realism artists.

- Become a Realism Today Ambassador for the chance to see your work featured in our newsletter, on our social media, and on this site.