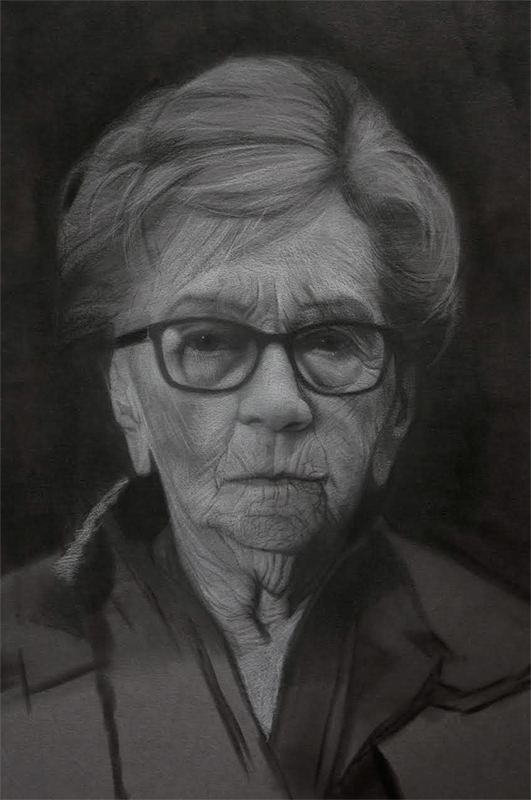

On portrait painting > “The paintings I strive to create are about more than the atrocities they witnessed and were subjected to. These paintings aim to celebrate the fashion designer, the wife, mother, father, grandfather, tailor . . . stories of overcoming their past despite the odds against them.”

By David Kassan

www.davidkassan.com

“Please have a cookie,” Roslyn says with a Polish accent. “Thanks!” I say as I reach for the plate.

Roslyn is a sweet older woman whose privacy I feel like I’m invading while scouting out her home for the best place to set up lights and camera equipment. We came into this interview cold with only a faint hint of Rosalyn’s story. Chloe, my videographer, and I set up the lights and video equipment around Roslyn’s kitchen table. As we mic up Roslyn and her sister, we turn on the camera and settle in for a conversation about their lives and experience during the Shoah.

Roslyn: “We are twins. My name before the war was Roslyn Sharf, S-H-A-R F. So, when the war broke out in 1939, we were still living in our house. Later, about a year or a year-and-a-half later, they told us to leave the house. So, a neighbor gave us a place to live for about five months, and then it wasn’t good anymore. We went into hiding to another neighbor, for a month, in an attic.”

Me: “Who was the neighbor?”

Roslyn: “The neighbor Poles, Polish.”

Bella: “They were . . .”

Roslyn: “. . . they were Witnesses of . . .”

Bella: “Jehovah’s Witnesses.”

Roslyn: “Jehovah’s Witnesses. They believed that a person should be helped. And they were poor, and hadn’t enough food, and then . . . And Mother helped them, I presume,when they were so poor, when they came to the store, she gave them things for nothing. I mean, they bought it, but without money, and then they didn’t pay. So, they felt obligated, grateful, and they let us stay a month.”

“Then mother decided it’s not good enough, and she took us to the station. We walked maybe three hours. On the train she started to talk to the Poles. Our Polish was very good, clean of Jewish intonation, and she asked where they are going. So, they said that they’re going to Warsaw, and Mother said we are chased out Polish people from a different area, and she’s looking for a job.”

“As we approached Warsaw, the woman said to us, ‘Come on. I know somebody in the building who wants a housekeeper. They need people.’ So, she gave us the addresses. Mother got the job.”

Bella and Roslyn are both Survivors of the Shoah. They live a few floors apart from each other in a high rise building in Queens, NYC. They are fraternal twins. During the Nazi occupation of Poland their family had to go into hiding. They were 12 years old and both had blonde hair and blue eyes so they were able to hide in plain sight. Their mother moved them to a town where nobody knew them, and they were split up to go into hiding with two separate families.

After our conversation, Chloe and I get the usual questions asking us who we are. Are you married? Do you have kids? I tell them that I have a beautiful fiancée named Shana, and receive the same response back, “Oh! Shana, Beautiful.” Shana means Beautiful in Yiddish. Shana madala. I always think that Shana’s mom named her perfectly, but I’m biased.

I feel very privileged to be here, listening to these heartfelt, sometimes horrific and sad stories that somehow always end up being inspiring.

In 1917, a young Murray Kassan immigrated to the United States, escaping ethnic cleansing on the border of the Ukraine and Romania by the Cossacks. Murray was my grandfather, and his story of survival is a vague unfocused legend in my family for many reasons. When my father was fifteen years old, Murray was estranged from the family, and my father never saw him again. He passed away when I was very little and I never got to meet him. His story of survival is now only fragmented stories.

Painting for me is my way of understanding the world around me, my way of connecting, and my excuse to interact and learn. This has been my personal way of connecting to my grandfather’s lost story. With every survivor’s story I hear and record into a painting, I feel I move closer to the connection with my grandfather that I never had.

There are fewer than 150,000 Holocaust Survivors worldwide and their stories of survival include everything after the Shoah, but their numbers are quickly dwindling. The paintings I strive to create are about more than the atrocities they witnessed and were subjected to. These paintings aim to celebrate the fashion designer, the wife, mother, father, grandfather, tailor . . . stories of overcoming their past despite the odds against them.

I never thought my personal painting journey would lead to becoming a documentarian. However, now that I think about it, it is the natural progression of the rules I established for my work and the philosophy of what I want for my work. What surprises me most is the way these paintings have changed me as a person, and how I see the world.

This whole project started with a commission inquiry. For the past 10 years, I have been focused on my own personal work and have avoided painting commissions altogether, favoring creative freedom instead of financial windfall. All of the commissions I had done previously had me compromising my truest artistic values.

Back in 2014, I was asked by an Israeli collector if I could do a commission for him. While I was in the process of politely declining, he said that he understood, but that his subject was a very special woman; she was a survivor of the Shoah.

I immediately said that I would paint her, not as a commission though, but as a painting that I could have control over, and that they would have the option to collect the painting if they wanted. If not I would exhibit the painting at the gallery that represents my work. The collector went back to his mother-in-law. She had a look at my work and politely declined. My interest in painting this subject had been sparked and I have set out on this journey to paint and film as many of these very special individuals as I can.

The beginnings of my journey have been very humble. I have met almost all of my survivors through word of mouth. Early on, I was limited to survivors who lived close to me in the New York and New Jersey area, since the project has been a grassroots initiative and was self-funded in terms of travel, videography, and editing costs. That is slowly changing through the use of social media and, again, word of mouth. I have been helped along by some amazing individuals as well as by some organizations that have been generously helping me get from place to place so that we could meet new groups of survivors, as well as helping me with material and studio costs.

Related Article > Striving for Truth and Beauty in Art

Up until this point, I have been painting single and double figure paintings. In this series, as well as my previous work, I’ve always made my figures life sized so that they can speak to the viewer. The reason for this is because it allows a one-to-one conversation between the subject and the viewer, an intimate connection without my presence through loud brush-strokes or ego getting in the way.

Doing these manageable paintings for myself has been a great way of slowly evolving my work into a more meaningful head space for myself. After about three years of slowly establishing myself with this evolution of work, I had the thought that I wanted to both challenge myself as well as create a painting that is much more involved and larger — a work that would be indelible, a painting with weight.

Through a lucky connection from Facebook, I was put in touch with Elana Samuels, a woman who coordinates the survivors who speak to the public at the Museum of Tolerance in Los Angeles. She said that she could put together a group of Survivors of Auschwitz to meet with me if I could get out to LA.

When I first conceived the idea of a larger painting I was thinking it would be of maybe five survivors, and I didn’t know how to group them. The survivors needed a connection to one another. For example, in the past pieces I have painted married couples, and in the case of Bella and Roslyn, twin sisters. Elana came up with the idea of grouping together survivors of Auschwitz since they have different experiences but also some shared. They also represent the many different countries that were imprisoned. My original idea of five or six survivors was greatly expanded when Elana got back to me with the news that she could have twelve survivors meet up with me at the museum to photograph and interview.

Luckily, I received a grant from the Jerry Goldstein Foundation — named after the founder of Jerry’s Artarama — that covered our travel costs to interview the group in Los Angeles. Having a company really believe in the project and in my work was a huge lift! I was determined to really get as much out of the trip as possible!

While we were there we met with eleven survivors for the large painting, along with another three survivors for standalone paintings. Unfortunately, one of the original twelve couldn’t make it due to health issues, which really highlighted the inherent urgency in the project. I was able to do a benefit drawing demo at the Safe House Atelier where I drew Joshua Kaufman, a Survivor who lives in Los Angeles, to also help with the costs of the trip.

Also, while we were in LA a very good friend and painting mentor of mine, John Nava, set up an amazing lunch meeting for us with the Director/Curator of the Fisher Museum of Art and the Director of the USC Shoah Foundation. They both agreed to help out with the painting series, and also wanted to talk about creating an exhibition for the paintings at the USC Fisher Museum of Art in the Spring of 2019.

Since then I developing the Eleven Survivors of Auschwitz painting, through digital paintings and sketches. It is be 18 feet by 8 feet high and consist of five acrylic mirror panels pulled together. The process has been exciting and the logistics are much more involved than I thought they would be. I’ve been documenting the challenges, stories, progress and the entire process on patreon.com/davidkassan, to create a community around this series of paintings and each Survivor’s story.

My approach to the work I create is more conceptional and is based on my intention first. I try not to think of my work as having a style; it just is what it is. Oil paint, like skin, is translucent, so it’s the perfect medium for capturing humanity. I want painting surfaces that are layered with the history of its making, mimicking the experience that our skin receives as our barrier to the world.

There is so much trial and error in my work, and each portrait painting is the record of successes and failures, hundreds of layers of brushstrokes. My paintings are the culmination of all of these thoughts — my attempts at a deeper understanding through the subtlety of the answers to my questions about each individual I paint. These objective answers, correct or not, really help me to develop a clearer representation of the lives each survivor has lived. I am there just as a conduit to listen with my brush and to document in an intensely honest way.

Early on in my painting life, I struggled very hard to make work I thought would be salable, just so I could make a living to paint another painting. About eight years ago I started to find that the work, though salable, wasn’t nourishing. I turned inward to subjects that were close to me by painting my family and people in my life.

With the paintings I’ve completed of the survivors, I feel that I have a responsibility to not only represent them in the most authentic possible way, but also to document a deeper understanding of their lives and not just the horrors of what they witnessed early in their lives. My goal is to capture their resilience throughout their lives. This goal is a tall order for a painter. I try to never put deadlines on the paintings, and I work on them until they have to leave the studio. Each story for me is almost sacred, like I am painting a nonfiction novel about each person. Now I am fortunate to be able to create paintings that are rewarding in how they educate and affect people outside of myself.