Those of us who choose realism in painting walk a fine line between accepted symbolism and personal vision. It helps to understand the limitations of how we perceive and interpret the world around us.

by Carolyn Anderson

Several deer grazed their way past the house this morning. I was reminded of my friend Sheila Reiman, an artist known for her colorful pastels and oils, and her many deer paintings. Sheila had an ability to see and emphasize color as only a true colorist can. One of her favorite stories involved a couple discussing one of her paintings at an art show in Texas. The woman complained that she had never seen pink deer before. The husband patiently explained that the pink was the quality of light just before the sun went down. Still, the woman persisted. She had never seen pink deer. The husband, frustrated, finally replied, “Yes, but don’t you wish you had?”

Those of us who choose realism in painting walk a fine line between accepted symbolism and personal vision. Unlike a camera, which records all information within its field of view into a two-dimensional format, our vision is far more complicated. We experience space and depth differently; we only see detail wherever we direct our central vision; and what we see can be compromised by what we expect to see. We interpret the incoming signals into a stable and coherent image, but the downside is that the process of interpretation is subject to often simple interpretations of complex and ever-changing information.

Children learn to recognize and create two-dimensional images representing the visual world. The symbols created are oversimplified in representation – grass is green, the sky is blue, the sun is yellow, and apples are red. The symbols are generic, two-dimensional, and lack edge variation suggesting three-dimensional reality. We, in turn, see the “thing” or the symbol for the thing, a condensed version of visual reality. Our ability to accurately quantify what we are seeing is compromised by the shortcuts we have learned. We learn to see what we know, and the knowing often gets in the way of the seeing.

We see a red apple, for example, as always red and always “apple-shaped,” not noticing the nuance of color, shape, and the variety of edges that are part of three-dimensional reality. We see ourselves as life-size when looking in a mirror, but a quick measurement will prove the image in the mirror is closer to only one-half actual size. We see what we know and what we expect to see.

Painting a still life, for example, requires being able to take the information out of the context of naming objects and seeing the visual relationships as a whole, each part defined by the other. No longer is it an apple and orange, for example, but a “still life” – a new and different entity. Only then can we actually look for and learn to see the visual information that truly describes the reality of the still life. We need to be able to see the quality of light, the color of shadows, the repetition of patterns, and where information is lost and where it is found. We need to look beyond the idea of local color until we truly understand and see the possibilities of color modified by light, shadow, and other colors.

