Steven Assael could easily draw any sitter into classicized perfection, but he has more interesting plans for his narrative paintings.

By Peter Trippi

“Every painting starts with an emotive urge that may or may not be connected to a narrative idea,” says the New York–based artist Steven Assael (b. 1957). “I’ll have a sense of what I want but am open to chance.” Being open to the distinctive personality of his model, to the way light falls on the form, to the atmosphere in the studio that day — all of this openness can potentially go very right, or very wrong. In Assael’s well-trained and experienced hands, we know it will head in an intriguing direction.

“I usually start,” he continues, “with a visual, thematic idea — brides, for example — but the narrative evolves, its subtleties articulated as the painting develops. I select what is observed to support any change in feeling, or draw on memory, or respond to the unexpected. Over time, my sitters reveal themselves, and their individuality becomes part of the narrative.” In this context, you might expect Assael to have a tiny stable of tried-and-true models on call, and indeed he does have some favorites, yet he has also been known to ask strangers on the street if they will pose.

Clearly this is a man fascinated with who other people are, which makes his regular allusions to film directing all the more insightful. “I allow for the sitters’ performance to interfere with my concept,” he says. “I think of sitters as actors, revealing an outward formality and an inner history. As a director, having a strong actor can change everything, can steer the narrative in one direction over another. The moments in sequence embody the fullness of movement and an experience.”

The filmmaking metaphor is particularly potent because Assael is outspokenly opposed to working from photographs: “The great advantage that painting from life has is the embodiment of what is expected and unexpected. Chance cannot enter the process this way with photography. Photos can be helpful for general references, but I’m really all about how ideas are generated by the memory and synthesis of experienced perceptions.”

NARRATIVE PAINTINGS: GOING DEEPER

“I don’t consciously look for a certain type of person to draw or paint,” Assael claims, yet somehow we know that’s a former Assael model across the room during his exhibition openings. Though he has depicted all kinds of people, he is best known for young men and women from the city’s edgier neighborhoods: possibly tattooed, pierced, dreadlocked, or all three, and usually endowed with abundant hair; the models might be goths, teens, hippies, punks, or homeless. They might also be nondescript, yet always Assael finds a way in — as outlined above — a way for us to penetrate the personality with him. He talks readily about pretext and subtext: “Pretext is the outer persona we create, like a businessman’s suit — a manufactured persona. Then underneath that, there’s an individual persona that we shelter. When I paint a person over time, I create a relaxed setting, and try to think of my sitter in a dignified way.”

The sitters he records are generally ignored in fine art circles. Assael shows us why they are worthy of attention, without idealizing them. His nudes, for example, are frank and sensual, yet not so realistic as to be erotic (à la John Currin) or grotesque (Jenny Saville).

Related Article > Step-by-Step Portrait Drawing: The Power of Line and Light

Assael carries a sketchbook everywhere, and indeed drawing is at the very heart of his enterprise: “It is not just about expressing a well-articulated visual response to an object; it is deeply connected to a natural impulse.” Using pencil, ink, charcoal, or crayon on paper, he could easily draw any sitter into classicized perfection, but he has more interesting plans. Whether he is drawing models for their own sake or as studies for an oil painting, Assael makes a virtue of the paper’s natural color and imparts additional texture by using a fingernail, razor blade, eraser, or other implement to enliven the surface and bring our eye where he wants it to be.

Whether they depict an individual, pair, or group, whether they are small or large (some tableaus are 10 feet wide), Assael’s compositions are always ambitious in some way. A key asset is his knack for intriguing compositions, often off-center or featuring areas left indistinct so that our imaginations can fill in the blanks. Our eye goes first, of course, to the figures, which are expertly drawn and almost sculptural in their palpability.

Assael begins painting on a red-orange ground that automatically provides intensity, which is then amplified by his use of relatively pure colors applied with lively brushwork that would get muddled in less gifted hands. He is particularly admired for a heightened sensitivity to light and shadow: the figures are modeled to a great extent through the interaction of warm and cool light, which makes more sense when we remember that light is changing through all the hours he works with his models. Whether its source is obvious or mysterious, the light helps integrate the figure with its setting, allowing Assael to provide contrasts of transparency and opacity that, again, keep our eye interested.

So, with all this skill, what does Assael have to tell us? Fortunately, he addresses the big issues — existential, universal themes like life, death, sleep, and transformation — in oblique, sometimes offbeat, ways that don’t feel like re-animations of earlier explorations of the same terrain. To be sure, there are objects (like tarot cards) and textiles (Superman costumes) that portend, and there are archetypes (like brides) that recur, yet Assael’s scenes do not offer specific stories or pointed morals. Rather, they are riddles that can be unpacked, or simply marveled at. When asked, the artist can explain his intentions eloquently, and when he does, we discern gentle melancholy tinged with subtle wit. Yet even without learning exactly what that monkey symbolizes or how that crowded subway car represents our collective journey through life, we can readily intuit something profound going on here. The images demand that we pause and ponder, which in these rush-rush times is rare and welcome.

Exactly two decades ago, Assael observed that “modernism has taken a direction toward the North Pole — with nowhere to go, frozen. On the way back, we are discovering new territory, using the past as a means of expressing the present. To go forward we must, at times, take a step back and evaluate our position. With progression there is always a [positive, studied] regression.” His words were stunningly prescient; now postmodernism has also left the public behind, and Assael must be gratified that thousands of younger artists are familiar with his work and have trained, or are training, in the techniques he uses.

As for stepping back, it is not only technical skills that are being reclaimed. Assael is a key example of how an original artist utilizes a deep knowledge of art history, not to regurgitate it, but to draw from it what his own vision requires. Not surprisingly, numerous commentators have noted Assael’s debt to Velázquez, Rembrandt, Goya, and Eakins, particularly in his “warts and all” portrayals of real people and his atmospheric lighting. I also see shades of the mid-20th-century American surrealists George Tooker and Jared French, not so much in technique (they drew from the Renaissance), but in terms of patently modern people deftly arranged in enigmatic, vaguely unnerving environments. It’s also clear that Assael is well versed in mythology, legend, the Bible, and religious history. Though he does not illustrate, the archetypes he revisits are redolent of such forerunners as Narcissus or Mary Magdalene.

The blend of naturalist figuration and symbolist spirit Assael has concocted is both unique and invigorating. Long may it flourish.

Article reprinted with permission from Fine Art Connoisseur magazine

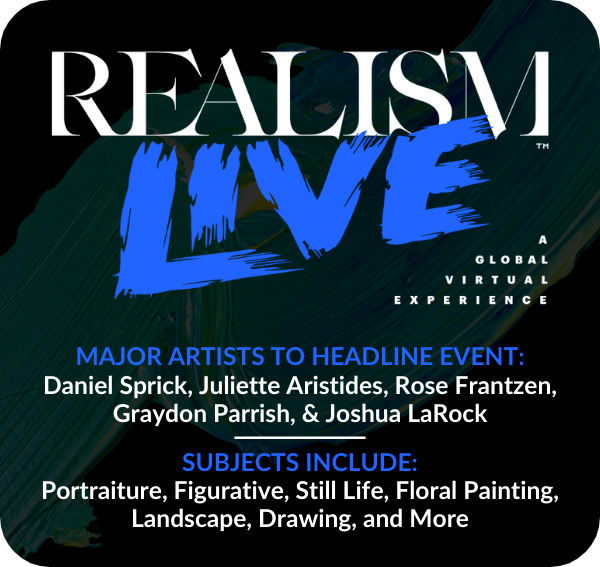

Register for Realism Live, a global virtual art conference, October 2020: