The current tide of quality representational art brings with it the challenge of a very competitive market. How can one’s work gain any notoriety? (Bonus: Includes a mini painting demo!)

Standing Out

BY TJ CUNNINGHAM

From my vantage point I see the resurgence of representational art in America gaining more and more momentum. Every time I look through an art magazine I discover ten more really strong painters. The representational masters living and dead have followings in the tens of thousands and their collectors spend millions of dollars annually.

This tide of quality brings with it the challenge of a very competitive market. How will my work gain any notoriety? Intentionally distorting horizon lines or dripping paint on canvases at random perhaps? I am convinced that fanatically painting from life will eventually give my work the virtuosity to stand out among the thousands of good paintings on the market.

Richard Schmid, David Leffel, Everett Raymond Kinstler and every other great painter of our day insist that painting from life is the best way for the art student to learn how to see and paint well. So I am not trying to offer any new information, but I do have a couple of observations that have made all the difference in my own work. Hopefully, I can convince you to take the advice of the masters.

In my opinion good representational art hangs on good drawing. If my drawing looks wrong, adding pretty colors or jazzy contrast will not save my piece from mediocrity. I learned to draw by copying printed photographs with graphite pencils, but I found the transition to painting from life difficult. Here’s why: Your job as an artist is to take three-dimensional objects and reconstruct them on a flat surface. A photograph meets you halfway by portraying a three-dimensional world, neatly frozen in little flat shapes. Naturally, learning by way of this shortcut makes the transition to drawing from life a challenge.

Learn to draw from life and you will be starting in the right place.

I enjoy reviewing the evolution of my colors because I feel that things have changed for the better. Some of those earlier colors seem so contrived and unnatural to me now. Painting from life sharpens my eye to sensitively see actual color temperature, so it’s not that my paintings have grown more colorful, just more accurate in temperature. This sensitivity in vision seemed to come suddenly, as if one day all of the color around me became so obvious and beautiful. But it’s not magic—hundreds of hours spent painting from life have sharpened and will continue to sharpen my sense of sight.

When you learn to paint from a photograph you are learning from frozen light. Again, through my own study I have come to see light like water—it flows. When I am analyzing my subject I see the light as moving, striking here, splashing there, bouncing, trickling, and gently flowing. This makes understanding values and edges much easier and more interesting! Bounce light or reflected light, for example, will never look right in relation to direct light in a photograph because the camera will represent either too much light or too little. Only by painting from life and looking at the movement of light as it is happening will you capture an authentic look of light in your paintings.

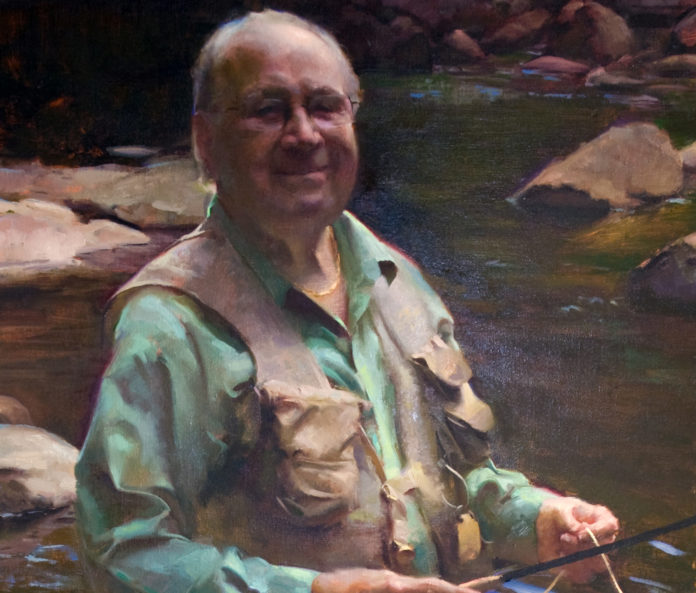

Now, the reasons I’ve given for painting from life apply to students and to the lifetime study of the professional artist, but what about the times when I must paint from photographs? Often portrait commissions require me to work entirely from photo sources. The reasons are obvious—busy schedules, fidgety children, and lack of stamina make a photo shoot more appealing to a client than multi-day painting sessions. Painting large landscapes from life is also very difficult, especially in remote locations.

Here are a few rules I made for myself that help keep my work strong and growing:

1. At least one head study a week completed from life.

2. Make sure your piece of art stands alone—strong apart from the photograph. Don’t copy.

3. Never trust a photograph. Be suspicious of everything it tells you!

Let me unpack my rules. I paint at least one head study a week. This helps me interpret my photographs because my knowledge of how light plays across a face and the dimensionality of human form remains fresh in my mind. Also, I usually work primarily from black and white photos so that I am basing my colors on acquired knowledge.

Most importantly, never let your painting become married to a photograph. I have seen so many figurative paintings and portraits that were clearly copied from a photograph with all of the distortions and gross color, carefully rendered. Some of my old portraits look like that. I find that a wary approach to a photograph along with regular life-study yields strong portraiture and figurative work.

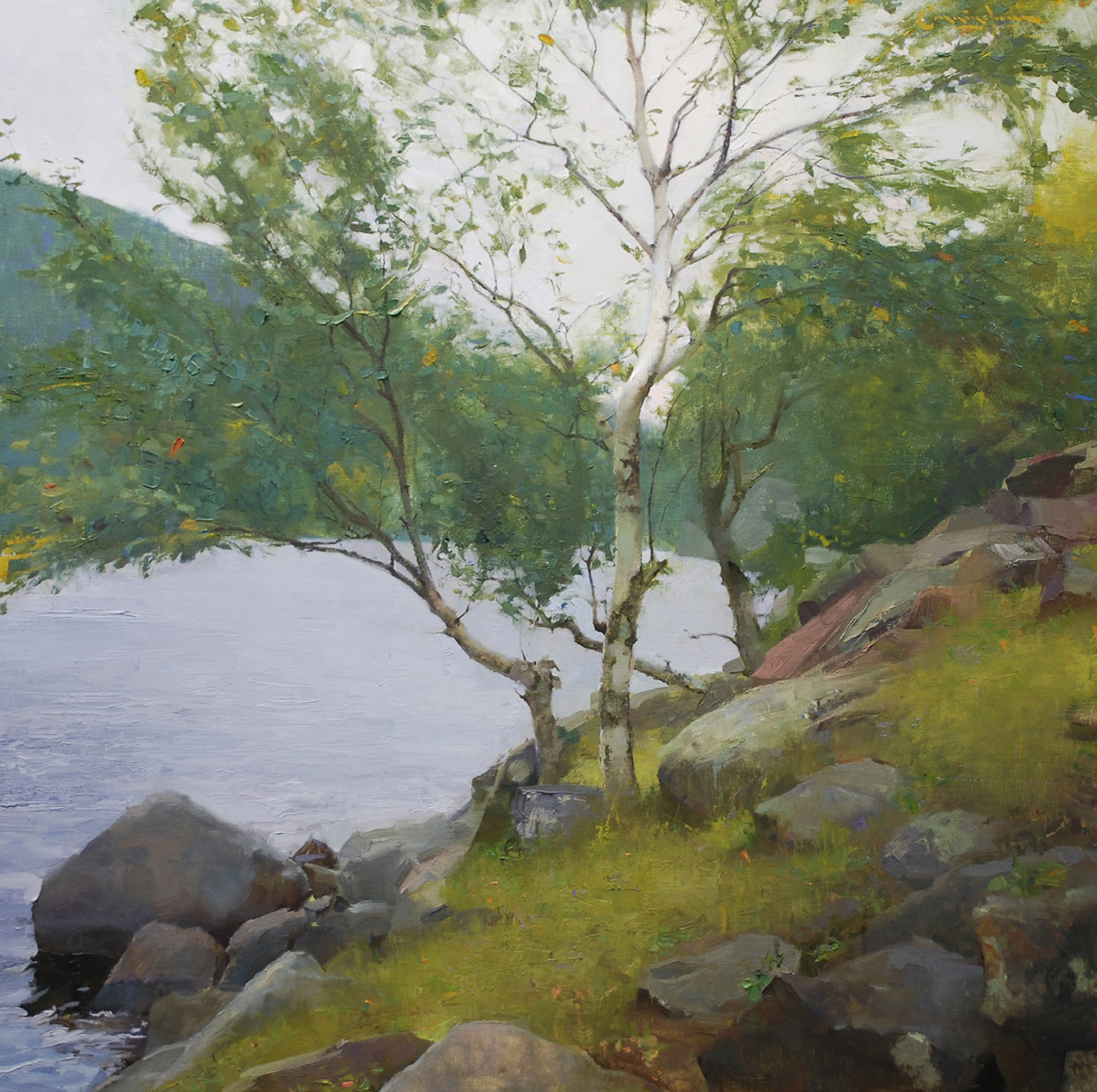

I love painting large landscapes! But carrying a 36 x 48 inch canvas into the mountains does not seem feasible. So, of course, I paint many backpack-sized studies from life, bring them back to my studio, and use them as the basis for my larger paintings—simple, right? Edgar Payne and every other great American landscape artist since him used this process.