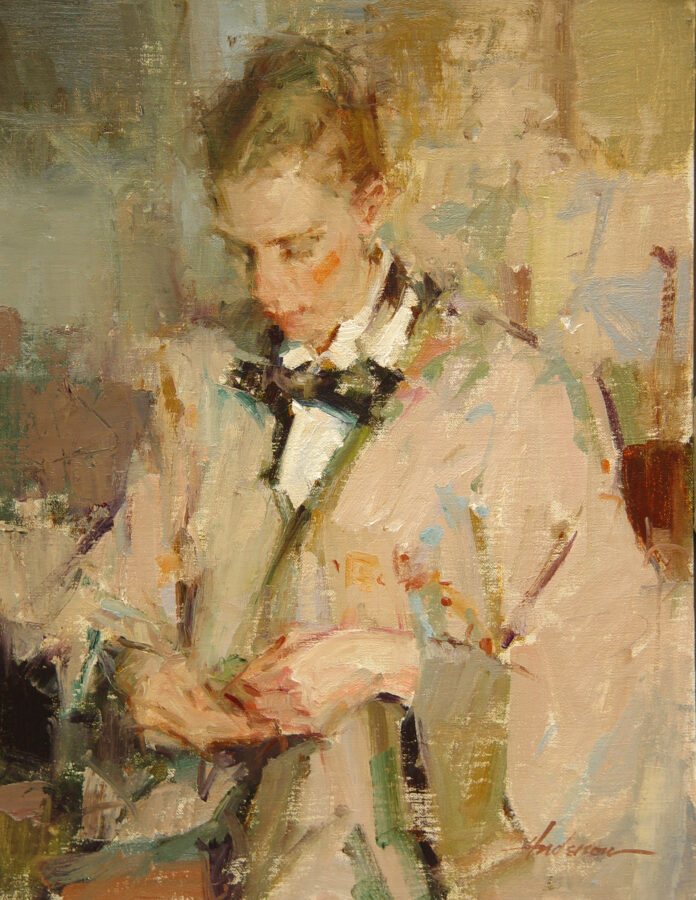

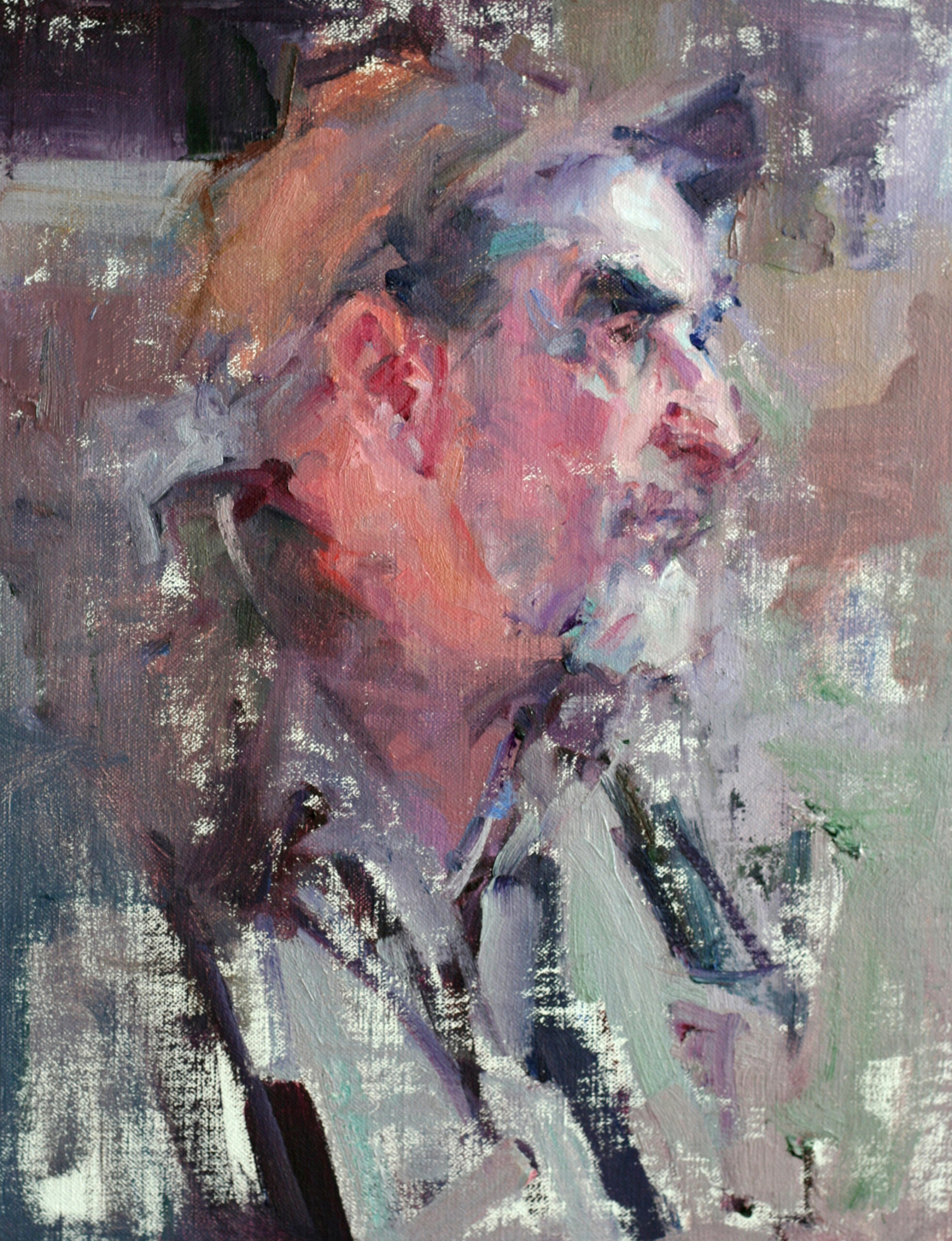

In our quest for realism, we need to look beyond what we think is real and access the visual information that actually describes our reality. We need to question not just how we see, but also what we think we see. Interpreting visual reality should be about exploration and not just an attempt at learned re-creation. The history of art is a progression of images dealing with versions of reality. The Impressionists dealt with issues of light and color, while the Cubists dealt with shapes. Sargent was a master of visual notation and implied reality, while Fechin and other Russian masters explored the power of abstract pattern. Good art is dependent on observation and strong visual elements.

Learning to see and compare visual information becomes a process of growth and exploration. A drawing of a tree done by a child is not that far removed from a painting of a tree done by an adult. They both use symbolism to represent reality. The difference lies in the complexity of the visual language and the ability of the artist to perceive nuance and variation and to organize and edit that wealth of information into a personal expression.

The basic elements of visual language, line, shape, value, and color are unlimited in their possibilities. They are not just tools of craft, but also creativity. When we accept how limiting our dependence on symbols can become and understand how our verbal language stymies the possibilities of visual experience, we can begin to learn to see beyond the obvious. Art is not reality – it is a perception of an artist’s reality. Art, really, is all about seeing.

Connect with Carolyn Anderson at www.carolynanderson.com.

- Become a Realism Today Ambassador for the chance to see your work featured in our newsletter, on our social media, and on this site.