Find inspiration in the following excerpt on classical drawing from Robert Johnson’s timeless book, “On Becoming a Painter.”

The Classical Drawing Tradition

By Robert A. Johnson

Drawing is the foundation upon which all enduring art in the Western classical tradition rests. It has been said that if one wishes to push through and discover the core – the wellspring – of all good art, one would find the line of a life drawing. For centuries a fundamental knowledge and skill in draftsmanship was a prerequisite to the honor of picking up a paintbrush.

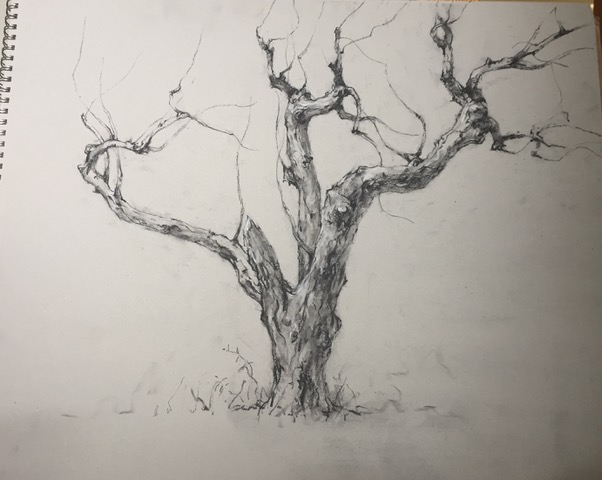

Why is drawing so important? Partly because one learns to free oneself from psychological baggage that causes one to focus on objects instead of shapes and masses, light and shadow.

At its core, the process of learning to draw trains the eye to recognize relationships in a methodical way. Eventually the knowledge gained is stored in our psyche and flows out automatically, as smoothly and unconsciously as an athlete performing at the top of his game. The skill and habit of observing relationships is carried over when you put down the pencil and pick up the brush.

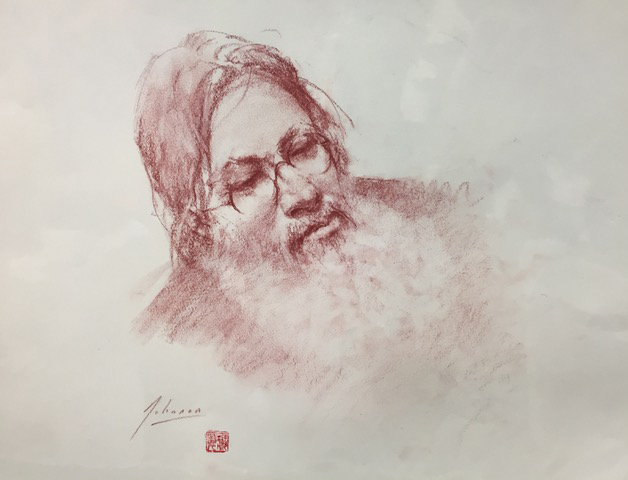

You must draw with humility and detachment. Humility means always letting nature take the lead. Detachment is the ability to let go of your ego and simply give yourself over to drawing; to observe the world with complete honesty. You must be willing to make mistakes, and you must refuse to fall in love with your own work.

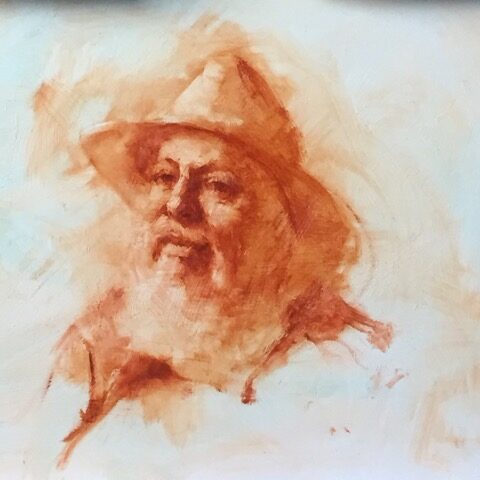

In the classical tradition, the human figure is the supreme subject. It was thought – with good reason – that if a student could master the human form, in its almost infinite complexity, he could master anything. At the Ecole des Beaux-Arts in nineteenth-century Paris, students spent months or even years drawing from plaster casts of antique statues before being permitted to draw from live models.

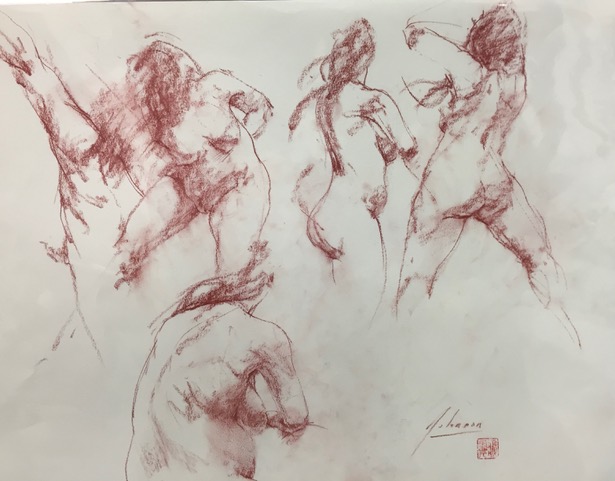

Short poses, often called gesture drawings, are good for training your observational skill and developing the habit of detachment. The model assumes a pose for one to three minutes, which forces the artist to distill the essence of the gesture into a few quick lines. The goal is to detach the ego from the process – to learn to draw without thinking.

There is an interesting paradox about drawing short poses: although they demand close concentration to be convincing, they are often the most vibrant drawings produced by novice artists. In the gesture drawing, a subtle and fascinating transition takes place between raw technique and the spiritual essence of the subject. With enough gesture drawings, the process becomes automatic. The creative process is free to break loose, and the hand of the artist achieves the grace and flow that comes with being perfectly at ease.

Artist Standards

Because we no longer have Ecole des Beaux-Arts (or anything like it) to set standards for teaching drawing, it is of foremost importance that you take great care in setting your own standards.

If you are lucky, you may find a class with one of the few teachers trained in the classical tradition, or you may find yourself in a community of artists who aspire to high goals. Ultimately, though, we are all on our own. My personal standard was suggested by my brother Ben, who was unwavering in his faith in the Old Masters as the ultimate standard of excellence. This is the standard to which I aspire.

Although none of us can know if our work will ever equal that of a Rembrandt, we shouldn’t think that it is an impossibility either. Like the Old Masters, we all start from a blank piece of paper. Having an exalted standard keeps us from succumbing to self-satisfaction at a lower level than we are truly capable of.

Helpful Links

- Art video workshops by Robert Johnson, including the book this article is excerpted from, “On Becoming a Painter”

- Robert Johnson’s website

- Related Article: Fresh Color: On Painting with Oil