However, I have found it tremendously tempting to second guess my rough little studies and primarily use photographs to finish my larger landscapes. Here is my landscape painting rule: Always ground your larger paintings entirely on your studies and memories. You will likely find that you don’t need your photographs at all. But if you do, don’t touch a photograph until you have gone just as far as possible with life studies. Always trust your own eyes and brain over a camera’s lens and buffer.

Now, for the real reason I think painting from life is so vital in the making of great art. I often wonder at the paintings that remain compelling in spite of obvious technical flaws. May I say it? I am moved by Van Gogh’s “Starry Night,” though certainly not because of his draftsmanship. To me, a painting’s true strength comes from the experiences that inspired it, not its technical process.

For instance in my own work I see portraiture almost like dating. Think of it—a deep desire to understand and learn as much as possible, but with tremendous admiration that hesitates to see any flaws. You could never get any of that from a photo, or at least I couldn’t. I believe the empathy that I feel meeting with and painting my clients is what gives my portraits their strength. In landscape painting, either the scene reminds me of childhood and home or it gives me the chills of an adventure.

Great paintings are skillfully crafted portrayals of human emotion provoked and perfected by painting from life.

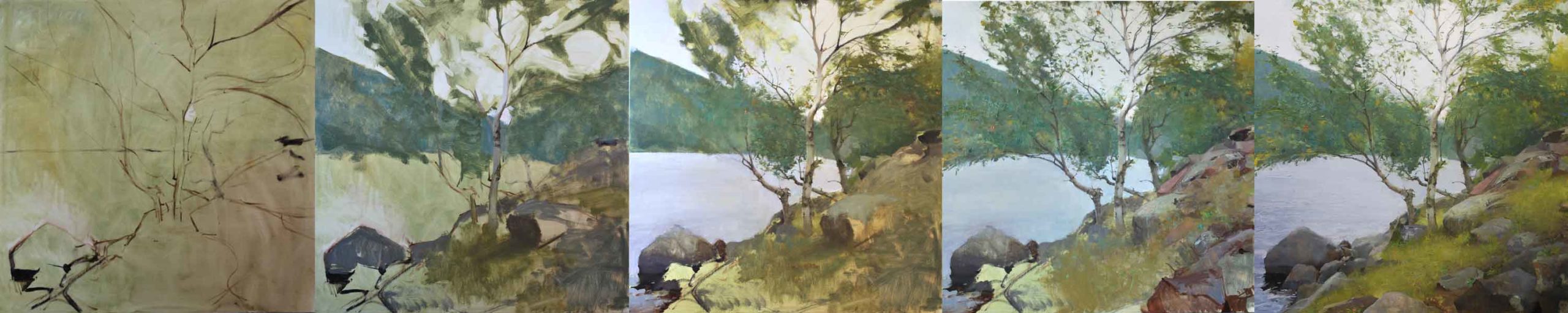

Representational Art Demo: Process for the Painting “Birch”

1. Tone and Design. In the first stage of my painting I toned the canvas with a warm neutral wash and established my design and placement with sweeping brush lines. I need to be careful not to lose this graceful design in subsequent stages. I also confirm my lightest light and darkest dark.

2. Block-in. As I block in my painting, I am careful to establish my value pattern as I establish my basic colors.

3. Island hopping. I work through my painting by looking for the easiest things to paint. If I find an area particularly difficult I temporarily abandon it and paint another section. This means that I have more information and structure to base the difficult parts, which are quite manageable when all the easy parts around them are painted.

4. Final stages. Notice how my painting has maintained the eye flow established in my initial lines? Now all that I need to do is finish the painting!

Learn more about TJ Cunningham at: www.cunninghamfineart.com.

Browse RealismToday.com for more inspiring and educational articles.

Visit EricRhoads.com (Publisher of Realism Today) to learn about opportunities for artists and art collectors, including:

- Art retreats

- International art trips

- Art conventions

- Art workshops (in person and online)

- And more!